20.4: Amines and Amides

- Page ID

- 414750

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the structure and properties of an amine

- Describe the structure and properties of an amide

Amines are molecules that contain carbon-nitrogen bonds. The nitrogen atom in an amine has a lone pair of electrons and three bonds to other atoms, either carbon or hydrogen. Various nomenclatures are used to derive names for amines, but all involve the class-identifying suffix –ine as illustrated here for a few simple examples:

In some amines, the nitrogen atom replaces a carbon atom in an aromatic hydrocarbon. Pyridine (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)) is one such heterocyclic amine. A heterocyclic compound contains atoms of two or more different elements in its ring structure.

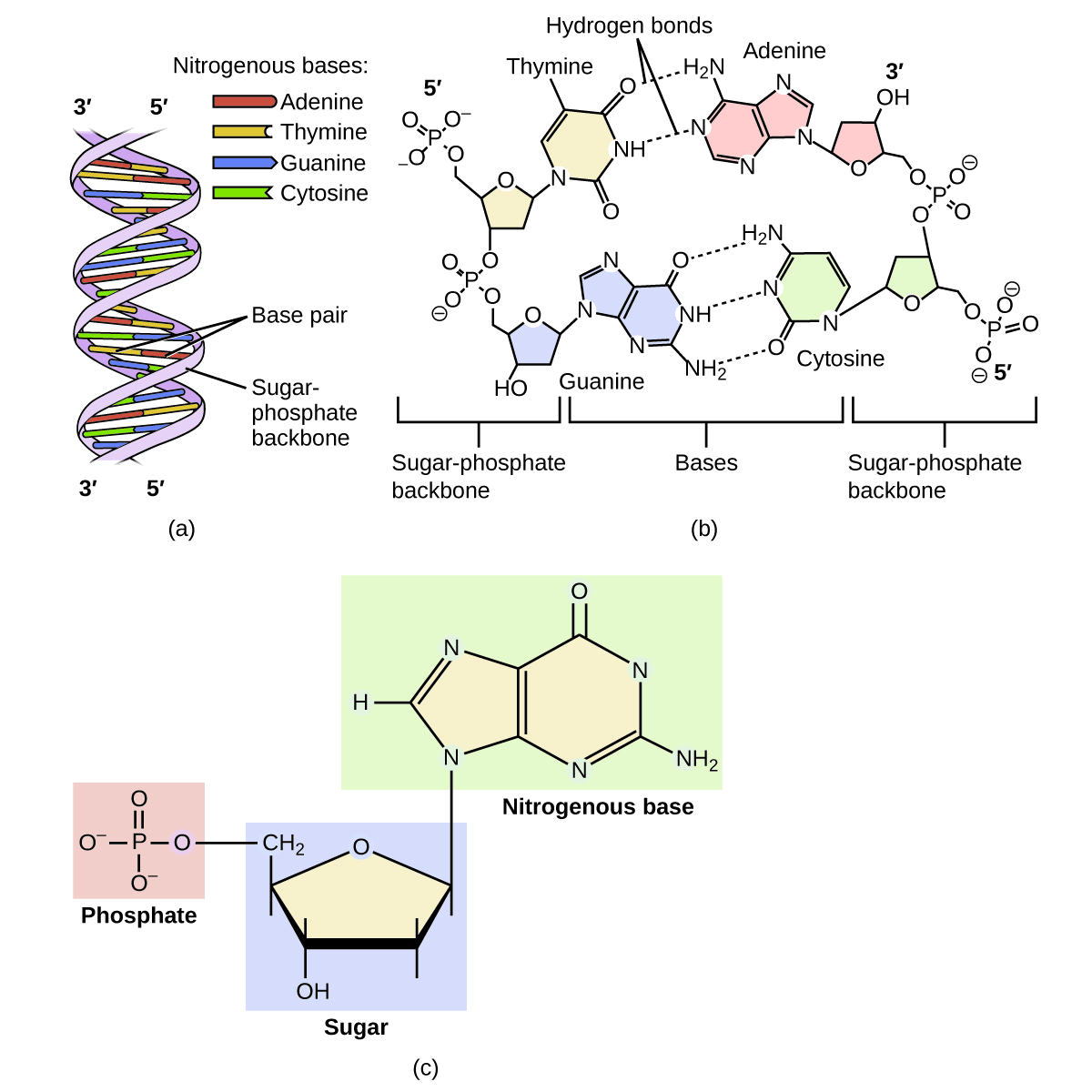

The genetic material for all living things is a polymer of four different molecules, which are themselves a combination of three subunits. The genetic information, the code for developing an organism, is contained in the specific sequence of the four molecules, similar to the way the letters of the alphabet can be sequenced to form words that convey information. The information in a DNA sequence is used to form two other types of polymers, one of which are proteins. The proteins interact to form a specific type of organism with individual characteristics.

A genetic molecule is called DNA, which stands for deoxyribonucleic acid. The four molecules that make up DNA are called nucleotides. Each nucleotide consists of a single- or double-ringed molecule containing nitrogen, carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen called a nitrogenous base. Each base is bonded to a five-carbon sugar called deoxyribose. The sugar is in turn bonded to a phosphate group

It probably makes sense that the sequence of nucleotides in the DNA of a cat differs from those of a dog. But it is also true that the sequences of the DNA in the cells of two individual pugs differ. Likewise, the sequences of DNA in you and a sibling differ (unless your sibling is an identical twin), as do those between you and an unrelated individual. However, the DNA sequences of two related individuals are more similar than the sequences of two unrelated individuals, and these similarities in sequence can be observed in various ways. This is the principle behind DNA fingerprinting, which is a method used to determine whether two DNA samples came from related (or the same) individuals or unrelated individuals.

Using similarities in sequences, technicians can determine whether a man is the father of a child (the identity of the mother is rarely in doubt, except in the case of an adopted child and a potential birth mother). Likewise, forensic geneticists can determine whether a crime scene sample of human tissue, such as blood or skin cells, contains DNA that matches exactly the DNA of a suspect.

Watch this video animation of how DNA is packaged for a visual lesson in its structure.

Like ammonia, amines are weak bases due to the lone pair of electrons on their nitrogen atoms:

The basicity of an amine’s nitrogen atom plays an important role in much of the compound’s chemistry. Amine functional groups are found in a wide variety of compounds, including natural and synthetic dyes, polymers, vitamins, and medications such as penicillin and codeine. They are also found in many molecules essential to life, such as amino acids, hormones, neurotransmitters, and DNA.

Since ancient times, plants have been used for medicinal purposes. One class of substances, called alkaloids, found in many of these plants has been isolated and found to contain cyclic molecules with an amine functional group. These amines are bases. They can react with H3O+ in a dilute acid to form an ammonium salt, and this property is used to extract them from the plant:

The name alkaloid means “like an alkali.” Thus, an alkaloid reacts with acid. The free compound can be recovered after extraction by reaction with a base:

The structures of many naturally occurring alkaloids have profound physiological and psychotropic effects in humans. Examples of these drugs include nicotine, morphine, codeine, and heroin. The plant produces these substances, collectively called secondary plant compounds, as chemical defenses against the numerous pests that attempt to feed on the plant:

In these diagrams, as is common in representing structures of large organic compounds, carbon atoms in the rings and the hydrogen atoms bonded to them have been omitted for clarity. The solid wedges indicate bonds that extend out of the page. The dashed wedges indicate bonds that extend into the page. Notice that small changes to a part of the molecule change the properties of morphine, codeine, and heroin. Morphine, a strong narcotic used to relieve pain, contains two hydroxyl functional groups, located at the bottom of the molecule in this structural formula. Changing one of these hydroxyl groups to a methyl ether group forms codeine, a less potent drug used as a local anesthetic. If both hydroxyl groups are converted to esters of acetic acid, the powerfully addictive drug heroin results (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)).

Amides are molecules that contain nitrogen atoms connected to the carbon atom of a carbonyl group. Like amines, various nomenclature rules may be used to name amides, but all include use of the class-specific suffix -amide:

Amides can be produced when carboxylic acids react with amines or ammonia in a process called amidation. A water molecule is eliminated from the reaction, and the amide is formed from the remaining pieces of the carboxylic acid and the amine (note the similarity to formation of an ester from a carboxylic acid and an alcohol discussed in the previous section):

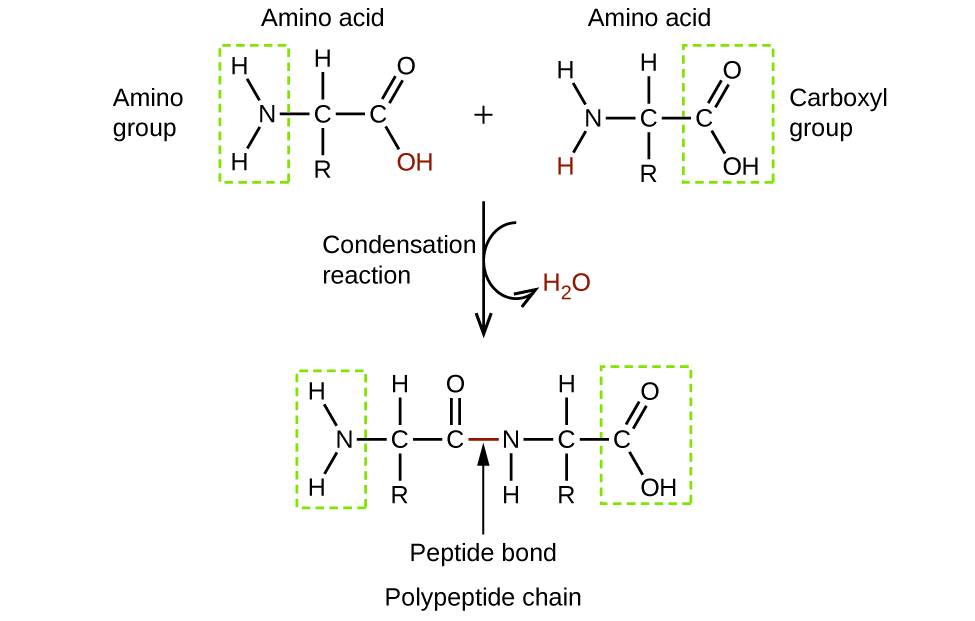

The reaction between amines and carboxylic acids to form amides is biologically important. It is through this reaction that amino acids (molecules containing both amine and carboxylic acid substituents) link together in a polymer to form proteins.

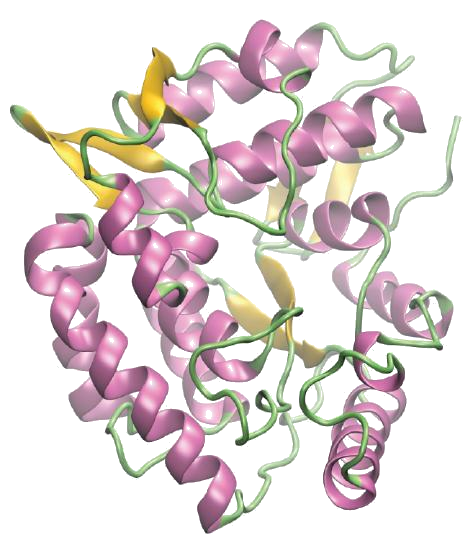

Proteins are large biological molecules made up of long chains of smaller molecules called amino acids. Organisms rely on proteins for a variety of functions—proteins transport molecules across cell membranes, replicate DNA, and catalyze metabolic reactions, to name only a few of their functions. The properties of proteins are functions of the combination of amino acids that compose them and can vary greatly. Interactions between amino acid sequences in the chains of proteins result in the folding of the chain into specific, three-dimensional structures that determine the protein’s activity.

Amino acids are organic molecules that contain an amine functional group (–NH2), a carboxylic acid functional group (–COOH), and a side chain (that is specific to each individual amino acid). Most living things build proteins from the same 20 different amino acids. Amino acids connect by the formation of a peptide bond, which is a covalent bond formed between two amino acids when the carboxylic acid group of one amino acid reacts with the amine group of the other amino acid. The formation of the bond results in the production of a molecule of water (in general, reactions that result in the production of water when two other molecules combine are referred to as condensation reactions). The resulting bond—between the carbonyl group carbon atom and the amine nitrogen atom is called a peptide link or peptide bond. Since each of the original amino acids has an unreacted group (one has an unreacted amine and the other an unreacted carboxylic acid), more peptide bonds can form to other amino acids, extending the structure. (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)) A chain of connected amino acids is called a polypeptide. Proteins contain at least one long polypeptide chain.

Enzymes are large biological molecules, mostly composed of proteins, which are responsible for the thousands of metabolic processes that occur in living organisms. Enzymes are highly specific catalysts; they speed up the rates of certain reactions. Enzymes function by lowering the activation energy of the reaction they are catalyzing, which can dramatically increase the rate of the reaction. Most reactions catalyzed by enzymes have rates that are millions of times faster than the noncatalyzed version. Like all catalysts, enzymes are not consumed during the reactions that they catalyze. Enzymes do differ from other catalysts in how specific they are for their substrates (the molecules that an enzyme will convert into a different product). Each enzyme is only capable of speeding up one or a few very specific reactions or types of reactions. Since the function of enzymes is so specific, the lack or malfunctioning of an enzyme can lead to serious health consequences. One disease that is the result of an enzyme malfunction is phenylketonuria. In this disease, the enzyme that catalyzes the first step in the degradation of the amino acid phenylalanine is not functional (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)). Untreated, this can lead to an accumulation of phenylalanine, which can lead to intellectual disabilities.

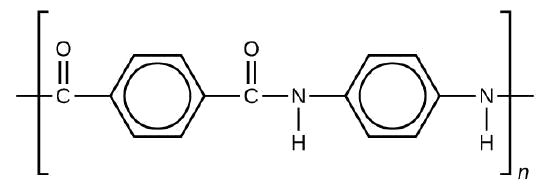

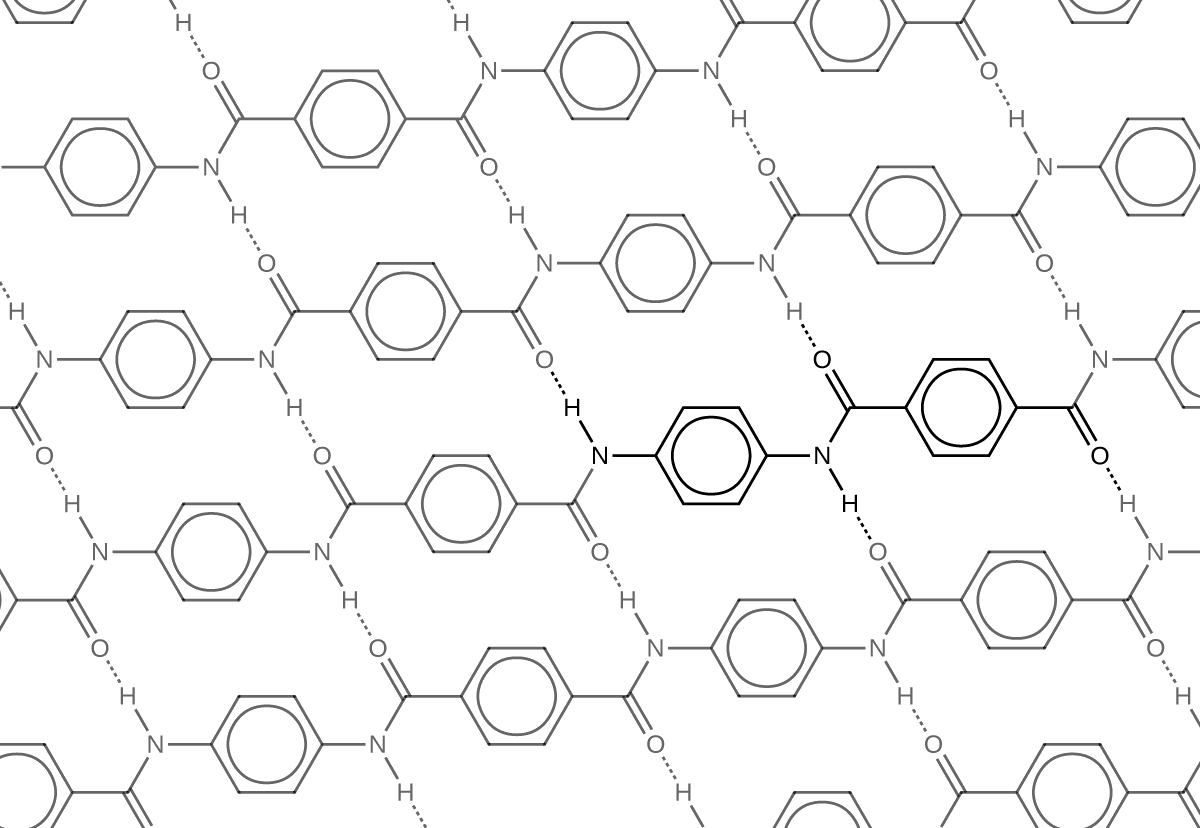

Kevlar (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)) is a synthetic polymer made from two monomers 1,4-phenylene-diamine and terephthaloyl chloride (Kevlar is a registered trademark of DuPont). The material was developed by Susan Kwolek while she worked to find a replacement for steel in tires. Kwolek's work involved synthesizing polyamides and dissolving them in solvents, then spinning the resulting solution into fibers. One of her solutions proved to be quite different in initial appearance and structure. And once spun, the resulting fibers were particularly strong. From this initial discovery, Kevlar was created. The material has a high tensile strength-to-weight ratio (it is about 5 times stronger than an equal weight of steel), making it useful for many applications from bicycle tires to sails to body armor.

The material owes much of its strength to hydrogen bonds between polymer chains (refer back to the chapter on intermolecular interactions). These bonds form between the carbonyl group oxygen atom (which has a partial negative charge due to oxygen’s electronegativity) on one monomer and the partially positively charged hydrogen atom in the N–H bond of an adjacent monomer in the polymer structure (see dashed lines in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)). There is additional strength derived from the interaction between the unhybridized p orbitals in the six-membered rings, called aromatic stacking.

Kevlar may be best known as a component of body armor, combat helmets, and face masks. Since the 1980s, the US military has used Kevlar as a component of the PASGT (personal armor system for ground troops) helmet and vest. Kevlar is also used to protect armored fighting vehicles and aircraft carriers. Civilian applications include protective gear for emergency service personnel such as body armor for police officers and heat-resistant clothing for fire fighters. Kevlar based clothing is considerably lighter and thinner than equivalent gear made from other materials (Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)). Beyond Kevlar, Susan Kwolek was instrumental in the development of Nomex, a fireproof material, and was also involved in the creation of Lycra. She became just the fourth woman inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame, and received a number of other awards for her significant contributions to science and society.

In addition to its better-known uses, Kevlar is also often used in cryogenics for its very low thermal conductivity (along with its high strength). Kevlar maintains its high strength when cooled to the temperature of liquid nitrogen (–196 °C).

The table here summarizes the structures discussed in this chapter: