8.4.1: Hydrogen's Chemical Properties

- Page ID

- 199687

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Chemical Properties

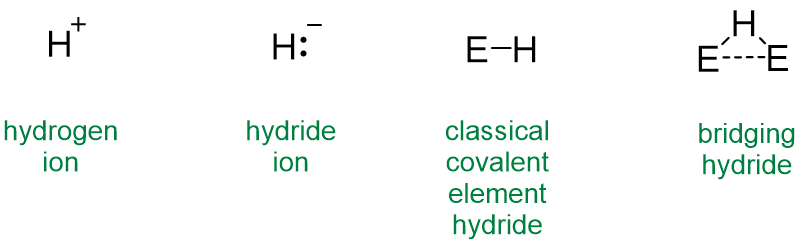

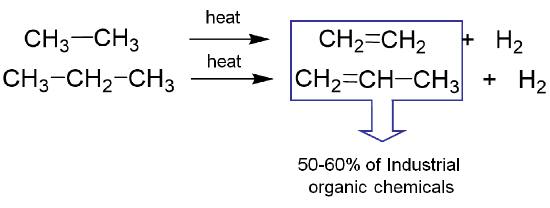

As described in Section 8.1.1.2., hydrogen and helium are distinguished from all other elements in that their valence shell only consists of the 1s orbital. In the case of neutral atomic hydrogen, this orbital is occupied by one electron. Consequently, the chemistry of hydrogen is distinguished by stable bonding arrangements in which the 1s orbital is "filled" by one of the following:

- loss of an electron to give hydrogen ion, H+. In condensed phases these H+ ions are typically stabilized as Lewis base adducts (e.g., in species like H3O+ and NH4+)

- gain of an electron to give hydride ion, H-. This type of bonding adequately explains the behavior of many metal hydrides.

- pairwise sharing of electrons to give covalent E-H bonds that can adequately be described by Lewis theory.

- multicenter sharing of electrons in multicenter covalent bonds, such as those in hydrides that bridge two or more atoms.

- contributing electrons and orbitals to the band structure of a solid state lattice. This is common in interstitial/metallic hydrides.

The first four of these possibilities are summarized in Scheme \(\sf{\PageIndex{I}}\).

Scheme \(\sf{\PageIndex{I}}\). Common bonding arrangements for hydrogen. The E-H and E---E bonds in the bridging hydride represent sharing of two or more electrons among the three atoms.

Elemental Hydrogen

At room temperature and pressure, elemental hydrogen exists in the form of dihydrogen, H2. Dihydrogen is a colorless, odorless gas that finds wide industrial application.

Preparation

In the laboratory H2 may be prepared by the electrolytic or chemical reduction of water involving the half reaction.

\[\sf{2H_2O + 2e^- \rightarrow H_2 + OH^-} \nonumber \]

Such reductions are commonly carried out on acidic solutions since the potentials required are lower, as may be seen from the Pourbaix diagram for hydrogen given in Figure \(\sf{\PageIndex{2}}\).

A common method is to add Zn to a solution of hydrochloric acid.

\[ \sf{2~H^+(aq)~~+~~Zn(s)~\rightarrow H_2(g)~~+~~Zn^{2+}(aq) } \nonumber \]

In electrolysis the electrons come from the oxidation of water at the anode so that hydrogen production involves water splitting.

\[ \sf{2~H_2O(l)~~ \rightarrow~~2~H_2(g)~~+~~O_2(g)} \nonumber \]

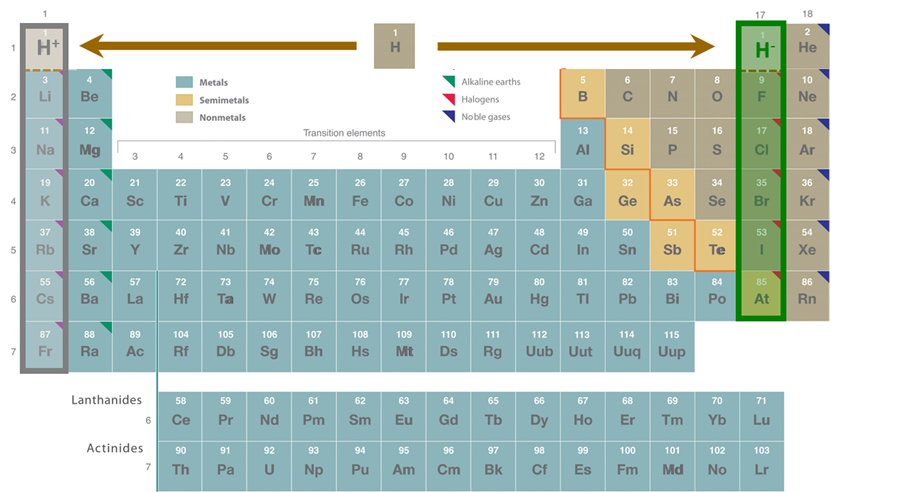

Industrially it is more common to produce hydrogen via steam reforming of methane and other hydrocarbons.

\[ \sf{CH_4(g)~~+~~H_2O(g)~\overset{Ni}{\longrightarrow}~CO(g)~~+~~3~H_2(g)~~~~(steam~reforming)} \nonumber \]

In this process the formally C4- of methane acts as the reductant. The product of steam reforming is a mixture of CO and H2.. Similar mixtures can also be produced by the anaerobic thermal decomposition of organics and in coal gasification reactions. In all cases they are called syngas (i.e., synthesis gas) since they can be used in other industrial syntheses. Its CO component is capable of acting as a reductant, so additional hydrogen can be produced from it via the water-gas shift reaction.

\[ \sf{CO(g)~~+~~H_2O(g)~\rightarrow~CO_2(g)~~+~~H_2(g)~~~~(water~gas~shift)} \nonumber \]

The "cracking" of hydrocarbons also serves as a source of industrially-produced hydrogen, although the alkenes so produced are perhaps even more important as the source of a majority of commodity organic chemicals.

Much of the hydrogen produced industrially is consumed in the Haber-Bosch synthesis of ammonia. The quantities involved are such that hydrogen production for this purpose has been variously estimated to account for 1-2% of global energy consumption.

\[\sf{N_2(g)~~+~~3~H_2(g)~\rightarrow~2NH_3(g)~~~~(Haber-Bosch~process)} \nonumber \]

Dihydrogen has also been considered for use as a fuel since its combustion is both highly exothermic and green, giving rise only to water.

\[\sf{2~H_2(g)~~+~~O_2(g)~\rightarrow~2H_2O(g)} \nonumber \]

One of the major obstacles to the implementation of hydrogen as a fuel is that its production by steam reforming and the water-gas shift reaction generates CO and CO2, and costs more energy than is gained from its combustion. For this reason, photocatalytic water splitting is considered one of the holy grails of energy research.

Compounds of hydrogen

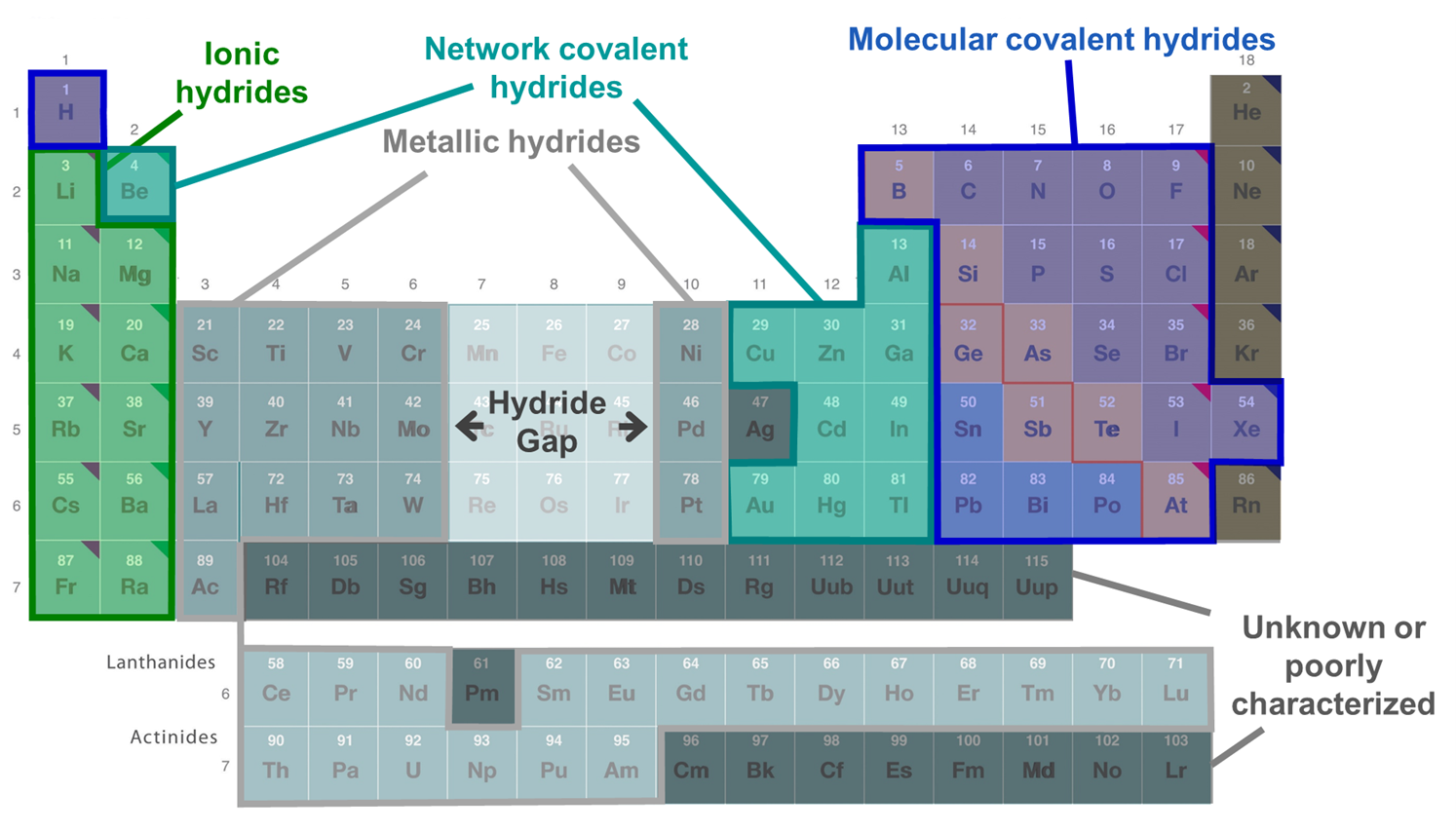

Compounds of hydrogen are called hydrides whether or not they contain hydride anion. There are three main types of hydrides - ionic, covalent, and interstitial hydrides. As shown in the periodic table of hydrides given in Figure \(\sf{\PageIndex{3}}\), interstitial or metallic hydrides are formed by some transition metals, while ionic hydrides are mainly formed by more electropositive metals and covalent hydrides by the nonmetals. The hydrides of Be, some metalloids, and some post-transition metals are said to be intermediate hydrides since they form network covalent structures (sometimes in addition to molecular ones) and tend to function as bases and hydride donors like the ionic hydrides. Not all of the transition metals are known to form hydrides. No hydrides are known for the transition metals of groups 7-9, which are said to constitute the hydride gap.

Figure \(\sf{\PageIndex{3}}\). Distribution of the different types of element hydrides across the periodic table. The figure is adapted from the Periodic Table at https://chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/General_Chemistry/Map%3A_Chemistry_-_The_Central_Science_(Brown_et_al.)/02._Atoms%2C_Molecules%2C_and_Ions/2.5%3A_The_Periodic_Table

Figure \(\sf{\PageIndex{3}}\). Distribution of the different types of element hydrides across the periodic table. The figure is adapted from the Periodic Table at https://chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/General_Chemistry/Map%3A_Chemistry_-_The_Central_Science_(Brown_et_al.)/02._Atoms%2C_Molecules%2C_and_Ions/2.5%3A_The_Periodic_TableIonic hydrides (a.k.a. saline hydrides)

Ionic hydrides are metal salts of the hydride anion, H-. These are formed by the alkali metals and all the alkaline earth metals except Be. These are typically prepared by direct reaction of the metal and hydrogen.

\[\sf{2~M(s)~~+~~H_2(g)~~\overset{\Delta}{\longrightarrow}~~2~MH(s)~~~~~(M~=~Li,~Na,~K,~Rb)} \nonumber \]

\[\sf{M(s)~~+~~H_2(g)~~\overset{\Delta}{\longrightarrow}~~2~MH_2(s)~~~~~(M~=~Mg,~Ca,~Sr,~Ba)} \nonumber \]

As salts of H-, ionic hydrides form ionic lattices (the NaCl structure is common for MH, the Rutile and PbI2 for MH2).

Chemically ionic hydrides act as

- reducing agents towards metal oxides. For example

\[\sf{2CaH_2(s)~~+~~TiO_2 (l)~\rightarrow~2CaO(s)~~+~~Ti(s)~~+~~2~H_2(aq)} \nonumber \]

- strong bases towards protic E-H bonds. All react exothermically with water to liberate hydrogen gas.

\[\sf{MH(s)~~+~~H_2O(l)~\rightarrow~M^+(aq)~~+~~H_2(g)~~+~~OH^-(aq)} \nonumber \]

For this reason CaH2 is widely used as a drying agent for organic solvents.

Reactive metal hydrides may also be used to deprotonate reactive C-H bonds:

\[\sf{NaH(s)~~+~~CH_3C \equiv C-H(g)~\rightarrow~CH_3C \equiv C:^-Na^+~~+~~H_2(g)} \nonumber \]

The H:- ion in an ionic hydride may in principle act as a nucleophile. However, in practice this application is limited to the less reactive and consequently more selective hydrides of aluminum and boron, both of which are usually classified as intermediate hydrides on account of the covalent character of their E-H bonds.

Covalent and intermediate hydrides

Covalent molecular hydrides are formed by the nonmetals, metalloids, and many post-transition metals. The chemical and physical properties they possess vary across the main group and depend somewhat on the row and whether the element hydride is electron deficient, electron rich, or electron precise. Specifically,

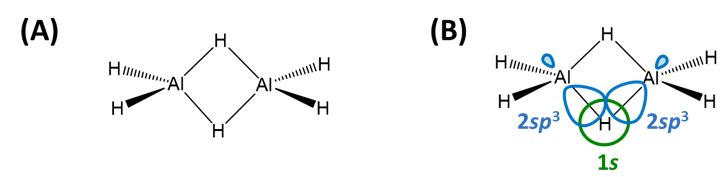

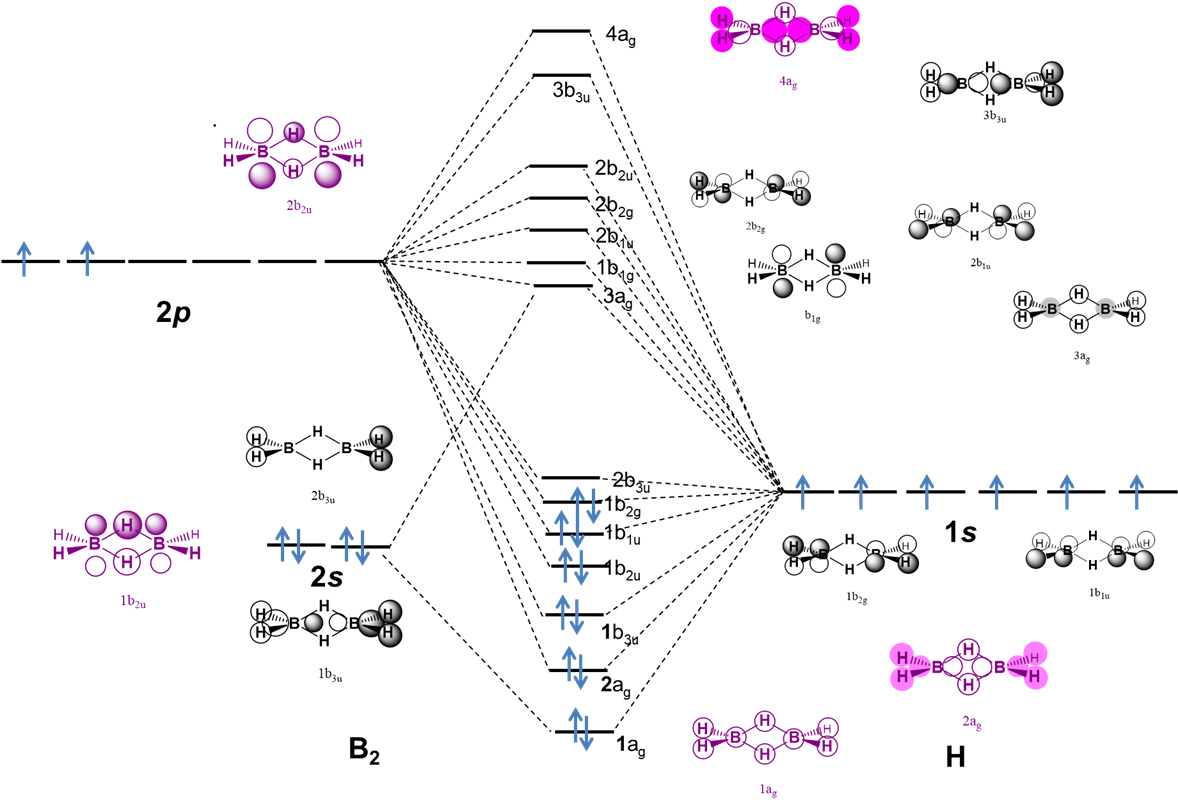

Electron deficient hydrides are those of Be and the group 13 elements (B, Al, Ga, In, and Tl) for which the neutral monomeric element hydride (BeH2, BH3, AlH3, GaH3, InH3, and TlH3 does not possess enough electrons to satisfy the octet rule. Thus these hydrides commonly form dimers (B, Al, Ga, In, Tl) or polymers (Be) held together by bridging E-H-E bonds (Scheme \(\sf{\PageIndex{IIA}}\)). These E-H-E bonds are explained as three-center two-electron bonds in valence bond theory )Scheme \(\sf{\PageIndex{IIB}}\)), but may also be described in terms of molecular orbitals (Note \(\sf{\PageIndex{1}}\)).

Scheme \(\sf{\PageIndex{II}}\). (A) Bridging E-H-E bonds in Al2H6 and (B) their valence bond description in terms of overlap between the H 1s and Al sp3 orbitals.

Electron precise and electron rich hydrides are formed by C, N, O, F, and their heavier cogeners. The E-H bonds in these may be described as classical two-center two-electron E-H bonds of Lewis Theory. The electron precise and electron rich hydrides are distinguished in that the electron rich hydrides possess lone pair electrons, while electron precise hydrides do not. In other words,

- electron precise hydrides are those of the group 14 elements, and include the alkanes, alkenes, and alkynes of carbon along with SiH4, GeH4, SnH4, and PbH4, of which the hydride adducts of group 13 EH3 compounds like BH4- and AlH4- are analogues.

- electron rich hydrides are NH3, H2O,, HF and their heavier analogues (PH3, H2S, HCl, etc.). Regardless of the hydride's classification, the stability of element hydrides decreases down a group. For example, among the group 14 elements, it follows the order CH4 > SiH4 > GeH4 > SnH4 > PbH4. The same is true of compounds possessing E-E bonds so that while a vast number of alkanes are known, there are relatively few silanes, fewer germanes, and only the organic analogs of stannane are known (such as (CH3)3Sn-Sn(CH3)3).

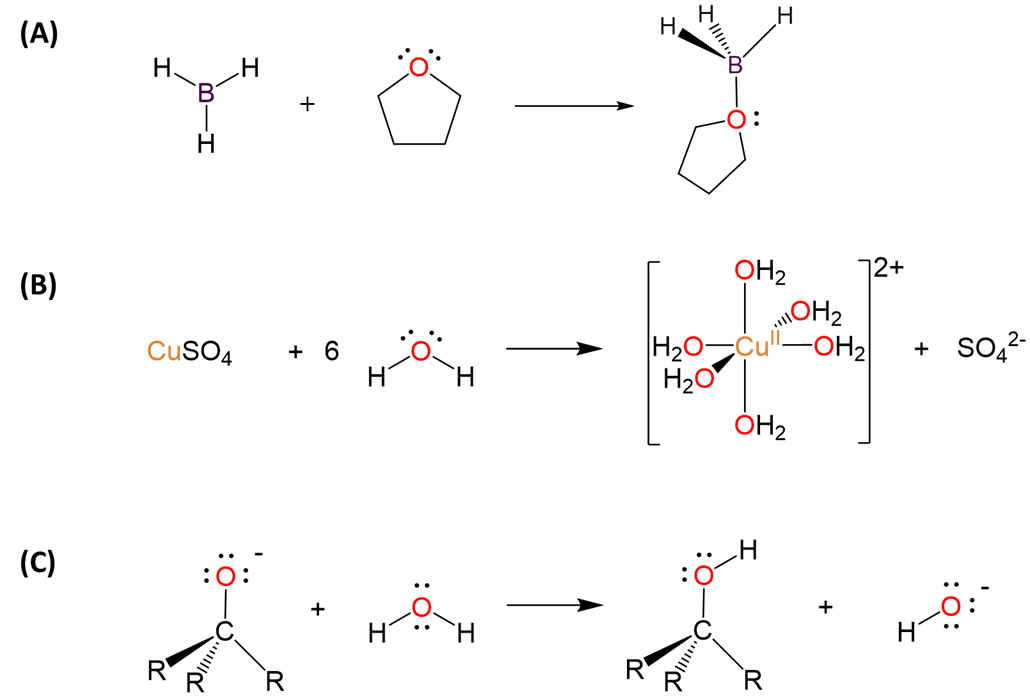

The distinction between electron precise and electron rich hydrides is important mainly in thinking about the Lewis acid-base properties of the element hydrides. As illustrated in Scheme \(\sf{\PageIndex{III}}\), electron deficient hydrides tend to function as Lewis acids and electron rich hydrides as Lewis bases and Brønsted acids.

Scheme \(\sf{\PageIndex{III}}\). In the absence of extremely strong acids or bases, electron-deficient hydrides like BH3 tend to act as (A) Lewis acids in forming adducts with bases like THF, while electron rich hydrides can act as (B) Lewis bases through their lone pairs, as water does with Cu2+ when anhydrous CuSO4 is dissolved in water, or as (C) Brønsted acids, as water does when it is used to quench the alkoxide product of a nucleophilic addition reaction.

The reactivity of electron precise hydrides depends on the characteristics of E. For example, while most alkanes do not act as Lewis acids at the carbon atom, row 3 and heavier electron precise hydrides can form trigonal bipyramidal adducts.

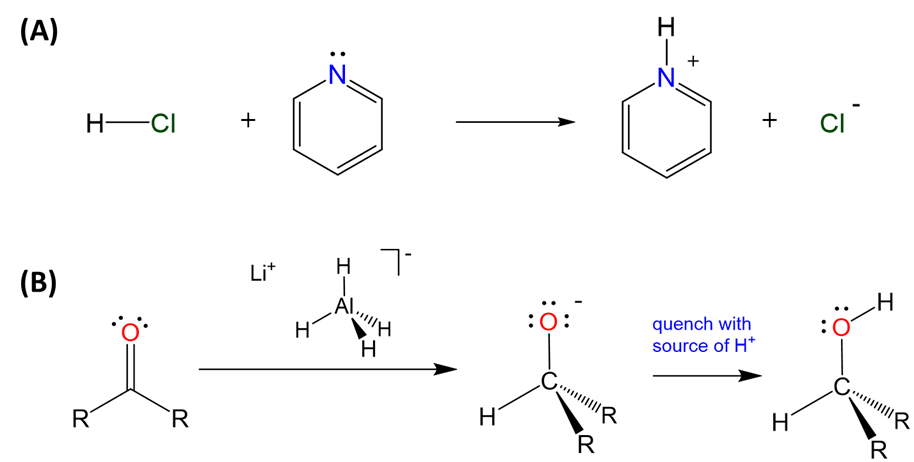

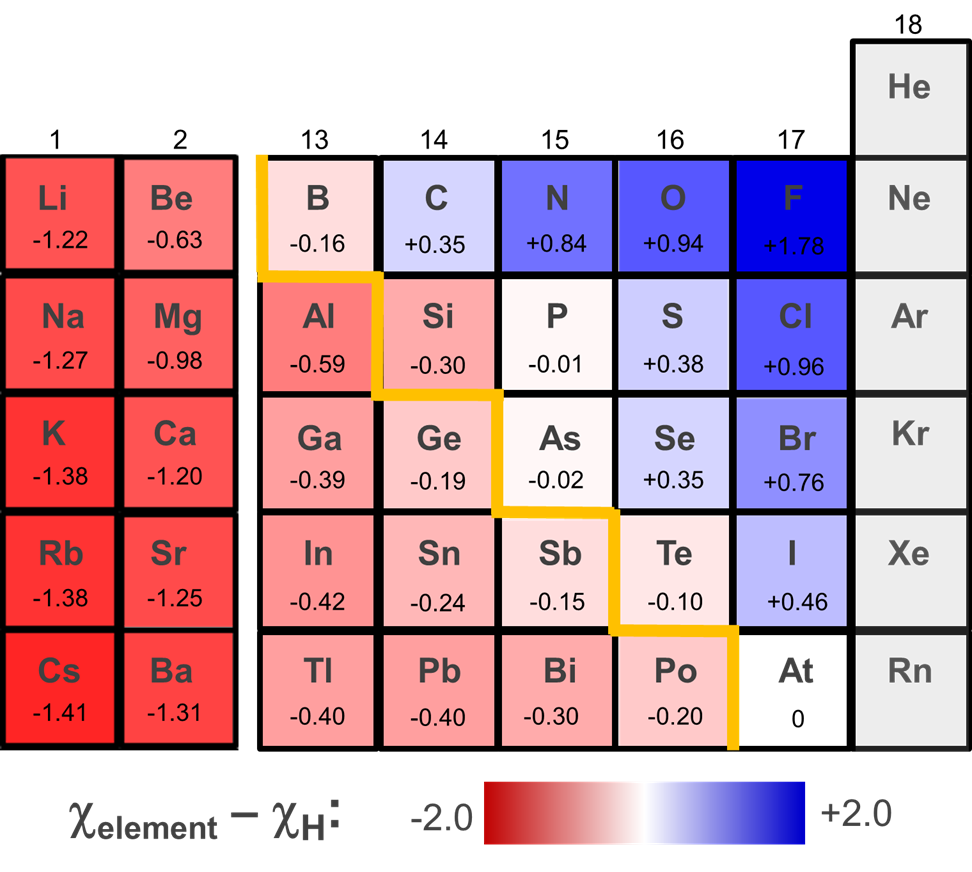

Moreover, all element hydrides - whether electron deficient, precise, or rich - can function as a weak Brønsted acids or hydride donors depending on the polarity of the E-H bond. Hydrides in which hydrogen is bound to an electron rich and electronegative element tend to act as Brønsted acids, while those involving more electropositive elements tend to function as hydride donors, as illustrated in Scheme \(\sf{\PageIndex{IV}}\).

Scheme \(\sf{\PageIndex{IV}}\). (A) The electron rich hydride of chlorine acts as a Brønsted acid in forming a pyridinium complex while (B) the relatively electropositive hydride in tetrahydroaluminate is widely used as a hydride donor in organic chemistry, as illustrated by the use of lithium aluminum hydride to form alcohols from ketones.

The ability of a given element hydride to function as an acid or hydride donor may be modified by a number of factors. One of these is the solvation energy of the species formed. According to Figure \(\sf{\PageIndex{4}}\), Germane (GeH4) might be expected to function as a hydride donor. However, it can be deprotonated in liquid ammonia, likely because of the large solvation energy of the resulting H+ ion.

\[\sf{GeH_4~~\overset{NH_3(l)}{\longrightarrow}~~H^+(solv.)~~+~~GeH_3^-(solv.)} \nonumber \]

Electronic factors that affect the stability of the element hydride's conjugate acid or base forms also play a role. For example, carbon-hydrogen bonds are normally very weakly acidic but can act as strong Brønsted acids when the resulting anion is highly stabilized or as a hydride donor when the resulting cation is highly stabilized. This is illustrated by the well-known ability of C-H bonds to function as Brønsted acids, hydride donors, or neither depending on the electron-richness of the carbon center and the stability of the resulting structure (Scheme \(\sf{\PageIndex{V}}\)).

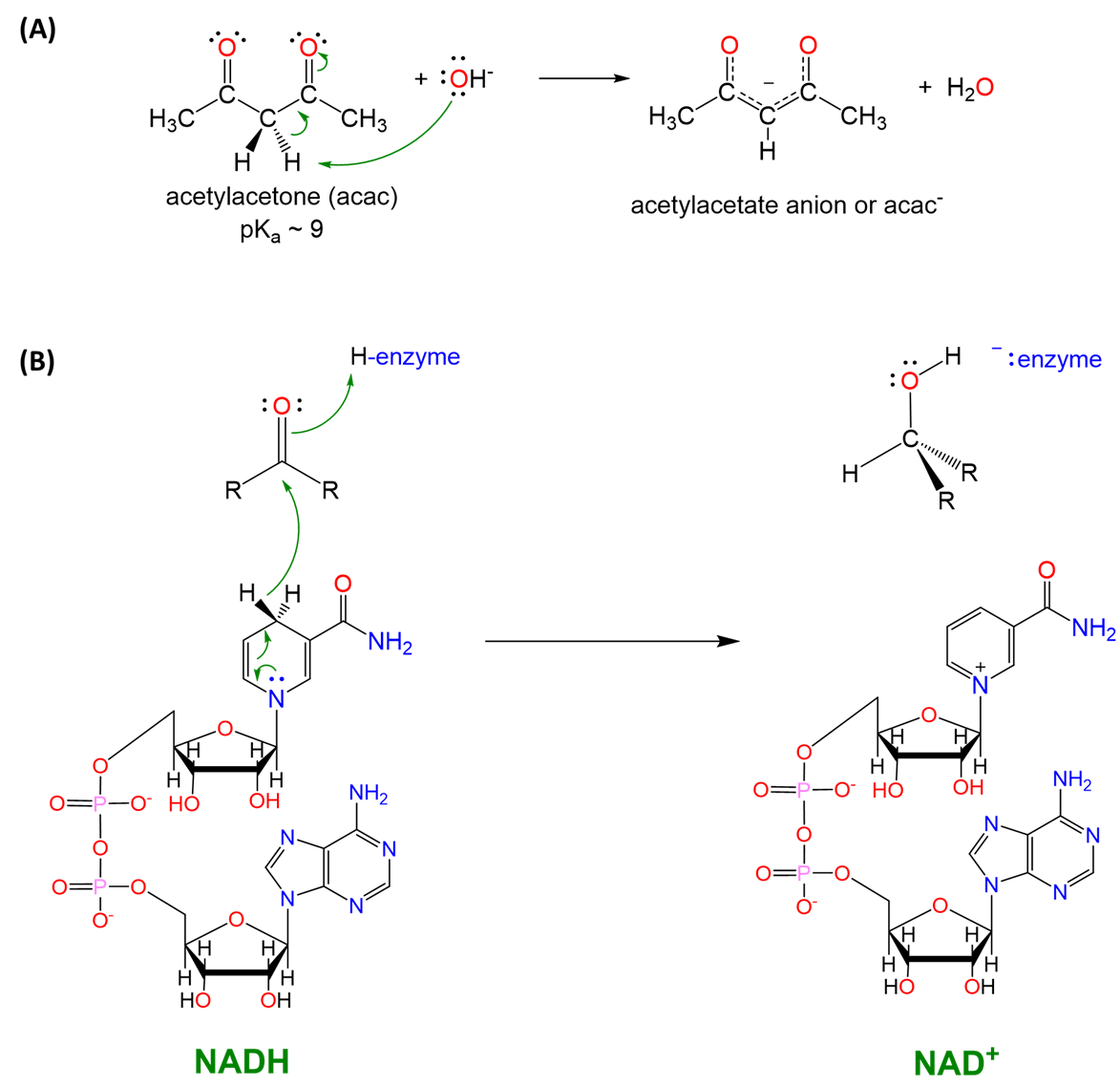

Scheme \(\sf{\PageIndex{V}}\). (A) enolate chemistry such as that used in the formation of acetylacetate (acac) ligands is based on the ability of C-H bonds \(\sf{\alpha}\) to a carbonyl to act as acids, and (B) a C-H bond of NADH functions as a hydride donor in biochemical systems. Notice the similarity in reactivity of the C-H hydride in NADH and the Al-H in LiAlH4 shown in Scheme \(\sf{\PageIndex{IV}}\).

Additional aspects of the acid-base chemistry of the element hydrides are described in 6: Acid-Base and Donor-Acceptor Chemistry, as is hydrogen's ability to form hydrogen bonds.

Interstitial hydrides (a.k.a. metallic hydrides)

In interstitial or metallic hydrides, hydrogen dissolves in a metal to form nonstoichiometric compounds (solid solutions) of formula MHn. They are called metallic hydrides since they possess the typical metallic properties of luster, hardness, and conductivity and are called interstitial hydrides because the H occupies interstices in an FCC, HCP, or BCC metal lattice, as illustrated schematically in Figure \(\sf{\PageIndex{5}}\).

The process of interstitial hydride formation is reversible, and metals can dissolve varying amounts of hydrogen depending on the number of interstices available. Because of this, interstitial hydrides have been considered as storage materials for hydrogen.

The B-H-B bonds in diborane may also be explained using a molecular orbital description, as illustrated by the qualitative MO diagram in Figure \(\sf{\PageIndex{6}}\).

References

1. Møller, K. T.; Jensen, T. R.; Akiba, E.; Li, H.-w., Hydrogen - A sustainable energy carrier. Progress in Natural Science: Materials International 2017, 27 (1), 34-40.

Contributors and Attributions

Stephen Contakes, Westmont College