3.3: Basic Principles of Supercritical Fluid Chromatography and Supercrtical Fluid Extraction

- Page ID

- 55864

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The discovery of supercritical fluids led to novel analytical applications in the fields of chromatography and extraction known as supercritical fluid chromatography (SFC) and supercritical fluid extraction (SFE). Supercritical fluid chromatography is accepted as a column chromatography methods along with gas chromatography (GC) and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Due to to the properties of supercritical fluids, SFC combines each of the advantages of both GC and HPLC in one method. In addition, supercritical fluid extraction is an advanced analytical technique.

Definition and Formation of Supercritical Fluids

A supercritical fluid is the phase of a material at critical temperature and critical pressure of the material. Critical temperature is the temperature at which a gas cannot become liquid as long as there is no extra pressure; and, critical pressure is the minimum amount of pressure to liquefy a gas at its critical temperature. Supercritical fluids combine useful properties of gas and liquid phases, as it can behave like both a gas and a liquid in terms of different aspects. A supercritical fluid provides a gas-like characteristic when it fills a container and it takes the shape of the container. The motion of the molecules are quite similar to gas molecules. On the other hand, a supercritical fluid behaves like a liquid because its density property is near liquid and, thus, a supercritical fluid shows a similarity to the dissolving effect of a liquid.

The characteristic properties of a supercritical fluid are density, diffusivity and viscosity. Supercritical values for these features take place between liquids and gases. Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) demonstrates numerical values of properties for gas, supercritical fluid and liquid.

| Gas | Supercritical fluid | Liquid | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density (g/cm3) | 0.6 x 10-3-2.0 x 10-3 | 0.2-0.5 | 0.6-2.0 |

| Diffusivity (cm2/s) | 0.1-0.4 | 10-3-10-4 | 0.2 x 10-5-2.0 x 10-5 |

| Viscosity (cm/s) | 1 x 10-4-3 x 10-4 | 1 x 10-4-3 x 10-4 | 0.2 x 10-2-3.0 x 10-2 |

The formation of a supercritical fluid is the result of a dynamic equilibrium. When a material is heated to its specific critical temperature in a closed system, at constant pressure, a dynamic equilibrium is generated. This equilibrium includes the same number of molecules coming out of liquid phase to gas phase by gaining energy and going in to liquid phase from gas phase by losing energy. At this particular point, the phase curve between liquid and gas phases disappears and supercritical material appears.

In order to understand the definition of SF better, a simple phase diagram can be used. Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) displays an ideal phase diagram. For a pure material, a phase diagram shows the fields where the material is in the form of solid, liquid, and gas in terms of different temperature and pressure values. Curves, where two phases (solid-gas, solid-liquid and liquid-gas) exist together, defines the boundaries of the phase regions. These curves, for example, include sublimation for solid-gas boundary, melting for solid-liquid boundary, and vaporization for liquid-gas boundary. Other than these binary existence curves, there is a point where all three phases are present together in equilibrium; the triple point (TP).

There is another characteristic point in the phase diagram, the critical point (CP). This point is obtained at critical temperature (Tc) and critical pressure (Pc). After the CP, no matter how much pressure or temperature is increased, the material cannot transform from gas to liquid or from liquid to gas phase. This form is the supercritical fluid form. Increasing temperature cannot result in turning to gas, and increasing pressure cannot result in turning to liquid at this point. In the phase diagram, the field above Tc and Pc values is defined as the supercritical region.

In theory, the supercritical region can be reached in two ways:

- Increasing the pressure above the Pc value of the material while keeping the temperature stable and then increasing the temperature above Tc value at a stable pressure value.

- Increasing the temperature first above Tc value and then increasing the pressure above Pc value.

The critical point is characteristic for each material, resulting from the characteristic Tc and Pc values for each substance.

Physical Properties of Supercritical Fluids

As mentioned above, SF shares some common features with both gases and liquids. This enables us to take advantage of a correct combination of the properties.

Density

Density characteristic of a supercritical fluid is between that of a gas and a liquid, but closer to that of a liquid. In the supercritical region, density of a supercritical fluid increases with increased pressure (at constant temperature). When pressure is constant, density of the material decreases with increasing temperature. The dissolving effect of a supercritical fluid is dependent on its density value. Supercritical fluids are also better carriers than gases thanks to their higher density. Therefore, density is an essential parameter for analytical techniques using supercritical fluids as solvents.

Diffusivity

Diffusivity of a supercritical fluid can be 100 x that of a liquid and 1/1,000 to 1/10,000 x less than a gas. Because supercritical fluids have more diffusivity than a liquid, it stands to reason a solute can show better diffusivity in a supercritical fluid than in a liquid. Diffusivity is parallel with temperature and contrary with pressure. Increasing pressure affects supercritical fluid molecules to become closer to each other and decreases diffusivity in the material. The greater diffusivity gives supercritical fluids the chance to be faster carriers for analytical applications. Hence, supercritical fluids play an important role for chromatography and extraction methods.

Viscosity

Viscosity for a supercritical fluid is almost the same as a gas, being approximately 1/10 of that of a liquid. Thus, supercritical fluids are less resistant than liquids towards components flowing through. The viscosity of supercritical fluids is also distinguished from that of liquids in that temperature has a little effect on liquid viscosity, where it can dramatically influence supercritical fluid viscosity.

These properties of viscosity, diffusivity, and density are related to each other. The change in temperature and pressure can affect all of them in different combinations. For instance, increasing pressure causes a rise for viscosity and rising viscosity results in declining diffusivity.

Super Fluid Chromatography (SFC)

Just like supercritical fluids combine the benefits of liquids and gases, SFC bring the advantages and strong aspects of HPLC and GC together. SFC can be more advantageous than HPLC and GC when compounds which decompose at high temperatures with GC and do not have functional groups to be detected by HPLC detection systems are analyzed.

There are three major qualities for column chromatographies:

- Selectivity.

- Efficiency.

- Sensitivity.

Generally, HPLC has better selectivity that SFC owing to changeable mobile phases (especially during a particular experimental run) and a wide range of stationary phases. Although SFC does not have the selectivity of HPLC, it has good quality in terms of sensitivity and efficiency. SFC enables change of some properties during the chromatographic process. This tuning ability allows the optimization of the analysis. Also, SFC has a broader range of detectors than HPLC. SFC surpasses GC for the analysis of easily decomposable substances; these materials can be used with SFC due to its ability to work with lower temperatures than GC.

Instrumentation for SFC

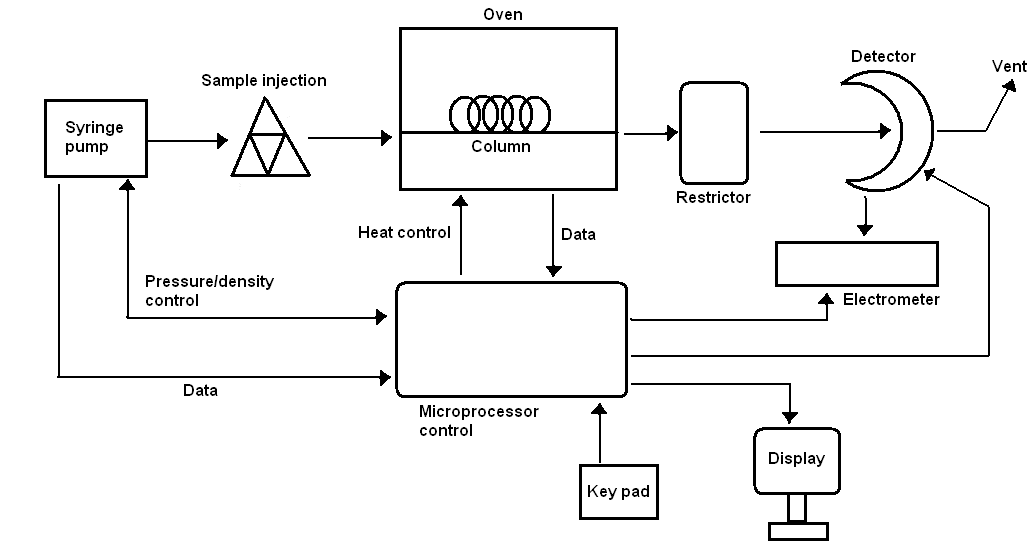

As it can be seen in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) SFC has a similar setup to an HPLC instrument. They use similar stationary phases with similar column types. However, there are some differences. Temperature is critical for supercritical fluids, so there should be a heat control tool in the system similar to that of GC. Also, there should be a pressure control mechanism, a restrictor, because pressure is another essential parameter in order for supercritical fluid materials to be kept at the required level. A microprocessor mechanism is placed in the instrument for SFC. This unit collects data for pressure, oven temperature, and detector performance to control the related pieces of the instrument.

Stationary Phase

SFC columns are similar to HPLC columns in terms of coating materials. Open-tubular columns and packed columns are the two most common types used in SFC. Open-tubular ones are preferred and they have similarities to HPLC fused-silica columns. This type of column contains an internal coating of a cross-linked siloxane material as a stationary phase. The thickness of the coating can be 0.05-1.0 μm. The length of the column can range from of 10 to 20 m.

Mobile Phases

There is a wide variety of materials used as mobile phase in SFC. The mobile phase can be selected from the solvent groups of inorganic solvents, hydrocarbons, alcohols, ethers, halides; or can be acetone, acetonitrile, pyridine, etc. The most common supercritical fluid which is used in SFC is carbon dioxide because its critical temperature and pressure are easy to reach. Additionally, carbon dioxide is low-cost, easy to obtain, inert towards UV, non-poisonous and a good solvent for non-polar molecules. Other than carbon dioxide, ethane, n-butane, N2O, dichlorodifluoromethane, diethyl ether, ammonia, tetrahydrofuran can be used. Table \(\PageIndex{2}\) shows select solvents and their Tc and Pc values.

| Solvent | Critical Temperature (°C) | Critical Pressure (bar) |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon dioxide (CO2) | 31.1 | 72 |

| Nitrous oxide (N2O) | 36.5 | 70.6 |

| Ammonia (NH3) | 132.5 | 109.8 |

| Ethane (C2H6) | 32.3 | 47.6 |

| n-Butane (C4H10) | 152 | 70.6 |

| Diethyl ether (Et2O) | 193.6 | 63.8 |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF, C4H8O) | 267 | 50.5 |

| Dichlorodifluoromethane (CCl2F2) | 111.7 | 109.8 |

Detectors

One of the biggest advantage of SFC over HPLC is the range of detectors. Flame ionization detector (FID), which is normally present in GC setup, can also be applied to SFC. Such a detector can contribute to the quality of analyses of SFC since FID is a highly sensitive detector. SFC can also be coupled with a mass spectrometer, an UV-visible spectrometer, or an IR spectrometer more easily than can be done with an HPLC. Some other detectors which are used with HPLC can be attached to SFC such as fluorescence emission spectrometer or thermionic detectors.

Advantages of working with SFC

The physical properties of supercritical fluids between liquids and gases enables the SFC technique to combine with the best aspects of HPLC and GC, as lower viscosity of supercritical fluids makes SFC a faster method than HPLC. Lower viscosity leads to high flow speed for the mobile phase.

Thanks to the critical pressure of supercritical fluids, some fragile materials that are sensitive to high temperature can be analyzed through SFC. These materials can be compounds which decompose at high temperatures or materials which have low vapor pressure/volatility such as polymers and large biological molecules. High pressure conditions provide a chance to work with lower temperature than normally needed. Hence, the temperature-sensitive components can be analyzed via SFC. In addition, the diffusion of the components flowing through a supercritical fluid is higher than observed in HPLC due to the higher diffusivity of supercritical fluids over traditional liquids mobile phases. This results in better distribution into the mobile phase and better separation.

Applications of SFC

The applications of SFC range from food to environmental to pharmaceutical industries. In this manner, pesticides, herbicides, polymers, explosives and fossil fuels are all classes of compounds that can be analyzed. SFC can be used to analyze a wide variety of drug compounds such as antibiotics, prostaglandins, steroids, taxol, vitamins, barbiturates, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, etc. Chiral separations can be performed for many pharmaceutical compounds. SFC is dominantly used for non-polar compounds because of the low efficiency of carbon dioxide, which is the most common supercritical fluid mobile phase, for dissolving polar solutes. SFC is used in the petroleum industry for the determination of total aromatic content analysis as well as other hydrocarbon separations.

Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE)

The unique physical properties of supercritical fluids, having values for density, diffusivity and viscosity values between liquids and gases, enables supercritical fluid extraction to be used for the extraction processes which cannot be done by liquids due to their high density and low diffusivity and by gases due to their inadequate density in order to extract and carry the components out.

Complicated mixtures containing many components should be subject to an extraction process before they are separated via chromatography. An ideal extraction procedure should be fast, simple, and inexpensive. In addition, sample loss or decomposition should not be experienced at the end of the extraction. Following extraction, there should be a quantitative collection of each component. Ideally, the amount of unwanted materials coming from the extraction should be kept to a minimum and be easily disposable; the waste should not be harmful for environment. Unfortunately, traditional extraction methods often do not meet these requirements. In this regard, SFE has several advantages in comparison with traditional techniques.

The extraction speed is dependent on the viscosity and diffusivity of the mobile phase. With a low viscosity and high diffusivity, the component which is to be extracted can pass through the mobile phase easily. The higher diffusivity and lower viscosity of supercritical fluids, as compared to regular extraction liquids, help the components to be extracted faster than other techniques. Thus, an extraction process can take just 10-60 minutes with SFE, while it would take hours or even days with classical methods.

The dissolving efficiency of a supercritical fluid can be altered by temperature and pressure. In contrast, liquids are not affected by temperature and pressure changes as much. Therefore, SFE has the potential to be optimized to provide a better dissolving capacity.

In classical methods, heating is required to get rid of the extraction liquid. However, this step causes the temperature-sensitive materials to decompose. For SFE, when the critical pressure is removed, a supercritical fluid transforms to gas phase. Because supercritical fluid solvents are chemically inert, harmless and inexpensive; they can be released to atmosphere without leaving any waste. Through this, extracted components can be obtained much more easily and sample loss is minimized.

Instrumentation of SFE

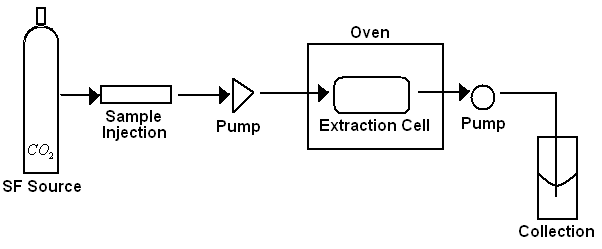

The necessary apparatus for a SFE setup is simple. Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) depicts the basic elements of a SFE instrument, which is composed of a reservoir of supercritical fluid, a pressure tuning injection unit, two pumps (to take the components in the mobile phase in and to send them out of the extraction cell), and a collection chamber.

There are two principle modes to run the instrument:

- Static extraction.

- Dynamic extraction.

In dynamic extraction, the second pump sending the materials out to the collection chamber is always open during the extraction process. Thus, the mobile phase reaches the extraction cell and extracts components in order to take them out consistently.

In the static extraction experiment, there are two distinct steps in the process:

- The mobile phase fills the extraction cell and interacts with the sample.

- The second pump is opened and the extracted substances are taken out at once.

In order to choose the mobile phase for SFE, parameters taken into consideration include the polarity and solubility of the samples in the mobile phase. Carbon dioxide is the most common mobile phase for SFE. It has a capability to dissolve non-polar materials like alkanes. For semi-polar compounds (such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, aldehydes, esters, alcohols, etc.) carbon dioxide can be used as a single component mobile phase. However, for compounds which have polar characteristic, supercritical carbon dioxide must be modified by addition of polar solvents like methanol (CH3OH). These extra solvents can be introduced into the system through a separate injection pump.

Extraction Modes

There are two modes in terms of collecting and detecting the components:

- Off-line extraction.

- On-line extraction.

Off-line extraction is done by taking the mobile phase out with the extracted components and directing them towards the collection chamber. At this point, supercritical fluid phase is evaporated and released to atmosphere and the components are captured in a solution or a convenient adsorption surface. Then the extracted fragments are processed and prepared for a separation method. This extra manipulation step between extractor and chromatography instrument can cause errors. The on-line method is more sensitive because it directly transfers all extracted materials to a separation unit, mostly a chromatography instrument, without taking them out of the mobile phase. In this extraction/detection type, there is no extra sample preparation after extraction for separation process. This minimizes the errors coming from manipulation steps. Additionally, sample loss does not occur and sensitivity increases.

Applications of SFE

SFE can be applied to a broad range of materials such as polymers, oils and lipids, carbonhydrates, pesticides, organic pollutants, volatile toxins, polyaromatic hydrocarbons, biomolecules, foods, flavors, pharmaceutical metabolites, explosives, and organometallics, etc. Common industrial applications include the pharmaceutical and biochemical industry, the polymer industry, industrial synthesis and extraction, natural product chemistry, and the food industry.

Examples of materials analyzed in environmental applications: oils and fats, pesticides, alkanes, organic pollutants, volatile toxins, herbicides, nicotin, phenanthrene, fatty acids, aromatic surfactants in samples from clay to petroleum waste, from soil to river sediments. In food analyses: caffeine, peroxides, oils, acids, cholesterol, etc. are extracted from samples such as coffee, olive oil, lemon, cereals, wheat, potatoes and dog feed. Through industrial applications, the extracted materials vary from additives to different oligomers, and from petroleum fractions to stabilizers. Samples analyzed are plastics, PVC, paper, wood etc. Drug metabolites, enzymes, steroids are extracted from plasma, urine, serum or animal tissues in biochemical applications.

Summary

Supercritical fluid chromatography and supercritical fluid extraction are techniques that take advantage of the unique properties of supercritical fluids. As such, they provide advantages over other related methods in both chromatography and extraction. Sometimes they are used as alternative analytical techniques, while other times they are used as complementary partners for binary systems. Both SFC and SFE demonstrate their versatility through the wide array of applications in many distinct domains in an advantageous way.