3.4: Supercritical Fluid Chromatography

- Page ID

- 55866

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)A popular and powerful tool in the chemical world, chromatography separates mixtures based on chemical properties – even some than were previously thought inseparable. It combines a multitude of pieces, concepts, and chemicals to form an instrument suited to specific separation. One form of chromatography that is often overlooked is that of supercritical fluid chromatography.

History

Supercritical fluid chromatography (SFC) begins its history in 1962 under the name “high pressure gas chromatography”. It started off slow and was quickly overshadowed by the development of high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and the already developed gas chromatography. SFC was not a popular method of chromatography until the late 1980s, when more publications began exemplifying its uses and techniques.

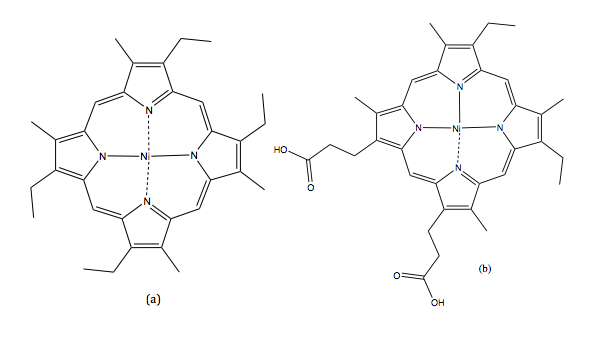

SFC was first reported by Klesper et al. They succeeded in separating thermally labile porphyrin mixtures on polyethylene glycol stationary phase with two mobile phase units: dichlorodifluoromethane (CCl2F2) and monochlorodifluoromethane (CHCl2F), as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\). Their results proved that supercritical fluids’ low viscosity but high diffusivity functions well as a mobile phase.

After Klesper’s paper detailing his separation procedure, subsequent scientists aimed to find the perfect mobile phase and the possible uses for SFC. Using gases such as He, N2, CO2, and NH3, they examined purines, nucleotides, steroids, sugars, terpenes, amino acids, proteins, and many more substances for their retention behavior. They discovered that CO2 was an ideal supercritical fluid due to its low critical temperature of 31 °C and relatively low critical pressure of 72.8 atm. Extra advantages of CO2 included it being cheap, non-flammable, and non-toxic. CO2 is now the standard mobile phase for SFC.

In the development of SFC over the years, the technique underwent multiple trial-and-error phases. Open tubular capillary column SFC had the advantage of independently and cooperatively changing all three parameters (pressure, temperature, and modifier content) to a certain extent. Like any chromatography method, however, it had its drawbacks. Changing the pressure, the most important parameter, often required changing the flow velocity due to the constant diameter of the capillaries. Additionally, CO2, the ideal mobile phase, is non-polar, and its polarity could not be altered easily or with a gradient.

Over the years, many uses were discovered for SFC. It was identified as a useful tool in the separation of chiral compounds, drugs, natural products, and organometallics (see below for more detail). Most SFCs currently are involved a silica (or silica + modifier) packed column with a CO2 (or CO2 + modifier) mobile phase. Mass spectrometry is the most common tool used to analyze the separated samples.

Supercritical Fluids

What is a Supercritical Fluid?

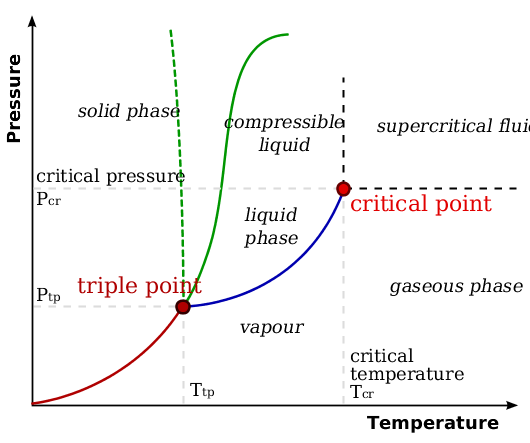

As mentioned previously, the advantage to supercritical fluids is the combination of the useful properties from two phases: liquids and gases. Supercritical fluids are gas-like in the ways of expanding to fill a given volume, and the motions of the particles are close to that of a gas. On the side of liquid properties, supercritical fluids have densities near that of liquids and thus dissolve and interact with other particles, as you would expect of a liquid. To visualize phase changes in relation to pressure and temperature, phase diagrams are used as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) shows the stark differences between two phases in relation to the surrounding conditions. There exist two ambiguous regions. One of these is the point at which all three lines intersect: the triple point. This is the temperature and pressure at which all three states can exist in a dynamic equilibrium. The second ambiguous point comes at the end of the liquid/gas line, where it just ends. At this temperature and pressure, the pure substance has reached a point where it will no longer exist as just one phase or the other: it exists as a hybrid phase – a liquid and gas dynamic equilibrium.

Unique Properties of Supercritical Fluids

As a result of the dynamic liquid-gas equilibrium, supercritical fluids possess three unique qualities: increased density (on the scale of a liquid), increased diffusivity (similar to that of a gas), and lowered viscosity (on the scale of a gas). Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) shows the similarities in each of these properties. Remember, each of these explains a part of why SFC is an advantageous method of chemical separation.

| Density (g/mL) | Diffusivity (cm2/s) | Dynamic Viscosity (g/cm s) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gas | 1 x 10-3 | 1 x 10-1 | 1 x 10-2 |

| Liquid | 1.0 | 5 x 10-6 | 1 x 10-4 |

| Supercritical Fluid | 3 x 10-1 | 1 x 10-3 | 1 x 10-2 |

Applying the Properties of Supercritical Fluids to Chromatography

How are these properties useful? An ideal mobile phase and solvent will do three things well: interact with other particles, carry the sample through the column, and quickly (but accurately) elute it.

Density, as a concept, is simple: the denser something is, the more likely that it will interact with particles it moves through. Affected by an increase in pressure (given constant temperature), density is largely affected by a substance entering the supercritical fluid zone. Supercritical fluids are characterized with densities comparable to those of liquids, meaning they have a better dissolving effect and act as a better carrier gas. High densities among supercritical fluids are imperative for both their effect as solvents and their effect as carrier gases.

Diffusivity refers to how fast the substance can spread among a volume. With increased pressure comes decreased diffusivity (an inverse relationship) but with increased temperature comes increased diffusivity (a direct relationship related to their kinetic energy). Because supercritical fluids have diffusivity values between a gas and liquid, they carry the advantage of a liquid’s density, but the diffusivity closer to that of a gas. Because of this, they can quickly carry and elute a sample, making for an efficient mobile phase.

Finally, dynamic viscosity can be viewed as the resistance to other components flowing through, or intercalating themselves, in the supercritical fluid. Dynamic viscosity is hardly affected by temperature or pressure for liquids, whereas it can be greatly affected for supercritical fluids. With the ability to alter dynamic viscosity through temperature and pressure, the operator can determine how resistant their supercritical fluid should be.

Supercritical Properties of CO2

Because of its widespread use in SFC, it’s important to discuss what makes CO2 an ideal supercritical fluid. One of the biggest limitations to most mobile phases in SFC is getting them to reach the critical point. This means extremely high temperatures and pressures, which is not easily attainable. The best gases for this are ones that can achieve a critical point at relatively low temperatures and pressures.

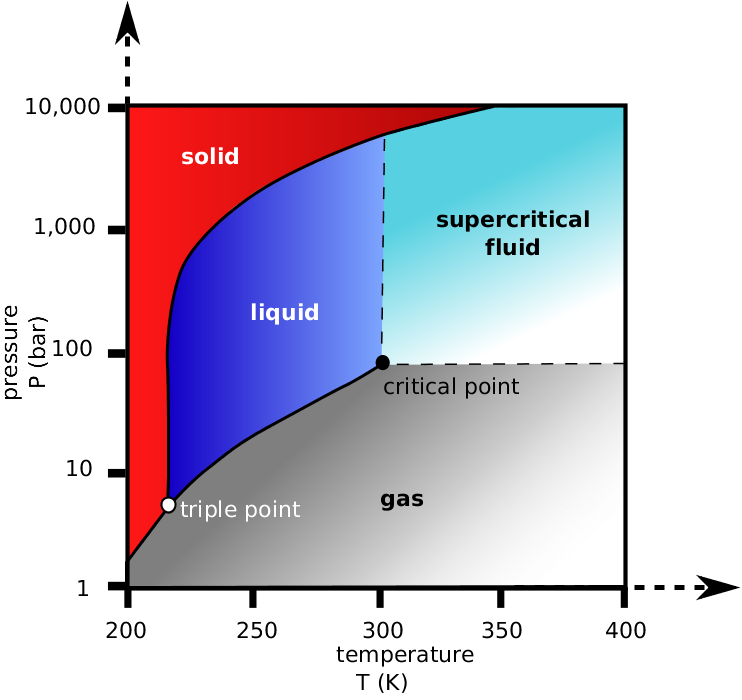

As seen from Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\), CO2 has a critical temperature of approximately 31 °C and a critical pressure of around 73 atm. These are both relatively low numbers and are thus ideal for SFC. Of course, with every upside there exists a downside. In this case, CO2 lacks polarity, which makes it difficult to use its mobile phase properties to elute polar samples. This is readily fixed with a modifier, which will be discussed later.

The Instrument

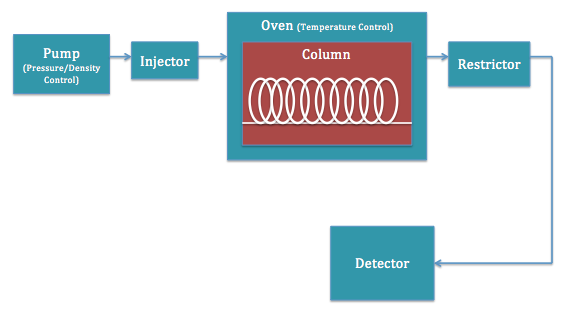

SFC has a similar instrument setup to most other chromatography machines, notably HPLC. The functions of the parts are very similar, but it is important to understand them for the purposes of understanding the technique. Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) shows a schematic representation of a typical apparatus.

Columns

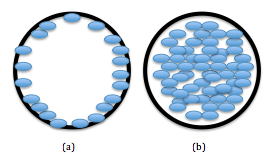

There are two main types of columns used with SFC: open tubular and packed, as seen below. The columns themselves are near identical to HPLC columns in terms of material and coatings. Open tubular columns are most used and are coated with a cross-linked silica material (powdered quartz, SiO2) for a stationary phase. Column lengths range, but usually fall between 10 and 20 meters and are coated with less than 1 µm of silica stationary phase. Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\) demonstrates the differences in the packing of the two columns.

Injector

Injectors act as the main site for the insertion of samples. There are many different kinds of injectors that depend on a multitude of factors. For packed columns, the sample must be small and the exact amount depends on the column diameter. For open tubular columns, larger volumes can be used. In both cases, there are specific injectors that are used depending on how the sample needs to be placed in the instrument. A loop injector is used mainly for preliminary testing. The sample is fed into a chamber that is then flushed with the supercritical fluid and pushed down the column. It uses a low-pressure pump before proceeding with the full elution at higher pressures. An inline injector allows for easy control of sample volume. A high-pressure pump forces the (specifically measured) sample into a stream of eluent, which proceeds to carry the sample through the column. This method allows for specific dilutions and greater flexibility. For samples requiring no dilution or immediate interaction with the eluent, an in-column injector is useful. This allows the sample to be transferred directly into the packed column and the mobile phase to then pass through the column.

Pump

The existence of a supercritical fluid, as discussed previously, depends on high temperatures and high pressures. The pump is responsible for delivering the high pressures. By pressurizing the gas (or liquid), it can cause the substance to become dense enough to exhibit signs of the desired supercritical fluid. Because pressure couples with heat to create the supercritical fluid, the two are usually very close together on the instrument.

Oven

The oven, as referenced before, exists to heat the mobile phase to its desired temperature. In the case of SFC, the desired temperature is always the critical temperature of the supercritical fluid. These ovens are precisely controlled and standard across SFC, HPLC, and GC.

Detector

So far, there has been one largely overlooked component of the SFC machine: the detector. Technically not a part of the chromatographic separation process, the detector still plays an important role: identifying the components of the solution. While the SFC aims to separate components with good resolution (high purity, no other components mixed in), the detector aims to define what each of these components is made of.

The two detectors most often found on SFC instruments are either flame ionization detectors (FID) or mass spectrometers (MS):

- FIDs operate through ionizing the sample in a hydrogen-powered flame. By doing so, they produce charged particles, which hit electrodes, and the particles are subsequently quantified and identified.

- MS operates through creating an ionized spray of the sample, and then separating the ions based on a mass/charge ratio. The mass/charge ratio is plotted against ion abundance and creates a “fingerprint” for the chemical identified. This chemical fingerprint is then matched against a database to isolate which compound it was. This can be done for each unique elution, rendering the SFC even more useful than if it were standing alone.

Sample

Generally speaking, samples need little preparation. The only major requirement is that it dissolves in a solvent less polar than methanol: it must have a dielectric constant lower than 33, since CO2 has a low polarity and cannot easily elute polar samples. To combat this, modifiers are added to the mobile phase.

Stationary Phase

The stationary phase is a neutral compound that acts as a source of “friction” for certain molecules in the sample as they slide through the column. Silica attracts polar molecules and thus the molecules attach strongly, holding until enough of the mobile phase has passed through to attract them away. The combination of the properties in the stationary phase and the mobile phase help determine the resolution and speed of the experiment.

Mobile Phase

The mobile phase (the supercritical fluid) pushes the sample through the column and elutes separate, pure, samples. This is where the supercritical fluid’s properties of high density, high diffusivity, and low viscosity come into play. With these three properties, the mobile phase is able to adequately interact with the sample, quickly push through it, and strongly plow through the sample to separate it out. The mobile phase also partly determines how it separates out: it will first carry out similar molecules, ones with similar polarities, and follow gradually with molecules with larger polarities.

Modifiers

Modifiers are added to the mobile phase to play with its properties. As mentioned a few times previously, CO2supercritical fluid lacks polarity. In order to add polarity to the fluid (without causing reactivity), a polar modifier will often be added. Modifiers usually raise the critical pressure and temperature of the mobile phase a little, but in return add polarity to the phase and result in a fully resolved sample. Unfortunately, with too much modifier, higher temperatures and pressures are needed and reactivity increases (which is dangerous and bad for the operator). Modifiers, such as ethanol or methanol, are used in small amounts as needed for the mobile phase in order to create a more polar fluid.

Advantages of Supercritical Fluid Chromatography

Clearly, SFC possesses some extraordinary potential as far as chromatography techniques go. It has some incredible capabilities that allow efficient and accurate resolution of mixtures. Below is a summary of its advantages and disadvantages stacked against other conventional (competing) chromatography methods.

Advantages over HPLC

- Because supercritical fluids have low viscosities the analysis is faster, there is a much lower pressure drop across the column, and open tubular columns can be used.

- Shorter column lengths are needed (10-20 m for SFC versus 15-60 m for HPLC) due to the high diffusivity of the supercritical fluid. More interactions can occur in a shorter span of time/distance.

- Resolving power is much greater (5x) than HPLC due to the high diffusivity of the supercritical fluid. More interactions result in better separation of the components in a shorter amount of time.

Advantages over GC

- Able to analyze many solutes with no derivatization since there is no need to convert most polar groups into nonpolar ones.

- Can analyze thermally labile compounds more easily with high resolution since it can provide faster analysis at lower temperatures.

- Can analyze solutes with high molecular weight due to their greater solubizing power.

General Disadvantages

- Cannot analyze extremely polar solutes due to relatively nonpolar mobile phase, CO2.

Applications

While the use of SFC has been mainly organic-oriented, there are still a few ways that inorganic compound mixtures are separated using the method. The two main ones, separation of chiral compounds (mainly metal-ligand complexes) and organometallics are discussed here.

Chiral Compounds

For chiral molecules, the procedures and choice of column in SFC are very similar to those used in HPLC. Packed with cellulose type chiral stationary phase (or some other chiral stationary phase), the sample flows through the chiral compound and only molecules with a matching chirality will stick to the column. By running a pure CO2 supercritical fluid mobile phase, the non-sticking enantiomer will elute first, followed eventually (but slowly) with the other one.

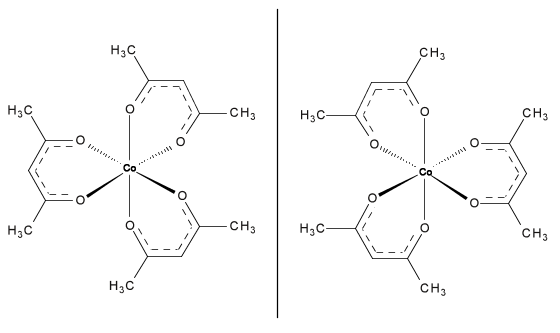

In the field of inorganic chemistry, a racemic mixture of Co(acac)3, both isomers shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\) has been resolved using a cellulose-based chiral stationary phase. The SFC method was one of the best and most efficient instruments in analyzing the chiral compound. While SFC easily separates coordinate covalent compounds, it is not necessary to use such an extensive instrument to separate mixtures of it since there are many simpler techniques.

Organometallics

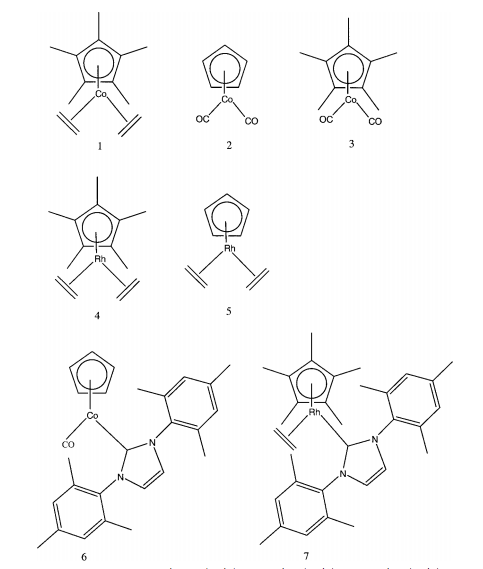

Many d-block organometallics are highly reactive and easily decompose in air. SFC offers a way to chromatograph mixtures of large, unusual organometallic compounds. Large cobalt and rhodium based organometallic compound mixtures have been separated using SFC (Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\) ) without exposing the compounds to air.

By using a stationary phase of siloxanes, oxygen-linked silicon particles with different substituents attached, the organometallics were resolved based on size and charge. Thanks to the non-polar, highly diffusive, and high viscosity properties of a 100% CO2 supercritical fluid, the mixture was resolved and analyzed with a flame ionization detector. It was determined that the method was sensitive enough to detect impurities of 1%. Because the efficiency of SFC is so impressive, the potential for it in the organometallic field is huge. Identifying impurities down to 1% shows promise for not only preliminary data in experiments, but quality control as well.

Conclusion

While it may have its drawbacks, SFC remains an untapped resource in the ways of chromatography. The advantages to using supercritical fluids as mobile phases demonstrate how resolution can be increased without sacrificing time or increasing column length. Nonetheless, it is still a well-utilized resource in the organic, biomedical, and pharmaceutical industries. SFC shows promise as a reliable way of separating and analyzing mixtures.