12.1: Crystal Lattices and Unit Cells

- Page ID

- 43268

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The Unit Cell

This section deals with the geometry of crystaline systems. These could describe how metal atoms pack when they form metallic solids, or how ions pack when they form ionic crystals. We will look at the ionic structures in the next section, and here focus on the generic unit cell and it's application to metallic structures.

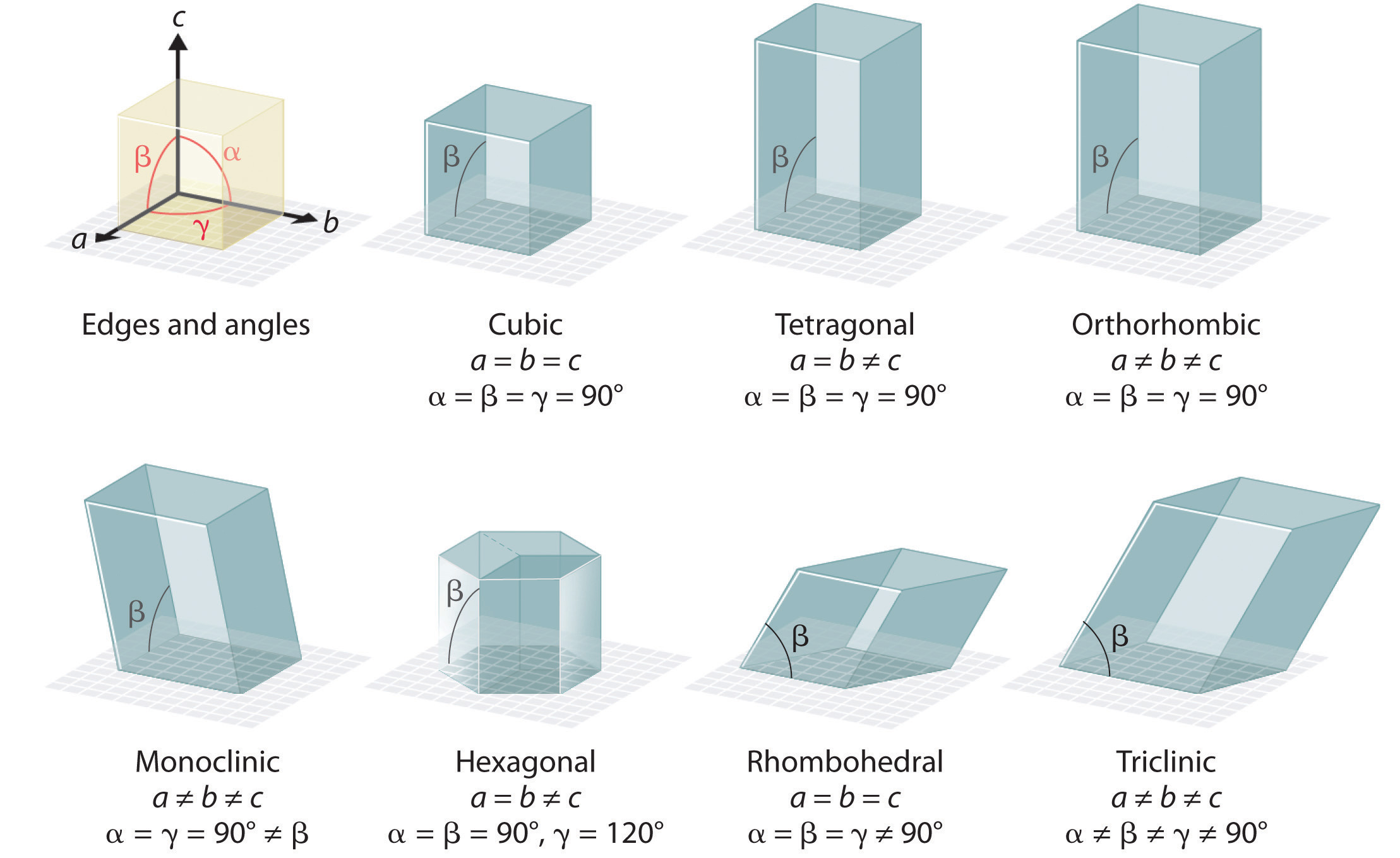

There are 7 types of unit cells (figure 12.1.a), defined by edge lengths (a,b,c) respectively along the x,y,z axis and angles \(\large\alpha\), \(\large\beta\), and \(\large\gamma\). In this class we will only focus on the cubic unit cell, and there are three types of cubic cells that you need to be familiar with, and these are represented in figure 12.1.b.

- \(\large\alpha\) = angle in the yz plane

- \(\large\beta\) = angle in the xz plane

- \(\large\gamma\) = angle in the xy plane

Cubic Unit Cell

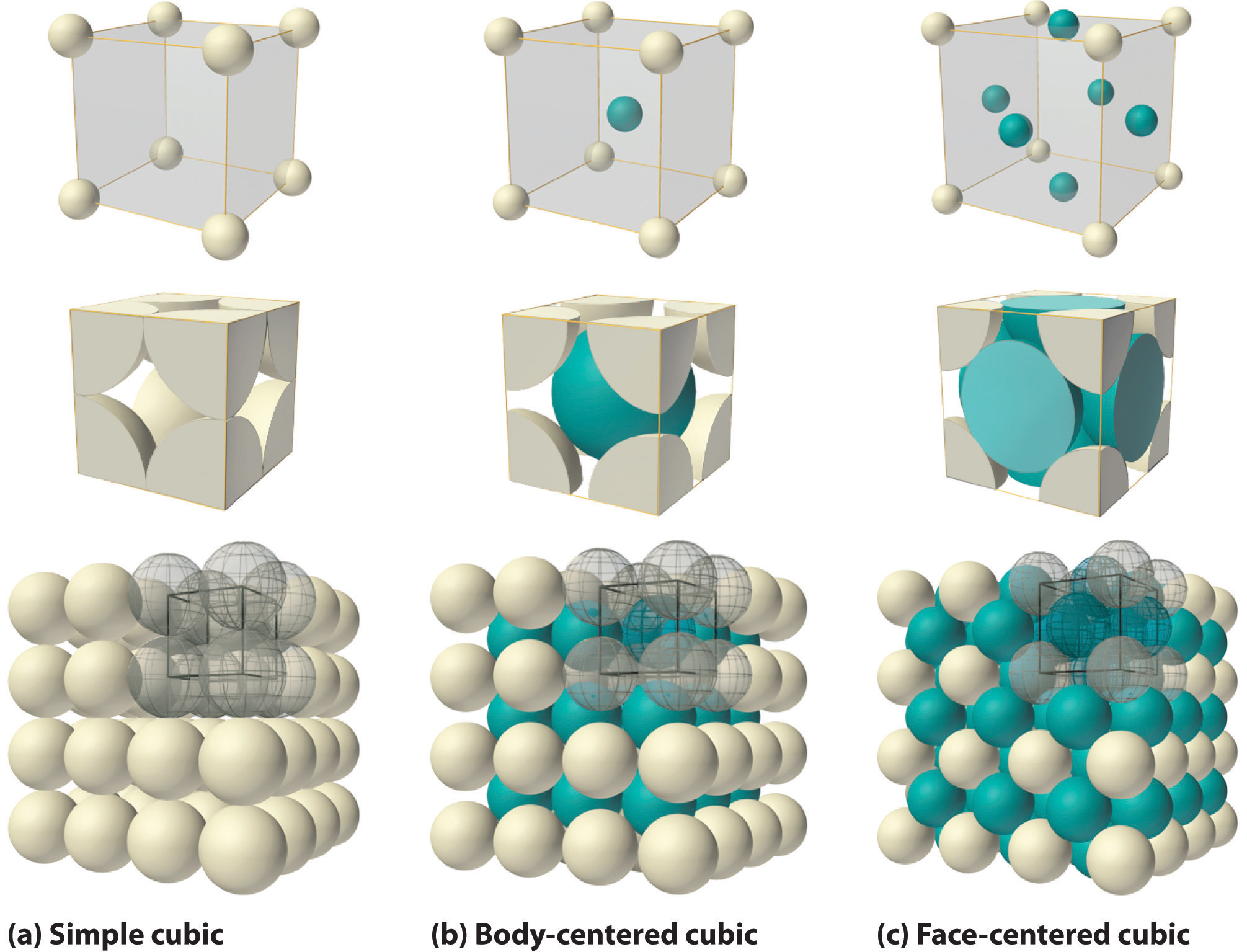

The cubic unit cell is the smallest repeating unit when all angles are 90o and all lengths are equal (figure 12.1.b) with each axis being defined by a Cartesian coordinate (x,y,z). Each cubic cell has 8 atoms in each corner of the cube, and that atom is shared with 8 neighboring cells. In the Body Centered Cubic Cell (BCC) there is an additional atom in the center of the cube, and in the face centered cubic cell, an atom is shared between two unit cells along the face. Please watch the YouTube video as this can help a lot.

Video\(\PageIndex{1}\): "Lattice Structure Part 1", created by Mark McClure, narrated by Sally Vallabha of UN-Pembroke, https://youtu.be/Rm-i1c7zr6Q

Simple (Primative) Cubic Unit Cell

- 1 particle per unit cell

- coordination number = 6

- 52% of space occupied by particles

- Simple Cubic Stacking

- along Cartesian coordinates

- very inefficient and rarely seen in nature (radioactive \(\alpha\) Polonium is the only known example at STP, Wikipedia)

Body centered cubic unit cell

- 2 particles per unit cell

- coordination number = 8

- 68% of space occupied by particles

- Hexagonal Close Packing (HCP)

- second layer sits in grove of first with third in grove of second and in line with first (ABA structure)

- Common with metals, including all alkali, Cr, V, Ba and Fe

Face Centered Cubic

- 4 particles per unit cell

- coordination number = 12

- 74% of space occupied by particles

- Cubic Closest Packing Structure

- explained in video 12.1.a at 5' 26".

- along Cartesian coordinates

- very inefficient and rarely seen in nature

Determining Atomic Radius from Density, Molar Mass and Crystal Structure

The strategy is to use the following to calculate the volume of the unit cell, and then the length of each side. Once this is done, you can use the packing and the geometry of the structure to calculate the radii. The information you need is:

- density

- Molar Mass

- Avogadro's number

- Number atoms per unit cell (1 for simple, 2 for body centered and 4 for face centered)

- Pythagorean theorem (a2 + b2 = c2)

- Volume of a cube (V=l3)

You may also want to review SI prefixes (section 1B.1.3.3 of General Chemistry 1) and not that 1 Å is 10-10m

So these all have a similar strategy

- Calculate Volume of Unit Cell (number of atoms in unit cell depends on type of cell)

- Calculate length of the sides of the unit cell (same for all)

- Use packing to figure radii (different for each type)

A. Simple Cubic Cell

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

A. Given the density of Polonium = 9.32g/ml, calculate radii of a Polonium atom if it forms a Simple Cubic Cell.

Problem: Polonium is the only element that is simple cubic (has 1 atom/unit cell). Note the length of unit cell is 2 radii, and thus if we can calculate the length of the unit cell, we can calculate the radius. When we say there is one atom per unit cell, we are not saying the volume of the atom is the volume of the unit cell. It is 52% the volume (see above).

Video\(\PageIndex{2}\): Solution to the radii of Po from its density.

- Answer

-

1. Find the volume of the unit cell

\[\frac{1 atom Po}{unit cell}(\frac{1mol Po}{6.02x10^{23}atoms})(\frac{208.9gPo}{mol})(\frac{1ml}{9.32g})=3.72x10^{-23}\frac{ml}{unit\: cell} \nonumber\]

2. Find the length of the unit cell

\[l=\sqrt[3]V]=\sqrt[3]{3.72x10^{-23}cm^{3}}=3.34x10^{-8}cm=334pm \nonumber\]

3. Find radii

Since each side is 2r, r is 1/2 half the length, or 167pm

-

.

B. Body Centered Cubic

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Problem: Molybdenum forms body centered cubic cells, if the density of Mo is 10.28 g/ml, what would its radius be?.

This is the toughest, as the diagonal through the cell from vertices X to Y with length "c" equals 4 radii. It makes a right triangle with side a and b, the diagonal of a face, we note that a2+a2=b2 and a2+b2=c2

- Answer

-

1. Find Volume of unit cell:

\[\frac{2 atom Mo}{unit cell}(\frac{1mol Mo}{6.02x10^{23}atoms})(\frac{95.95g\: Mo}{mol})(\frac{1ml\: Mo}{10.26g})=3.11x10^{-23}\frac{ml}{unit\: cell}\]

2. Find length of unit cell

\[[a=\sqrt[3]V]=\sqrt[3]{3.11x10^{-23}cm^{3}}=3.15x10^{-8}cm=314pm\]

3. Find radii

a. Find diagonal of face "b"

\[b=\sqrt[2]{2a^{2}}=\sqrt[2]{2(314)^{2}}=444pm\]b. Find diagonal through cube "c"

\[c=\sqrt[2]{a^{2}+b^{2}}=\sqrt[2]{314^{2}+444^{2}}=544pm\]c. "c" = 4r, so r=136pm

Note, in the video I used Å (Angstroms) while in the answer I used picometers. You should be able to convert between these, and review the "advanced technique" of section 1B.3.5.1 if needed, but we now that 1M = 1010 Å =1012pm, so the conversion factor from picometers to Angstroms is

\[\frac{10^{12}pm}{10^{10} Å } \; or \; \frac{10^2pm}{ Å }\]

C. Face Centered Cubic

Exercise \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Problem: Calcium forms a face centered cubic cell with a density of 1.54 g/ml, what would its radius be?

- Answer

-

1. Find Volume of unit cell:

\[\frac{4 atom Ca}{unit cell}(\frac{1mol CA}{6.02x10^{23}atoms})(\frac{40.08g\: Ca}{mol})(\frac{1ml\: Mo}{1.54g})=1.73x10^{-22}\frac{ml}{unit\: cell}\]

2. Find length of unit cell

\[a=\sqrt[3]V]=\sqrt[3]{1.72x10^{-22}cm^{3}}=5.57x10^{-8}cm=557pm\]

3. Find radii

a. Find diagonal of face "c"

\[c=\sqrt[2]{2a^{2}}=\sqrt[2]{2(557)^{2}}=787pm\]b. since the diagonal of the surface is 4r, r=197pm

Crystal Defects

Defects in a crystal can give it unique properties. Defects occur when another entity becomes part of the crystal, and there are many types of defects, two that are worth noting are substitutional and interstitial. A dopant is a compound that is added to a crystal and can alter its properties.

Substitutional Defects

These occur when a different substance substitutes for one of the components of the crystal. For example Ruby is Al2O3 with a few Cr+3 replacing Al+3 ions . Alloys involve one metal substituting for another. Bronze is a substitutional alloy of copper with about 12%, and Brass is an alloy of copper with zin, The properties of the alloy can be varied by changing the % composition.

Interstitial Defects

These occur when a substance which is not part of the crystal fits into the interstitial regions, and does not displace a component of the crystal. Carbide steel is a form of interstitial defect where carbon enters the holes of the iron structure, and this affects its properties like hardness and ductility.

In Class Activities

ADAPT \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Test Yourself

Query \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Query \(\PageIndex{2}\)

-

Contributors and Attributions

- Bob Belford

- some images from anonymous

- some images from anonymous were modified

- some images from Chris P Schaller