2.3: Chemical Formulas

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 432410

- Scott Van Bramer

- Widener University

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Learning Objectives

- Symbolize the composition of molecules using molecular formulas and empirical formulas

- Represent the bonding arrangement of atoms within molecules using structural formulas

- Define ionic and molecular (covalent) compounds

- Predict the type of compound formed from elements based on their location within the periodic table

- Determine formulas for simple ionic compounds

- Derive names for common types of inorganic compounds using a systematic approach.

- Describe how to name binary covalent compounds including acids and oxyacids.

Elements, Molecules, and Compounds

Elements and Molecules

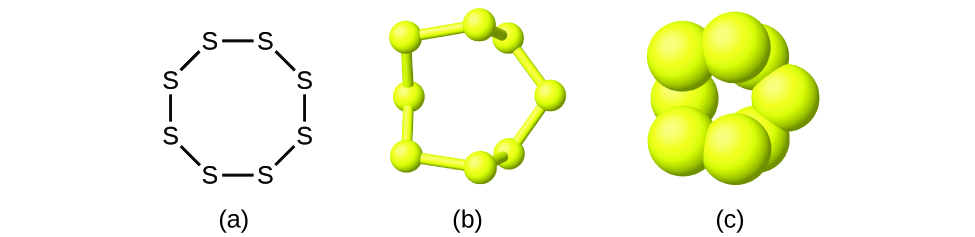

Although many elements consist of discrete, individual atoms, some exist as molecules made up of two or more atoms of the element chemically bonded together. For example, most samples of the elements hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen are composed of molecules that contain two atoms each (called diatomic molecules) and thus have the molecular formulas H2, O2, and N2, respectively. Other elements commonly found as diatomic molecules are fluorine (F2), chlorine (Cl2), bromine (Br2), and iodine (I2). The most common form of the element sulfur is composed of molecules that consist of eight atoms of sulfur; its molecular formula is S8 (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)).

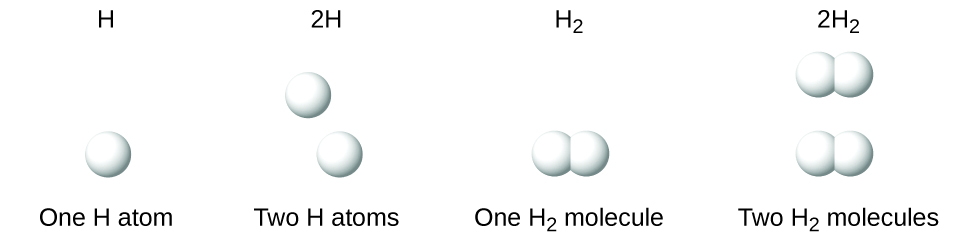

A molecular formula is a representation of a molecule that uses chemical symbols to indicate the types of atoms followed by subscripts to show the number of atoms of each type in the molecule. (A subscript is used only when more than one atom of a given type is present.) Molecular formulas are also used as abbreviations for the names of compounds. It is important to note that a subscript following a symbol and a number in front of a symbol do not represent the same thing; for example, H2 and 2H represent distinctly different species. H2 is a molecular formula; it represents a diatomic molecule of hydrogen, consisting of two atoms of the element that are chemically bonded together. The expression 2H, on the other hand, indicates two separate hydrogen atoms that are not combined as a unit. The expression 2H2 represents two molecules of diatomic hydrogen (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)).

Compounds and Molecules

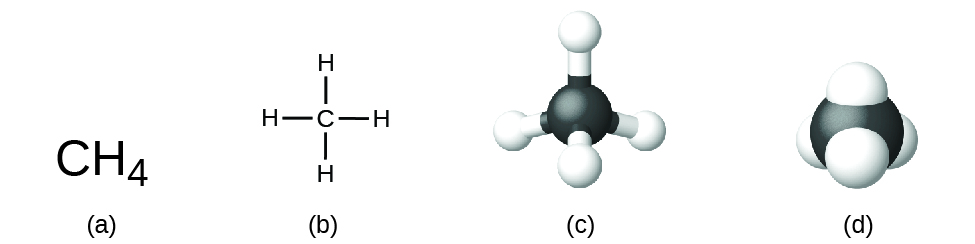

Compounds are formed when two or more elements chemically combine, resulting in the formation of bonds. If these two elements are non-metals the compound is a molecular compound. The structural formula for a compound gives the same information as its molecular formula (the types and numbers of atoms in the molecule) but also shows how the atoms are connected in the molecule. The structural formula for methane contains symbols for one C atom and four H atoms, indicating the number of atoms in the molecule (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). The lines represent bonds that hold the atoms together. (A chemical bond is an attraction between atoms or ions that holds them together in a molecule or a crystal.) These molecular compounds (covalent compounds) result when atoms share electrons. Covalent bonding is an important and extensive concept in chemistry, and it will be treated in considerable detail in a later chapter of this text. We can often identify molecular compounds on the basis of their physical properties. Under normal conditions, molecular compounds often exist as gases, low-boiling liquids, and low-melting solids, although many important exceptions exist.We will discuss chemical bonds and see how to predict the arrangement of atoms in a molecule later. For now, simply know that the lines are an indication of how the atoms are connected in a molecule. A ball-and-stick model shows the geometric arrangement of the atoms with atomic sizes not to scale, and a space-filling model shows the relative sizes of the atoms.

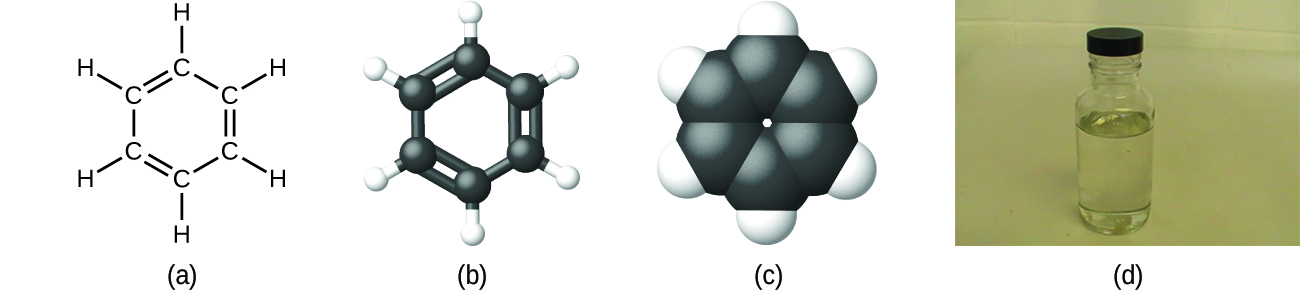

We can describe a compound with a molecular formula, in which the subscripts indicate the actual numbers of atoms of each element in a molecule of the compound. We can also describe the composition of these compounds with an empirical formula, which indicates the types of atoms present and the simplest whole-number ratio of the number of atoms (or ions) in the compound. For example, it can be determined experimentally that benzene contains two elements, carbon (C) and hydrogen (H), and that for every carbon atom in benzene, there is one hydrogen atom. Thus, the empirical formula is CH. An experimental determination of the molecular mass reveals that a molecule of benzene contains six carbon atoms and six hydrogen atoms, so the molecular formula for benzene is C6H6 (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)).

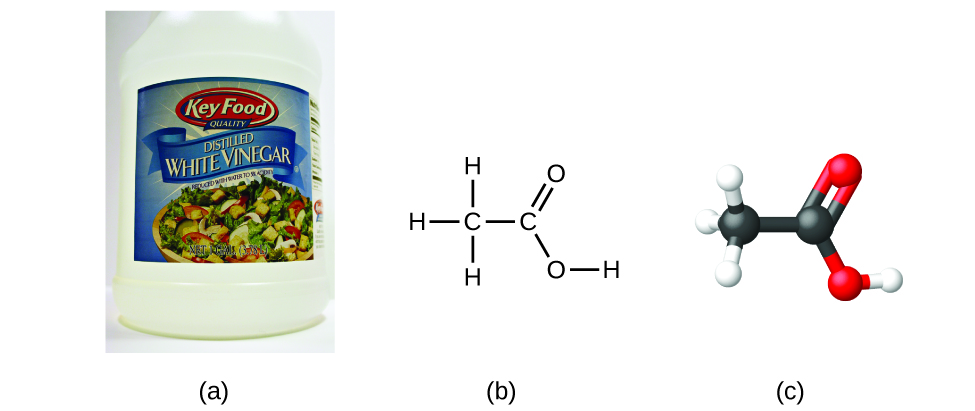

If we know a compound’s formula, we can easily determine the empirical formula. For example, the molecular formula for acetic acid, the component that gives vinegar its sharp taste, is C2H4O2. This formula indicates that a molecule of acetic acid (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)) contains two carbon atoms, four hydrogen atoms, and two oxygen atoms. The ratio of atoms is 2:4:2. Dividing by the lowest common denominator (2) gives the simplest, whole-number ratio of atoms, 1:2:1, so the empirical formula is CH2O. The molecular formula is always a whole-number multiple of an empirical formula.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Empirical and Molecular Formulas

Molecules of glucose (blood sugar) contain 6 carbon atoms, 12 hydrogen atoms, and 6 oxygen atoms. What are the molecular and empirical formulas of glucose?

Solution

The molecular formula is C6H12O6 because one molecule actually contains 6 C, 12 H, and 6 O atoms. The simplest whole-number ratio of C to H to O atoms in glucose is 1:2:1, so the empirical formula is CH2O.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

A molecule of metaldehyde (a pesticide used for snails and slugs) contains 8 carbon atoms, 16 hydrogen atoms, and 4 oxygen atoms. What are the molecular and empirical formulas of metaldehyde?

- Answer

-

Molecular formula, C8H16O4; empirical formula, C2H4O

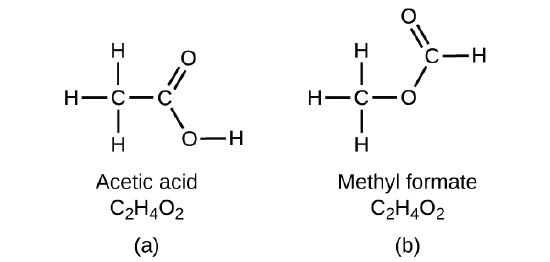

It is important to be aware that it may be possible for the same atoms to be arranged in different ways: Compounds with the same molecular formula may have different atom-to-atom bonding and therefore different structures. For example, could there be another compound with the same formula as acetic acid, C2H4O2? And if so, what would be the structure of its molecules?

If you predict that another compound with the formula C2H4O2 could exist, then you demonstrated good chemical insight and are correct. Two C atoms, four H atoms, and two O atoms can also be arranged to form methyl formate, which is used in manufacturing, as an insecticide, and for quick-drying finishes. Methyl formate molecules have one of the oxygen atoms between the two carbon atoms, differing from the arrangement in acetic acid molecules. Acetic acid and methyl formate are examples of isomers—compounds with the same chemical formula but different molecular structures (Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)). Note that this small difference in the arrangement of the atoms has a major effect on their respective chemical properties. You would certainly not want to use a solution of methyl formate as a substitute for a solution of acetic acid (vinegar) when you make salad dressing.

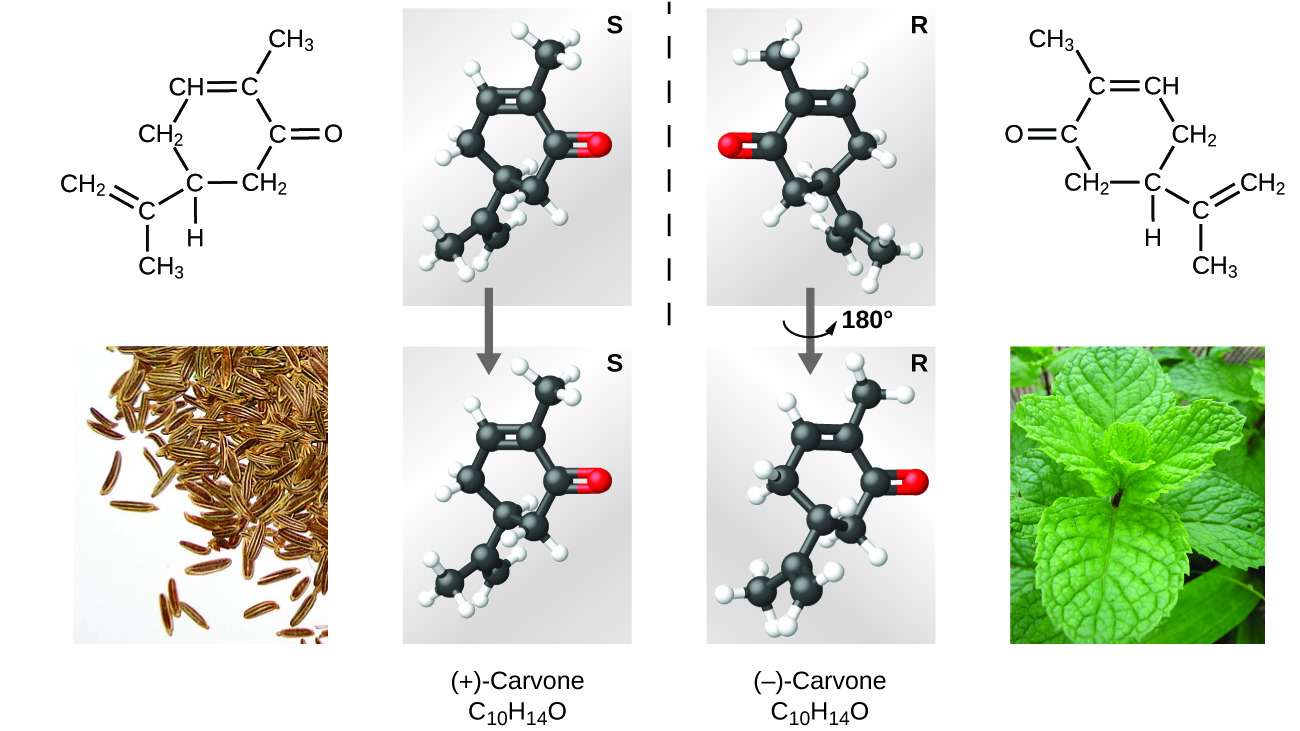

Many types of isomers exist (Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)). Acetic acid and methyl formate are structural isomers, compounds in which the molecules differ in how the atoms are connected to each other. There are also various types of spatial isomers, in which the relative orientations of the atoms in space can be different. For example, the compound carvone (found in caraway seeds, spearmint, and mandarin orange peels) consists of two isomers that are mirror images of each other. S-(+)-carvone smells like caraway, and R-(−)-carvone smells like spearmint.

Naming Molecular Compounds

When two nonmetallic elements form a molecular compound, several combination ratios are often possible. For example, carbon and oxygen can form the compounds CO and CO2. Since these are different substances with different properties, they cannot both be called carbon oxide. To distinguish these two compounds prefixes are added to specify the numbers of atoms of each element. The name of the more metallic element (the one farther to the left and/or bottom of the periodic table) is first, followed by the name of the more nonmetallic element (the one farther to the right and/or top) with its ending changed to the suffix –ide. The numbers of atoms of each element are designated by the Greek prefixes shown in Table \(\PageIndex{5}\).

| Number | Prefix | Number | Prefix | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (sometimes omitted) | mono- | 6 | hexa- | |

| 2 | di- | 7 | hepta- | |

| 3 | tri- | 8 | octa- | |

| 4 | tetra- | 9 | nona- | |

| 5 | penta- | 10 | deca- |

When only one atom of the first element is present, the prefix mono- is usually deleted from that part. Thus, \(\ce{CO}\) is named carbon monoxide, and \(\ce{CO2}\) is called carbon dioxide. When two vowels are adjacent, the a in the Greek prefix is usually dropped. Some other examples are shown in Table \(\PageIndex{6}\).

| Compound | Name | Compound | Name | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SO2 | sulfur dioxide | BCl3 | boron trichloride | |

| SO3 | sulfur trioxide | SF6 | sulfur hexafluoride | |

| NO2 | nitrogen dioxide | PF5 | phosphorus pentafluoride | |

| N2O4 | dinitrogen tetroxide | P4O10 | tetraphosphorus decaoxide | |

| N2O5 | dinitrogen pentoxide | IF7 | iodine heptafluoride |

There are a few common names that you may encounter as you continue your study of chemistry. For example, although the proper name for NO is nitrogen monoxide, it is often called nitric oxide. Similarly, dinitrogen monioxide, N2O, may be called nitrous oxide. And H2O is usually called water, not dihydrogen monoxide. Be careful when you encounter these common names to make sure you know what formula to use - it is a good idea to double check by looking these up.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\): Naming Covalent Compounds

Name the following covalent compounds:

- SF6

- N2O3

- Cl2O7

- P4O6

Solution

Because these compounds consist solely of nonmetals, we use prefixes to designate the number of atoms of each element:

- sulfur hexafluoride

- dinitrogen trioxide

- dichlorine heptoxide

- tetraphosphorus hexoxide

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Write the formulas for the following compounds:

- phosphorus pentachloride

- dinitrogen monoxide

- iodine heptafluoride

- carbon tetrachloride

- Answer a

-

PCl5

- Answer b

-

N2O

- Answer c

-

IF7

- Answer d

-

CCl4

Ionic Compounds

Introduction

Compounds are formed when two or more elements chemically combine, resulting in the formation of bonds. When two non-metals like hydrogen and oxygen react they form water molecules H2O - which is a molecular compound. However, when a metal and a non-metal like sodium and chlorine react they form table salt which is an ionic compound. The result is not a molecule. This ionic compound has elements in a fixed ratio 1 Na to 1 Cl but the structure is very different from a molecular compound. The empirical formula for table salt is NaCl and the structure contains a large number of interconnected atoms. The empirical formula just indicates the types of atoms present and the simplest whole-number ratio of the number of atoms (or ions) in the compound.

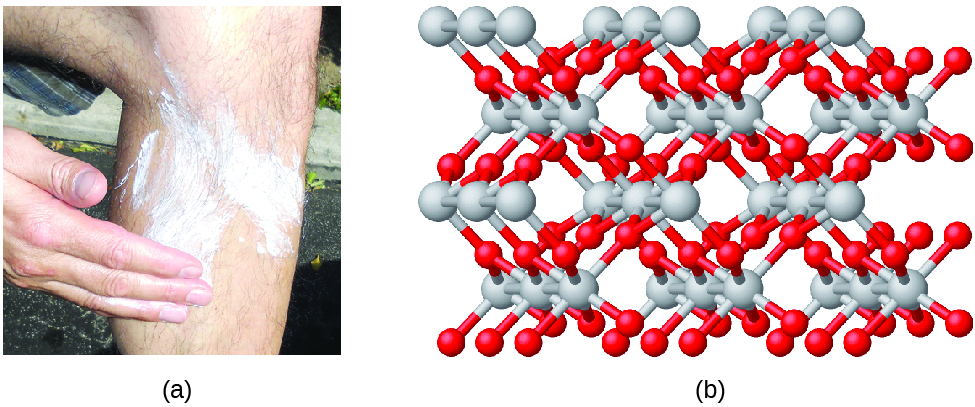

Another example is titanium (IV) oxide. Titanium (IV) oxide is used as pigment in white paint and in the thick, white, blocking type of sunscreen. It has an empirical formula of TiO2 that identifies the elements titanium (Ti) and oxygen (O) as the constituents of titanium (IV) oxide. The empirical formula shows there are twice as many oxygen atoms as titanium atoms. The structure, however, is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{4b}\).

Forming Ions

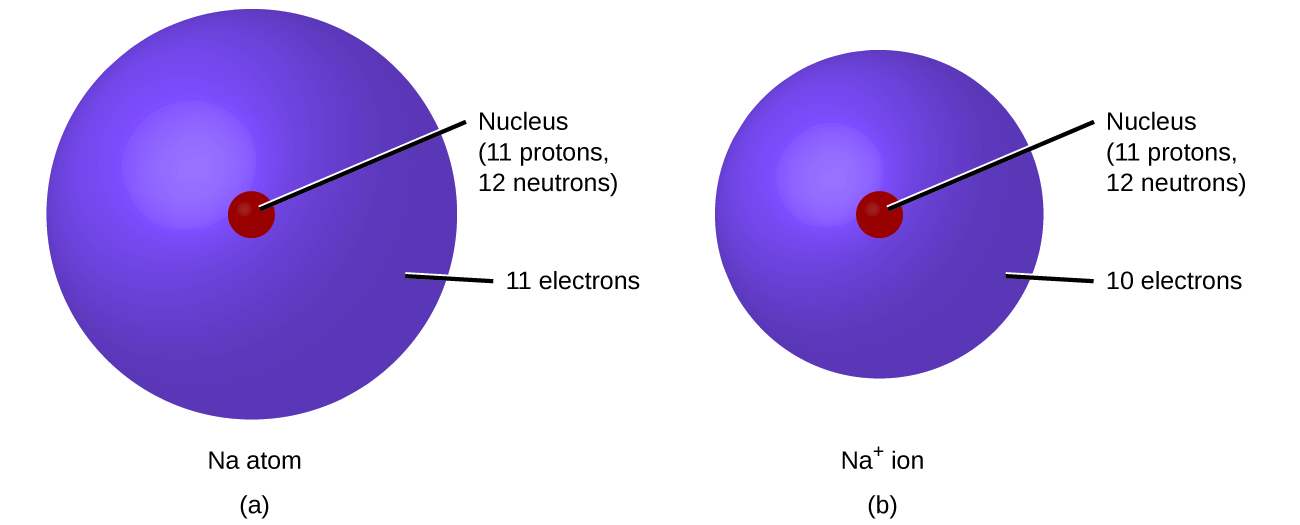

In ordinary chemical reactions, the nucleus of each atom (and thus the identity of the element) remains unchanged. Electrons, however, can be added to atoms by transfer from other atoms, lost by transfer to other atoms, or shared with other atoms. The transfer and sharing of electrons among atoms govern the chemistry of the elements. During the formation of some compounds, atoms gain or lose electrons, and form electrically charged particles called ions (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)).

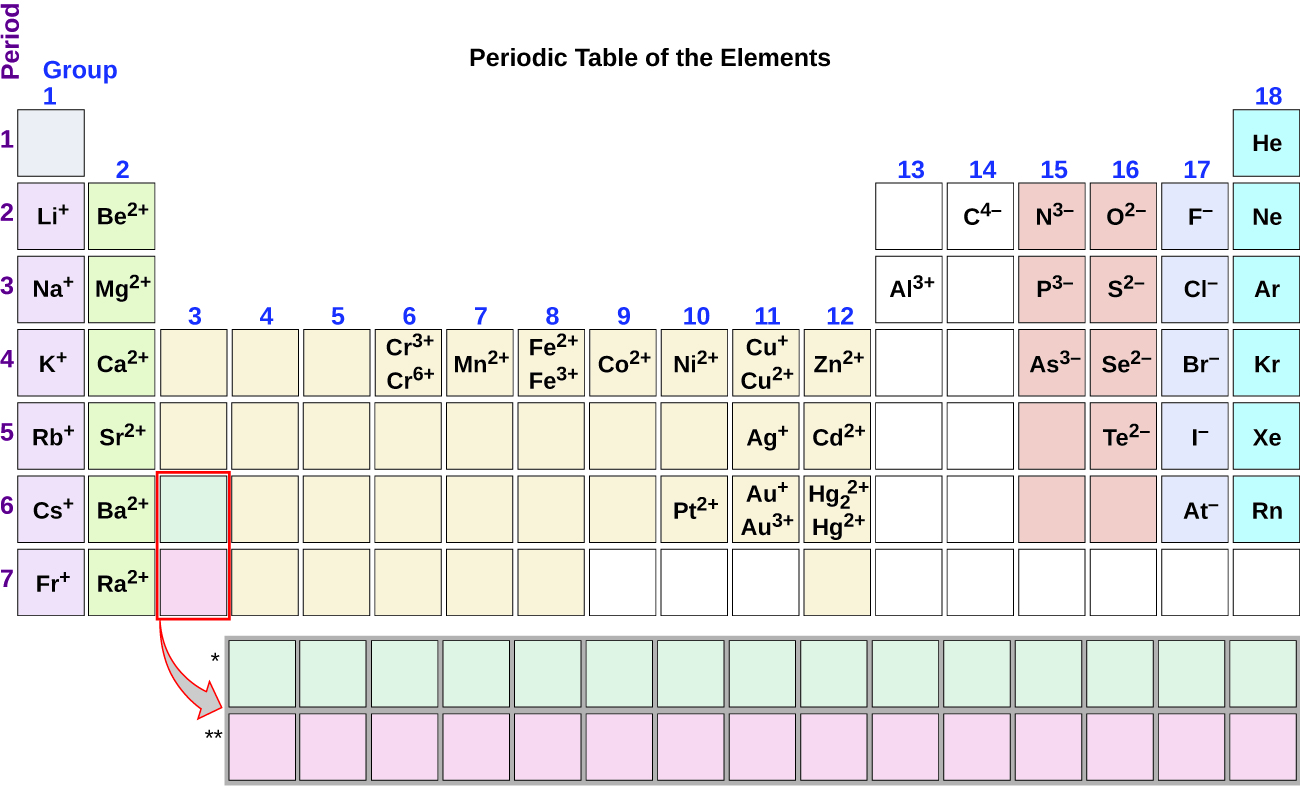

You can use the periodic table to predict whether an atom will form an anion or a cation, and you can often predict the charge of the resulting ion. Atoms of many main-group metals lose enough electrons to leave them with the same number of electrons as an atom of the preceding noble gas. To illustrate, an atom of an alkali metal (group 1) loses one electron and forms a cation with a 1+ charge; an alkaline earth metal (group 2) loses two electrons and forms a cation with a 2+ charge, and so on. For example, a neutral calcium atom, with 20 protons and 20 electrons, readily loses two electrons. This results in a cation with 20 protons, 18 electrons, and a 2+ charge. It has the same number of electrons as atoms of the preceding noble gas, argon, and is symbolized Ca2+. The name of a metal ion is the same as the name of the metal atom from which it forms, so Ca2+ is called a calcium ion.

When atoms of nonmetal elements form ions, they generally gain enough electrons to give them the same number of electrons as an atom of the next noble gas in the periodic table. Atoms of group 17 gain one electron and form anions with a 1− charge; atoms of group 16 gain two electrons and form ions with a 2− charge, and so on. For example, the neutral bromine atom, with 35 protons and 35 electrons, can gain one electron to provide it with 36 electrons. This results in an anion with 35 protons, 36 electrons, and a 1− charge. It has the same number of electrons as atoms of the next noble gas, krypton, and is symbolized Br−. (A discussion of the theory supporting the favored status of noble gas electron numbers reflected in these predictive rules for ion formation is provided in a later chapter of this text.)

Note the usefulness of the periodic table in predicting likely ion formation and charge (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)). Moving from the far left to the right on the periodic table, main-group elements tend to form cations with a charge equal to the group number. That is, group 1 elements form 1+ ions; group 2 elements form 2+ ions, and so on. Moving from the far right to the left on the periodic table, elements often form anions with a negative charge equal to the number of groups moved left from the noble gases. For example, group 17 elements (one group left of the noble gases) form 1− ions; group 16 elements (two groups left) form 2− ions, and so on. This trend can be used as a guide in many cases, but its predictive value decreases when moving toward the center of the periodic table. In fact, transition metals and some other metals often exhibit variable charges that are not predictable by their location in the table. For example, copper can form ions with a 1+ or 2+ charge, and iron can form ions with a 2+ or 3+ charge.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\): Composition of Ions

An ion found in some compounds used as antiperspirants contains 13 protons and 10 electrons. What is its symbol?

Solution

Because the number of protons remains unchanged when an atom forms an ion, the atomic number of the element must be 13. Knowing this lets us use the periodic table to identify the element as Al (aluminum). The Al atom has lost three electrons and thus has three more positive charges (13) than it has electrons (10). This is the aluminum cation, Al3+.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Give the symbol and name for the ion with 34 protons and 36 electrons.

- Answer

-

Se2−, the selenide ion

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\): Formation of Ions

Magnesium and nitrogen react to form an ionic compound. Predict which forms an anion, which forms a cation, and the charges of each ion. Write the symbol for each ion and name them.

Solution

Magnesium’s position in the periodic table (group 2) tells us that it is a metal. Metals form positive ions (cations). A magnesium atom must lose two electrons to have the same number electrons as an atom of the previous noble gas, neon. Thus, a magnesium atom will form a cation with two fewer electrons than protons and a charge of 2+. The symbol for the ion is Mg2+, and it is called a magnesium ion.

Nitrogen’s position in the periodic table (group 15) reveals that it is a nonmetal. Nonmetals form negative ions (anions). A nitrogen atom must gain three electrons to have the same number of electrons as an atom of the following noble gas, neon. Thus, a nitrogen atom will form an anion with three more electrons than protons and a charge of 3−. The symbol for the ion is N3−, and it is called a nitride ion.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Aluminum and carbon react to form an ionic compound. Predict which forms an anion, which forms a cation, and the charges of each ion. Write the symbol for each ion and name them.

- Answer

-

Al will form a cation with a charge of 3+: Al3+, an aluminum ion. Carbon will form an anion with a charge of 4−: C4−, a carbide ion.

Polyatomic Ions

The ions that we have discussed so far are called monatomic ions, that is, they are ions formed from only one atom. We also find many polyatomic ions. These ions, which act as discrete units, are electrically charged molecules (a group of bonded atoms with an overall charge). Some of the more important polyatomic ions are listed in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\). Oxyanions are polyatomic ions that contain one or more oxygen atoms. At this point in your study of chemistry, you should memorize the names, formulas, and charges of the most common polyatomic ions. Because you will use them repeatedly, they will soon become familiar.

| Name | Formula |

|---|---|

| ammonium | \(\ce{NH4+}\) |

| hydronium | \(\ce{H_3O^+}\) |

| hydroxide | \(\ce{OH^-}\) |

| acetate | \(\ce{CH_3COO^-}\) |

| cyanide | \(\ce{CN^-}\) |

| carbonate | \(\ce{CO_3^{2-}}\) |

|

hydrogen carbonate (bicarbonate) |

\(\ce{HCO_3^-}\) |

| nitrate | \(\ce{NO_3^-}\) |

| nitrite | \(\ce{NO_2^-}\) |

| sulfate | \(\ce{SO_4^{2-}}\) |

| hydrogen sulfate (bisulfate) | \(\ce{HSO_4^-}\) |

| sulfite | \(\ce{SO_3^{2-}}\) |

| hydrogen sulfite (bisulfite) | \(\ce{HSO_3^-}\) |

| phosphate | \(\ce{PO_4^{3-}}\) |

| hydrogen phosphate (biphosphate) | \(\ce{HPO_4^{2-}}\) |

| dihydrogen phosphate (dibiphosphate) | \(\ce{H_2PO_4^-}\) |

Note that there is a system for naming some polyatomic ions; -ate and -ite are suffixes designating polyatomic ions containing more or fewer oxygen atoms. Unfortunately, the number of oxygen atoms corresponding to a given suffix or prefix is not consistent; for example, nitrate is \(\ce{NO3-}\) while sulfate is \(\ce{SO4^{2-}}\).

The nature of the attractive forces that hold atoms or ions together within a compound is the basis for classifying chemical bonding. When electrons are transferred and ions form, ionic bonds result. Ionic bonds are electrostatic forces of attraction, that is, the attractive forces experienced between objects of opposite electrical charge (in this case, cations and anions). When electrons are “shared” and molecules form, covalent bonds result. Covalent bonds are the attractive forces between the positively charged nuclei of the bonded atoms and one or more pairs of electrons that are located between the atoms. Compounds are classified as ionic or molecular (covalent) on the basis of the bonds present in them.

Forming Ionic Compounds

When an element composed of atoms that readily lose electrons (a metal) reacts with an element composed of atoms that readily gain electrons (a nonmetal), a transfer of electrons usually occurs, producing ions. The compound formed by this transfer is stabilized by the electrostatic attractions (ionic bonds) between the ions of opposite charge present in the compound. For example, when each sodium atom in a sample of sodium metal (group 1) gives up one electron to form a sodium cation, Na+, and each chlorine atom in a sample of chlorine gas (group 17) accepts one electron to form a chloride anion, Cl−, the resulting compound, NaCl, is composed of sodium ions and chloride ions in the ratio of one Na+ ion for each Cl− ion. Similarly, each calcium atom (group 2) can give up two electrons and transfer one to each of two chlorine atoms to form CaCl2, which is composed of Ca2+ and Cl− ions in the ratio of one Ca2+ ion to two Cl− ions.

A compound that contains ions and is held together by ionic bonds is called an ionic compound. The periodic table can help us recognize many of the compounds that are ionic: When a metal is combined with one or more nonmetals, the compound is usually ionic. This guideline works well for predicting ionic compound formation for most of the compounds typically encountered in an introductory chemistry course. However, it is not always true (for example, aluminum chloride, AlCl3, is not ionic).

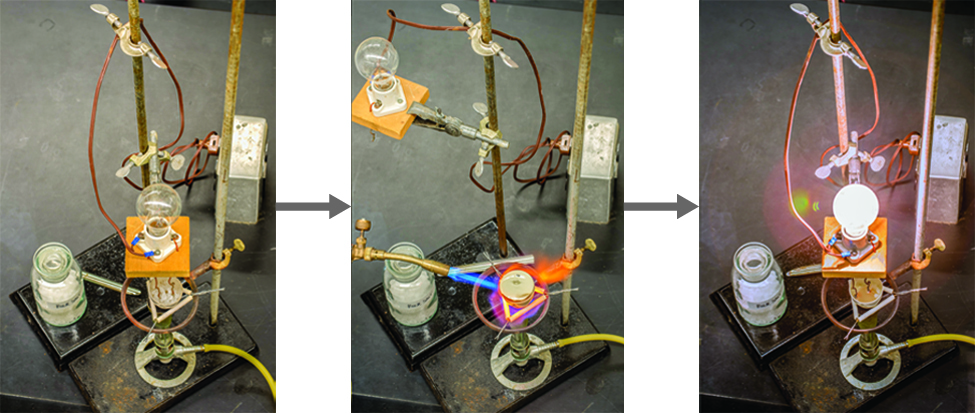

You can often recognize ionic compounds because of their properties. Ionic compounds are solids that typically melt at high temperatures and boil at even higher temperatures. For example, sodium chloride melts at 801 °C and boils at 1413 °C. (As a comparison, the molecular compound water melts at 0 °C and boils at 100 °C.) In solid form, an ionic compound is not electrically conductive because its ions are unable to flow (“electricity” is the flow of charged particles). When molten, however, it can conduct electricity because its ions are able to move freely through the liquid (Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)).

In every ionic compound, the total number of positive charges of the cations equals the total number of negative charges of the anions. Thus, ionic compounds are electrically neutral overall, even though they contain positive and negative ions. We can use this observation to help us write the formula of an ionic compound. The formula of an ionic compound must have a ratio of ions such that the numbers of positive and negative charges are equal.

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\): Predicting the Formula of an Ionic Compound

The gemstone sapphire (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)) is mostly a compound of aluminum and oxygen that contains aluminum cations, Al3+, and oxygen anions, O2−. What is the formula of this compound?

Solution Because the ionic compound must be electrically neutral, it must have the same number of positive and negative charges. Two aluminum ions, each with a charge of 3+, would give us six positive charges, and three oxide ions, each with a charge of 2−, would give us six negative charges. The formula would be Al2O3.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Predict the formula of the ionic compound formed between the sodium cation, Na+, and the sulfide anion, S2−.

- Answer

-

Na2S

Many ionic compounds contain polyatomic ions (Table \(\PageIndex{1}\)) as the cation, the anion, or both. As with simple ionic compounds, these compounds must also be electrically neutral, so their formulas can be predicted by treating the polyatomic ions as discrete units. We use parentheses in a formula to indicate a group of atoms that behave as a unit. For example, the formula for calcium phosphate, one of the minerals in our bones, is Ca3(PO4)2. This formula indicates that there are three calcium ions (Ca2+) for every two phosphate \(\left(\ce{PO4^{3-}}\right)\) groups. The \(\ce{PO4^{3-}}\) groups are discrete units, each consisting of one phosphorus atom and four oxygen atoms, and having an overall charge of 3−. The compound is electrically neutral, and its formula shows a total count of three Ca, two P, and eight O atoms.

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\): Predicting the Formula of a Compound with a Polyatomic Anion

Baking powder contains calcium dihydrogen phosphate, an ionic compound composed of the ions Ca2+ and \(\ce{H2PO4-}\). What is the formula of this compound?

Solution

The positive and negative charges must balance, and this ionic compound must be electrically neutral. Thus, we must have two negative charges to balance the 2+ charge of the calcium ion. This requires a ratio of one Ca2+ ion to two \(\ce{H2PO4-}\) ions. We designate this by enclosing the formula for the dihydrogen phosphate ion in parentheses and adding a subscript 2. The formula is Ca(H2PO4)2.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{4}\)

Predict the formula of the ionic compound formed between the lithium ion and the sulfate ion, \(\ce{SO4^2-}\) (Hint: Use the periodic table to predict the sign and the charge on the lithium ion.)

- Answer

-

Li2SO4

Because an ionic compound is not made up of single, discrete molecules, it may not be properly symbolized using a molecular formula. Instead, ionic compounds must be symbolized by a formula indicating the relative numbers of its constituent ions. For compounds containing only monatomic ions (such as NaCl) and for many compounds containing polyatomic ions (such as CaSO4), these formulas are just the empirical formulas introduced earlier in this chapter. However, the formulas for some ionic compounds containing polyatomic ions are not empirical formulas. For example, the ionic compound sodium oxalate is comprised of Na+ and \(\ce{C2O4^2-}\) ions combined in a 2:1 ratio, and its formula is written as Na2C2O4. The subscripts in this formula are not the smallest-possible whole numbers, as each can be divided by 2 to yield the empirical formula, NaCO2. This is not the accepted formula for sodium oxalate, however, as it does not accurately represent the compound’s polyatomic anion, \(\ce{C2O4^2-}\).

Naming Ionic Compounds

This section describes how to name simple ionic compounds, such as NaCl, CaCO3, and N2O4. The simplest of these are binary compounds, those containing only two elements, but we will also consider how to name ionic compounds containing polyatomic ions. There are different systems for ionic compounds where the metal always forms ions with the same charge vs metals that form ions with different charges.

Ionic Compounds Containing Metals With a Single Charge

The name of a binary compound containing monatomic ions consists of the name of the metal followed by the name of the nonmetal. The nonmetal has its ending replaced by the suffix –ide). Some examples are given in Table \(\PageIndex{2}\).

| NaCl, sodium chloride | Na2O, sodium oxide |

| KBr, potassium bromide | CdS, cadmium sulfide |

| CaI2, calcium iodide | Mg3N2, magnesium nitride |

| CsF, cesium fluoride | Ca3P2, calcium phosphide |

| LiCl, lithium chloride | Al4C3, aluminum carbide |

Compounds Containing Polyatomic Ions

Compounds containing polyatomic ions are named similarly to those containing only monatomic ions, except there is no need to change to an –ide ending, since a suffix is already present in the name of the anion. Examples are shown in Table \(\PageIndex{3}\).

| KC2H3O2, potassium acetate | (NH4)Cl, ammonium chloride |

| NaHCO3, sodium bicarbonate | CaSO4, calcium sulfate |

| Al2(CO3)3, aluminum carbonate | Mg3(PO4)2, magnesium phosphate |

Ionic Compounds in Your Cabinets

Every day you encounter and use a large number of ionic compounds. Some of these compounds, where they are found, and what they are used for are listed in Table \(\PageIndex{3}\). Look at the label or ingredients list on the various products that you use during the next few days, and see if you run into any of those in this table, or find other ionic compounds that you could now name or write as a formula.

| Ionic Compound | Name | Use |

|---|---|---|

| NaCl | sodium chloride | ordinary table salt |

| NaHCO3 |

sodium hydrogen carbonate or sodium bicarbonate |

baking soda; used in cooking (and in antacids) |

| Na2CO3 | sodium carbonate | washing soda; used in cleaning agents |

| CaCO3 | calcium carbonate | ingredient in antacids |

| Mg(OH)2 | magnesium hydroxide | ingredient in antacids |

| K3PO4 | potassium phosphate | food additive (many purposes) |

| Na2HPO4 |

sodium hydrogen phosphate or sodium biphosphate |

anti-caking agent; used in powdered products |

| Na2SO3 | sodium sulfite | preservative |

Compounds Containing a Metal Ion with a Variable Charge

Most of the transition metals form two or more cations with different charges. Compounds of these metals with nonmetals are named with the same method as compounds in the first category, except the charge of the metal ion is specified by a Roman numeral in parentheses after the name of the metal. The charge of the metal ion is determined from the formula of the compound and the charge of the anion. For example, consider binary ionic compounds of iron and chlorine. Iron typically exhibits a charge of either 2+ or 3+, and the two corresponding compound formulas are FeCl2 and FeCl3. The simplest name, “iron chloride,” will, in this case, be ambiguous, as it does not distinguish between these two compounds. In cases like this, the charge of the metal ion is included as a Roman numeral in parentheses immediately following the metal name. These two compounds are then unambiguously named iron(II) chloride and iron(III) chloride, respectively. Other examples are provided in Table \(\PageIndex{4}\).

| Transition Metal Ionic Compound | Name |

|---|---|

| FeCl3 | iron(III) chloride |

| FeCl2 | Iron (II) chloride |

| Cu3(PO4)2 | copper(II) phosphate |

Out-of-date nomenclature used the suffixes –ic and –ous to designate metals with higher and lower charges, respectively: Iron(III) chloride, FeCl3, was previously called ferric chloride, and iron(II) chloride, FeCl2, was known as ferrous chloride. Though this naming convention has been largely abandoned by the scientific community, it remains in use by some segments of industry. For example, you may see the words stannous fluoride on a tube of toothpaste. This represents the formula SnF2, which is more properly named tin(II) fluoride. The other fluoride of tin is SnF4, which was previously called stannic fluoride but is now named tin(IV) fluoride. If you see one of these names, look it up to make sure you have the correct charge for the metal.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Naming Ionic Compounds

Name the following ionic compounds, which contain a metal that can have more than one ionic charge:

- Fe2S3

- CuSe

- GaN

- CrCl3

- Ti2(SO4)3

Solution

The anions in these compounds have a fixed negative charge (S2−, Se2− , N3−, Cl−, and \(\ce{SO4^2-}\)), and the compounds must be neutral. Because the total number of positive charges in each compound must equal the total number of negative charges, the positive ions must be Fe3+, Cu2+, Ga3+, Cr3+, and Ti3+. These charges are used in the names of the metal ions:

- iron(III) sulfide

- copper(II) selenide

- gallium(III) nitride

- chromium(III) chloride

- titanium(III) sulfate

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Write the formulas of the following ionic compounds:

- chromium(III) phosphide

- mercury(II) sulfide

- manganese(II) phosphate

- copper(I) oxide

- chromium(VI) fluoride

- Answer a

-

CrP

- Answer b

-

HgS

- Answer c

-

Mn3(PO4)2

- Answer d

-

Cu2O

- Answer e

-

CrF6

Erin Brokovich and Chromium Contamination

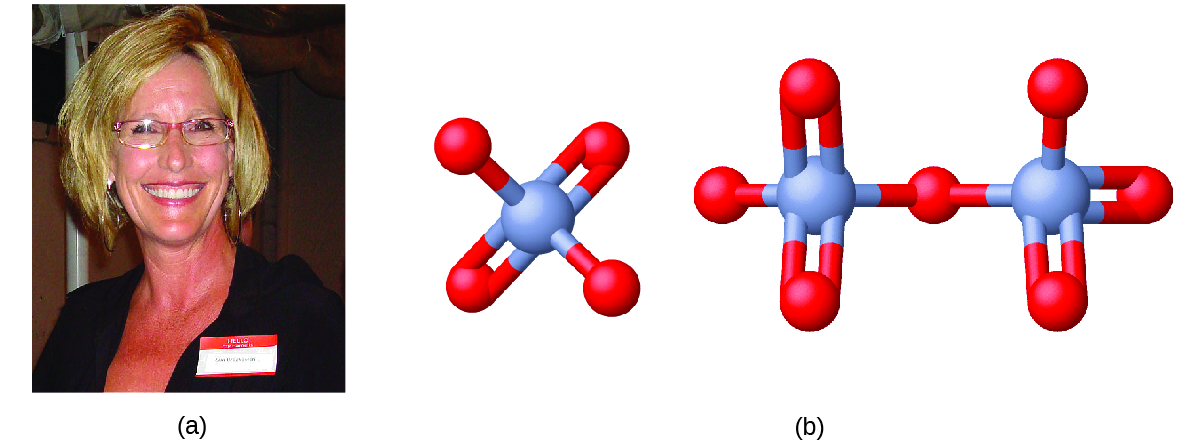

In the early 1990s, legal file clerk Erin Brockovich (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)) discovered a high rate of serious illnesses in the small town of Hinckley, California. Her investigation eventually linked the illnesses to groundwater contaminated by Cr(VI) used by Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) to fight corrosion in a nearby natural gas pipeline. As dramatized in the film Erin Brokovich (for which Julia Roberts won an Oscar), Erin and lawyer Edward Masry sued PG&E for contaminating the water near Hinckley in 1993. The settlement they won in 1996—$333 million—was the largest amount ever awarded for a direct-action lawsuit in the US at that time.

Chromium compounds are widely used in industry, such as for chrome plating, in dye-making, as preservatives, and to prevent corrosion in cooling tower water, as occurred near Hinckley. In the environment, chromium exists primarily in either the Cr(III) or Cr(VI) forms. Cr(III), an ingredient of many vitamin and nutritional supplements, forms compounds that are not very soluble in water, and it has low toxicity. Cr(VI), on the other hand, is much more toxic and forms compounds that are reasonably soluble in water. Exposure to small amounts of Cr(VI) can lead to damage of the respiratory, gastrointestinal, and immune systems, as well as the kidneys, liver, blood, and skin.

Despite cleanup efforts, Cr(VI) groundwater contamination remains a problem in Hinckley and other locations across the globe. A 2010 study by the Environmental Working Group found that of 35 US cities tested, 31 had higher levels of Cr(VI) in their tap water than the public health goal of 0.02 parts per billion set by the California Environmental Protection Agency.

Distinguishing Ionic and Molecular Compounds

Since the systems for naming molecular compounds and ionic compounds are very different, it is important to know how to distinguish these two types of compounds. Molecular compounds (covalent compounds) result when atoms share, rather than transfer (gain or lose), electrons. Covalent bonding is an important and extensive concept in chemistry, and it will be treated in considerable detail in a later chapter of this text. We can often identify molecular compounds on the basis of their physical properties. Under normal conditions, molecular compounds often exist as gases, low-boiling liquids, and low-melting solids, although many important exceptions exist. Covalent compounds are usually formed by a combination of nonmetals

In contrast, ionic compounds are usually formed when a metal and a nonmetal combine. As a result, the periodic table helps distinguish these two types of compounds. While we can use the positions of a compound’s elements in the periodic table to predict whether it is ionic or covalent at this point in our study of chemistry, you should be aware that this is a very simplistic approach that does not account for a number of interesting exceptions. Shades of gray exist between ionic and molecular compounds, and you’ll learn more about those later.

Example \(\PageIndex{5}\): Predicting the Type of Bonding in Compounds

Predict whether the following compounds are ionic or molecular:

- KI, the compound used as a source of iodine in table salt

- H2O2, the bleach and disinfectant hydrogen peroxide

- CHCl3, the anesthetic chloroform

- Li2CO3, a source of lithium in antidepressants

Solution

- Potassium (group 1) is a metal, and iodine (group 17) is a nonmetal; KI is predicted to be ionic.

- Hydrogen (group 1) is a nonmetal, and oxygen (group 16) is a nonmetal; H2O2 is predicted to be molecular.

- Carbon (group 14) is a nonmetal, hydrogen (group 1) is a nonmetal, and chlorine (group 17) is a nonmetal; CHCl3 is predicted to be molecular.

- Lithium (group 1) is a metal, and carbonate is a polyatomic ion; Li2CO3 is predicted to be ionic.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{5}\)

Using the periodic table, predict whether the following compounds are ionic or molecular:

- SO2

- CaF2

- N2H4

- Al2(SO4)3

- Answer a

-

molecular

- Answer b

-

ionic

- Answer c

-

molecular

- Answer d

-

ionic

Naming Acids

Acids are another important class of compounds. They share characteristics with both molecular and ionic compounds but they are named using a separate system of chemical nomenclature. If you are familiar with anions - both atomic and polyatomic - it is easy to identify when you need to name something as an acid because the cation is hydrogen. These compounds act as acids by releasing hydrogen ions, H+, when dissolved in water.To denote this distinct chemical property, a mixture of water with an acid is given a name derived from the compound’s name. The chemistry of acids is discussed in much greater detail in later chapters, but for now it is important that you know how to name these compounds.

Naming Binary Acids

If the compound is a binary acid (comprised of hydrogen and one other nonmetallic element):

- The word “hydrogen” is changed to the prefix hydro-

- The other nonmetallic element name is modified by adding the suffix -ic

- The word “acid” is added as a second word

For example, when the gas \(\ce{HCl}\) (hydrogen chloride) is dissolved in water, the solution is called hydrochloric acid. Several other examples of this nomenclature are shown in Table \(\PageIndex{5}\).

| Name of Gas | Name of Acid |

|---|---|

| HF(g), hydrogen fluoride | HF(aq), hydrofluoric acid |

| HCl(g), hydrogen chloride | HCl(aq), hydrochloric acid |

| H2S(g), hydrogen sulfide | H2S(aq), hydrosulfuric acid |

Naming Oxyacids

Oxyacids are compounds that contain hydrogen and a polyatomic ion with oxygen. These compounds and are bonded in such a way as to impart acidic properties to the compound (you will learn the details of this in a later chapter). To name oxyacids:

- Omit “hydrogen”

- Start with the root name of the anion

- Replace –ate with –ic, or –ite with –ous

- Add “acid”

For example, consider H2CO3 (which you might be tempted to call “hydrogen carbonate”). To name this correctly, “hydrogen” is omitted; the –ate of carbonate is replace with –ic; and acid is added—so its name is carbonic acid. Other examples are given in Table \(\PageIndex{6}\). There are some exceptions to the general naming method (e.g., H2SO4 is called sulfuric acid, not sulfic acid, and H2SO3 is sulfurous, not sulfous, acid).

| Formula | Anion Name | Acid Name |

|---|---|---|

| HC2H3O2 | acetate | acetic acid |

| HNO3 | nitrate | nitric acid |

| HNO2 | nitrite | nitrous acid |

| H2SO4 | sulfate | sulfuric acid |

| H2SO3 | sulfite | sulfurous acid |

| H3PO4 | phosphate | phosphoric acid |

Summary

A molecular formula uses chemical symbols and subscripts to indicate the exact numbers of different atoms in a molecule or compound. An empirical formula gives the simplest, whole-number ratio of atoms in a compound. A structural formula indicates the bonding arrangement of the atoms in the molecule. Ball-and-stick and space-filling models show the geometric arrangement of atoms in a molecule. Isomers are compounds with the same molecular formula but different arrangements of atoms.

Metals (particularly those in groups 1 and 2) tend to lose the number of electrons that would leave them with the same number of electrons as in the preceding noble gas in the periodic table. By this means, a positively charged ion is formed. Similarly, nonmetals (especially those in groups 16 and 17, and, to a lesser extent, those in Group 15) can gain the number of electrons needed to provide atoms with the same number of electrons as in the next noble gas in the periodic table. Thus, nonmetals tend to form negative ions. Positively charged ions are called cations, and negatively charged ions are called anions. Ions can be either monatomic (containing only one atom) or polyatomic (containing more than one atom).

Compounds that contain ions are called ionic compounds. Ionic compounds generally form from metals and nonmetals. Compounds that do not contain ions, but instead consist of atoms bonded tightly together in molecules (uncharged groups of atoms that behave as a single unit), are called covalent compounds. Covalent compounds usually form from two or more nonmetals.

Chemists use nomenclature rules to clearly name compounds. Ionic and molecular compounds are named using somewhat-different methods. Binary ionic compounds typically consist of a metal and a nonmetal. The name of the metal is written first, followed by the name of the nonmetal with its ending changed to –ide. For example, K2O is called potassium oxide. If the metal can form ions with different charges, a Roman numeral in parentheses follows the name of the metal to specify its charge. Thus, FeCl2 is iron(II) chloride and FeCl3 is iron(III) chloride. Some compounds contain polyatomic ions; the names of common polyatomic ions should be memorized. Molecular compounds can form compounds with different ratios of their elements, so prefixes are used to specify the numbers of atoms of each element in a molecule of the compound. Examples include SF6, sulfur hexafluoride, and N2O4, dinitrogen tetroxide. Acids are an important class of compounds containing hydrogen and having special nomenclature rules. Binary acids are named using the prefix hydro-, changing the –ide suffix to –ic, and adding “acid;” HCl is hydrochloric acid. Oxyacids are named by changing the ending of the anion (-ate to –ic, and -ite to -ous) and adding “acid;” H2CO3 is carbonic acid.

Glossary

- binary acid

- compound that contains hydrogen and one other element, bonded in a way that imparts acidic properties to the compound (ability to release H+ ions when dissolved in water)

- binary compound

- compound containing two different elements.

- covalent bond

- attractive force between the nuclei of a molecule’s atoms and pairs of electrons between the atoms

- covalent compound

- (also, molecular compound) composed of molecules formed by atoms of two or more different elements

- empirical formula

- formula showing the composition of a compound given as the simplest whole-number ratio of atoms

- isomers

- compounds with the same chemical formula but different structures

- ionic bond

- electrostatic forces of attraction between the oppositely charged ions of an ionic compound

- ionic compound

- compound composed of cations and anions combined in ratios, yielding an electrically neutral substance

- molecular compound

- (also, covalent compound) composed of molecules formed by atoms of two or more different elements

- molecular formula

- formula indicating the composition of a molecule of a compound and giving the actual number of atoms of each element in a molecule of the compound.

- monatomic ion

- ion composed of a single atom

- nomenclature

- system of rules for naming objects of interest

- oxyacid

- compound that contains hydrogen, oxygen, and one other element, bonded in a way that imparts acidic properties to the compound (ability to release H+ ions when dissolved in water)

- oxyanion

- polyatomic anion composed of a central atom bonded to oxygen atoms

- polyatomic ion

- ion composed of more than one atom

- spatial isomers

- compounds in which the relative orientations of the atoms in space differ

- structural isomer

- one of two substances that have the same molecular formula but different physical and chemical properties because their atoms are bonded differently

- structural formula

- shows the atoms in a molecule and how they are connected

Contributors and Attributions

Paul Flowers (University of North Carolina - Pembroke), Klaus Theopold (University of Delaware) and Richard Langley (Stephen F. Austin State University) with contributing authors. Textbook content produced by OpenStax College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 license. Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/85abf193-2bd...a7ac8df6@9.110).

Paul Flowers (University of North Carolina - Pembroke), Klaus Theopold (University of Delaware) and Richard Langley (Stephen F. Austin State University) with contributing authors. Textbook content produced by OpenStax College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 license. Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/85abf193-2bd...a7ac8df6@9.110).

Paul Flowers (University of North Carolina - Pembroke), Klaus Theopold (University of Delaware) and Richard Langley (Stephen F. Austin State University) with contributing authors. Textbook content produced by OpenStax College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 license. Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/85abf193-2bd...a7ac8df6@9.110).