3.4: Molarity

- Page ID

- 389554

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Describe the fundamental properties of solutions

- Calculate solution concentrations using molarity

- Perform dilution calculations using the dilution equation

In preceding sections, we focused on the composition of substances: samples of matter that contain only one type of element or compound. However, mixtures—samples of matter containing two or more substances physically combined—are more commonly encountered in nature than are pure substances. Similar to a pure substance, the relative composition of a mixture plays an important role in determining its properties. The relative amount of oxygen in a planet’s atmosphere determines its ability to sustain aerobic life. The relative amounts of iron, carbon, nickel, and other elements in steel (a mixture known as an “alloy”) determine its physical strength and resistance to corrosion. The relative amount of the active ingredient in a medicine determines its effectiveness in achieving the desired pharmacological effect. The relative amount of sugar in a beverage determines its sweetness (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). In this section, we will describe one of the most common ways in which the relative compositions of mixtures may be quantified.

Solutions

We have previously defined solutions as homogeneous mixtures, meaning that the composition of the mixture (and therefore its properties) is uniform throughout its entire volume. Solutions occur frequently in nature and have also been implemented in many forms of manmade technology. We will explore a more thorough treatment of solution properties in the chapter on solutions and colloids, but here we will introduce some of the basic properties of solutions.

The relative amount of a given solution component is known as its concentration. Often, though not always, a solution contains one component with a concentration that is significantly greater than that of all other components. This component is called the solvent and may be viewed as the medium in which the other components are dispersed, or dissolved. Solutions in which water is the solvent are, of course, very common on our planet. A solution in which water is the solvent is called an aqueous solution.

A solute is a component of a solution that is typically present at a much lower concentration than the solvent. Solute concentrations are often described with qualitative terms such as dilute (of relatively low concentration) and concentrated (of relatively high concentration).

Concentrations may be quantitatively assessed using a wide variety of measurement units, each convenient for particular applications. Molarity (M) is a useful concentration unit for many applications in chemistry. Molarity is defined as the number of moles of solute in exactly 1 liter (1 L) of the solution:

\[M=\mathrm{\dfrac{mol\: solute}{L\: solution}} \label{3.4.2} \]

A 355-mL soft drink sample contains 0.133 mol of sucrose (table sugar). What is the molar concentration of sucrose in the beverage?

Solution

Since the molar amount of solute and the volume of solution are both given, the molarity can be calculated using the definition of molarity. Per this definition, the solution volume must be converted from mL to L:

\[\begin{align*} M &=\dfrac{mol\: solute}{L\: solution} \\[4pt] &=\dfrac{0.133\:mol}{355\:mL\times \dfrac{1\:L}{1000\:mL}} \\[4pt] &= 0.375\:M \label{3.4.1} \end{align*} \]

A teaspoon of table sugar contains about 0.01 mol sucrose. What is the molarity of sucrose if a teaspoon of sugar has been dissolved in a cup of tea with a volume of 200 mL?

- Answer

-

0.05 M

How much sugar (mol) is contained in a modest sip (~10 mL) of the soft drink from Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)?

Solution

In this case, we can rearrange the definition of molarity to isolate the quantity sought, moles of sugar. We then substitute the value for molarity that we derived in Example 3.4.2, 0.375 M:

\[M=\mathrm{\dfrac{mol\: solute}{L\: solution}} \label{3.4.3} \]

\[ \begin{align*} \mathrm{mol\: solute} &= \mathrm{ M\times L\: solution} \label{3.4.4} \\[4pt] \mathrm{mol\: solute} &= \mathrm{0.375\:\dfrac{mol\: sugar}{L}\times \left(10\:mL\times \dfrac{1\:L}{1000\:mL}\right)} &= \mathrm{0.004\:mol\: sugar} \label{3.4.5} \end{align*} \]

What volume (mL) of the sweetened tea described in Example \(\PageIndex{1}\) contains the same amount of sugar (mol) as 10 mL of the soft drink in this example?

- Answer

-

80 mL

Distilled white vinegar (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)) is a solution of acetic acid, \(CH_3CO_2H\), in water. A 0.500-L vinegar solution contains 25.2 g of acetic acid. What is the concentration of the acetic acid solution in units of molarity?

Solution

As in previous examples, the definition of molarity is the primary equation used to calculate the quantity sought. In this case, the mass of solute is provided instead of its molar amount, so we must use the solute’s molar mass to obtain the amount of solute in moles:

\[\mathrm{\mathit M=\dfrac{mol\: solute}{L\: solution}=\dfrac{25.2\: g\: \ce{CH3CO2H}\times \dfrac{1\:mol\: \ce{CH3CO2H}}{60.052\: g\: \ce{CH3CO2H}}}{0.500\: L\: solution}=0.839\: \mathit M} \label{3.4.6} \]

\[M=\mathrm{\dfrac{0.839\:mol\: solute}{1.00\:L\: solution}} \nonumber \]

Calculate the molarity of 6.52 g of \(CoCl_2\) (128.9 g/mol) dissolved in an aqueous solution with a total volume of 75.0 mL.

- Answer

-

0.674 M

How many grams of NaCl are contained in 0.250 L of a 5.30-M solution?

Solution

The volume and molarity of the solution are specified, so the amount (mol) of solute is easily computed as demonstrated in Example \(\PageIndex{3}\):

\[M=\mathrm{\dfrac{mol\: solute}{L\: solution}} \label{3.4.9} \]

\[\mathrm{mol\: solute= \mathit M\times L\: solution} \label{3.4.10} \]

\[\mathrm{mol\: solute=5.30\:\dfrac{mol\: NaCl}{L}\times 0.250\:L=1.325\:mol\: NaCl} \label{3.4.11} \]

Finally, this molar amount is used to derive the mass of NaCl:

\[\mathrm{1.325\: mol\: NaCl\times\dfrac{58.44\:g\: NaCl}{mol\: NaCl}=77.4\:g\: NaCl} \label{3.4.12} \]

How many grams of \(CaCl_2\) (110.98 g/mol) are contained in 250.0 mL of a 0.200-M solution of calcium chloride?

- Answer

-

5.55 g \(CaCl_2\)

When performing calculations stepwise, as in Example \(\PageIndex{3}\), it is important to refrain from rounding any intermediate calculation results, which can lead to rounding errors in the final result. In Example \(\PageIndex{4}\), the molar amount of NaCl computed in the first step, 1.325 mol, would be properly rounded to 1.32 mol if it were to be reported; however, although the last digit (5) is not significant, it must be retained as a guard digit in the intermediate calculation. If we had not retained this guard digit, the final calculation for the mass of NaCl would have been 77.1 g, a difference of 0.3 g.

In addition to retaining a guard digit for intermediate calculations, we can also avoid rounding errors by performing computations in a single step (Example \(\PageIndex{5}\)). This eliminates intermediate steps so that only the final result is rounded.

In Example \(\PageIndex{3}\), we found the typical concentration of vinegar to be 0.839 M. What volume of vinegar contains 75.6 g of acetic acid?

Solution

First, use the molar mass to calculate moles of acetic acid from the given mass:

\[\mathrm{g\: solute\times\dfrac{mol\: solute}{g\: solute}=mol\: solute} \label{3.4.13} \]

Then, use the molarity of the solution to calculate the volume of solution containing this molar amount of solute:

\[\mathrm{mol\: solute\times \dfrac{L\: solution}{mol\: solute}=L\: solution} \label{3.4.14} \]

Combining these two steps into one yields:

\[\mathrm{g\: solute\times \dfrac{mol\: solute}{g\: solute}\times \dfrac{L\: solution}{mol\: solute}=L\: solution} \label{3.4.15} \]

\[\mathrm{75.6\:g\:\ce{CH3CO2H}\left(\dfrac{mol\:\ce{CH3CO2H}}{60.05\:g}\right)\left(\dfrac{L\: solution}{0.839\:mol\:\ce{CH3CO2H}}\right)=1.50\:L\: solution} \label{3.4.16} \]

What volume of a 1.50-M KBr solution contains 66.0 g KBr?

- Answer

-

0.370 L

Calculations Involving Molarity (M): https://youtu.be/TVTCvKoSR-Q

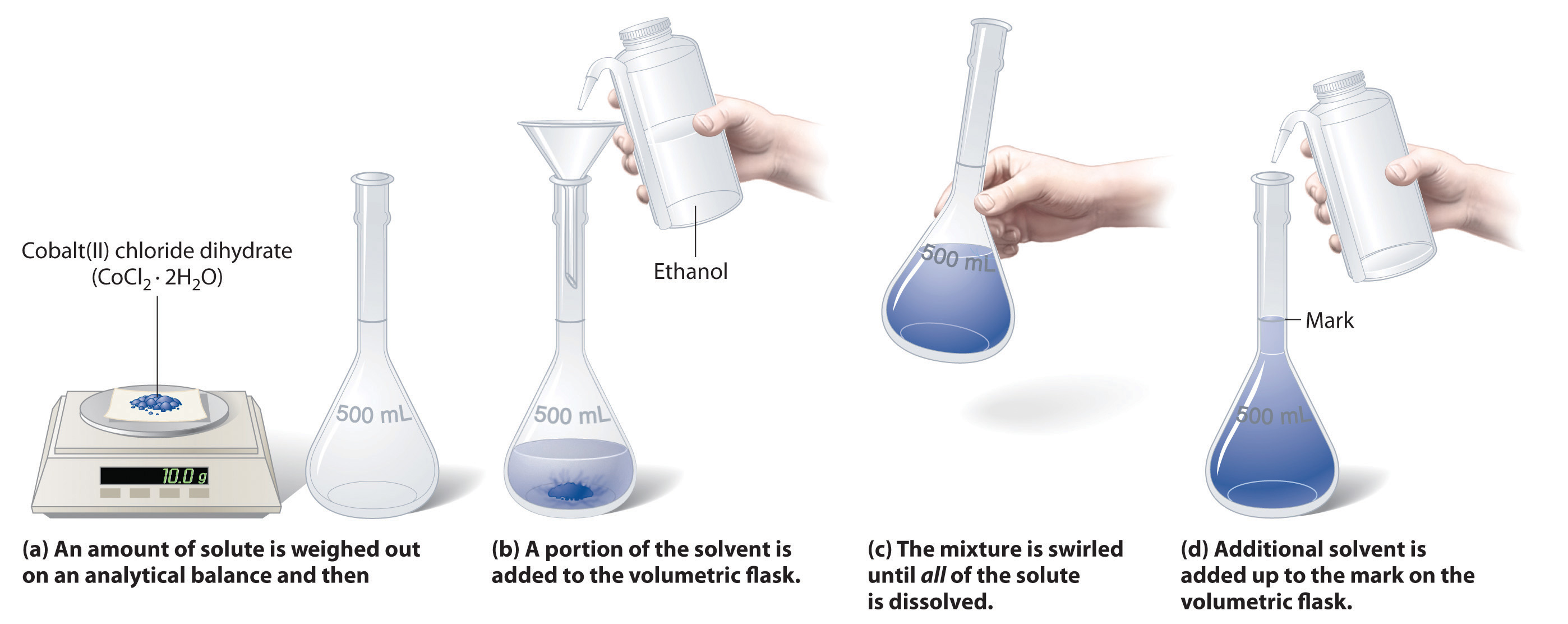

Preparing a Solution With a Solid Solute

A common task in a laboratory is making a solution with with a specific concentration of solute and a specific volume. You start with those two values and can use them to calculate the moles of solute that you need.

\[L\ solution\times\frac{mol\ solute}{L\ solution}=mol\ solute\]

You know have the moles of solute you need to dissolve in the specific volume for your solution. The moles of solute need to be converted to the mass of solute, because we measure mass in the laboratory. Once the mass of solute is measured on a balance, it is mixed with the solvent (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). The volume of solvent is either measured out in a graduated cylinder and mixed with the solute in a beaker, or a special piece of glassware called a volumetric flask, which measures specific volumes, is used.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Preparation of a solution of known concentration using a solid solute and a volumetric flask. (Credit: The Central Science is licensed by CC BY-NC-SA 3.0. Original source: https://chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/General_Chemistry/Map%3A_Chemistry_-_The_Central_Science_(Brown_et_al.)/04%3A_Reactions_in_Aqueous_Solution/4.05%3A_Concentration_of_Solutions)

A chemist wants to make 250. mL of \(3.0\times10^{-2}\ M\) NaCl aqeuous solution. How many grams of NaCl should they measure out to make the solution?

Solution

The solution requires \(3.00\times10^{-2}\ moles\) per one liter of solution. The moles can be calculated with unit conversion, with the volume as the starting point and the molarity as the conversion factor. The volume units need to be same in order to cancel out. You can convert 250. mL to liters or convert the one liter to milliliters. Either will produce the same value for moles.

\[250.\ mL\times\frac{1\ L}{1000\ mL}=0.250\ mL\]

\[0.250\ L\times3.00\times10^{-2}\ \frac{mol}{L}=7.50\times10^{-3}\ mol\]

The solution needs \(7.50\times10^{-3}\) moles of NaCl dissolved in 250. mL of water. The moles of NaCl can be converted into grams using its molar mass. The addition to determine NaCl's molar mass is not shown; most chemical containers will have formula mass on them. You have to calculate molar mass if the formula mass is not readily available.

\[7.50\times10^{-3}\ mol\times58.44\ \frac{g}{mol}=0.438\ g\]

The chemist would need to measure out 0.438 grams of NaCl to make the solution.

Your laboratory requires making 100. mL of a \(5.00\times10^{-3}\ M\) aqeous solution of MgI2. How many grams of MgI2 should you measure out?

- Answer

-

0.139 g MgI2

Dilution of Solutions

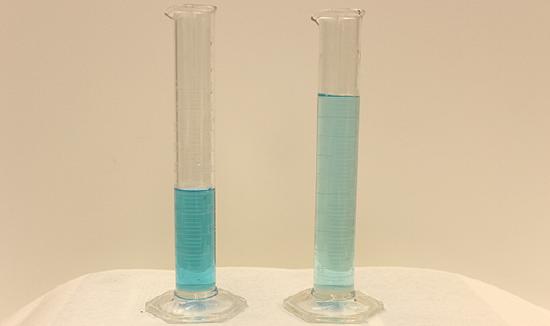

Dilution is the process whereby the concentration of a solution is lessened by the addition of solvent. For example, we might say that a glass of iced tea becomes increasingly diluted as the ice melts. The water from the melting ice increases the volume of the solvent (water) and the overall volume of the solution (iced tea), thereby reducing the relative concentrations of the solutes that give the beverage its taste (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)).

Dilution is also a common means of preparing solutions of a desired concentration. By adding solvent to a measured portion of a more concentrated stock solution, we can achieve a particular concentration. For example, commercial pesticides are typically sold as solutions in which the active ingredients are far more concentrated than is appropriate for their application. Before they can be used on crops, the pesticides must be diluted. This is also a very common practice for the preparation of a number of common laboratory reagents (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)).

A simple mathematical relationship can be used to relate the volumes and concentrations of a solution before and after the dilution process. According to the definition of molarity, the molar amount of solute in a solution is equal to the product of the solution’s molarity and its volume in liters:

\[n=MV \nonumber \]

Applying units to \(n=MV \nonumber \) shows how the equation comes together.

\[mol\ solute\ =\ \frac{mol\ solute}{L\ solution}\times L\ solution\]

Expressions like these may be written for a solution before and after it is diluted:

\[n_1=M_1V_1 \nonumber \]

\[n_2=M_2V_2 \nonumber \]

where the subscripts “1” and “2” refer to the solution before and after the dilution, respectively. Since the dilution process does not change the amount of solute in the solution,n1 = n2. Thus, these two equations may be set equal to one another:

\[M_1V_1=M_2V_2 \nonumber \]

This relation is commonly referred to as the dilution equation. Although we derived this equation using molarity as the unit of concentration and liters as the unit of volume, other units of concentration and volume may be used, so long as the units properly cancel per the factor-label method. Reflecting this versatility, the dilution equation can also be written in the more general form:

\[C_1V_1=C_2V_2 \nonumber \]

where \(C\) and \(V\) are concentration and volume, respectively.

If 0.850 L of a 5.00-M solution of copper nitrate, Cu(NO3)2, is diluted to a volume of 1.80 L by the addition of water, what is the molarity of the diluted solution?

Solution

We are given the volume and concentration of a stock solution, V1 and C1, and the volume of the resultant diluted solution, V2. We need to find the concentration of the diluted solution, C2. We thus rearrange the dilution equation in order to isolate C2:

\[C_1V_1=C_2V_2 \nonumber \]

\[C_2=\dfrac{C_1V_1}{V_2} \nonumber \]

Since the stock solution is being diluted by more than two-fold (volume is increased from 0.85 L to 1.80 L), we would expect the diluted solution’s concentration to be less than one-half 5 M. We will compare this ballpark estimate to the calculated result to check for any gross errors in computation (for example, such as an improper substitution of the given quantities). Substituting the given values for the terms on the right side of this equation yields:

\[C_2=\mathrm{\dfrac{0.850\:L\times 5.00\:\dfrac{mol}{L}}{1.80\: L}}=2.36\:M \nonumber \]

This result compares well to our ballpark estimate (it’s a bit less than one-half the stock concentration, 5 M).

What is the concentration of the solution that results from diluting 25.0 mL of a 2.04-M solution of CH3OH to 500.0 mL?

- Answer

-

0.102 M \(CH_3OH\)

What volume of 0.12 M HBr can be prepared from 11 mL (0.011 L) of 0.45 M HBr?

Solution

We are given the volume and concentration of a stock solution, V1 and C1, and the concentration of the resultant diluted solution, C2. We need to find the volume of the diluted solution, V2. We thus rearrange the dilution equation in order to isolate V2:

\[C_1V_1=C_2V_2 \nonumber \]

\[V_2=\dfrac{C_1V_1}{C_2} \nonumber \]

Since the diluted concentration (0.12 M) is slightly more than one-fourth the original concentration (0.45 M), we would expect the volume of the diluted solution to be roughly four times the original volume, or around 44 mL. Substituting the given values and solving for the unknown volume yields:

\[V_2=\dfrac{(0.45\:M)(0.011\: \ce L)}{(0.12\:M)} \nonumber \]

\[V_2=\mathrm{0.041\:L} \nonumber \]

The volume of the 0.12-M solution is 0.041 L (41 mL). The result is reasonable and compares well with our rough estimate.

A laboratory experiment calls for 0.125 M \(HNO_3\). What volume of 0.125 M \(HNO_3\) can be prepared from 0.250 L of 1.88 M \(HNO_3\)?

- Answer

-

3.76 L

What volume of 1.59 M KOH is required to prepare 5.00 L of 0.100 M KOH?

Solution

We are given the concentration of a stock solution, C1, and the volume and concentration of the resultant diluted solution, V2 and C2. We need to find the volume of the stock solution, V1. We thus rearrange the dilution equation in order to isolate V1:

\[C_1V_1=C_2V_2 \nonumber \]

\[V_1=\dfrac{C_2V_2}{C_1} \nonumber \]

Since the concentration of the diluted solution 0.100 M is roughly one-sixteenth that of the stock solution (1.59 M), we would expect the volume of the stock solution to be about one-sixteenth that of the diluted solution, or around 0.3 liters. Substituting the given values and solving for the unknown volume yields:

\[V_1=\dfrac{(0.100\:M)(5.00\:\ce L)}{1.59\:M} \nonumber \]

\[V_1=0.314\:\ce L \nonumber \]

Thus, we would need 0.314 L of the 1.59-M solution to prepare the desired solution. This result is consistent with our rough estimate.

What volume of a 0.575-M solution of glucose, C6H12O6, can be prepared from 50.00 mL of a 3.00-M glucose solution?

- Answer

-

0.261 L

Calculations Involving Dilution: https://youtu.be/Yq3cNk29_Ao

Summary

Solutions are homogeneous mixtures. Many solutions contain one component, called the solvent, in which other components, called solutes, are dissolved. An aqueous solution is one for which the solvent is water. The concentration of a solution is a measure of the relative amount of solute in a given amount of solution. Concentrations may be measured using various units, with one very useful unit being molarity, defined as the number of moles of solute per liter of solution. The solute concentration of a solution may be decreased by adding solvent, a process referred to as dilution. The dilution equation is a simple relation between concentrations and volumes of a solution before and after dilution.

Key Equations

- \(M=\mathrm{\dfrac{mol\: solute}{L\: solution}}\)

- C1V1 = C2V2

Glossary

- aqueous solution

- solution for which water is the solvent

- concentrated

- qualitative term for a solution containing solute at a relatively high concentration

- concentration

- quantitative measure of the relative amounts of solute and solvent present in a solution

- dilute

- qualitative term for a solution containing solute at a relatively low concentration

- dilution

- process of adding solvent to a solution in order to lower the concentration of solutes

- dissolved

- describes the process by which solute components are dispersed in a solvent

- molarity (M)

- unit of concentration, defined as the number of moles of solute dissolved in 1 liter of solution

- solute

- solution component present in a concentration less than that of the solvent

- solvent

- solution component present in a concentration that is higher relative to other components