21.1: Nuclear Structure and Stability

- Page ID

- 38339

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Describe nuclear structure in terms of protons, neutrons, and electrons

- Calculate mass defect and binding energy for nuclei

- Explain trends in the relative stability of nuclei

Nuclear chemistry is the study of reactions that involve changes in nuclear structure. The chapter on atoms, molecules, and ions introduced the basic idea of nuclear structure, that the nucleus of an atom is composed of protons and, with the exception of \(\ce{^1_1H}\), neutrons. Recall that the number of protons in the nucleus is called the atomic number (\(Z\)) of the element, and the sum of the number of protons and the number of neutrons is the mass number (\(A\)). Atoms with the same atomic number but different mass numbers are isotopes of the same element. When referring to a single type of nucleus, we often use the term nuclide and identify it by the notation:

\[\ce{^{A}_{Z}X} \label{Eq1} \]

where

- \(X\) is the symbol for the element,

- \(A\) is the mass number, and

- \(Z\) is the atomic number.

Often a nuclide is referenced by the name of the element followed by a hyphen and the mass number. For example, \(\ce{^{14}_6C}\) is called “carbon-14.”

Protons and neutrons, collectively called nucleons, are packed together tightly in a nucleus. With a radius of about 10−15 meters, a nucleus is quite small compared to the radius of the entire atom, which is about 10−10 meters. Nuclei are extremely dense compared to bulk matter, averaging \(1.8 \times 10^{14}\) grams per cubic centimeter. For example, water has a density of 1 gram per cubic centimeter, and iridium, one of the densest elements known, has a density of 22.6 g/cm3. If the earth’s density were equal to the average nuclear density, the earth’s radius would be only about 200 meters (earth’s actual radius is approximately \(6.4 \times 10^6\) meters, 30,000 times larger). Example \(\PageIndex{1}\) demonstrates just how great nuclear densities can be in the natural world.

Density of a Neutron Star Neutron stars form when the core of a very massive star undergoes gravitational collapse, causing the star’s outer layers to explode in a supernova. Composed almost completely of neutrons, they are the densest-known stars in the universe, with densities comparable to the average density of an atomic nucleus. A neutron star in a faraway galaxy has a mass equal to 2.4 solar masses (1 solar mass = \(M_☉\) = mass of the sun = \(\mathrm{1.99 \times 10^{30}\; kg}\)) and a diameter of 26 km.

- What is the density \(\rho\) of this neutron star?

- How does this neutron star’s density compare to the density of a uranium nucleus, which has a diameter of about 15 fm (1 fm = 10–15 m)?

Solution

We can treat both the neutron star and the U-235 nucleus as spheres. Then the density for both is given by:

\[\rho = \dfrac{m}{V} \nonumber \]

with

\[V = \dfrac{4}{3} \pi r^3 \nonumber \]

(a) The radius of the neutron star is \(\mathrm{\dfrac{1}{2}\times 26\; km = \dfrac{1}{2} \times 2.6 \times 10^4\; m = 1.3 \times 10^4\; m}\) so the density of the neutron star is:

\[ \begin{align*} \rho &= \dfrac{m}{V} \\[4pt] &=\dfrac{m}{\frac{4}{3}\pi r^3} \\[4pt] &= \dfrac{2.4(1.99 \times 10^{30}\;kg)}{\frac{4}{3} \pi (1.3 \times 10^4m)^3} \\[4pt] &=5.2 \times 10^{17}\;kg/m^3 \end{align*} \nonumber \]

(b) The radius of the U-235 nucleus is \(\mathrm{\dfrac{1}{2} \times 15 \times 10^{−15}\;m=7.5 \times 10^{−15}\;m}\), so the density of the U-235 nucleus is:

\[ \begin{align*} \rho &=\dfrac{m}{V} \\[4pt] &=\dfrac{m}{\frac{4}{3}\pi r^3} \\[4pt] &= \dfrac{235\;amu \left(\frac{1.66 \times 10^{-27}\;kg}{1\;amu}\right)}{ \frac{4}{3} \pi (7.5 \times 10^{-15}m)^3} \\[4pt] &=2.2 \times 10^{17} \; kg/m^3 \end{align*} \nonumber \]

These values are fairly similar (same order of magnitude), but the nucleus is more than twice as dense as the neutron star.

Find the density of a neutron star with a mass of 1.97 solar masses and a diameter of 13 km, and compare it to the density of a hydrogen nucleus, which has a diameter of 1.75 fm (\(\mathrm{1\; fm = 1 \times 10^{–15}\; m}\)).

- Answer

-

The density of the neutron star is \(\mathrm{3.4 \times 10^{18}\; kg/m^3}\). The density of a hydrogen nucleus is \(\mathrm{6.0 \times 10^{17}\; kg/m^3}\). The neutron star is 5.7 times denser than the hydrogen nucleus.

To hold positively charged protons together in the very small volume of a nucleus requires very strong attractive forces because the positively charged protons repel one another strongly at such short distances. The force of attraction that holds the nucleus together is the strong nuclear force. (The strong force is one of the four fundamental forces that are known to exist. The others are the electromagnetic force, the gravitational force, and the nuclear weak force.) This force acts between protons, between neutrons, and between protons and neutrons. It is very different from the electrostatic force that holds negatively charged electrons around a positively charged nucleus (the attraction between opposite charges). Over distances less than 10−15 meters and within the nucleus, the strong nuclear force is much stronger than electrostatic repulsions between protons; over larger distances and outside the nucleus, it is essentially nonexistent.

Nuclear Binding Energy

As a simple example of the energy associated with the strong nuclear force, consider the helium atom composed of two protons, two neutrons, and two electrons. The total mass of these six subatomic particles may be calculated as:

\[ \underset{\Large\text{protons}}{(2 \times 1.0073\; \text{amu})} + \underset{\Large\text{neutrons}}{(2 \times 1.0087\; \text{amu})} + \underset{\Large\text{electrons}}{(2 \times 0.00055\; \text{amu})}= 4.0331\; \text{amu }\label{Eq2} \]

However, mass spectrometric measurements reveal that the mass of an \(\ce{_2^4 He}\) atom is 4.0026 amu, less than the combined masses of its six constituent subatomic particles. This difference between the calculated and experimentally measured masses is known as the mass defect of the atom. In the case of helium, the mass defect indicates a “loss” in mass of 4.0331 amu – 4.0026 amu = 0.0305 amu. The loss in mass accompanying the formation of an atom from protons, neutrons, and electrons is due to the conversion of that mass into energy that is evolved as the atom forms. The nuclear binding energy is the energy produced when the atoms’ nucleons are bound together; this is also the energy needed to break a nucleus into its constituent protons and neutrons. In comparison to chemical bond energies, nuclear binding energies are vastly greater, as we will learn in this section. Consequently, the energy changes associated with nuclear reactions are vastly greater than are those for chemical reactions.

The conversion between mass and energy is most identifiably represented by the mass-energy equivalence equation as stated by Albert Einstein:

\[E=mc^2 \label{Eq3} \]

where E is energy, m is mass of the matter being converted, and c is the speed of light in a vacuum. This equation can be used to find the amount of energy that results when matter is converted into energy. Using this mass-energy equivalence equation, the nuclear binding energy of a nucleus may be calculated from its mass defect, as demonstrated in Example \(\PageIndex{2}\). A variety of units are commonly used for nuclear binding energies, including electron volts (eV), with 1 eV equaling the amount of energy necessary to the move the charge of an electron across an electric potential difference of 1 volt, making \(\mathrm{1\; eV = 1.602 \times 10^{-19}\; J}\).

Determine the binding energy for the nuclide \(\ce{^4_2 He}\) in:

- joules per mole of nuclei

- joules per nucleus

- MeV per nucleus

Solution

The mass defect for a \(\ce{^4_2He}\) nucleus is 0.0305 amu, as shown previously. Determine the binding energy in joules per nuclide using the mass-energy equivalence equation. To accommodate the requested energy units, the mass defect must be expressed in kilograms (recall that 1 J = 1 kg m2/s2).

(a) First, express the mass defect in g/mol. This is easily done considering the numerical equivalence of atomic mass (amu) and molar mass (g/mol) that results from the definitions of the amu and mole units (refer to the previous discussion in the chapter on atoms, molecules, and ions if needed). The mass defect is therefore 0.0305 g/mol. To accommodate the units of the other terms in the mass-energy equation, the mass must be expressed in kg, since 1 J = 1 kg m2/s2. Converting grams into kilograms yields a mass defect of \(\mathrm{3.05 \times 10^{–5}\; kg/mol}\). Substituting this quantity into the mass-energy equivalence equation yields:

\[\begin{align*} E &=mc^2 \\[4pt] &= \dfrac{3.05 \times 10^{-5}\;kg}{mol} \times \left(\dfrac{2.998 \times 10^8\;m}{s}\right)^2 \\[4pt] &= 2.74×10^{12}\:kg\:m^2s^{-2}mol^{-1} \\[4pt] &=2.74 \times 10^{12}\;J/mol=2.74\: TJ /mol \end{align*} \nonumber \]

(b) The binding energy for a single nucleus is computed from the molar binding energy using Avogadro’s number:

\[\begin{align*} E &= 2.74×10^{12}\:J\:mol^{-1}×\dfrac{1\: mol}{6.022×10^{23}\:nuclei} \\[4pt] &=4.55×10^{-12} \: J =4.55\: pJ \end{align*} \nonumber \]

(c) Recall that \(\mathrm{1\; eV = 1.602 \times 10^{-19}\; J}\). Using the binding energy computed in part (b):

\[\begin{align*} E &= 4.55×10^{-12} \: J× \dfrac{1\: eV}{1.602×10^{-19}\:J} \\[4pt] &=2.84×10^7\:eV=28.4\: MeV \end{align*} \nonumber \]

What is the binding energy for the nuclide\(\ce{^{19}_9F}\) (atomic mass: 18.9984 amu) in MeV per nucleus?

- Answer

-

148.4 MeV

Because the energy changes for breaking and forming bonds are so small compared to the energy changes for breaking or forming nuclei, the changes in mass during all ordinary chemical reactions are virtually undetectable. As described in the chapter on thermochemistry, the most energetic chemical reactions exhibit enthalpies on the order of thousands of kJ/mol, which is equivalent to mass differences in the nanogram range (10–9 g). On the other hand, nuclear binding energies are typically on the order of billions of kJ/mol, corresponding to mass differences in the milligram range (10–3 g).

Nuclear Stability

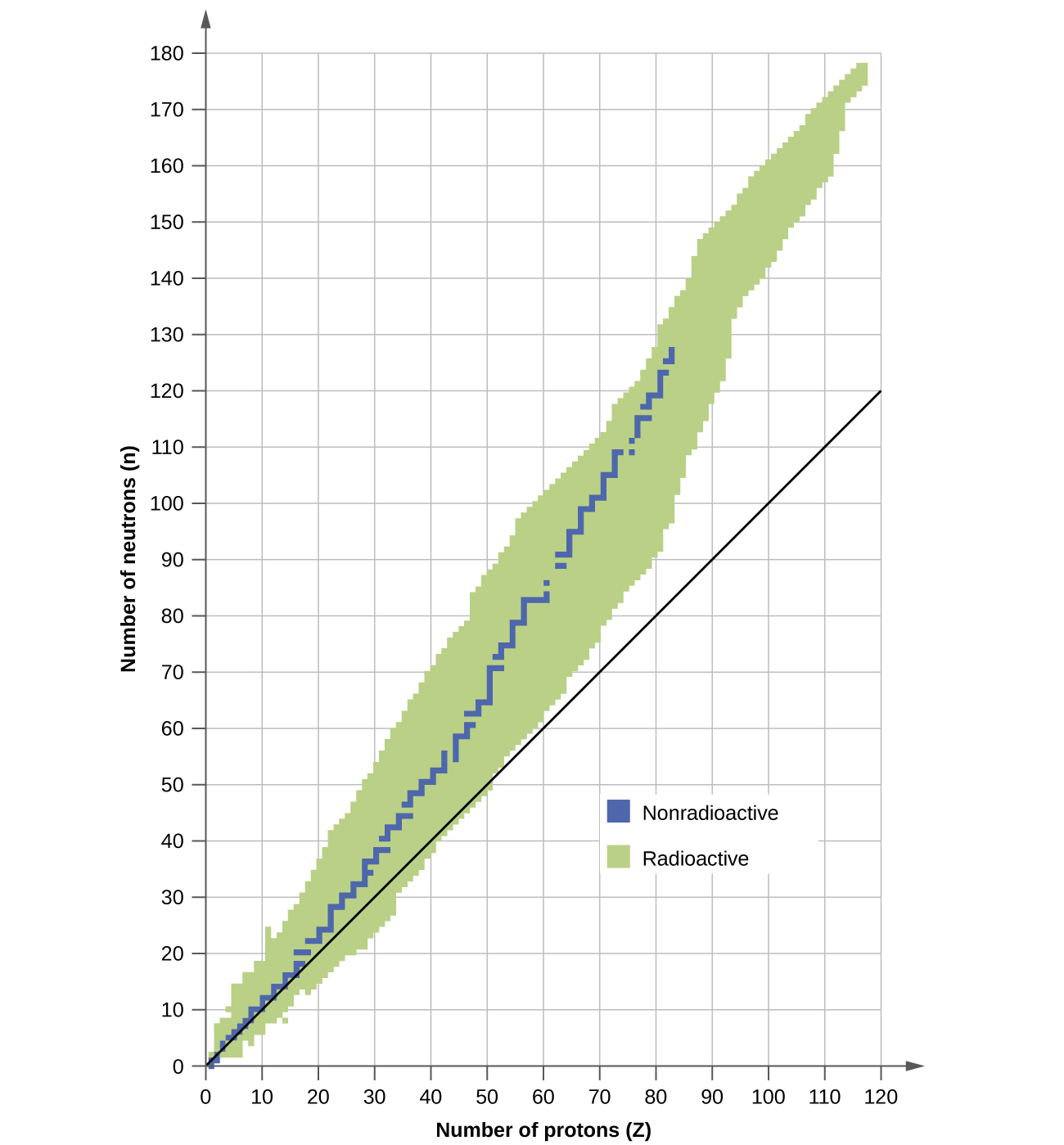

A nucleus is stable if it cannot be transformed into another configuration without adding energy from the outside. Of the thousands of nuclides that exist, about 250 are stable. A plot of the number of neutrons versus the number of protons for stable nuclei reveals that the stable isotopes fall into a narrow band. This region is known as the band of stability (also called the belt, zone, or valley of stability). The straight line in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) represents nuclei that have a 1:1 ratio of protons to neutrons (n:p ratio). Note that the lighter stable nuclei, in general, have equal numbers of protons and neutrons. For example, nitrogen-14 has seven protons and seven neutrons. Heavier stable nuclei, however, have increasingly more neutrons than protons. For example: iron-56 has 30 neutrons and 26 protons, an n:p ratio of 1.15, whereas the stable nuclide lead-207 has 125 neutrons and 82 protons, an n:p ratio equal to 1.52. This is because larger nuclei have more proton-proton repulsions, and require larger numbers of neutrons to provide compensating strong forces to overcome these electrostatic repulsions and hold the nucleus together.

The nuclei that are to the left or to the right of the band of stability are unstable and exhibit radioactivity. They change spontaneously (decay) into other nuclei that are either in, or closer to, the band of stability. These nuclear decay reactions convert one unstable isotope (or radioisotope) into another, more stable, isotope. We will discuss the nature and products of this radioactive decay in subsequent sections of this chapter.

Several observations may be made regarding the relationship between the stability of a nucleus and its structure. Nuclei with even numbers of protons, neutrons, or both are more likely to be stable (Table \(\PageIndex{1}\)). Nuclei with certain numbers of nucleons, known as magic numbers, are stable against nuclear decay. These numbers of protons or neutrons (2, 8, 20, 28, 50, 82, and 126) make complete shells in the nucleus. These are similar in concept to the stable electron shells observed for the noble gases. Nuclei that have magic numbers of both protons and neutrons, such as \(\ce{^4_2He}\), \(\ce{^{16}_8O}\), \(\ce{^{40}_{20}Ca}\), and \(\ce{^{208}_{82}Pb}\) and are particularly stable. These trends in nuclear stability may be rationalized by considering a quantum mechanical model of nuclear energy states analogous to that used to describe electronic states earlier in this textbook. The details of this model are beyond the scope of this chapter.

| Number of Stable Isotopes | Proton Number | Neutron Number |

|---|---|---|

| 157 | even | even |

| 53 | even | odd |

| 50 | odd | even |

| 5 | odd | odd |

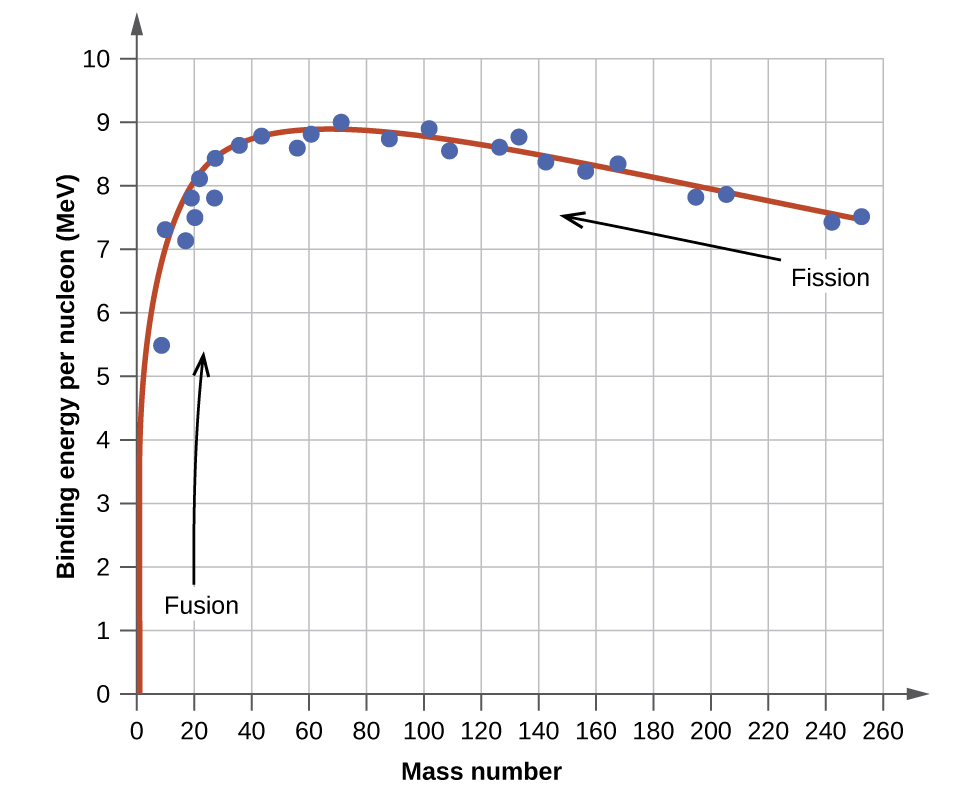

The relative stability of a nucleus is correlated with its binding energy per nucleon, the total binding energy for the nucleus divided by the number or nucleons in the nucleus. For instance, the binding energy for a \(\ce{^4_2He}\) nucleus is therefore:

\[\mathrm{\dfrac{28.4\; MeV}{4\; nucleons}=7.10\; MeV/nucleon} \label{Eq3a} \]

The binding energy per nucleon of a nuclide on the curve shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)

The iron nuclide \(\ce{^{56}_{26}Fe}\) lies near the top of the binding energy curve (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)) and is one of the most stable nuclides. What is the binding energy per nucleon (in MeV) for the nuclide \(\ce{^{56}_{26}Fe}\) (atomic mass of 55.9349 amu)?

Solution

As in Example, we first determine the mass defect of the nuclide, which is the difference between the mass of 26 protons, 30 neutrons, and 26 electrons, and the observed mass of an \(\ce{^{56}_{26}Fe}\) atom:

\[\begin{align*}

\mathrm{Mass\: defect}&=\mathrm{[(26×1.0073\: amu)+(30×1.0087\: amu)+(26×0.00055\: amu)]−55.9349\: amu}\\

&=\mathrm{56.4651\: amu−55.9349\: amu}\\

&=\mathrm{0.5302\: amu}

\end{align*} \nonumber \]

We next calculate the binding energy for one nucleus from the mass defect using the mass-energy equivalence equation:

\[\begin{align*}

E&=mc^2=\mathrm{0.5302\: amu×\dfrac{1.6605×10^{-27}\:kg}{1\: amu}×(2.998×10^8\:m/s)^2}\\

&=\mathrm{7.913×10^{−11}\:\textrm{kg⋅m}/s^2}\\

&=\mathrm{7.913×10^{−11}\:J}

\end{align*} \nonumber \]

We then convert the binding energy in joules per nucleus into units of MeV per nuclide:

\[\mathrm{7.913×10^{−11}\:J×\dfrac{1\: MeV}{1.602×10^{−13}\:J}=493.9\: MeV} \nonumber \]

Finally, we determine the binding energy per nucleon by dividing the total nuclear binding energy by the number of nucleons in the atom:

\[\textrm{Binding energy per nucleon}=\mathrm{\dfrac{493.9\: MeV}{56}=8.820\: MeV/nucleon} \nonumber \]

Note that this is almost 25% larger than the binding energy per nucleon for \(\ce{^4_2He}\).(Note also that this is the same process as in Example \(\PageIndex{2}\, but with the additional step of dividing the total nuclear binding energy by the number of nucleons.)

What is the binding energy per nucleon in \(\ce{^{19}_9F}\) (atomic mass, 18.9984 amu)?

- Answer

-

7.810 MeV/nucleon

Summary

An atomic nucleus consists of protons and neutrons, collectively called nucleons. Although protons repel each other, the nucleus is held tightly together by a short-range, but very strong, force called the strong nuclear force. A nucleus has less mass than the total mass of its constituent nucleons. This “missing” mass is the mass defect, which has been converted into the binding energy that holds the nucleus together according to Einstein’s mass-energy equivalence equation, E = mc2. Of the many nuclides that exist, only a small number are stable. Nuclides with even numbers of protons or neutrons, or those with magic numbers of nucleons, are especially likely to be stable. These stable nuclides occupy a narrow band of stability on a graph of number of protons versus number of neutrons. The binding energy per nucleon is largest for the elements with mass numbers near 56; these are the most stable nuclei.

Key Equations

- E = mc2

Glossary

- band of stability

- (also, belt of stability, zone of stability, or valley of stability) region of graph of number of protons versus number of neutrons containing stable (nonradioactive) nuclides

- binding energy per nucleon

- total binding energy for the nucleus divided by the number of nucleons in the nucleus

- electron volt (eV)

- measurement unit of nuclear binding energies, with 1 eV equaling the amount energy due to the moving an electron across an electric potential difference of 1 volt

- magic number

- nuclei with specific numbers of nucleons that are within the band of stability

- mass defect

- difference between the mass of an atom and the summed mass of its constituent subatomic particles (or the mass “lost” when nucleons are brought together to form a nucleus)

- mass-energy equivalence equation

- Albert Einstein’s relationship showing that mass and energy are equivalent

- nuclear binding energy

- energy lost when an atom’s nucleons are bound together (or the energy needed to break a nucleus into its constituent protons and neutrons)

- nuclear chemistry

- study of the structure of atomic nuclei and processes that change nuclear structure

- nucleon

- collective term for protons and neutrons in a nucleus

- nuclide

- nucleus of a particular isotope

- radioactivity

- phenomenon exhibited by an unstable nucleon that spontaneously undergoes change into a nucleon that is more stable; an unstable nucleon is said to be radioactive

- radioisotope

- isotope that is unstable and undergoes conversion into a different, more stable isotope

- strong nuclear force

- force of attraction between nucleons that holds a nucleus together

Paul Flowers (University of North Carolina - Pembroke), Klaus Theopold (University of Delaware) and Richard Langley (Stephen F. Austin State University) with contributing authors. Textbook content produced by OpenStax College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 license. Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/85abf193-2bd...a7ac8df6@9.110).