Chemistry of Lithium (Z=3)

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 92189

Lithium is a rare element found primarily in molten rock and saltwater in very small amounts. It is understood to be non-vital in human biological processes, although it is used in many drug treatments due to its positive effects on the human brain. Because of its reactive properties, humans have utilized lithium in batteries, nuclear fusion reactions, and thermonuclear weapons.

Introduction

Lithium was first identified as a component of of the mineral petalite and was discovered in 1817 by Johan August Arfwedson, but not isolated until some time later by W.T. Brande and Sir Humphry Davy. In its mineral forms it accounts for only 0.0007% of the earth's crust. It compounds are used in certain kinds of glass and porcelain products. More recently lithium has become important in dry-cell batteries and nuclear reactors. Some compounds of lithium have been used to treat manic depressives.

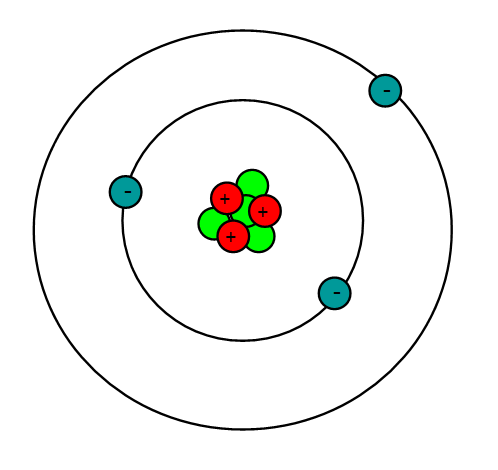

Lithium is an alkali metal with the atomic number = 3 and an atomic mass of 6.941 g/mol. This means that lithium has 3 protons, 3 electrons and 4 neutrons (6.941 - 3 = ~4). Being an alkali metal, lithium is a soft, flammable, and highly reactive metal that tends to form hydroxides. It also has a pretty low density and under standard conditions, it is the least dense solid element.

Properties

Lithium is the lightest of all metals and is named from the Greek work for stone (lithos). It is the first member of the Alkali Metal family. It is less dense than water (with which it reacts) and forms a black oxide in contact with air.

| Atomic Number | 3 |

|---|---|

| Atomic Mass | 6.941 g/mol |

| Atomic Radius | 152 pm |

| Density | 0.534 g/cm3 |

| Color | light silver |

| Melting point | 453.69 K |

| Boiling point | 1615 K |

| Heat of fusion | 3.00 kJ/mol |

| Heat of vaporization | 147.1 kJ/mol |

| Specific heat capacity | 24.860 kJ/mol |

| First ionization energy | 520.2 kJ/mol |

| Oxidation states | +1, -1 |

| Electronegativity | 0.98 |

| Crystal structure | body-centered cubic |

| Magnetism | paramagnetic |

| 2 stable isotopes | 6Li (7.5%) and 7Li (92.5%) |

Periodic Trends of Lithium

Being on the upper left side of the Periodic Table, lithium has a fairly low electronegativity and electron affinity as compared to the rest of the elements. Also, lithium has high metallic character and subsequently lower nonmetallic character when compared with the other elements. Lithium has a higher atomic radius than most of the elements on the Periodic Table. In compounds lithium (like all the alkali metals) has a +1 charge. In its pure form it is soft and silvery white and has a relatively low melting point (181oC).

Reactivity

Lithium is part of the Group 1 Alkali Metals, which are highly reactive and are never found in their pure form in nature. This is due to their electron configuration, in that they have a single valence electron (Figure 1) which is very easily given up in order to create bonds and form compounds.

_↑ ↓_ _↑__

1s2 2s1

Reactions with Water

When placed in contact with water, pure lithium reacts to form lithium hydroxide and hydrogen gas.

\[ 2Li (s) + 2H_2O (l) \rightarrow 2LiOH (aq) + H_2 (g) \nonumber \]

Out of all the group 1 metals, lithium reacts the least violently, slowly releasing the hydrogen gas which may create a bright orange flame only if a substantial amount of lithium is used. This occurs because lithium has the highest activation energy of its group - that is, it takes more energy to remove lithium's one valence electron than with other group 1 elements, because lithium's electron is closer to its nucleus. Atoms with higher activation energies will react slower, although lithium will release more total heat through the entire process.

Reactions with Air

Pure lithium will form lithium hydroxide due to moisture in the air, as well as lithium nitride (\(Li_3N\)) from \(N_2\) gas, and lithium carbonate \((Li_2CO_3\)) from carbon dioxide. These compounds give the normally the silver-white metal a black tarnish. Additionally, it will combust with oxygen as a red flame to form lithium oxide.

\[ 4Li (s) + O_2 (g) \rightarrow 2Li_2O \nonumber \]

Applications

In its mineral forms it accounts for only 0.0007% of the earth's crust. It compounds are used in certain kinds of glass and porcelain products. More recently lithium has become important in dry-cell batteries and nuclear reactors. Some compounds of lithium have been used to treat manic depressives.

Batteries

Lithium is able to be used in the function of a Lithium battery in which the Lithium metal serves as the anode. Lithium ions serve in lithium ion batteries (chargeable) in which the lithium ions move from the negative to positive electrode when discharging, and vice versa when charging.

Heat Transfer

Lithium has the highest specific heat capacity of the solids, Lithium tends to be used as a cooler for heat transfer techniques and applications.

Sources and Extraction

Lithium is most commonly found combined with aluminum, silicon, and oxygen to form the minerals known as spodumene (LiAl(SiO3)2) or petalite/castorite (LiAlSi4O10). These have been found on each of the 6 inhabited continents, but they are mined primarily in Western Australia, China, and Chile. Mineral sources of lithium are becoming less essential, as methods have now been developed to make use of the lithium salts found in saltwater.

Extraction from minerals

The mineral forms of lithium are heated to a high enough temperature (1200 K - 1300 K) in order to crumble them and thus allow for subsequent reactions to more easily take place. After this process, one of three methods can be applied.

- The use of sulfuric acid and sodium carbonate to allow the iron and aluminum to precipitate from the ore - from there, more sodium carbonate is applied to the remaining material allow the lithium to precipitate out, forming lithium carbonate. This is treated with hydrochloric acid to form lithium chloride.

- The use of limestone to calcinate the ore, and then leaching with water, forming lithium hydroxide. Again, this is treated with hydrochloric acid to form lithium chloride.

- The use of sulfuric acid, and then leaching with water, forming lithium sulfate monohydrate. This is treated with sodium carbonate to form lithium carbonate, and then hydrochloric acid to form lithium chloride.

The lithium chloride obtained from any of the three methods undergoes an oxidation-reduction reaction in an electrolytic cell, to separate the chloride ions from the lithium ions. The chloride ions are oxidized, and the lithium ions are reduced.

\[2Cl^- - 2e^- \rightarrow Cl_2 \;\; \text{(oxidation)} \nonumber \]

\[Li^+ + e^- \rightarrow Li \;\; \text{(reduction)} \nonumber \]

Extraction from Saltwater

Saltwater naturally contains lithium chloride, which must be extracted in the form of lithium carbonate, then it is re-treated, separated into its ions, and reduced in the same electrolytic process as in extraction from lithium ores. Only three saltwater lakes in the world are currently used for lithium extraction, in Nevada, Chile, and Argentina.

Saltwater is channeled into shallow ponds and over a period of a year or more, water evaporates out to leave behind various salts. Lime is used to remove the magnesium salt, so that the remaining solution contains a fairly concentrated amount of lithium chloride. The solution is then treated with sodium carbonate in order for usable lithium carbonate to precipitate out.

References

- Kipouros, Georges J and Sadoway, Donald R. "Toward New Technologies for the Production of Lithium." Journal of Metals. The Minerals, Metals, & Materials Society. Volume 50, No. 5 May 1998: 24-32.

- Shin, Y. J. ; Kim, I. S. ; Oh, S. C. ; Park, C. K. and Lee, C. S. "Lithium Recovery from Radioactive Molten Salt Wastes by Electrolysis." Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry. Akadémiai Kiadó and Springer Science+Business Media B.V. Volume 243, No. 3 March 2000: 639-643.

- Tahil, William. "The Trouble with Lithium - Implications of Future PHEV Production for Lithium Demand." Meridian International Research. January 2007.

Outside Links

- http://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Lithium

- http://intelegen.com/nutrients/lithium.htm

- www.scribd.com/doc/11579770/Extraction-Properties-and-Uses-of-Lithium

Problems

- With which group of elements will lithium form compounds the most easily with?

- What is the electron configuration of Li+?

- What are some common uses of lithium?

- For a lithium-ion battery containing LiCoO2, should the compound be placed in the anode or cathode?

- Given that 7Li is 7.0160 amu and 6Li is 6.0151 amu, and their percent abundance is 92.58% and 7.42% respectively, what is the atomic mass of lithium?

Solutions

- Group 17 Halogens (lithium forms strongly inic bonds with them, as halogens are highly electronegative and lithium has a free electron)

- 1s2

- Lithium-ion batteries, disposable lithium batteries, pyrotechnics, creation of strong metal alloys, etc.

- Anode - lithium is oxidized (LiCoO2 → Li+ + CoO2)

- 6.942 g/mol

Contributors and Attributions

- Katherine Szelong (UCD), Kevin Fan