11.6: Metallic Bonding

- Page ID

- 478313

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Explain why metallic bonding occurs.

- Describe the properties of metals.

- Explain what an alloy is composed of.

Why do metals behave the way they do?

The image below is of a copper plate that was made in 1893. The utensil has a great deal of elaborate decoration, and the item is very useful. What would have happened if this plate was made of copper (I) chloride instead? Copper (I) chloride does contain copper, after all. However, the \(\ce{CuCl}\) would end up as a powder when a metalworker pounded on it to shape it. Metals behave in unique ways. The bonding that occurs in a metal is responsible for its distinctive properties: luster, malleability, ductility, and excellent conductivity.

The Metallic Bond

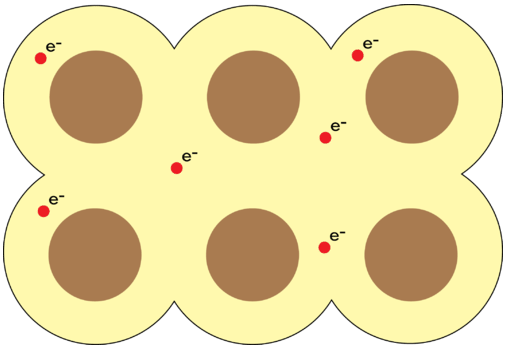

Pure metals are crystalline solids, but unlike ionic compounds, every point in the crystal lattice is occupied by an identical atom. The electrons in the outer energy levels of a metal are mobile and capable of drifting from one metal atom to another. This means that the metal is more properly viewed as an array of positive ions surrounded by a sea of mobile valence electrons. Electrons which are capable of moving freely throughout the empty orbitals of the metallic crystal are called delocalized electrons (see below). A metallic bond is the attraction of the stationary metal cations to the surrounding mobile electrons.

Properties of Metals

The metallic bonding model explains the physical properties of metals. Metals conduct electricity and heat very well because of their free-flowing electrons. As electrons enter one end of a piece of metal, an equal number of electrons flow outward from the other end. When light is shone onto the surface of a metal, its electrons absorb small amounts of energy and become excited into one of its many empty orbitals. The electrons immediately fall back down to lower energy levels and emit light. This process is responsible for the high luster of metals. Recall that ionic compounds are very brittle. Application of a force results in like-charged ions in the crystal coming too close to one another, causing the crystal to shatter. When a force is applied to a metal, the free-flowing electrons can slip in between the stationary cations and prevent them from coming in contact. Imagine ball bearings that have been coated with oil sliding past one another. As a result, metals are very malleable and ductile. They can be hammered into shapes, rolled into thin sheets, or pulled into thin wires.

Alloys

An alloy is a mixture composed of two or more elements, at least one of which is a metal. You are probably familiar with some alloys such as brass and bronze. Brass is an alloy of copper and zinc. Bronze is an alloy of copper and tin. Alloys are commonly used in manufactured items because the properties of these metal mixtures are often superior to a pure metal. Bronze is harder than copper and more easily cast. Brass is very malleable and its acoustic properties make it useful for musical instruments.

Steels are a very important class of alloys. The many types of steels are primarily composed of iron, with various amounts of the elements carbon, chromium, manganese, nickel, molybdenum, and boron. Steels are widely used in building construction because of their strength, hardness, and resistance to corrosion. Most large modern structures like skyscrapers and stadiums are supported by a steel skeleton.

Section Summary

- The metallic bond is responsible for the properties of metals.

- Metals conduct electricity and heat well.

- Metals are ductile and malleable.

- Metals have luster.

- Alloys are mixtures of materials, at least one of which is a metal.

Glossary

- malleable

- substance that is easily shaped.

- luster

- property of having a shiny surface.

- delocalized electrons

- electrons which are capable of moving freely throughout the empty orbitals of a chemically bonded substance.

- metallic bond

- attraction of the stationary metal cations to the surrounding mobile electrons.

- alloy

- a mixture composed of two or more elements, at least one of which is a metal.