24.4: Half-Life

- Page ID

- 53983

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Uranium isotopes produce plutonium-239 as a decay product. The plutonium can be used in nuclear weapons and is a power source for nuclear reactors, which generate electricity. This isotope has a half-life of 24,100 years, causing concern in regions where radioactive plutonium has accumulated and is stored. At some storage sites, the waste is slowly leaking into the groundwater and contaminating nearby rivers. The 24,100 year half-life means that it will be present in the earth for a very long time.

Half-Life

Radioactive materials lose some of their activity each time a decay event occurs. This loss of activity can be estimated by determining the half-life of an isotope. The half-life is defined as the period of time needed for one half of a given quantity of a substance to undergo a change. For a radioisotope, every time a decay event occurs, a count is detected on the Geiger counter, or other measuring device. A specific isotope might have a total count of \(30,000 \: \text{cpm}\). In one hour, the count could be \(15,000 \: \text{cpm}\) (half of the original count). So, the half-life of that isotope is one hour. Some isotopes have long half-lives—the half-life of \(\ce{U}\)-234 is 245,000 years. Other isotopes have shorter half-lives. \(\ce{I}\)-131, used in thyroid scans, has a half-life of 8.02 days.

Half-Life Calculations

Information on the half-life of an isotope can be used to calculate how much radioactivity of that isotope will be present after a certain period of time. There is a formula that allows calculation at any time after the initial count, but we are just going to look at loss of activity after different half-lives. The isotope \(\ce{I}\)-125 is used in certain laboratory procedures and has a half-life of 59.4 days. If the initial activity of a sample of \(\ce{I}\)-125 is \(32,000 \: \text{cpm}\), how much activity will be present in 178.2 days? Begin by determining how many half-lives are represented by 178.2 days:

\[\frac{178.2 \: \text{days}}{59.4 \: \text{days/half-life}} = 3 \: \text{half-lives}\nonumber \]

Then, simply count activity:

\[\begin{align*} \text{initial activity} \: \left( t_0 \right) &= 32,000 \: \text{cpm} \\ \text{after one half-life} \: &= 16,000 \: \text{cpm} \\ \text{after two half-lives} \: &= 8,000 \: \text{cpm} \\ \text{after three half-lives} &= 4,000 \: \text{cpm} \end{align*}\nonumber \]

Be sure to keep in mind that the initial count is at time zero \(\left( t_0 \right)\), and to subtract from that count at the first half-life. The second half-life has an activity of half the previous count (not the initial count).

For the more mathematically inclined, the following formula can be used to calculate the amount of radioactivity remaining after a given time:

\[N_t = N_0 \times \left( 0.5 \right)^\text{number of half-lives}\nonumber \]

where \(N_t =\) activity at time \(t\) and \(N_0 =\) initial activity at time \(t = 0\).

If we have an initial activity of \(42,000 \: \text{cpm}\), what will the activity be after four half-lives?

\[\begin{align*} N_t &= N_0 \left( 0.5 \right)^4 \\ &= \left( 42,000 \right) \left( 0.5 \right) \left( 0.5 \right) \left( 0.5 \right) \left( 0.5 \right) \\ &= 2625 \: \text{cpm} \end{align*}\nonumber \]

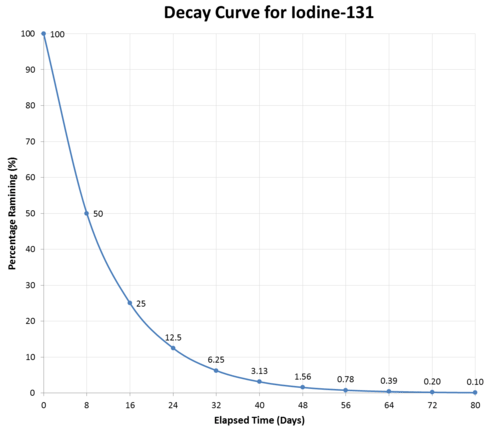

The graph above illustrates a typical decay curve for a radioactive material. The activity decreases by one-half during each succeeding half-life. Half-lives of different elements vary considerably, as shown in the table below:

| Isotope | Decay Mode | Half-Life |

|---|---|---|

| Cobalt-60 | beta | 5.3 years |

| Neptunium-237 | alpha | 2.1 million years |

| Polonium-214 | alpha | 0.00016 seconds |

| Radium-224 | alpha | 3.7 days |

| Tritium (\(\ce{H}\)-3) | beta | 12 years |

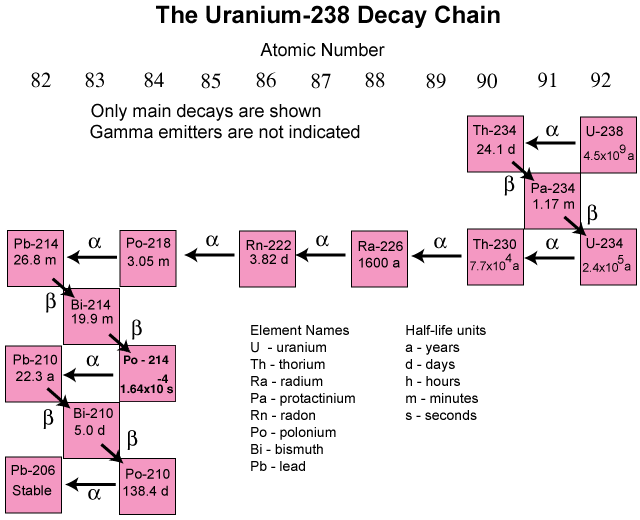

We have talked about the activity and decay of individual isotopes. In the real world, there is a decay chain that takes place until a stable end-product is produced. For \(\ce{U}\)-238, the chain is a long one, with a mix of isotopes having very different half-lives. The end of the chain resides in lead, a stable element that does not decay further.

Summary

- Radioactive materials lose some of their activity each time a decay event occurs.

- Radioactive loss of activity can be estimated by determining the half-life of an isotope.

- Half-life is defined as the period of time needed for one half of a given quantity of a substance to undergo a change.

- Half-lives of different elements vary considerably.