19.4: Spectroscopic and Magnetic Properties of Coordination Compounds

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 452892

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Outline the basic premise of crystal field theory (CFT)

- Identify molecular geometries associated with various d-orbital splitting patterns

- Predict electron configurations of split d orbitals for selected transition metal atoms or ions

- Explain spectral and magnetic properties in terms of CFT concepts

The behavior of coordination compounds cannot be adequately explained by the same theories used for main group element chemistry. The observed geometries of coordination complexes are not consistent with hybridized orbitals on the central metal overlapping with ligand orbitals, as would be predicted by valence bond theory. The observed colors indicate that the d orbitals often occur at different energy levels rather than all being degenerate, that is, of equal energy, as are the three p orbitals. To explain the stabilities, structures, colors, and magnetic properties of transition metal complexes, a different bonding model has been developed. Just as valence bond theory explains many aspects of bonding in main group chemistry, crystal field theory is useful in understanding and predicting the behavior of transition metal complexes.

Crystal Field Theory

To explain the observed behavior of transition metal complexes (such as how colors arise), a model involving electrostatic interactions between the electrons from the ligands and the electrons in the unhybridized d orbitals of the central metal atom has been developed. This electrostatic model is crystal field theory (CFT). It allows us to understand, interpret, and predict the colors, magnetic behavior, and some structures of coordination compounds of transition metals.

CFT focuses on the nonbonding electrons on the central metal ion in coordination complexes not on the metal-ligand bonds. Like valence bond theory, CFT tells only part of the story of the behavior of complexes. However, it tells the part that valence bond theory does not. In its pure form, CFT ignores any covalent bonding between ligands and metal ions. Both the ligand and the metal are treated as infinitesimally small point charges.

All electrons are negative, so the electrons donated from the ligands will repel the electrons of the central metal. Let us consider the behavior of the electrons in the unhybridized d orbitals in an octahedral complex. The five d orbitals consist of lobe-shaped regions and are arranged in space, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\). In an octahedral complex, the six ligands coordinate along the axes.

In an uncomplexed metal ion in the gas phase, the electrons are distributed among the five d orbitals in accord with Hund's rule because the orbitals all have the same energy. However, when ligands coordinate to a metal ion, the energies of the d orbitals are no longer the same.

In octahedral complexes, the lobes in two of the five d orbitals, the \(d_{z^2}\) and \(d_{x^2−y^2}\) orbitals, point toward the ligands (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). These two orbitals are called the \(e_g\) orbitals (the symbol actually refers to the symmetry of the orbitals, but we will use it as a convenient name for these two orbitals in an octahedral complex). The other three orbitals, the \(d_{xy}\), \(d_{xz}\), and \(d_{yz}\) orbitals, have lobes that point between the ligands and are called the \(t_{2g}\) orbitals (again, the symbol really refers to the symmetry of the orbitals). As six ligands approach the metal ion along the axes of the octahedron, their point charges repel the electrons in the d orbitals of the metal ion. However, the repulsions between the electrons in the eg orbitals (the \(d_{z^2}\) and \(d_{x^2−y^2}\) orbitals) and the ligands are greater than the repulsions between the electrons in the \(t_{2g}\) orbitals (the \(d_{zy}\), \(d_{xz}\), and \(d_{yz}\) orbitals) and the ligands. This is because the lobes of the eg orbitals point directly at the ligands, whereas the lobes of the \(t_{2g}\) orbitals point between them. Thus, electrons in the eg orbitals of the metal ion in an octahedral complex have higher potential energies than those of electrons in the \(t_{2g}\) orbitals. The difference in energy may be represented as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\).

The difference in energy between the eg and the t2g orbitals is called the crystal field splitting and is symbolized by \(Δ_{oct}\), where oct stands for octahedral.

The magnitude of Δoct depends on many factors, including the nature of the six ligands located around the central metal ion, the charge on the metal, and whether the metal is using 3d, 4d, or 5d orbitals. Different ligands produce different crystal field splittings. The increasing crystal field splitting produced by ligands is expressed in the spectrochemical series, a short version of which is given here:

\[\Large \xrightarrow[\text{a few ligands of the spectrochemical series, in order of increasing field strength of the ligand}]{\ce{I^{-}< Br^{-}< Cl^{-}< F^{-} < H_2O < NH_3 < en < NO_2^{-} < CN^{-}}} \nonumber \]

In this series, ligands on the left cause small crystal field splittings and are weak-field ligands, whereas those on the right cause larger splittings and are strong-field ligands. Thus, the Δoct value for an octahedral complex with iodide ligands (I−) is much smaller than the Δoct value for the same metal with cyanide ligands (CN−).

Electrons in the d orbitals follow the aufbau (“filling up”) principle, which says that the orbitals will be filled to give the lowest total energy, just as in main group chemistry. When two electrons occupy the same orbital, the like charges repel each other. The energy needed to pair up two electrons in a single orbital is called the pairing energy (P). Electrons will always singly occupy each orbital in a degenerate set before pairing. P is similar in magnitude to Δoct. When electrons fill the d orbitals, the relative magnitudes of Δoct and P determine which orbitals will be occupied.

In [Fe(CN)6]4−, the strong field of six cyanide ligands produces a large Δoct. Under these conditions, the electrons require less energy to pair than they require to be excited to the eg orbitals (Δoct > P). The six 3d electrons of the Fe2+ ion pair in the three t2g orbitals (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). Complexes in which the electrons are paired because of the large crystal field splitting are called low-spin complexes because the number of unpaired electrons (spins) is minimized.

In [Fe(H2O)6]2+, on the other hand, the weak field of the water molecules produces only a small crystal field splitting (Δoct < P). Because it requires less energy for the electrons to occupy the eg orbitals than to pair together, there will be an electron in each of the five 3d orbitals before pairing occurs. For the six d electrons on the iron(II) center in [Fe(H2O)6]2+, there will be one pair of electrons and four unpaired electrons (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). Complexes such as the [Fe(H2O)6]2+ ion, in which the electrons are unpaired because the crystal field splitting is not large enough to cause them to pair, are called high-spin complexes because the number of unpaired electrons (spins) is maximized.

A similar line of reasoning shows why the [Fe(CN)6]3− ion is a low-spin complex with only one unpaired electron, whereas both the [Fe(H2O)6]3+ and [FeF6]3− ions are high-spin complexes with five unpaired electrons.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): High- and Low-Spin Complexes

Predict the number of unpaired electrons.

- \(\ce{K3[CrI6]}\)

- \(\ce{[Cu(en)2(H2O)2]Cl2}\)

- \(\ce{Na3[Co(NO2)6]}\)

Solution

The complexes are octahedral.

- Cr3+ has a d3 configuration. These electrons will all be unpaired.

- Cu2+ is d9, so there will be one unpaired electron.

- Co3+ has d6 valence electrons, so the crystal field splitting will determine how many are paired. Nitrite is a strong-field ligand, so the complex will be low spin. Six electrons will go in the t2g orbitals, leaving 0 unpaired.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

The size of the crystal field splitting only influences the arrangement of electrons when there is a choice between pairing electrons and filling the higher-energy orbitals. For which d-electron configurations will there be a difference between high- and low-spin configurations in octahedral complexes?

- Answer

-

d4, d5, d6, and d7

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\): CFT for Other Geometries

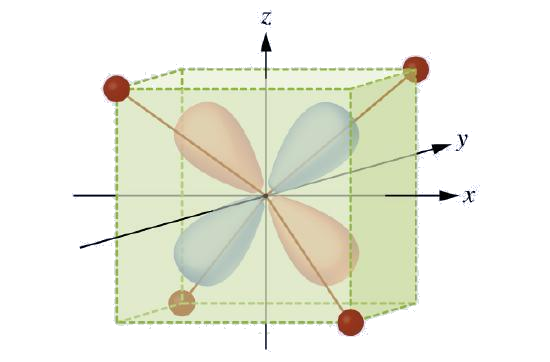

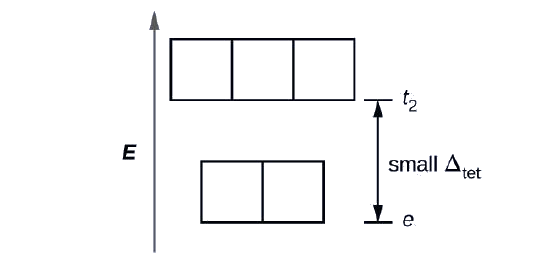

CFT is applicable to molecules in geometries other than octahedral. In octahedral complexes, remember that the lobes of the eg set point directly at the ligands. For tetrahedral complexes, the d orbitals remain in place, but now we have only four ligands located between the axes (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). None of the orbitals points directly at the tetrahedral ligands. However, the eg set (along the Cartesian axes) overlaps with the ligands less than does the t2g set. By analogy with the octahedral case, predict the energy diagram for the d orbitals in a tetrahedral crystal field. To avoid confusion, the octahedral eg set becomes a tetrahedral e set, and the octahedral t2g set becomes a t2 set.

Solution

Since CFT is based on electrostatic repulsion, the orbitals closer to the ligands will be destabilized and raised in energy relative to the other set of orbitals. The splitting is less than for octahedral complexes because the overlap is less, so \(Δ_{tet}\) is usually small \(\left(\Delta_{\text {tet}}=\frac{4}{9} \Delta_{oct}\right)\)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Explain how many unpaired electrons a tetrahedral d4 ion will have.

- Answer

-

4; because \(Δ_{tet}\) is small, all tetrahedral complexes are high spin and the electrons go into the t2 orbitals before pairing

The other common geometry is square planar. It is possible to consider a square planar geometry as an octahedral structure with a pair of trans ligands removed. The removed ligands are assumed to be on the z-axis. This changes the distribution of the d orbitals, as orbitals on or near the z-axis become more stable, and those on or near the x- or y-axes become less stable. This results in the octahedral t2g and the eg sets splitting and gives a more complicated pattern, as depicted below:

Magnetic Moments of Molecules and Ions

Experimental evidence of magnetic measurements supports the theory of high- and low-spin complexes. Remember that molecules such as O2 that contain unpaired electrons are paramagnetic. Paramagnetic substances are attracted to magnetic fields. Many transition metal complexes have unpaired electrons and hence are paramagnetic. Molecules such as N2 and ions such as Na+ and [Fe(CN)6]4− that contain no unpaired electrons are diamagnetic. Diamagnetic substances have a slight tendency to be repelled by magnetic fields.

When an electron in an atom or ion is unpaired, the magnetic moment due to its spin makes the entire atom or ion paramagnetic. The size of the magnetic moment of a system containing unpaired electrons is related directly to the number of such electrons: the greater the number of unpaired electrons, the larger the magnetic moment. Therefore, the observed magnetic moment is used to determine the number of unpaired electrons present. The measured magnetic moment of low-spin d6 [Fe(CN)6]4− confirms that iron is diamagnetic, whereas high-spin d6 [Fe(H2O)6]2+ has four unpaired electrons with a magnetic moment that confirms this arrangement.

Colors of Transition Metal Complexes

When atoms or molecules absorb light at the proper frequency, their electrons are excited to higher-energy orbitals. For many main group atoms and molecules, the absorbed photons are in the ultraviolet range of the electromagnetic spectrum, which cannot be detected by the human eye. For coordination compounds, the energy difference between the d orbitals often allows photons in the visible range to be absorbed.

The human eye perceives a mixture of all the colors, in the proportions present in sunlight, as white light. Complementary colors, those located across from each other on a color wheel, are also used in color vision. The eye perceives a mixture of two complementary colors, in the proper proportions, as white light. Likewise, when a color is missing from white light, the eye sees its complement. For example, when red photons are absorbed from white light, the eyes see the color green. When violet photons are removed from white light, the eyes see lemon yellow. The blue color of the [Cu(NH3)4]2+ ion results because this ion absorbs orange and red light, leaving the complementary colors of blue and green (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)).

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\): Colors of Complexes

The octahedral complex [Ti(H2O)6]3+ has a single d electron. To excite this electron from the ground state t2g orbital to the eg orbital, this complex absorbs light from 450 to 600 nm. The maximum absorbance corresponds to Δoct and occurs at 499 nm. Calculate the value of Δoct in Joules and predict what color the solution will appear.

Solution

Using Planck's equation (refer to the section on electromagnetic energy), we calculate:

\[\nu =\frac{c}{\lambda} \text { so } \frac{3.00 \times 10^8 m / s }{\frac{499 nm \times 1 m }{10^9 nm }}=6.01 \times 10^{14} Hz \nonumber \]

\[E=h \nu \text { so } 6.63 \times 10^{-34} J \cdot s \times 6.01 \times 10^{14} Hz =3.99 \times 10^{-19} \text { Joules/ion } \nonumber \]

Because the complex absorbs 600 nm (orange) through 450 (blue), the indigo, violet, and red wavelengths will be transmitted, and the complex will appear purple.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{3}\)

A complex that appears green, absorbs photons of what wavelengths?

- Answer

-

red, 620–800 nm

Small changes in the relative energies of the orbitals that electrons are transitioning between can lead to drastic shifts in the color of light absorbed. Therefore, the colors of coordination compounds depend on many factors. As shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\), different aqueous metal ions can have different colors. In addition, different oxidation states of one metal can produce different colors, as shown for the vanadium complexes in the link below.

The specific ligands coordinated to the metal center also influence the color of coordination complexes. For example, the iron(II) complex [Fe(H2O)6]SO4 appears blue-green because the high-spin complex absorbs photons in the red wavelengths (Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)). In contrast, the low-spin iron(II) complex K4[Fe(CN)6] appears pale yellow because it absorbs higher-energy violet photons.

Link to Learning

Watch this video of the reduction of vanadium complexes to observe the colorful effect of changing oxidation states.

In general, strong-field ligands cause a large split in the energies of d orbitals of the central metal atom (large Δoct). Transition metal coordination compounds with these ligands are yellow, orange, or red because they absorb higher-energy violet or blue light. On the other hand, coordination compounds of transition metals with weak-field ligands are often blue-green, blue, or indigo because they absorb lower-energy yellow, orange, or red light.

A coordination compound of the Cu+ ion has a d10 configuration, and all the eg orbitals are filled. To excite an electron to a higher level, such as the 4p orbital, photons of very high energy are necessary. This energy corresponds to very short wavelengths in the ultraviolet region of the spectrum. No visible light is absorbed, so the eye sees no change, and the compound appears white or colorless. A solution containing [Cu(CN)2]−, for example, is colorless. On the other hand, octahedral Cu2+ complexes have a vacancy in the eg orbitals, and electrons can be excited to this level. The wavelength (energy) of the light absorbed corresponds to the visible part of the spectrum, and Cu2+ complexes are almost always colored—blue, blue-green violet, or yellow (Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)). Although CFT successfully describes many properties of coordination complexes, molecular orbital explanations (beyond the introductory scope provided here) are required to understand fully the behavior of coordination complexes.