7.2: Coordination Chemistry of Transition Metals

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 122540

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)↵

Learning Objectives

- List the defining traits of coordination compounds

- Describe the structures of complexes containing monodentate and polydentate ligands

- Use standard nomenclature rules to name coordination compounds

- Explain and provide examples of geometric and optical isomerism

- Identify several natural and technological occurrences of coordination compounds

The hemoglobin in your blood, the chlorophyll in green plants, vitamin \(B_{12}\), and the catalyst used in the manufacture of polyethylene all contain coordination compounds. Ions of the metals, especially the transition metals, are likely to form complexes. Many of these compounds are highly colored (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). In the remainder of this chapter, we will consider the structure and bonding of these remarkable compounds.

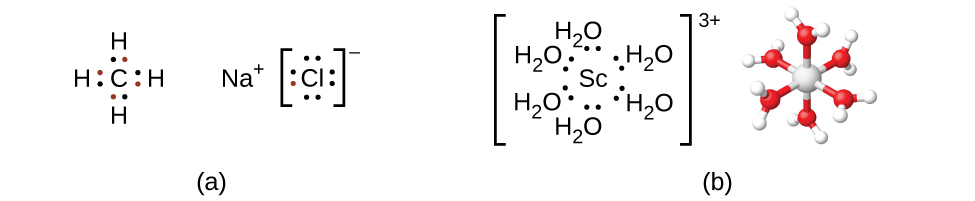

Remember that in most main group element compounds, the valence electrons of the isolated atoms combine to form chemical bonds that satisfy the octet rule. For instance, the four valence electrons of carbon overlap with electrons from four hydrogen atoms to form CH4. The one valence electron leaves sodium and adds to the seven valence electrons of chlorine to form the ionic formula unit NaCl (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). Transition metals do not normally bond in this fashion. They primarily form coordinate covalent bonds, a form of the Lewis acid-base interaction in which both of the electrons in the bond are contributed by a donor (Lewis base) to an electron acceptor (Lewis acid). The Lewis acid in coordination complexes, often called a central metal ion (or atom), is often a transition metal or inner transition metal, although main group elements can also form coordination compounds. The Lewis base donors, called ligands, can be a wide variety of chemicals—atoms, molecules, or ions. The only requirement is that they have one or more electron pairs, which can be donated to the central metal. Most often, this involves a donor atom with a lone pair of electrons that can form a coordinate bond to the metal.

The coordination sphere consists of the central metal ion or atom plus its attached ligands. Brackets in a formula enclose the coordination sphere; species outside the brackets are not part of the coordination sphere. The coordination number of the central metal ion or atom is the number of donor atoms bonded to it. The coordination number for the silver ion in [Ag(NH3)2]+ is two (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). For the copper(II) ion in [CuCl4]2−, the coordination number is four, whereas for the cobalt(II) ion in [Co(H2O)6]2+ the coordination number is six. Each of these ligands is monodentate, from the Greek for “one toothed,” meaning that they connect with the central metal through only one atom. In this case, the number of ligands and the coordination number are equal.

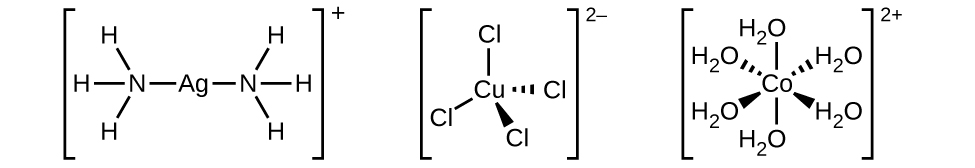

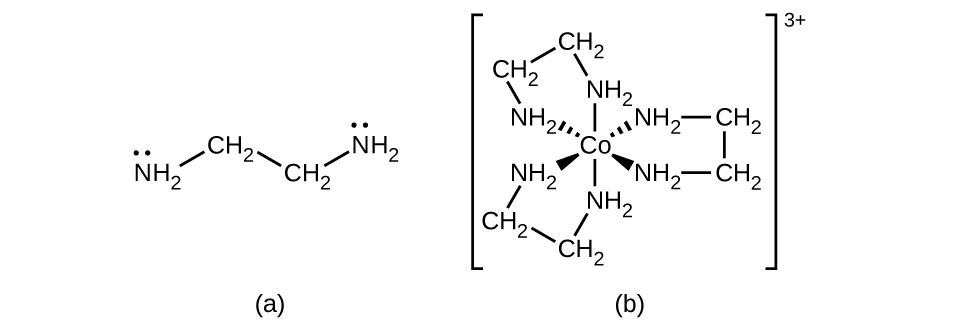

Many other ligands coordinate to the metal in more complex fashions. Bidentate ligands are those in which two atoms coordinate to the metal center. For example, ethylenediamine (en, H2NCH2CH2NH2) contains two nitrogen atoms, each of which has a lone pair and can serve as a Lewis base (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). Both of the atoms can coordinate to a single metal center. In the complex [Co(en)3]3+, there are three bidentate en ligands, and the coordination number of the cobalt(III) ion is six. The most common coordination numbers are two, four, and six, but examples of all coordination numbers from 1 to 15 are known.

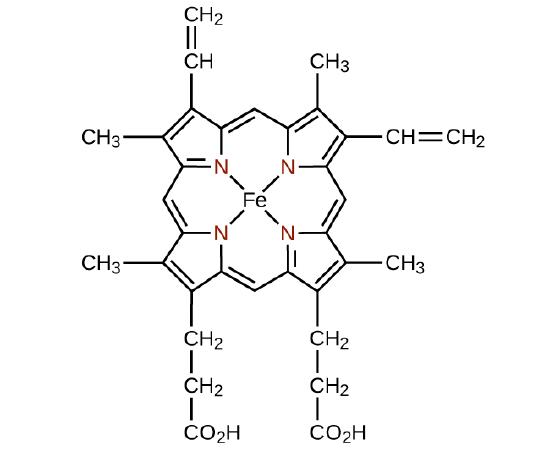

Any ligand that bonds to a central metal ion by more than one donor atom is a polydentate ligand (or “many teeth”) because it can bite into the metal center with more than one bond. The term chelate (pronounced “KEY-late”) from the Greek for “claw” is also used to describe this type of interaction. Many polydentate ligands are chelating ligands, and a complex consisting of one or more of these ligands and a central metal is a chelate. A chelating ligand is also known as a chelating agent. A chelating ligand holds the metal ion rather like a crab’s claw would hold a marble. Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) showed one example of a chelate and the heme complex in hemoglobin is another important example (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)). It contains a polydentate ligand with four donor atoms that coordinate to iron.

Polydentate ligands are sometimes identified with prefixes that indicate the number of donor atoms in the ligand. As we have seen, ligands with one donor atom, such as NH3, Cl−, and H2O, are monodentate ligands. Ligands with two donor groups are bidentate ligands. Ethylenediamine, H2NCH2CH2NH2, and the anion of the acid glycine, \(\ce{NH2CH2CO2-}\) (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)) are examples of bidentate ligands. Tridentate ligands, tetradentate ligands, pentadentate ligands, and hexadentate ligands contain three, four, five, and six donor atoms, respectively. The heme ligand (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)) is a tetradentate ligand.

The Naming of Complexes

The nomenclature of the complexes is patterned after a system suggested by Alfred Werner, a Swiss chemist and Nobel laureate, whose outstanding work more than 100 years ago laid the foundation for a clearer understanding of these compounds. The following five rules are used for naming complexes:

- If a coordination compound is ionic, name the cation first and the anion second, in accordance with the usual nomenclature.

- Name the ligands first, followed by the central metal. Name the ligands alphabetically. Negative ligands (anions) have names formed by adding -o to the stem name of the group (e.g., Table \(\PageIndex{1}\). For most neutral ligands, the name of the molecule is used. The four common exceptions are aqua (H2O), amine (NH3), carbonyl (CO), and nitrosyl (NO). For example, name [Pt(NH3)2Cl4] as diaminetetrachloroplatinum(IV).

- If more than one ligand of a given type is present, the number is indicated by the prefixes di- (for two), tri- (for three), tetra- (for four), penta- (for five), and hexa- (for six). Sometimes, the prefixes bis- (for two), tris- (for three), and tetrakis- (for four) are used when the name of the ligand already includes di-, tri-, or tetra-, or when the ligand name begins with a vowel. For example, the ion bis(bipyridyl)osmium(II) uses bis- to signify that there are two ligands attached to Os, and each bipyridyl ligand contains two pyridine groups (C5H4N).

| Anionic Ligand | Name |

|---|---|

| F− | fluoro |

| Cl− | chloro |

| Br− | bromo |

| I− | iodo |

| CN− | cyano |

| \(\ce{NO3-}\) | nitrato |

| OH− | hydroxo |

| O2– | oxo |

| \(\ce{C2O4^2-}\) | oxalato |

| \(\ce{CO2^2-}\) | carbonato |

When the complex is either a cation or a neutral molecule, the name of the central metal atom is spelled exactly like the name of the element and is followed by a Roman numeral in parentheses to indicate its oxidation state (Tables \(\PageIndex{2}\), \(\PageIndex{3}\), and \(\PageIndex{3}\)). When the complex is an anion, the suffix -ate is added to the stem of the name of the metal, followed by the Roman numeral designation of its oxidation state.

| Examples in Which the Complex Is Cation | |

| [Co(NH3)6]Cl3 | hexaaminecobalt(III) chloride |

| [Pt(NH3)4Cl2]2+ | tetraaminedichloroplatinum(IV) ion |

| [Ag(NH3)2]+ | diaminesilver(I) ion |

| [Cr(H2O)4Cl2]Cl | tetraaquadichlorochromium(III) chloride |

| [Co(H2NCH2CH2NH2)3]2(SO4)3 | tris(ethylenediamine)cobalt(III) sulfate |

| Examples in Which the Complex Is Neutral | |

| [Pt(NH3)2Cl4] | diaminetetrachloroplatinum(IV) |

| [Ni(H2NCH2CH2NH2)2Cl2] | dichlorobis(ethylenediamine)nickel(II) |

| Examples in Which the Complex Is an Anion | |

| [PtCl6]2− | hexachloroplatinate(IV) ion |

| Na2[S nCl6] | sodium hexachlorostannate(IV) |

Sometimes, the Latin name of the metal is used when the English name is clumsy. For example, ferrate is used instead of ironate, plumbate instead leadate, and stannate instead of tinate. The oxidation state of the metal is determined based on the charges of each ligand and the overall charge of the coordination compound. For example, in [Cr(H2O)4Cl2]Br, the coordination sphere (in brackets) has a charge of 1+ to balance the bromide ion. The water ligands are neutral, and the chloride ligands are anionic with a charge of 1− each. To determine the oxidation state of the metal, we set the overall charge equal to the sum of the ligands and the metal: +1 = −2 + x, so the oxidation state (x) is equal to 3+.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Coordination Numbers and Oxidation States

Determine the name of the following complexes and give the coordination number of the central metal atom.

- Na2[PtCl6]

- K3[Fe(C2O4)3]

- [Co(NH3)5Cl]Cl2

Solution

- There are two Na+ ions, so the coordination sphere has a negative two charge: [PtCl6]2−. There are six anionic chloride ligands, so −2 = −6 + x, and the oxidation state of the platinum is 4+. The name of the complex is sodium hexachloroplatinate(IV), and the coordination number is six.

- The coordination sphere has a charge of 3− (based on the potassium) and the oxalate ligands each have a charge of 2−, so the metal oxidation state is given by −3 = −6 + x, and this is an iron(III) complex. The name is potassium trisoxalatoferrate(III) (note that tris is used instead of tri because the ligand name starts with a vowel). Because oxalate is a bidentate ligand, this complex has a coordination number of six.

- In this example, the coordination sphere has a cationic charge of 2+. The NH3 ligand is neutral, but the chloro ligand has a charge of 1−. The oxidation state is found by +2 = −1 + x and is 3+, so the complex is pentaaminechlorocobalt(III) chloride and the coordination number is six.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

The complex potassium dicyanoargenate(I) is used to make antiseptic compounds. Give the formula and coordination number.

- Answer

-

K[Ag(CN)2]; coordination number two

The Structures of Complexes

The most common structures of the complexes in coordination compounds are octahedral, tetrahedral, and square planar (Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)). For transition metal complexes, the coordination number determines the geometry around the central metal ion. Table \(\PageIndex{3}\) compares coordination numbers to the molecular geometry:

| Coordination Number | Molecular Geometry | Example |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | linear | [Ag(NH3)2]+ |

| 3 | trigonal planar | [Cu(CN)3]2− |

| 4 | tetrahedral(d0 or d10), low oxidation states for M | [Ni(CO)4] |

| 4 | square planar (d8) | [NiCl4]2− |

| 5 | trigonal bipyramidal | [CoCl5]2− |

| 5 | square pyramidal | [VO(CN)4]2− |

| 6 | octahedral | [CoCl6]3− |

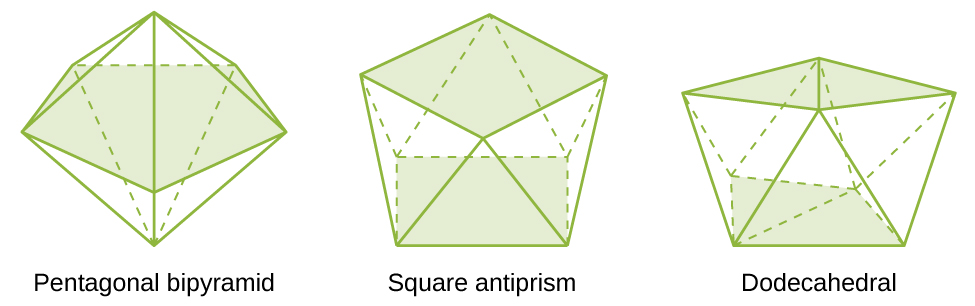

| 7 | pentagonal bipyramid | [ZrF7]3− |

| 8 | square antiprism | [ReF8]2− |

| 8 | dodecahedron | [Mo(CN)8]4− |

| 9 and above | more complicated structures | [ReH9]2− |

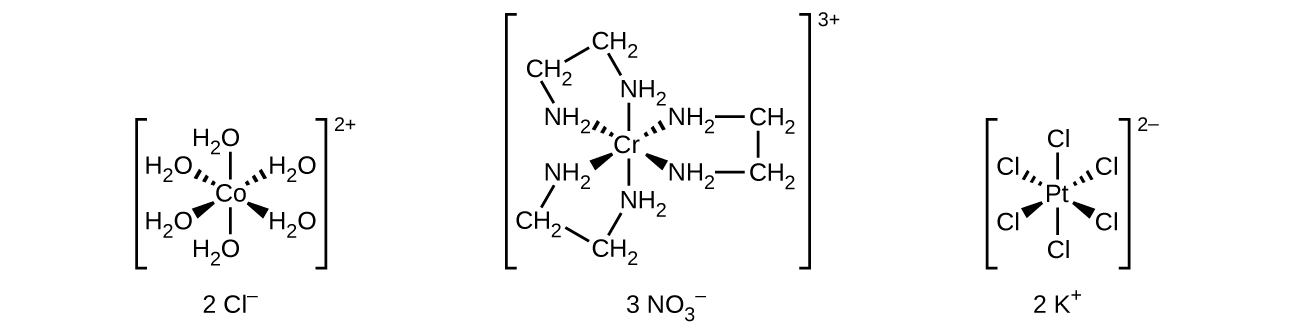

Unlike main group atoms in which both the bonding and nonbonding electrons determine the molecular shape, the nonbonding d-electrons do not change the arrangement of the ligands. Octahedral complexes have a coordination number of six, and the six donor atoms are arranged at the corners of an octahedron around the central metal ion. Examples are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\). The chloride and nitrate anions in [Co(H2O)6]Cl2 and [Cr(en)3](NO3)3, and the potassium cations in K2[PtCl6], are outside the brackets and are not bonded to the metal ion.

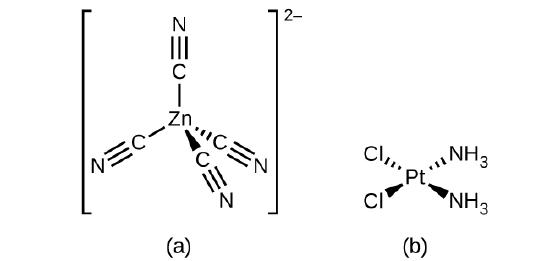

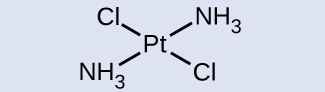

For transition metals with a coordination number of four, two different geometries are possible: tetrahedral or square planar. Unlike main group elements, where these geometries can be predicted from VSEPR theory, a more detailed discussion of transition metal orbitals (discussed in the section on Crystal Field Theory) is required to predict which complexes will be tetrahedral and which will be square planar. In tetrahedral complexes such as [Zn(CN)4]2− (Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)), each of the ligand pairs forms an angle of 109.5°. In square planar complexes, such as [Pt(NH3)2Cl2], each ligand has two other ligands at 90° angles (called the cis positions) and one additional ligand at an 180° angle, in the trans position.

Isomerism in Complexes

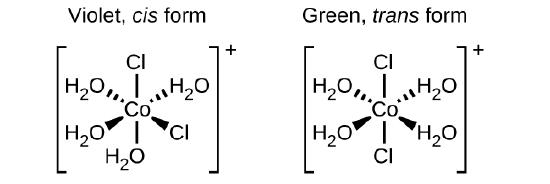

Isomers are different chemical species that have the same chemical formula. Transition metals often form geometric isomers, in which the same atoms are connected through the same types of bonds but with differences in their orientation in space. Coordination complexes with two different ligands in the cis and trans positions from a ligand of interest form isomers. For example, the octahedral [Co(NH3)4Cl2]+ ion has two isomers. In the cis configuration, the two chloride ligands are adjacent to each other (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). The other isomer, the trans configuration, has the two chloride ligands directly across from one another.

Different geometric isomers of a substance are different chemical compounds. They exhibit different properties, even though they have the same formula. For example, the two isomers of [Co(NH3)4Cl2]NO3 differ in color; the cis form is violet, and the trans form is green. Furthermore, these isomers have different dipole moments, solubilities, and reactivities. As an example of how the arrangement in space can influence the molecular properties, consider the polarity of the two [Co(NH3)4Cl2]NO3 isomers. Remember that the polarity of a molecule or ion is determined by the bond dipoles (which are due to the difference in electronegativity of the bonding atoms) and their arrangement in space. In one isomer, cis chloride ligands cause more electron density on one side of the molecule than on the other, making it polar. For the trans isomer, each ligand is directly across from an identical ligand, so the bond dipoles cancel out, and the molecule is nonpolar.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\): Geometric Isomers

Identify which geometric isomer of [Pt(NH3)2Cl2] is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)b. Draw the other geometric isomer and give its full name.

Solution

In the Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)b, the two chlorine ligands occupy cis positions. The other form is shown in below. When naming specific isomers, the descriptor is listed in front of the name. Therefore, this complex is trans-diaminedichloroplatinum(II).

The trans isomer of [Pt(NH3)2Cl2] has each ligand directly across from an adjacent ligand.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

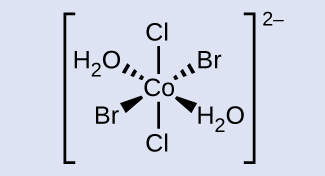

Draw the ion trans-diaqua-trans-dibromo-trans-dichlorocobalt(II).

- Answer

-

Cobalt is located at the center with the left and right wedges connected to bromine and H 2 O respectively. The left and right dash lines are connected to H 2 O and bromine respectively. Pointing directly upwards and downwards opposite from one another are the chlorine. The entire structural formula is enclosed in square bracket with a superscript of 2 negative.

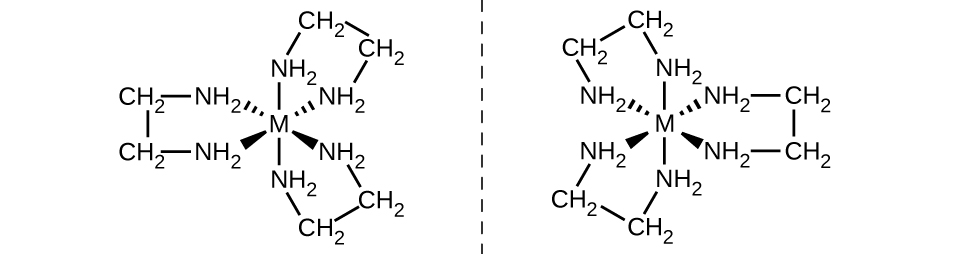

Another important type of isomers are optical isomers, or enantiomers, in which two objects are exact mirror images of each other but cannot be lined up so that all parts match. This means that optical isomers are nonsuperimposable mirror images. A classic example of this is a pair of hands, in which the right and left hand are mirror images of one another but cannot be superimposed. Optical isomers are very important in organic and biochemistry because living systems often incorporate one specific optical isomer and not the other. Unlike geometric isomers, pairs of optical isomers have identical properties (boiling point, polarity, solubility, etc.). Optical isomers differ only in the way they affect polarized light and how they react with other optical isomers. For coordination complexes, many coordination compounds such as [M(en)3]n+ [in which Mn+ is a central metal ion such as iron(III) or cobalt(II)] form enantiomers, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\). These two isomers will react differently with other optical isomers. For example, DNA helices are optical isomers, and the form that occurs in nature (right-handed DNA) will bind to only one isomer of [M(en)3]n+ and not the other.

The [Co(en)2Cl2]+ ion exhibits geometric isomerism (cis/trans), and its cis isomer exists as a pair of optical isomers (Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\)).

Linkage isomers occur when the coordination compound contains a ligand that can bind to the transition metal center through two different atoms. For example, the CN ligand can bind through the carbon atom (cyano) or through the nitrogen atom (isocyano). Similarly, SCN− can be bound through the sulfur or nitrogen atom, affording two distinct compounds ([Co(NH3)5SCN]2+ or [Co(NH3)5NCS]2+).

Ionization isomers (or coordination isomers) occur when one anionic ligand in the inner coordination sphere is replaced with the counter ion from the outer coordination sphere. A simple example of two ionization isomers are [CoCl6][Br] and [CoCl5Br][Cl].

Coordination Complexes in Nature and Technology

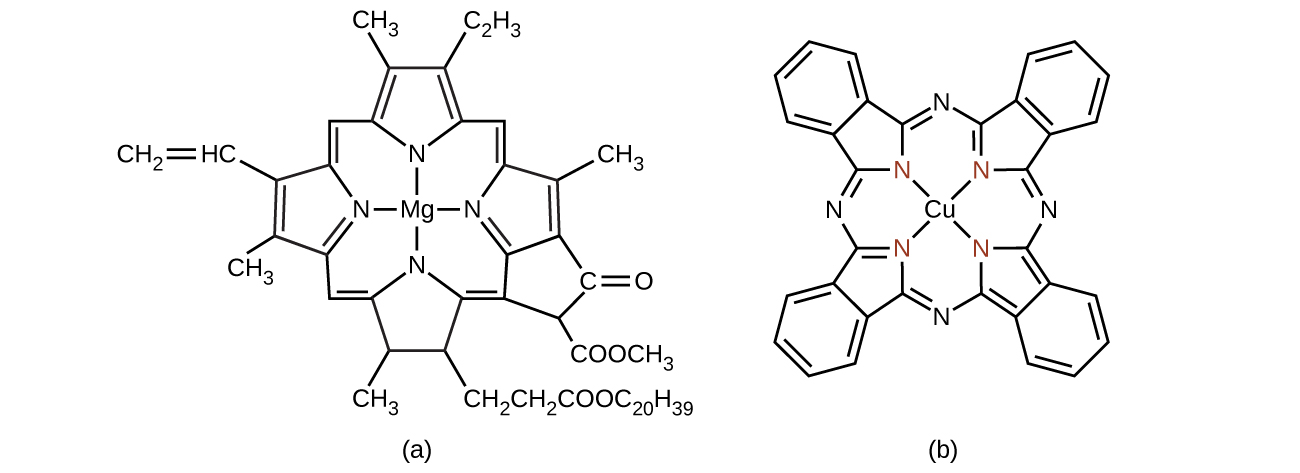

Chlorophyll, the green pigment in plants, is a complex that contains magnesium (Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\)). This is an example of a main group element in a coordination complex. Plants appear green because chlorophyll absorbs red and purple light; the reflected light consequently appears green. The energy resulting from the absorption of light is used in photosynthesis.

Transition Metal Catalysts

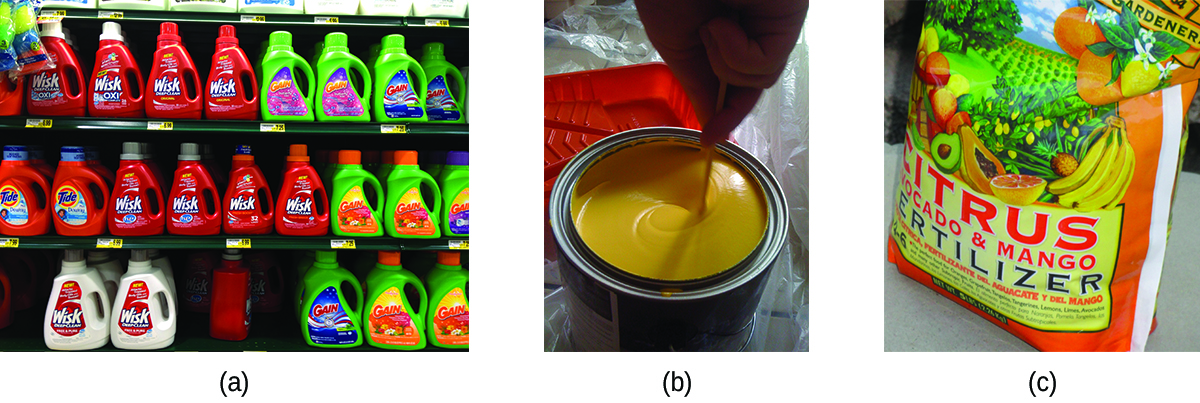

One of the most important applications of transition metals is as industrial catalysts. As you recall from the chapter on kinetics, a catalyst increases the rate of reaction by lowering the activation energy and is regenerated in the catalytic cycle. Over 90% of all manufactured products are made with the aid of one or more catalysts. The ability to bind ligands and change oxidation states makes transition metal catalysts well suited for catalytic applications. Vanadium oxide is used to produce 230,000,000 tons of sulfuric acid worldwide each year, which in turn is used to make everything from fertilizers to cans for food. Plastics are made with the aid of transition metal catalysts, along with detergents, fertilizers, paints, and more (Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\)). Very complicated pharmaceuticals are manufactured with catalysts that are selective, reacting with one specific bond out of a large number of possibilities. Catalysts allow processes to be more economical and more environmentally friendly. Developing new catalysts and better understanding of existing systems are important areas of current research.

Many other coordination complexes are also brightly colored. The square planar copper(II) complex phthalocyanine blue (from Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\)) is one of many complexes used as pigments or dyes. This complex is used in blue ink, blue jeans, and certain blue paints.

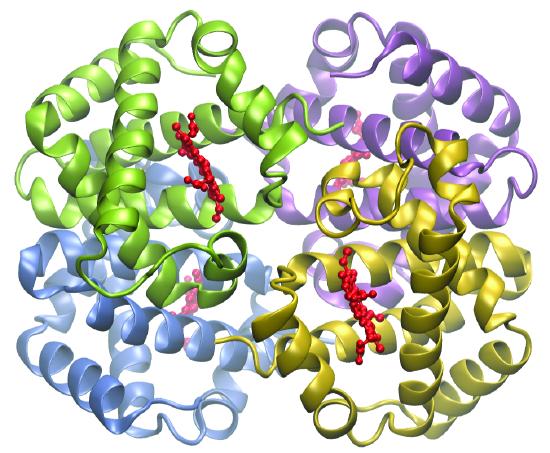

The structure of heme (Figure \(\PageIndex{15}\)), the iron-containing complex in hemoglobin, is very similar to that in chlorophyll. In hemoglobin, the red heme complex is bonded to a large protein molecule (globin) by the attachment of the protein to the heme ligand. Oxygen molecules are transported by hemoglobin in the blood by being bound to the iron center. When the hemoglobin loses its oxygen, the color changes to a bluish red. Hemoglobin will only transport oxygen if the iron is Fe2+; oxidation of the iron to Fe3+ prevents oxygen transport.

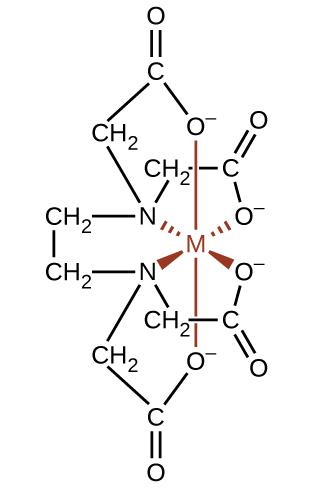

Complexing agents often are used for water softening because they tie up such ions as Ca2+, Mg2+, and Fe2+, which make water hard. Many metal ions are also undesirable in food products because these ions can catalyze reactions that change the color of food. Coordination complexes are useful as preservatives. For example, the ligand EDTA, (HO2CCH2)2NCH2CH2N(CH2CO2H)2, coordinates to metal ions through six donor atoms and prevents the metals from reacting (Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\)). This ligand also is used to sequester metal ions in paper production, textiles, and detergents, and has pharmaceutical uses.

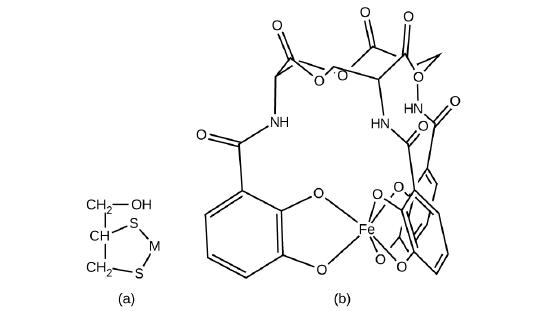

Complexing agents that tie up metal ions are also used as drugs. British Anti-Lewisite (BAL), HSCH2CH(SH)CH2OH, is a drug developed during World War I as an antidote for the arsenic-based war gas Lewisite. BAL is now used to treat poisoning by heavy metals, such as arsenic, mercury, thallium, and chromium. The drug is a ligand and functions by making a water-soluble chelate of the metal; the kidneys eliminate this metal chelate (Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\)). Another polydentate ligand, enterobactin, which is isolated from certain bacteria, is used to form complexes of iron and thereby to control the severe iron buildup found in patients suffering from blood diseases such as Cooley’s anemia, who require frequent transfusions. As the transfused blood breaks down, the usual metabolic processes that remove iron are overloaded, and excess iron can build up to fatal levels. Enterobactin forms a water-soluble complex with excess iron, and the body can safely eliminate this complex.

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\): Chelation Therapy

Ligands like BAL and enterobactin are important in medical treatments for heavy metal poisoning. However, chelation therapies can disrupt the normal concentration of ions in the body, leading to serious side effects, so researchers are searching for new chelation drugs. One drug that has been developed is dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA), shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{18}\). Identify which atoms in this molecule could act as donor atoms.

Solution

All of the oxygen and sulfur atoms have lone pairs of electrons that can be used to coordinate to a metal center, so there are six possible donor atoms. Geometrically, only two of these atoms can be coordinated to a metal at once. The most common binding mode involves the coordination of one sulfur atom and one oxygen atom, forming a five-member ring with the metal.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Some alternative medicine practitioners recommend chelation treatments for ailments that are not clearly related to heavy metals, such as cancer and autism, although the practice is discouraged by many scientific organizations.1 Identify at least two biologically important metals that could be disrupted by chelation therapy.

- Answer

-

Ca, Fe, Zn, and Cu

Ligands are also used in the electroplating industry. When metal ions are reduced to produce thin metal coatings, metals can clump together to form clusters and nanoparticles. When metal coordination complexes are used, the ligands keep the metal atoms isolated from each other. It has been found that many metals plate out as a smoother, more uniform, better-looking, and more adherent surface when plated from a bath containing the metal as a complex ion. Thus, complexes such as [Ag(CN)2]− and [Au(CN)2]− are used extensively in the electroplating industry.

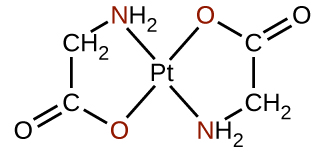

In 1965, scientists at Michigan State University discovered that there was a platinum complex that inhibited cell division in certain microorganisms. Later work showed that the complex was cis-diaminedichloroplatinum(II), [Pt(NH3)2(Cl)2], and that the trans isomer was not effective. The inhibition of cell division indicated that this square planar compound could be an anticancer agent. In 1978, the US Food and Drug Administration approved this compound, known as cisplatin, for use in the treatment of certain forms of cancer. Since that time, many similar platinum compounds have been developed for the treatment of cancer. In all cases, these are the cis isomers and never the trans isomers. The diamine (NH3)2 portion is retained with other groups, replacing the dichloro [(Cl)2] portion. The newer drugs include carboplatin, oxaliplatin, and satraplatin.

Summary

The transition elements and main group elements can form coordination compounds, or complexes, in which a central metal atom or ion is bonded to one or more ligands by coordinate covalent bonds. Ligands with more than one donor atom are called polydentate ligands and form chelates. The common geometries found in complexes are tetrahedral and square planar (both with a coordination number of four) and octahedral (with a coordination number of six). Cis and trans configurations are possible in some octahedral and square planar complexes. In addition to these geometrical isomers, optical isomers (molecules or ions that are mirror images but not superimposable) are possible in certain octahedral complexes. Coordination complexes have a wide variety of uses including oxygen transport in blood, water purification, and pharmaceutical use.

Footnotes

- National Council against Health Fraud, NCAHF Policy Statement on Chelation Therapy, (Peabody, MA, 2002).

Glossary

- bidentate ligand

- ligand that coordinates to one central metal through coordinate bonds from two different atoms

- central metal

- ion or atom to which one or more ligands is attached through coordinate covalent bonds

- chelate

- complex formed from a polydentate ligand attached to a central metal

- chelating ligand

- ligand that attaches to a central metal ion by bonds from two or more donor atoms

- cis configuration

- configuration of a geometrical isomer in which two similar groups are on the same side of an imaginary reference line on the molecule

- coordination compound

- substance consisting of atoms, molecules, or ions attached to a central atom through Lewis acid-base interactions

- coordination number

- number of coordinate covalent bonds to the central metal atom in a complex or the number of closest contacts to an atom in a crystalline form

- coordination sphere

- central metal atom or ion plus the attached ligands of a complex

- donor atom

- atom in a ligand with a lone pair of electrons that forms a coordinate covalent bond to a central metal

- ionization isomer

- (or coordination isomer) isomer in which an anionic ligand is replaced by the counter ion in the inner coordination sphere

- ligand

- ion or neutral molecule attached to the central metal ion in a coordination compound

- linkage isomer

- coordination compound that possesses a ligand that can bind to the transition metal in two different ways (CN− vs. NC−)

- monodentate

- ligand that attaches to a central metal through just one coordinate covalent bond

- optical isomer

- (also, enantiomer) molecule that is a nonsuperimposable mirror image with identical chemical and physical properties, except when it reacts with other optical isomers

- polydentate ligand

- ligand that is attached to a central metal ion by bonds from two or more donor atoms, named with prefixes specifying how many donors are present (e.g., hexadentate = six coordinate bonds formed)

- trans configuration

- configuration of a geometrical isomer in which two similar groups are on opposite sides of an imaginary reference line on the molecule