Radiobiology

- Page ID

- 50764

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Radiobiology is an interdisciplinary field of science that focuses on the biological effects of all types of radiation. In this section, we begin to explore the kinds of radiation that originate from nuclei, usually classified as "ionizing radiation". Over the next chapters we'll investigate different types of radiation that originate outside the nucleus, providing the foundation that biologist need to understand radiobiology. We'll see which types are dangerous, which characteristics make them appropriate as biological tracers or in radiotherapy, and how they are detected.

This is a complex field, so we should start at the beginning.

Detection of Radiation

Just prior to the turn of the twentieth century, additional observations were made which contradicted parts of Dalton’s atomic theory. The French physicist Henri Becquerel (1852 to 1928) discovered by accident that compounds of uranium and thorium emitted rays which, like rays of sunlight, could darken photographic films. Becquerel’s rays differed from light in that they could even pass through the black paper wrappings in which his films were stored. A modern radiobiologist would note that these particles may be capable of breaking bonds in important cell components, because they carry enough energy to cause chemical changes in photographic films.

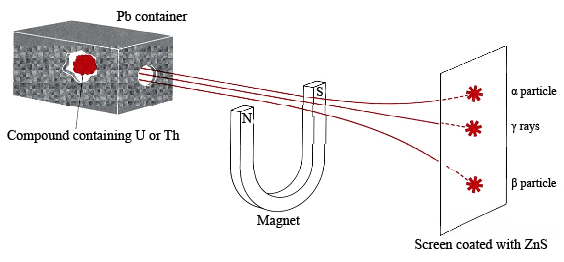

Although themselves invisible to the human eye, the rays could be detected easily because they produced visible light when they struck phosphors such as impure zinc sulfide. Such luminescence is similar to the glow of a psychedelic poster when invisible ultraviolet (black light) rays strike it. Further experimentation showed that if the rays were allowed to pass between the poles of a magnet, they could be separated into the three groups shown in the following figure, or in a YouTube Video

Properties of α, β and γ Particles

Because little or nothing was known about these rays, they were labeled with the first three letters of the Greek alphabet. Upon passing through the magnetic field, the alpha rays (α rays) were deflected slightly in one direction, beta rays (β rays) were deflected to a much greater extent in the opposite direction, and gamma rays (γ rays) were not deflected at all. Deflection by a magnet is a characteristic of electrically charged particles (as opposed to rays of light). From the direction and extent of deflection it was concluded that the β particles had a negative charge and were much less massive than the positively charged α particles. The γ rays did not behave as electrically charged particles would, and so the name rays was retained for them. Taken together the α particles, β particles, and γ rays were referred to as radioactivity, and the compounds which emitted them as radioactive.

The three types of particle differ greatly in penetrating power. While γ particles may penetrate several millimeters of lead, β particles are may penetrate 1 mm of aluminum, but α particles don't penetrate thin paper, or a centimeter or two of air. The high penetrating power of γs does not make them more dangerous, because if they penetrate matter they don't cause changes in it. On the other hand, if an α source is a few inches away, it is not harmful at all; but if an α emitter like radon is inhaled, the &alpha particles are very dangerous. Because they don't penetrate matter, their energy is absorbed in the alveoli of the lung where it causes molecular damage, sometimes leading to lung cancer.

Transmutation

Study of radioactive compounds by the French chemist Marie Curie (1867 to 1934) revealed the presence of several previously undiscovered elements (radium, polonium, actinium, and radon).

These elements, and any compounds they formed, were intensely radioactive. When thorium and uranium compounds were purified to remove the newly discovered elements, the level of radioactivity decreased markedly. It increased again over a period of months or years, however, because radioactive decay led to formation of additional radioactive elements. Even if the uranium or thorium compounds were carefully protected from contamination, it was possible to find small quantities of radium, polonium, actinium, or radon in them after such a time.

To chemists, who had been trained to accept Dalton’s indestructible atoms, these results were intellectually distasteful. The inescapable conclusion was that some of the uranium or thorium atoms were spontaneously changing their structures and becoming atoms of the newly discovered elements. A change in atomic structure which produces a different element is called transmutation. Transmutation of uranium into the more radioactive elements could explain the increased emission of radiation by a carefully sealed sample of a uranium compound. During these experiments with radioactive compounds it was observed that minerals containing uranium or thorium always contained lead as well. This lead apparently resulted from further transmutation of the highly radioactive elements radium, polonium, actinium, and radon. The lead found in uranium ores always had a significantly lower atomic weight than lead from most other sources (as low as 206.4 compared with 207.2, the accepted value). Lead associated with thorium always had an unusually high atomic weight. Nevertheless, all three forms of lead had the same chemical properties. Once mixed together, they could not be separated. Such results, as well as the reversed order of elements such as Ar and K in the periodic table, implied that atomic weight is not the fundamental determinant of chemical behavior.

Marie Curie coined the term "radioactivity", and was the first person honored with two Nobel Prizes (1903 in Physics for expanding the early discoveries of Becquerel, and 1911 in Chemistry for the discovery of radium and polonium), and the first female professor at the University of Paris. She died of aplastic anemia, probably caused by exposure to radiation. The harmful effects of radiation were not appreciated during her lifetime.

From ChemPRIME: 4.7: Radiation

Contributors and Attributions

Ed Vitz (Kutztown University), John W. Moore (UW-Madison), Justin Shorb (Hope College), Xavier Prat-Resina (University of Minnesota Rochester), Tim Wendorff, and Adam Hahn.