6.7: Acid-base reactions

- Page ID

- 371808

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Acid-base reactions are chemical reactions that involve the transfer of a proton (H+). Examples include the reactions of acids with metals, carbonates, and Arrhenius bases, described in the following.

Reactions of acids with metals

Metals tend to give out an electron and become cations. The majority of the metals, called reactive metals, give out electrons to protons in the acids and release H2 gas. For example, Fig. 6.7.1 shows magnesium reacting with hydrochloric acid by the following reaction:

\[\mathrm{Mg}(\mathrm{s})+2 \mathrm{HCl} \rightarrow \mathrm{MgCl}_{2}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{H}_{2}(\mathrm{~g}) \uparrow\nonumber\]

Alkali metals like Na give out one electron, alkaline earth metals like Mg give out two electrons, and aluminum gives out three electrons. A proton can accept one electron. Therefore, the number of acidic protons should be equal to the number of electrons given out to balance the electron transfer in these reactions.

Noble metals or jewelry metals like gold, silver, platinum, copper are exceptions –they do not react with acids.

write a balanced equation for the reaction of aluminum with HBr?

Solution

Step 1) write the equation with the correct formulas of reactants and products.

\[\mathrm{Al}(\mathrm{s})+\mathrm{HBr}(\mathrm{aq}) \rightarrow \mathrm{AlBr}_{3}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{H}_{2}(\mathrm{~g})\nonumber\]

Note that Al gives out three electrons to make Al3+; that is why three Br- are attached to it in the product to balance the charge.

Step 2) balance the electrons lost by the metal with the number of acidic protons.

\[\mathrm{Al}(\mathrm{s})+3 \mathrm{HBr}(\mathrm{aq}) \rightarrow \mathrm{AlBr}_{3}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{H}_{2}(\mathrm{~g})\nonumber\]

Step 3) Balance the rest of the elements by the hit and trial method. There are 3 hydrogen atoms on the left, balance them by adding 3/2 coefficient to the hydrogen on the right.

\[\mathrm{Al}(\mathrm{s})+3 \mathrm{HBr}(\mathrm{aq}) \rightarrow \mathrm{AlBr}_{3}(\mathrm{aq})+\frac{3}{2} \mathrm{H}_{2}(\mathrm{~g})\nonumber\]

Step 4. Although the equation is balanced, it is recommended to remove the fraction by multiplying the coefficients in the whole equation with the highest common factor to obtain the final balanced equation.

\[2 \mathrm{Al}(\mathrm{s})+6 \mathrm{HBr}(\mathrm{aq}) \rightarrow 2 \mathrm{AlBr}_{3}(\mathrm{aq})+3 \mathrm{H}_{2}(\mathrm{~g})\nonumber\]

Reactions of acids with carbonates and hydrogen carbonates

Carbonic acid (H2CO3) is a weak acid found in carbonated water. The H2CO3 is a product of carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O) by the following equilibrium reaction.

\[\ce{CO2(aq) + H2O(l) <=> H2CO3(aq)}\nonumber\]

Hydrogen carbonate (HCO3-) and carbonate (CO32-) are one and two hydrogen less, respectively than carbonic acid. The salts containing HCO3- and CO32- accept one and two protons, respectively, from acids to make H2CO3. The H2CO3 decomposes to carbon dioxide and water by the reverse reaction shown above. Fig. 6.7.2 shows the reaction of sodium hydrogen carbonate with hydrochloric acid.

\[\mathrm{NaHCO}_{3}(\mathrm{~s})+\mathrm{HCl}(\mathrm{aq}) \rightarrow \mathrm{NaCl}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{I})+\mathrm{CO}_{2}(\mathrm{~g}) \uparrow\nonumber\]

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): The reaction of sodium carbonate with HCl. Before and after HCl addition. Carbon dioxide bubbles out after HCl addition. Source: NCSSM, 05/18/20, https://youtu.be/TJYOxGHNTzg, CC BY 3.0

Similarly, calcium carbonate found in limestone reacts with acids. For example, sulfuric acid is one of the components in acid rain that reacts with calcium carbonate and damages sculptures made of stone.

\[\mathrm{CaCO}_{3}(\mathrm{~s})+\mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{SO}_{4}(\mathrm{aq}) \rightarrow \mathrm{CaSO}_{4}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{l})+\mathrm{CO}_{2}(\mathrm{~g}) \uparrow\nonumber\]

Reactions of acids with Arrhenius bases

Acids release proton (H+) and Arrhenius bases release hydroxide ions (OH-) in solution. When an acid mix with the Arrhenius base, H+ and OH- ions react with each other and produce water molecules.

\[\mathrm{H}^{+}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{OH}^{-}(\mathrm{aq}) \rightarrow \mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{l})\nonumber\]

This is the net ionic equation of a reaction of an acid with an Arrhenius base. The cation of the base and the anion of the acid do not react –they are spectator ions. The reaction equation for an acid-base reaction is written in various ways explained below.

Molecular equation

The molecular equation shows the formulas of the substances. For example, the molecular equation of the reaction of HCl with NaOH is the following.

\[\mathrm{HCl}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{NaOH}(a q) \rightarrow \mathrm{NaCl}(a q)+\mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{l})\nonumber\]

Complete ionic equation

The complete ionic equation shows the electrolytes dissociated into ions as they actually exist in the water phase, i.e., as aqueous ions. The complete ionic equation of the reaction of HCl with NaOH is the following.

\[\mathrm{H}^{+}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{Cl}^{-}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{Na}^{+}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{OH}^{-}(\mathrm{aq}) \rightarrow \mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{l})+\mathrm{Na}^{+}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{Cl}^{-}(\mathrm{aq})\nonumber\]

It is evident that Na+ and Cl- do not react –they are the spectator ions.

Net ionic equation

The spectator ions are present on both sides of the equation in equal numbers. The spectator ions can be canceled out, like the terms in an algebraic equation.

\[\mathrm{H}^{+}(\mathrm{aq})+\cancel{\mathrm{Cl}^{-}(\mathrm{aq})}+\cancel{\mathrm{Na}^{+}(\mathrm{aq})}+\mathrm{OH}^{-}(\mathrm{aq}) \rightarrow \mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{l})+\cancel{\mathrm{Na}^{+}(\mathrm{aq})}+\cancel{\mathrm{Cl}^{-}(\mathrm{aq})}\nonumber\]

The net ionic equation shows the substances that are not spectator ions after canceling out the spectator ions from the complete ionic equation. The net ionic equation of the reaction of HCl with NaOH is the following.

\[\mathrm{H}^{+}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{OH}^{-}(\mathrm{aq}) \rightarrow \mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{l})\nonumber\]

All of the reactions of the strong acids with strong Arrhenius bases have the same net ionic equation.

Writing a balanced chemical equation of the reaction of acids with Arrhenius bases

The following example shows the steps needed to write the balanced equation of the reaction of an acid with an Arrhenius base.

Write a balanced chemical equation of a reaction between HCl and Ca(OH)2?

Solution

Step 1) Write the formula of acid and base in the reactants and salt and water in the products. All the strong electrolytes dissolve in water, so use (aq) to represent their state.

\[\mathrm{HCl}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{Ca}(\mathrm{OH})_{2}(\mathrm{aq}) \rightarrow \text { Salt(aq) }+\mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{l})\nonumber\]

Step 2) Balance the H+ in the acid with the OH- in the base.

\[2 \mathrm{HCl}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{Ca}(\mathrm{OH})_{2}(\mathrm{aq}) \rightarrow \mathrm{Salt}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{l})\nonumber\]

Step 3) Balance the H2O with the H+ in the acid, or with the OH- in the base.

\[2 \mathrm{HCl}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{Ca}(\mathrm{OH})_{2}(\mathrm{aq}) \rightarrow \text { Salt }(\mathrm{aq})+2 \mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{I})\nonumber\]

Step 4) Write the salt by combing the cations from the base and the anions from the acid. Make sure the charges are balanced in the salt to make it a neutral substance.

\[2 \mathrm{HCl}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{Ca}(\mathrm{OH})_{2}(\mathrm{aq}) \rightarrow \mathrm{CaCl}_{2}(\mathrm{aq})+2 \mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{I})\]

Write a balanced chemical equation of a reaction between H2SO4 and Ba(OH)2?

Solution

Step 1) Write the formula of acid and base in the reactants and salt and water in the products. All the strong electrolytes dissolve in water, so use (aq) to represent their state.

\[\mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{SO}_{4}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{Ba}(\mathrm{OH})_{2}(\mathrm{aq}) \rightarrow \mathrm{Salt}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{l})\nonumber\]

Step 2) Balance the H+ in the acid with the OH- in the base. They are already balanced in the above equation.

Step 3) Balance the H2O with the H+ in the acid, or with the OH- in the base.

\[\mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{SO}_{4}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{Ba}(\mathrm{OH})_{2}(\mathrm{aq}) \rightarrow \mathrm{Salt}(\mathrm{aq})+2 \mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{l})\nonumber\]

Step 4) Write the salt by combing the cations from the base and the anions from the acid. Make sure the charges are balanced in the salt to make it a neutral substance.

\[\mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{SO}_{4}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{Ba}(\mathrm{OH})_{2}(\mathrm{aq}) \rightarrow \mathrm{BaSO}_{4}(\mathrm{aq})+2 \mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{l})\nonumber\]

Antacids

The stomach sometimes produces excess HCl that may cause heartburn.

Antacids are the substances used to neutralize the excess HCl in the stomach.

Fig. 6.7.3 shows antacid tablets. The antacids include Arrhenius bases with very low solubility in water, like Al(OH)3, and Mg(OH)2, or weak bases like CaCO2, and NaHCO3. that react with and neutralize the acid:

\[\begin{aligned}

&\mathrm{Al}(\mathrm{OH})_{3}(\mathrm{~s})+3 \mathrm{HCl}(\mathrm{aq}) \rightarrow \mathrm{AlCl}_{3}(\mathrm{aq})+3 \mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{l}) \\

&\mathrm{Mg}(\mathrm{OH})_{2}(\mathrm{~s})+2 \mathrm{HCl}(\mathrm{aq}) \rightarrow \mathrm{MgCl}_{2}(\mathrm{aq})+2 \mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{l}) \\

&\mathrm{CaCO}_{3}(\mathrm{~s})+2 \mathrm{HCl}(\mathrm{aq}) \rightarrow \mathrm{CaCl}_{2}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{I})+\mathrm{CO}_{2}(\mathrm{~g}) \\

&\mathrm{NaHCO}_{3}(\mathrm{~s})+\mathrm{HCl}(\mathrm{aq}) \rightarrow \mathrm{NaCl}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{I})+\mathrm{CO}_{2}(g)

\end{aligned}\nonumber\]

Side effects of the antacids

The antacids have side effects, e.g., aluminum and calcium-containing antacids may cause constipation. Magnesium-containing antacids have a laxative effect. Some formulations use a mixture of aluminum and magnesium-containing antacids to cancel out the side effect of each other. The calcium-containing antacid is not recommended for persons who tend to develop kidney stones, because the kidney stone is usually a salt of calcium. Sodium-containing antacids may increase the sodium level in the body fluid and may raise the blood pH.

Acid-base titration

The acid-base titration is an analytical process of determining the concentration of acid, called analyte, by neutralizing it with a base of know concentration, called the standard, or vice versa.

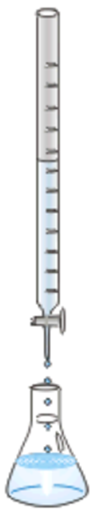

Usually, the base is in a burette and added drop by drop to a known volume of the acid in an Erlenmeyer flask, as illustrated in Fig. 6.7.4. A few drops of an acid-base indicator are mixed with the acid. The indicator changes color at a specific narrow pH range.

- The point when the stoichiometric amount of the base has been added to the acid is called the equivalence point.

- The point when the indicator changes color is the end-point.

Usually, the equivalence point is almost the same as the end-point.

The calculation steps after the titration are usually the following.

- The amount, in moles, of the standard is calculated by multiplying the amount in liters with the molarity of the standard.

- Then, the amount, in moles, of the analyte, is calculated by using the mol-to-mol conversion factor from the balanced chemical equation of the reaction.

- Finally, the molarity of the analyte is calculated by dividing moles by the volume in liters of the analyte.

What is the molarity of the HCl solution if 50.0 mL of the HCl solution requires 42.0 mL of 0.123 M NaOH solution in the titration?

Solution

Step 1) Given: \[[\mathrm{NaOH}]=0.123 \mathrm{~M}=\frac{0.123 \operatorname{~mol} ~N a O H}{1 \mathrm{~NaOH}}\nonumber\]

\[\text{Volume of standard}=42.0 \mathrm{~mL} .=42.0 \mathrm{~mL} \mathrm{~NaOH} \times \frac{1 \mathrm{~L~NaOH}}{1000 \mathrm{~mL} \mathrm{~NaOH}}=0.0420 ~L \mathrm{~NaOH}\nonumber\]

\[\text{Vol. analyte}=50.0 \mathrm{~mL}=50.0 \mathrm{~mL} \mathrm{~HCl} \times \frac{1 \mathrm{~L~HCl}}{1000 \mathrm{~mL} \mathrm{~HCl}}=0.0500 \mathrm{~L~HCl}\nonumber\]

Step 2) Calculate the moles of the standard from the volume and the molarity product.

\begin{equation}

\text { Moles of } \mathrm{~NaOH} \text {~consumed }=0.0420 \mathrm{~L} \mathrm{~NaOH} \times \frac{0.123 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{~NaOH}}{1 \mathrm{~L} \mathrm{~NaOH}}=0.00517 \mathrm{~mol}{ } \mathrm{~NaOH}\nonumber

\end{equation}

Step 3) write the balanced chemical equation of the reaction.

\begin{equation}

\mathrm{HCl}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{NaOH}(\mathrm{aq}) \rightarrow \mathrm{NaCl}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{l})\nonumber\

\end{equation}

Step 4) write the conversion factor for mole of standard to mole of analyte calculation from the equation.

\begin{equation}

\frac{1 \text {mol } \mathrm{~HCl}}{1 \mathrm{~mol } \mathrm{~NaOH}}\nonumber

\end{equation}

Step 5) Calculate the moles of the analyte by multiplying the moles of the standard and the conversion factor.

\begin{equation}

0.00517 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{~NaOH} \times \frac{1 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{~HCl}}{1 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{~NaOH}}=0.00517 \mathrm{~mol} { }\mathrm{~HCl}\nonumber

\end{equation}

Step 6) Calculate the molarity of the analyte by dividing the moles with the volume in liters of the analyte.

\begin{equation}

0.00517 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{~NaOH} \times \frac{1 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{~HCl}}{1 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{~NaOH}}=0.00517 \mathrm{~mol}{ } \mathrm{~HCl}\nonumber

\end{equation}

After learning the steps thoroughly, the calculations can be done in a few steps, as shown in the following.

Calculations: \[\quad 42.0 \mathrm{~mL} \mathrm{~NaOH} \times \frac{1 \mathrm{~L} \mathrm{~NaOH}}{1000 \mathrm{~mL} \mathrm{~NaOH}} \times \frac{0.123 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{~NaOH}}{1 \mathrm{~L} \mathrm{~NaOH}} \times \frac{1 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{~HCl}}{1 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{~NaOH}}=0.00517 \mathrm{~mol}{ } \mathrm{~HCl}\nonumber\]

Molarity of HCl: \[\quad M=\frac{n(\mathrm{mol})}{V(L)}=\frac{0.00517 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{~HCl}}{50.0 \mathrm{~mL} \mathrm{~HCl}} \times \frac{1000 \mathrm{~mL} \mathrm{~HCl}}{1 \mathrm{~L~HCl}}=0.103 \mathrm{~M} { }\mathrm{~HCl}\nonumber\]

What is the molarity of the H2SO4 solution if 50.0 mL of the H2SO4 solution requires 32.3 mL of 0.201 M NaOH solution in the titration?

Solution

Step 1) Given: \begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

&{[\mathrm{NaOH}]=0.201 \mathrm{~M}=\frac{0.201 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{~NaOH}}{1 \mathrm{~L} \mathrm{~NaOH}}} \\

&\text { Vol. standard }=42.0 \mathrm{~mL}=32.3 \mathrm{~mL} \mathrm{~NaOH} \times \frac{1 \mathrm{~L} \mathrm{~NaOH}}{1000 \mathrm{~mL} \mathrm{~NaOH}}=0.0323 \mathrm{~L} \mathrm{~NaOH} \\

&\text { Vol. analyte }=50.0 \mathrm{~mL}=50.0 \mathrm{~mL~HCl} \times \frac{1 \mathrm{~L} \mathrm{~HCl}}{1000 \mathrm{~mL} \mathrm{~HCl}}=0.0500 \mathrm{~L} \mathrm{~HCl}

\end{aligned}\nonumber

\end{equation}

Step 2) Calculate the moles of the standard from the volume and the molarity product.

\begin{equation}

\text { Moles of } \mathrm{~NaOH} \text { consumed }=0.0323 \mathrm{~N} \mathrm{~NaOH} \times \frac{0.201 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{~NaOH}}{1 \mathrm{~L} \mathrm{~NaOH}}=0.00649 \text {~mol } {~NaOH }\nonumber

\end{equation}

Step 3) write the balanced chemical equation of the reaction.

\begin{equation}

\mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{SO}_{4}(\mathrm{aq})+2 \mathrm{NaOH}(\mathrm{aq}) \rightarrow \mathrm{Na}_{2} \mathrm{SO}_{4}(\mathrm{aq})+2 \mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{l})\nonumber

\end{equation}

Step 4) write the conversion factor for the moles of standard to mole of analyte calculation from the equation.

\begin{equation}

\frac{1 \mathrm{~mol}\mathrm{~H}_{2} \mathrm{SO}_{4}}{2 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{~NaOH}}\nonumber

\end{equation}

Step 5) Calculate the moles of the analyte by multiplying the moles of the standard and the conversion factor.

\begin{equation}

0.00649 \text { mol } \mathrm{~NaOH} \times \frac{1 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{~H}_{2} \mathrm{SO}_{4}}{2 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{~NaOH}}=0.00325 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{~H}_{2} {SO}_{4}\nonumber

\end{equation}

Step 6) Calculate the molarity of the analyte by dividing the moles with the volume in liters of the analyte.

\begin{equation}

\text { Concentration of } \mathrm{~H}_{2} \mathrm{SO}_{4}=\frac{0.00325 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{~H}_{2} \mathrm{SO}_{4}}{0.0500 \mathrm{~L} \mathrm{~H}_{2} \mathrm{SO}_{4}}=0.0649 \mathrm{~M} {~H_{2}} SO_{4}\nonumber

\end{equation}

The same calculation in a summary form is in the following.

\[\text {Concentration of} \mathrm{~H}_{2} \mathrm{SO}_{4}=\frac{0.00325 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{~H}_{2} \mathrm{SO}_{4}}{0.0500 \mathrm{~L~H}_{2} \mathrm{SO}_{4}}=0.0649 \mathrm{~M} \mathrm{~H}_{2} \mathrm{SO}_{4}\nonumber\]

\[\text{Moles of} \mathrm{~H}_{2} \mathrm{SO}_{4} =\quad 32.3 \mathrm{~mL} \mathrm{~NaOH} \times \frac{1 \mathrm{~L} \mathrm{~NaOH}}{1000 \mathrm{~mL} \mathrm{~NaOH}} \times \frac{0.201 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{~NaOH}}{1 \mathrm{~L} \mathrm{~NaOH}} \times \frac{1 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{~H}_{2} \mathrm{SO}_{4}}{2 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{~NaOH}}=0.00326 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{} \mathrm{~H}_{2} \mathrm{SO}_{4}\nonumber\]

\[\text{Molarity of} \mathrm{~H}_{2} \mathrm{SO}_{4}: \quad M=\frac{n(\mathrm{~mol})}{V(L)}=\frac{0.00326 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{~H}_{2} \mathrm{SO}_{4}}{50.0 \mathrm{~mL} \mathrm{~H}_{2} \mathrm{SO}_{4}} \times \frac{1000 \mathrm{~mL} \mathrm{~H}_{2} \mathrm{SO}_{4}}{1 \mathrm{~L~H}_{2} \mathrm{SO}_{4}}=0.0649 \mathrm{~M} \mathrm{~H}_{2} \mathrm{SO}_{4}\nonumber\]