16.2: Water and the pH Scale

- Page ID

- 60741

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction

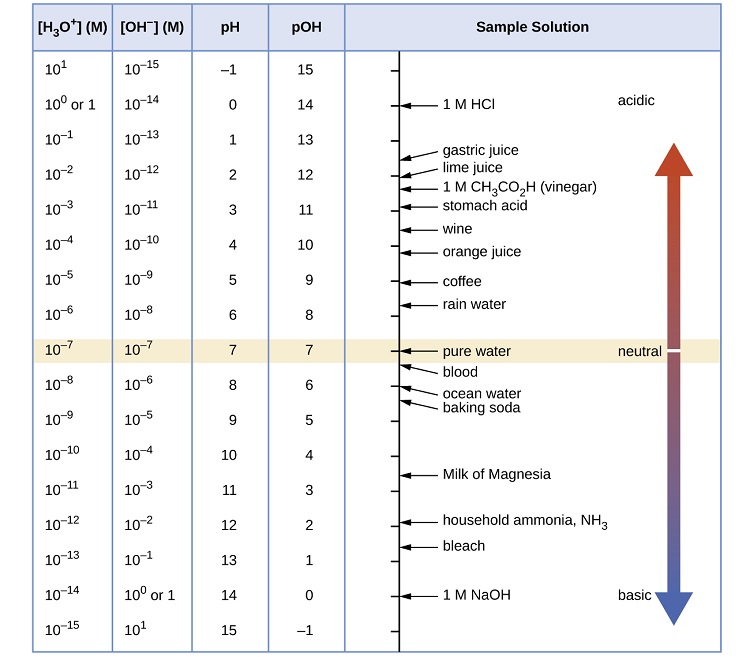

We have all heard of the pH scale, neutral water has a pH =7, acid is lower and bases are higher. We may also know the pH of some common substances as shown in figure 16.2.1.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) Table relating ph to concentrations for various substances.

Most chemistry students know the mathematical equation pH=-log[H+], but what does it mean? For starts, pH is a way to measure the concentration of substances that are very dilute, and in this section we shall seek to develop an understanding of pH

Autoionization Constant (Kw)

\[H_2O(l) +H_2O(l) \rightleftharpoons H_3O^+(aq) + OH^-(aq)\]

\[K=\frac{[H_{3}O^{+}][OH^{-}]}{[H_{2}O]^{2}}\]

Note, in the equilibrium chapter we were told to ignore pure solid and liquid substances in heterogeneous equilibria because their density is constant, and thus their concentration is constant, but this is not a heterogeneous mixture, but a homogenous solution. The K for the above value is a very small number and so the number of water molecules that dissociates is so small that it is negligible compared to the initial water constant, and thus the water concentration can be considered constant. Thus the water concentration is integrated into the Ionization constant and Kw is defined as:

\[\large{K_w=[H_3O^+][OH^-]=1.0 \times 10^{−14}}\]

For neutral water

\[[H_3O^+]=[OH^-]\]

substituting

\[K_\ce{w}=\ce{[H_3O^+][OH^- ]}=\ce{[H_3O^+]^2}=\ce{[OH^- ]^2}=1.0 \times 10^{−14}\]

Taking the square root of both sides gives

\[[H_3O^+]=[OH^-]=1x10^{-7}\]

Note, for pure water the concentration is \[\text{Concentration of pure water}=\left (\frac{1000g}{l} \right )\left ( \frac{mol}{18.015g} \right )=55.56\frac{mol}{l}\]

So the fraction dissociated is

\[\frac{[H_3O^+]}{[H_2O]}= \frac{1x10^{-7}}{55.56}=1.8x10^{-9}\]

(or taking the reciprocal, means that for every 556,000,000 molecules of water, one forms a hydronium ion. This allows us to say that the concentration of the water is constant. Also, note from the introduction, that this is a dynamic not static system, we are not saying that some molecules are always hydronium or hydroxide, but that molecules are rapidly interacting and a specific oxygen atom may at a given time have one, two or three protons associated with it, although the vast majority is 2, to the point that the concentration of hydronium or hydroxide in a liter is 10-7moles.

pH, pOH and pKw

Noting \[[H_3O^+][OH^-]=K_w=10^{-14}\]

we can take the log of both sides and multiply by minus 1, this gives us

\[\large{pH + pOH=14}\]

So if you know either hydronium or hydroxide, you know the other.

pH & Significant Figures

Note, pX is the log of how many times you divide by 10 (while log is how many times you multiply by 10). That is, it is an operation, not a number.

Figure\(\PageIndex{2}\): Showing significant figures for logarithms

Why do we need to define things this way?

What is the pH of 0.1M HCl and 0.1M NaOH? (Noting that they both have one sig fig for the concentration).

For 0.1M HCL, pH= -log(0.1)=1, so the [HCl]=.1 and its pH = 1

For 0.1M NaOH], pOH=-log(0.1)=1, which means the pH=13, (remember pH+pOH=14), but 13 has two sig. figures, so you must use the convention in figure 16.2.2, and the answers are pH=1.0 for 1MHCL, and pH=13.0 for 1M NaOH.

(Realize that pH=13 equates to the decimal 0.0000000000001 or \(\frac{1}{10^{13}}\), that is, it is not a measured number, but the number of times you divided by 10.

Measuring pH

There are two basic ways to measure pH

1. With an Indicator

Indicators are chemicals that change color at specific pHs. The basic idea is that an indicator is an acid or a base that has a different color in the protonated or unprotonated state, and changes that state at a defined pH.

Figure shows an acidic indicator where the acid has a different color than its conjugated base. At low pH there are lots of hydronium and so it stays protonated. As the pH raises the hydronium ion concentration goes down and the hydroxide goes up, pulling the protons from the indicator.

Figure Phenolphthalein is a common indicator which is clear below a pH of around 9, and becomes pink after that.

2. With a pH Meter

A pH probe is an electronic device that measures the pH. These are very common and they should always be checked against standard solutions of known pH and calibrated if they read incorrectly. The workings of pH probes will be covered in analytical chemistry, but the following 2:30 min Youtube from Oxford Press does a good job in explaining how the pH probe works.

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\) 2:30 YouTuve describing the operation of a pH probe developed by Oxford University Press (https://youtu.be/aIn4D2QXUy4).

Robert E. Belford (University of Arkansas Little Rock; Department of Chemistry). The breadth, depth and veracity of this work is the responsibility of Robert E. Belford, rebelford@ualr.edu. You should contact him if you have any concerns. This material has both original contributions, and content built upon prior contributions of the LibreTexts Community and other resources, including but not limited to: