4.4: Shifting Equilibria - Le Chatelier’s Principle

- Page ID

- 364663

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Predict whether reactants or products are favored in a given reaction based on the equilibrium constant

- Describe the ways in which an equilibrium system can be stressed

- Predict the response of a stressed equilibrium using Le Chatelier’s principle

Reversible reactions proceed in both directions (reactants go to products and products go to reactants). We can tell a reaction is at equilibrium if the reaction quotient (\(Q\)) is equal to the equilibrium constant (K). In this section, you will learn to predict whether reactants or products are favored at equilbrium, and how to predict the direction a reaction will proceed when its equilibrium is disturbed.

Relating K to the Reaction Mixture Composition

Many reactions have equilibrium constants between 1000 and 0.001 (\(10^3 \ge K \ge 10^{-3}\)), neither very large nor very small. At equilibrium, these systems tend to contain significant amounts of both products and reactants, indicating that there is not a strong tendency to form either products from reactants or reactants from products. An example of this type of system is the reaction of gaseous hydrogen and deuterium, a component of high-stability fiber-optic light sources used in ocean studies, to form \(\ce{HD}\):

\[\ce{H2(g) + D2(g) <=> 2HD(g)} \nonumber\]

The equilibrium constant expression for this reaction is

\[K= \dfrac{[HD]^2}{[H_2][D_2]} \nonumber\]

with \(K\) varying between 1.9 and 4 over a wide temperature range (100–1000 K). Thus an equilibrium mixture of \(H_2\), \(D_2\), and \(HD\) contains significant concentrations of both product and reactants.

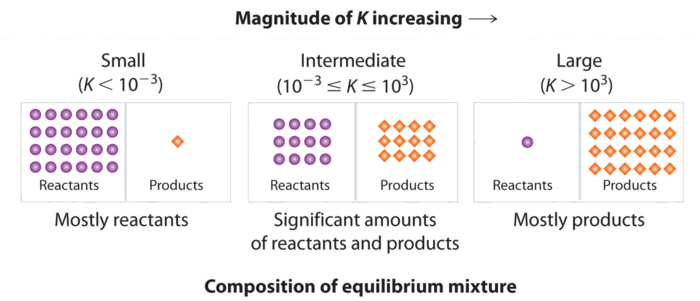

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) summarizes the relationship between the magnitude of K and the relative concentrations of reactants and products at equilibrium for a general reaction, written as reactants \(\rightleftharpoons\) products. Because there is a direct relationship between the kinetics of a reaction and the equilibrium concentrations of products and reactants (Equations \(\ref{Eq8}\) and \(\ref{Eq7}\)), when \(k_f \gg k_r\), \(K\) is a large number, and the concentration of products at equilibrium predominate. This corresponds to an essentially irreversible reaction. Conversely, when \(k_f \ll k_r\), \(K\) is a very small number, and the reaction produces almost no products as written. Systems for which \(k_f ≈ k_r\) have significant concentrations of both reactants and products at equilibrium.

A large value of the equilibrium constant \(K\) means that products predominate at equilibrium; a small value means that reactants predominate at equilibrium.

Predict which systems at equilibrium will (a) contain essentially only products, (b) contain essentially only reactants, and (c) contain appreciable amounts of both products and reactants.

- \(H_{2(g)}+I_{2(g)} \rightleftharpoons 2HI_{(g)}\;\;\; K_{(700K)}=54\)

- \(2CO_{2(g)} \rightleftharpoons 2CO_{(g)}+O_{2(g)}\;\;\; K_{(1200K)}=3.1 \times 10^{-18}\)

- \(PCl_{5(g)} \rightleftharpoons PCl_{3(g)}+Cl_{2(g)}\;\;\; K_{(613K)}=97\)

- \(2O_{3(g)} \rightleftharpoons 3O_{2(g)} \;\;\; K_{(298 K)}=5.9 \times 10^{55}\)

Strategy:

Use the value of the equilibrium constant to determine whether the equilibrium mixture will contain essentially only products, essentially only reactants, or significant amounts of both.

Solution:

- Only system 4 has \(K \gg 10^3\), so at equilibrium it will consist of essentially only products.

- System 2 has \(K \ll 10^{-3}\), so the reactants have little tendency to form products under the conditions specified; thus, at equilibrium the system will contain essentially only reactants.

- Both systems 1 and 3 have equilibrium constants in the range \(10^3 \ge K \ge 10^{-3}\), indicating that the equilibrium mixtures will contain appreciable amounts of both products and reactants.

Hydrogen and nitrogen react to form ammonia according to the following balanced chemical equation:

\[\ce{3H2(g) + N2(g) <=> 2NH3(g)} \nonumber\]

Values of the equilibrium constant at various temperatures were reported as

- \(K_{25°C} = 3.3 \times 10^8\),

- \(K_{177°C} = 2.6 \times 10^3\), and

- \(K_{327°C} = 4.1\).

- At which temperature would you expect to find the highest proportion of \(H_2\) and \(N_2\) in the equilibrium mixture?

- Assuming that the reaction rates are fast enough so that equilibrium is reached quickly, at what temperature would you design a commercial reactor to operate to maximize the yield of ammonia?

- Answer a

-

327°C, where \(K\) is smallest

- Answer b

-

25°C

Video which Discusses What Does K Tell us About a Reaction?: https://youtu.be/39-456o3O_4

Predicting the Direction of a Reversible Reaction

We next address what happens when a system at equilibrium is disturbed so that \(Q\) is no longer equal to \(K\). If a system at equilibrium is subjected to a perturbance or stress (such as a change in concentration) the position of equilibrium changes. Since this stress affects the concentrations of the reactants and the products, the value of \(Q\) will no longer equal the value of \(K\). To re-establish equilibrium, the system will either shift toward the products (if \(Q < K\)) or the reactants (if \(Q > K\)) until \(Q\) returns to the same value as \(K\).

This process is described by Le Chatelier's principle: When a chemical system at equilibrium is disturbed, it returns to equilibrium by counteracting the disturbance. As described in the previous paragraph, the disturbance causes a change in \(Q\); the reaction will shift to re-establish \(Q = K\).

Le Chatelier's principle can be used to predict changes in equilibrium concentrations when a system that is at equilibrium is subjected to a stress. However, if we have a mixture of reactants and products that have not yet reached equilibrium, the changes necessary to reach equilibrium may not be so obvious. In such a case, we can compare the values of Q and K for the system to predict the changes.

A chemical system at equilibrium can be temporarily shifted out of equilibrium by adding or removing one or more of the reactants or products. The concentrations of both reactants and products then undergo additional changes to return the system to equilibrium.

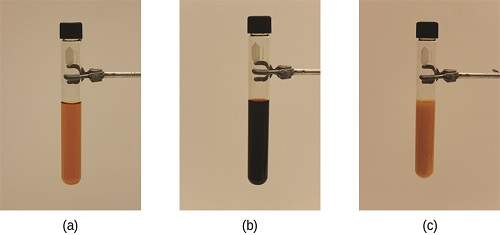

The stress on the system in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) is the reduction of the equilibrium concentration of SCN− (lowering the concentration of one of the reactants would cause Q to be larger than K). As a consequence, Le Chatelier's principle leads us to predict that the concentration of Fe(SCN)2+ should decrease, increasing the concentration of SCN− part way back to its original concentration, and increasing the concentration of Fe3+ above its initial equilibrium concentration.

The effect of a change in concentration on a system at equilibrium is illustrated further by the equilibrium of this chemical reaction:

\[\ce{H}_{2(g)}+\ce{I}_{2(g)} \rightleftharpoons \ce{2HI}_{(g)} \label{13.4.1a}\]

\[K_c=\mathrm{50.0 \; at\; 400°C} \label{13.4.1b}\]

The numeric values for this example have been determined experimentally. A mixture of gases at 400 °C with \(\mathrm{[H_2] = [I_2]} = 0.221\; M\) and \(\ce{[HI]} = 1.563 \;M\) is at equilibrium; for this mixture, \(Q_c = K_c = 50.0\). If \(\ce{H_2}\) is introduced into the system so quickly that its concentration doubles before it begins to react (new \(\ce{[H_2]} = 0.442\; M\)), the reaction will shift so that a new equilibrium is reached, at which

- \(\ce{[H_2]} = 0.374\; M\),

- \(\ce{[I_2]} = 0.153\; M\), and

- \(\ce{[HI]} = 1.692\; M\).

This gives:

\[Q_c=\mathrm{\dfrac{[HI]^2}{[H_2][I_2]}}=\dfrac{(1.692)^2}{(0.374)(0.153)}=50.0=K_c \label{13.4.2}\]

We have stressed this system by introducing additional \(\ce{H_2}\). The stress is relieved when the reaction shifts to the right, using up some (but not all) of the excess \(\ce{H_2}\), reducing the amount of uncombined \(\ce{I_2}\), and forming additional \(\ce{HI}\).

Effect of Change in Pressure on Equilibrium

Sometimes we can change the position of equilibrium by changing the pressure of a system. However, changes in pressure have a measurable effect only in systems in which gases are involved, and then only when the chemical reaction produces a change in the total number of gas molecules in the system. An easy way to recognize such a system is to look for different numbers of moles of gas on the reactant and product sides of the equilibrium. While evaluating pressure (as well as related factors like volume), it is important to remember that equilibrium constants are defined with regard to concentration (for \(K_c\)) or partial pressure (for \(K_P\)). Some changes to total pressure, like adding an inert gas that is not part of the equilibrium, will change the total pressure but not the partial pressures of the gases in the equilibrium constant expression. Thus, addition of a gas not involved in the equilibrium will not perturb the equilibrium.

As we increase the pressure of a gaseous system at equilibrium, either by decreasing the volume of the system or by adding more of one of the components of the equilibrium mixture, we introduce a stress by increasing the partial pressures of one or more of the components. In accordance with Le Chatelier's principle, a shift in the equilibrium that reduces the total number of molecules per unit of volume will be favored because this relieves the stress. The reverse reaction would be favored by a decrease in pressure.

Consider what happens when we increase the pressure on a system in which \(\ce{NO}\), \(\ce{O_2}\), and \(\ce{NO_2}\) are at equilibrium:

\[\ce{2NO (g) + O2(g) \rightleftharpoons 2NO2(g)} \label{13.4.3}\]

The formation of additional amounts of \(\ce{NO2}\) decreases the total number of molecules in the system because each time two molecules of \(\ce{NO_2}\) form, a total of three molecules of \(\ce{NO}\) and \(\ce{O_2}\) are consumed. This reduces the total pressure exerted by the system and reduces, but does not completely relieve, the stress of the increased pressure. On the other hand, a decrease in the pressure on the system favors decomposition of \(\ce{NO_2}\) into \(\ce{NO}\) and \(\ce{O_2}\), which tends to restore the pressure.

Now consider this reaction:

\[\ce{N2 (g) + O2 (g) \rightleftharpoons 2NO (g)} \label{13.4.4}\]

Because there is no change in the total number of molecules in the system during reaction, a change in pressure does not favor either formation or decomposition of gaseous nitrogen monoxide.

Effect of Change in Temperature on Equilibrium

Changing concentration or pressure perturbs an equilibrium because the reaction quotient is shifted away from the equilibrium value. Changing the temperature of a system at equilibrium has a different effect: A change in temperature actually changes the value of the equilibrium constant. However, we can qualitatively predict the effect of the temperature change by treating it as a stress on the system and applying Le Chatelier's principle.

When hydrogen reacts with gaseous iodine, heat is evolved.

\[\ce{H2(g) + I2(g) \rightleftharpoons 2HI(g) } \;\;\ ΔH=\mathrm{−9.4\;kJ\;(exothermic)} \label{13.4.5}\]

Because this reaction is exothermic, we can write it with heat as a product.

\[\ce{H2(g) + I2(g) \rightleftharpoons 2HI(g)} + \text{heat} \label{13.4.6}\]

Increasing the temperature of the reaction increases the internal energy of the system. Thus, increasing the temperature has the effect of increasing the amount of one of the products of this reaction. The reaction shifts to the left to relieve the stress, and there is an increase in the concentration of \(\ce{H2}\) and \(\ce{I2}\) and a reduction in the concentration of \(\ce{HI}\). Lowering the temperature of this system reduces the amount of energy present, favors the production of heat, and favors the formation of hydrogen iodide.

When we change the temperature of a system at equilibrium, the equilibrium constant for the reaction changes. Lowering the temperature in the \(\ce{HI}\) system increases the equilibrium constant: At the new equilibrium the concentration of \(\ce{HI}\) has increased and the concentrations of \(\ce{H2}\) and \(\ce{I2}\) decreased. Raising the temperature decreases the value of the equilibrium constant, from 67.5 at 357 °C to 50.0 at 400 °C.

Temperature affects the equilibrium between \(\ce{NO_2}\) and \(\ce{N_2O_4}\) in this reaction

\[\ce{N2O4(g) \rightleftharpoons 2NO2(g)}\;\;\; ΔH=\mathrm{57.20\; kJ} \label{13.4.7}\]

The positive ΔH value tells us that the reaction is endothermic and could be written

\[\text{heat}+\ce{N2O4(g) \rightleftharpoons 2NO2(g)} \label{13.4.8}\]

At higher temperatures, the gas mixture has a deep brown color, indicative of a significant amount of brown \(\ce{NO_2}\) molecules. If, however, we put a stress on the system by cooling the mixture (withdrawing energy), the equilibrium shifts to the left to supply some of the energy lost by cooling. The concentration of colorless \(\ce{N_2O_4}\) increases, and the concentration of brown \(\ce{NO_2}\) decreases, causing the brown color to fade.

Catalysts Do Not Affect Equilibrium

As we learned during our study of kinetics, a catalyst can speed up the rate of a reaction. Though this increase in reaction rate may cause a system to reach equilibrium more quickly (by speeding up the forward and reverse reactions), a catalyst has no effect on the value of an equilibrium constant nor on equilibrium concentrations.

The interplay of changes in concentration or pressure, temperature, and the lack of an influence of a catalyst on a chemical equilibrium is illustrated in the industrial synthesis of ammonia from nitrogen and hydrogen according to the equation

\[\ce{N2(g) + 3H2(g) \rightleftharpoons 2NH3(g)} \label{13.4.9}\]

A large quantity of ammonia is manufactured by this reaction. Each year, ammonia is among the top 10 chemicals, by mass, manufactured in the world. About 2 billion pounds are manufactured in the United States each year. Ammonia plays a vital role in our global economy. It is used in the production of fertilizers and is, itself, an important fertilizer for the growth of corn, cotton, and other crops. Large quantities of ammonia are converted to nitric acid, which plays an important role in the production of fertilizers, explosives, plastics, dyes, and fibers, and is also used in the steel industry.

Haber was born in Breslau, Prussia (presently Wroclaw, Poland) in December 1868. He went on to study chemistry and, while at the University of Karlsruhe, he developed what would later be known as the Haber process: the catalytic formation of ammonia from hydrogen and atmospheric nitrogen under high temperatures and pressures.

For this work, Haber was awarded the 1918 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for synthesis of ammonia from its elements. The Haber process was a boon to agriculture, as it allowed the production of fertilizers to no longer be dependent on mined feed stocks such as sodium nitrate.

\[\ce{N2(g) + 3H2(g) \rightleftharpoons 2NH3(g)}\]

Currently, the annual production of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers exceeds 100 million tons and synthetic fertilizer production has increased the number of humans that arable land can support from 1.9 persons per hectare in 1908 to 4.3 in 2008. The availability of nitrogen is a strong limiting factor to the growth of plants. Despite accounting for 78% of air, diatomic nitrogen (\(\ce{N_2}\)) is nutritionally unavailable due the tremendous stability of the nitrogen-nitrogen triple bond. For plants to use atmospheric nitrogen, the nitrogen must be converted to a more bioavailable form (this conversion is called nitrogen fixation).

In addition to his work in ammonia production, Haber is also remembered by history as one of the fathers of chemical warfare. During World War I, he played a major role in the development of poisonous gases used for trench warfare. Regarding his role in these developments, Haber said, “During peace time a scientist belongs to the World, but during war time he belongs to his country.”1 Haber defended the use of gas warfare against accusations that it was inhumane, saying that death was death, by whatever means it was inflicted. He stands as an example of the ethical dilemmas that face scientists in times of war and the double-edged nature of the sword of science.

Like Haber, the products made from ammonia can be multifaceted. In addition to their value for agriculture, nitrogen compounds can also be used to achieve destructive ends. Ammonium nitrate has also been used in explosives, including improvised explosive devices. Ammonium nitrate was one of the components of the bomb used in the attack on the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in downtown Oklahoma City on April 19, 1995.

It has long been known that nitrogen and hydrogen react to form ammonia. However, it became possible to manufacture ammonia in useful quantities by the reaction of nitrogen and hydrogen only in the early 20th century after the factors that influence its equilibrium were understood.

To be practical, an industrial process must give a large yield of product relatively quickly. One way to increase the yield of ammonia is to increase the pressure on the system in which N2, H2, and NH3 are at equilibrium or are coming to equilibrium.

\[\ce{N2(g) + 3H2(g) \rightleftharpoons 2NH3(g)} \label{13.4.10}\]

The formation of additional amounts of ammonia reduces the total pressure exerted by the system and somewhat reduces the stress of the increased pressure.

Although increasing the pressure of a mixture of N2, H2, and NH3 will increase the yield of ammonia, at low temperatures, the rate of formation of ammonia is slow. At room temperature, for example, the reaction is so slow that if we prepared a mixture of N2 and H2, no detectable amount of ammonia would form during our lifetime. The formation of ammonia from hydrogen and nitrogen is an exothermic process:

\[\ce{N2(g) + 3H2(g) \rightarrow 2NH3(g)} \;\;\; ΔH=\mathrm{−92.2\; kJ} \label{13.4.11}\]

Thus, increasing the temperature to increase the rate lowers the yield. If we lower the temperature to shift the equilibrium to favor the formation of more ammonia, equilibrium is reached more slowly because of the large decrease of reaction rate with decreasing temperature.

Part of the rate of formation lost by operating at lower temperatures can be recovered by using a catalyst. The net effect of the catalyst on the reaction is to cause equilibrium to be reached more rapidly. In the commercial production of ammonia, conditions of about 500 °C, 150–900 atm, and the presence of a catalyst are used to give the best compromise among rate, yield, and the cost of the equipment necessary to produce and contain high-pressure gases at high temperatures.

Summary

The magnitude of an equilibrium constant will allow you to predict whether the reactants or products will be in excess when the system is at equilibrium. Systems at equilibrium can be disturbed by changes to temperature, concentration, and, in some cases, volume and pressure; volume and pressure changes will disturb equilibrium if the number of moles of gas is different on the reactant and product sides of the reaction. The system's response to these disturbances is described by Le Chatelier's principle: The system will respond in a way that counteracts the disturbance. Not all changes to the system result in a disturbance of the equilibrium. Adding a catalyst affects the rates of the reactions but does not alter the equilibrium, and changing pressure or volume will not significantly disturb systems with no gases or with equal numbers of moles of gas on the reactant and product side.

| Disturbance | Observed Change as Equilibrium is Restored | Direction of Shift | Effect on K |

|---|---|---|---|

| reactant added | added reactant is partially consumed | toward products | none |

| product added | added product is partially consumed | toward reactants | none |

| decrease in volume/increase in gas pressure | pressure decreases | toward side with fewer moles of gas | none |

| increase in volume/decrease in gas pressure | pressure increases | toward side with more moles of gas | none |

| temperature increase | heat is absorbed | toward products for endothermic, toward reactants for exothermic | changes |

| temperature decrease | heat is given off | toward reactants for endothermic, toward products for exothermic | changes |

Footnotes

- Herrlich, P. “The Responsibility of the Scientist: What Can History Teach Us About How Scientists Should Handle Research That Has the Potential to Create Harm?” EMBO Reports 14 (2013): 759–764.

Glossary

- Le Chatelier's principle

- when a chemical system at equilibrium is disturbed, it returns to equilibrium by counteracting the disturbance

- position of equilibrium

- concentrations or partial pressures of components of a reaction at equilibrium (commonly used to describe conditions before a disturbance)

- stress

- change to a reaction's conditions that may cause a shift in the equilibrium