4.3: Covalent Compounds: Formulas and Names

- Page ID

- 83067

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Skills to Develop

- Determine the chemical formula of a simple covalent compound from its name.

- Determine the name of a simple covalent compound from its chemical formula.

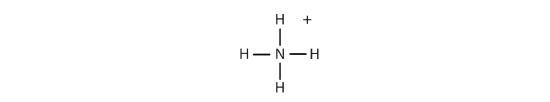

What elements make covalent bonds? Covalent bonds form when two or more nonmetals combine. For example, both hydrogen and oxygen are nonmetals, and when they combine to make water, they do so by forming covalent bonds. Nonmetal atoms in polyatomic ions are joined by covalent bonds, but the ion as a whole participates in ionic bonding. For example, ammonium chloride has ionic bonds between a polyatomic ion, \(NH_4^+\), and \(Cl^−\) ions, but within the ammonium ion, the nitrogen and hydrogen atoms are connected by covalent bonds:

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Is each compound formed from ionic bonds, covalent bonds, or both?

- \(Na_2O\)

- \(Na_3PO_4\)

- \(N_2O_4\)

SOLUTION

- The elements in \(Na_2O\) are a metal and a nonmetal, which form ionic bonds.

- Because sodium is a metal and we recognize the formula for the phosphate ion (see Table 3.1), we know that this compound is ionic. However, polyatomic ions are held together by covalent bonds, so this compound contains both ionic and covalent bonds.

- The elements in \(N_2O_4\) are both nonmetals, rather than a metal and a nonmetal. Therefore, the atoms form covalent bonds.

The chemical formulas for covalent compounds are referred to as molecular formulas because these compounds exist as separate, discrete molecules. Typically, a molecular formula begins with the nonmetal that is closest to the lower left corner of the periodic table, except that hydrogen is almost never written first (H2O is the prominent exception). Then the other nonmetal symbols are listed. Numerical subscripts are used if there is more than one of a particular atom. For example, we have already seen CH4, the molecular formula for methane.

Naming binary (two-element) covalent compounds is similar to naming simple ionic compounds. The first element in the formula is simply listed using the name of the element. The second element is named by taking the stem of the element name and adding the suffix -ide. A system of numerical prefixes is used to specify the number of atoms in a molecule. Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) lists these numerical prefixes. Normally, no prefix is added to the first element’s name if there is only one atom of the first element in a molecule. If the second element is oxygen, the trailing vowel is usually omitted from the end of a polysyllabic prefix but not a monosyllabic one (that is, we would say “monoxide” rather than “monooxide” and “trioxide” rather than “troxide”).

| Number of Atoms in Compound | Prefix on the Name of the Element |

|---|---|

| 1 | mono-* |

| 2 | di- |

| 3 | tri- |

| 4 | tetra- |

| 5 | penta- |

| 6 | hexa- |

| 7 | hepta- |

| 8 | octa- |

| 9 | nona- |

| 10 | deca- |

| *This prefix is not used for the first element’s name. | |

Let us practice by naming the compound whose molecular formula is CCl4. The name begins with the name of the first element—carbon. The second element, chlorine, becomes chloride, and we attach the correct numerical prefix (“tetra-”) to indicate that the molecule contains four chlorine atoms. Putting these pieces together gives the name carbon tetrachloride for this compound.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Write the molecular formula for each compound.

- chlorine trifluoride

- phosphorus pentachloride

- sulfur dioxide

- dinitrogen pentoxide

SOLUTION

If there is no numerical prefix on the first element’s name, we can assume that there is only one atom of that element in a molecule.

- ClF3

- PCl5

- SO2

- N2O5 (The di- prefix on nitrogen indicates that two nitrogen atoms are present.)

Note

Because it is so unreactive, sulfur hexafluoride is used as a spark suppressant in electrical devices such as transformers.

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Write the name for each compound.

- BrF5

- S2F2

- CO

SOLUTION

- bromine pentafluoride

- disulfur difluoride

- carbon monoxide

For some simple covalent compounds, we use older common names rather than systematic names. We have already encountered these compounds, but we list them here explicitly:

- H2O: water

- NH3: ammonia

- CH4: methane

Methane is the simplest organic compound. Organic compounds are compounds with carbon atoms and are named by a separate nomenclature system that we will introduce in Section 4.6 "Introduction to Organic Chemistry".

Concept Review Exercises

- How do you recognize a covalent compound?

- What are the rules for writing the molecular formula of a simple covalent compound?

- What are the rules for naming a simple covalent compound?

Answers

- A covalent compound is usually composed of two or more nonmetal elements.

- It is just like an ionic compound except that the element further down and to the left on the periodic table is listed first and is named with the element name.

- Name the first element first and then the second element by using the stem of the element name plus the suffix -ide. Use numerical prefixes if there is more than one atom of the first element; always use numerical prefixes for the number of atoms of the second element.

Key Takeaways

- The chemical formula of a simple covalent compound can be determined from its name.

- The name of a simple covalent compound can be determined from its chemical formula.

Exercises

-

Identify whether each compound has ionic bonds, covalent bonds, or both.

- Na3PO4

- K2O

- COCl2

- CoCl2

-

Write the name for each covalent compound.

- SiF4

- NO2

- CS

- P2O5

-

Write the formula for each covalent compound.

- iodine trichloride

- disulfur dibromide

- arsenic trioxide

- xenon hexafluoride

-

Write the three covalent compounds introduced in this chapter that have common rather than systematic names.

Answers

-

- both

- ionic

- covalent

- ionic

-

- silicon tetrafluoride

- nitrogen dioxide

- carbon monosulfide

- diphosphorus pentoxide

3.

- ICl3

- S2Br2

- AsO3

- XeF6

Contributors

- Anonymous