3.6: Colligative Properties of Solutions

- Page ID

- 221457

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objective

- Name the four colligative properties.

- Calculate changes in vapor pressure, melting point, and boiling point of solutions.

- Calculate the osmotic pressure of solutions.

The properties of solutions are very similar to the properties of their respective pure solvents. This makes sense because the majority of the solution is the solvent. However, some of the properties of solutions differ from pure solvents in measurable and predictable ways. The differences are proportional to the fraction that the solute particles occupy in the solution. These properties are called colligative properties; the word colligative comes from the Greek word meaning "related to the number," implying that these properties are related to the number of solute particles, not their identities.

Before we introduce the first colligative property, we need to introduce a new concentration unit. The mole fraction of the ith component in a solution, χi, is the number of moles of that component divided by the total number of moles in the sample:

\[\chi _{i}=\dfrac{moles\: of\: ith\, component}{total\: moles}\nonumber \]

(χ is the lowercase Greek letter chi.) The mole fraction is always a number between 0 and 1 (inclusive) and has no units; it is just a number.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Hydrocarbon Solution

A solution is made by mixing 12.0 g of C10H8 in 45.0 g of C6H6. What is the mole fraction of C10H8 in the solution?

Solution

We need to determine the number of moles of each substance, add them together to get the total number of moles, and then divide to determine the mole fraction of C10H8. The number of moles of C10H8 is as follows:

\[12.0g\: C_{10}H_{8}\times \frac{1mol\: C_{10}H_{8}}{128.10g\: C_{10}H_{8}}=0.0936\, mol\: C_{10}H_{8}\nonumber \]

The number of moles of C6H6 is as follows:

\[45.0g\: C_{6}H_{6}\times \frac{1mol\: C_{6}H_{6}}{78.12g\: C_{6}H_{6}}=0.576\, mol\: C_{6}H_{6}\nonumber \]

The total number of moles is

0.0936 mol + 0.576 mol = 0.670 mol

Now we can calculate the mole fraction of C10H8:

\[\chi _{C_{10}H_{8}}=\frac{0.0936mol}{0.670mol}=0.140\nonumber \]

The mole fraction is a number between 0 and 1 and is unit-less.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

A solution is made by mixing 33.8 g of CH3OH in 50.0 g of H2O. What is the mole fraction of CH3OH in the solution?

- Answer

-

0.275

A useful thing to note is that the sum of the mole fractions of all substances in a mixture equals 1. Thus the mole fraction of C6H6 in Example \(\PageIndex{1}\) could be calculated by evaluating the definition of mole fraction a second time, or—because there are only two substances in this particular mixture—we can subtract the mole fraction of the C10H8 from 1 to get the mole fraction of C6H6.

Vapor pressure depression

Now that this new concentration unit has been introduced, the first colligative property can be considered. As mentioned in Chapter 10, all pure liquids have a characteristic vapor pressure in equilibrium with the liquid phase, the partial pressure of which is dependent on temperature. Solutions, however, have a lower vapor pressure than the pure solvent has, and the amount of lowering is dependent on the fraction of solute particles, as long as the solute itself does not have a significant vapor pressure (the term nonvolatile is used to describe such solutes). This colligative property is called vapor pressure depression (or lowering). The actual vapor pressure of the solution can be calculated as follows:

\[P_{soln}=\chi _{solv}P_{solv}^{*}\nonumber \]

where Psoln is the vapor pressure of the solution, χsolv is the mole fraction of the solvent particles, and P*solv is the vapor pressure of the pure solvent at that temperature (which is data that must be provided). This equation is known as Raoult's law (the approximate pronunciation is rah-OOLT). Vapor pressure depression is rationalized by presuming that solute particles take positions at the surface in place of solvent particles, so not as many solvent particles can evaporate.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\): Vapor Pressure Reduction

A solution is made by mixing 12.0 g of C10H8 in 45.0 g of C6H6. If the vapor pressure of pure C6H6 is 95.3 torr, what is the vapor pressure of the solution?

Solution

This is the same solution that was in Example 15, but here we need the mole fraction of C6H6. The number of moles of C10H8 is as follows:

\[12.0g\: C_{10}H_{8}\times \frac{1mol\: C_{10}H_{8}}{128.10g\: C_{10}H_{8}}=0.0936\, mol\: C_{10}H_{8}\nonumber \]

The number of moles of C6H6 is as follows:

\[45.0g\: C_{6}H_{6}\times \frac{1mol\: C_{6}H_{6}}{78.12g\: C_{6}H_{6}}=0.576\, mol\: C_{6}H_{6}\nonumber \]

So the total number of moles is

0.0936 mol + 0.576 mol = 0.670 mol

Now we can calculate the mole fraction of C6H6:

\[\chi _{C_{10}H_{8}}=\frac{0.576mol}{0.670mol}=0.860\nonumber \]

(The mole fraction of C10H8 calculated in Example 15 plus the mole fraction of C6H6 equals 1, which is mathematically required by the definition of mole fraction.) Now we can use Raoult's law to determine the vapor pressure in equilibrium with the solution:

Psoln = (0.860)(95.3 torr) = 82.0 torr

The solution has a lower vapor pressure than the pure solvent.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

A solution is made by mixing 33.8 g of C6H12O6 in 50.0 g of H2O. If the vapor pressure of pure water is 25.7 torr, what is the vapor pressure of the solution?

- Answer

-

24.1 torr

Boiling point elevation

Two colligative properties are related to solution concentration as expressed in molality. As a review, recall the definition of molality:

\[molality-=\frac{moles\: solute}{kilograms\: solvent}\nonumber \]

Because the vapor pressure of a solution with a nonvolatile solute is depressed compared to that of the pure solvent, it requires a higher temperature for the solution's vapor pressure to reach 1.00 atm (760 torr). Recall that this is the definition of the normal boiling point: the temperature at which the vapor pressure of the liquid equals 1.00 atm. As such, the normal boiling point of the solution is higher than that of the pure solvent. This property is called boiling point elevation.

The change in boiling point (ΔTb) is easily calculated:

\[ΔT_b = mK_b\nonumber \]

where m is the molality of the solution and Kb is called the boiling point elevation constant, which is a characteristic of the solvent. Several boiling point elevation constants (as well as boiling point temperatures) are listed in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\).

| Liquid | Boiling Point (°C) | Kb (°C/m) |

|---|---|---|

| HC2H3O2 | 117.90 | 3.07 |

| C6H6 | 80.10 | 2.53 |

| CCl4 | 76.8 | 4.95 |

| H2O | 100.00 | 0.512 |

Remember that what is initially calculated is the change in boiling point temperature, not the new boiling point temperature. Once the change in boiling point temperature is calculated, it must be added to the boiling point of the pure solvent—because boiling points are always elevated—to get the boiling point of the solution.

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\)

What is the boiling point of a 2.50 m solution of C6H4Cl2 in CCl4? Assume that C6H4Cl2 is not volatile.

Solution

Using the equation for the boiling point elevation,

ΔTb = (2.50 m)(4.95°C/m) = 12.4°C

Note how the molality units have canceled. However, we are not finished. We have calculated the change in the boiling point temperature, not the final boiling point temperature. If the boiling point goes up by 12.4°C, we need to add this to the normal boiling point of CCl4 to get the new boiling point of the solution:

TBP = 76.8°C + 12.4°C = 89.2°C

The boiling point of the solution is predicted to be 89.2°C.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{3}\)

What is the boiling point of a 6.95 m solution of C12H22O11 in H2O?

- Answer

-

103.6°C

Freezing point depression

The boiling point of a solution is higher than the boiling point of the pure solvent, but the opposite occurs with the freezing point. The freezing point of a solution is lower than the freezing point of the pure solvent. Think of this by assuming that solute particles interfere with solvent particles coming together to make a solid, so it takes a lower temperature to get the solvent particles to solidify. This is called freezing point depression.

The equation to calculate the change in the freezing point for a solution is similar to the equation for the boiling point elevation:

\[ΔT_f = mK_f\nonumber \]

where m is the molality of the solution and Kf is called the freezing point depression constant, which is also a characteristic of the solvent only. Several freezing point depression constants (as well as freezing point temperatures) are listed in Table \(\PageIndex{2}\).

| Liquid | Freezing Point (°C) | Kf (°C/m) |

|---|---|---|

| HC2H3O2 | 16.60 | 3.90 |

| C6H6 | 5.51 | 4.90 |

| C6H12 | 6.4 | 20.2 |

| C10H8 | 80.2 | 6.8 |

| H2O | 0.00 | 1.86 |

Remember that this equation calculates the change in the freezing point, not the new freezing point. What is calculated needs to be subtracted from the normal freezing point of the solvent, because freezing points always decrease.

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\): Freezing Point Reduction

What is the freezing point of a 1.77 m solution of CBr4 in C6H6?

Solution

We use the equation to calculate the change in the freezing point and then subtract this number from the normal freezing point of C6H6 to get the freezing point of the solution:

ΔTf = (1.77 m)(4.90°C/m) = 8.67°C

Now we subtract this number from the normal freezing point of C6H6, which is 5.51°C:

5.51 − 8.67 = −3.16°C

The freezing point of the solution is −3.16°C.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{4}\)

What is the freezing point of a 3.05 m solution of CBr4 in C10H8?

- Answer

-

59.5°C

Freezing point depression is one colligative property that we use in everyday life. Many antifreezes used in automobile radiators use solutions that have a lower freezing point than normal so that automobile engines can operate at subfreezing temperatures. We also take advantage of freezing point depression when we sprinkle various compounds on ice to thaw it in the winter for safety (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). The compounds make solutions that have a lower freezing point, so rather than forming slippery ice, any ice is liquefied and runs off, leaving a safer pavement behind.

Osmotic pressure

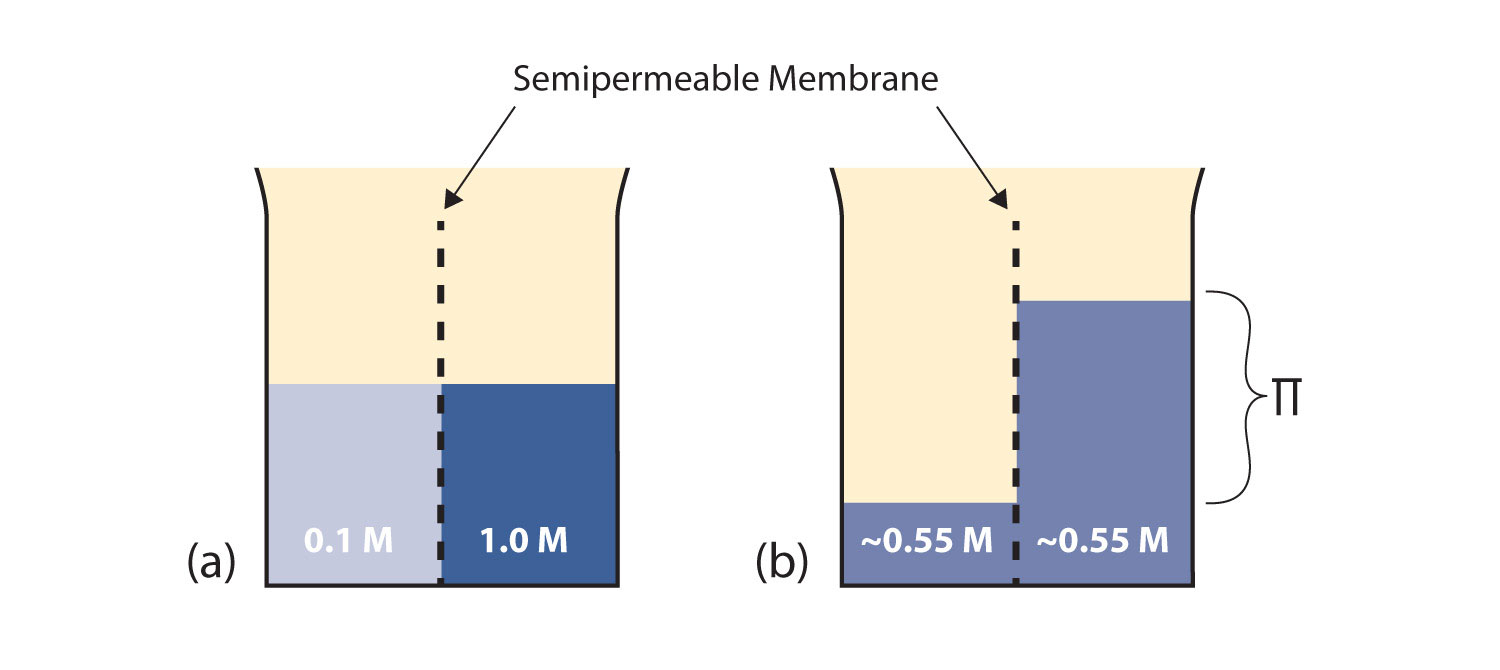

Before we introduce the final colligative property, we need to present a new concept. A semipermeable membrane is a thin membrane that will pass certain small molecules but not others. A thin sheet of cellophane, for example, acts as a semipermeable membrane. Consider the system in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\).

- A semipermeable membrane separates two solutions having the different concentrations marked. Curiously, this situation is not stable; there is a tendency for water molecules to move from the dilute side (on the left) to the concentrated side (on the right) until the concentrations are equalized, as in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\).

- This tendency is called osmosis. In osmosis, the solute remains in its original side of the system; only solvent molecules move through the semipermeable membrane. In the end, the two sides of the system will have different volumes. Because a column of liquid exerts a pressure, there is a pressure difference Π on the two sides of the system that is proportional to the height of the taller column. This pressure difference is called the osmotic pressure, which is a colligative property.

The osmotic pressure of a solution is easy to calculate:

\[\Pi = MRT\nonumber \]

where Π is the osmotic pressure of a solution, M is the molarity of the solution, R is the ideal gas law constant, and T is the absolute temperature. This equation is reminiscent of the ideal gas law we considered in Chapter 6.

Example \(\PageIndex{5}\): Osmotic Pressure

What is the osmotic pressure of a 0.333 M solution of C6H12O6 at 25°C?

Solution

First we need to convert our temperature to kelvins:

T = 25 + 273 = 298 K

Now we can substitute into the equation for osmotic pressure, recalling the value for R:

\[\prod =(0.333M)\left (0.08205\frac{L.atm}{mol.K} \right )(298K)\nonumber \]

The units may not make sense until we realize that molarity is defined as moles per liter:

\[\prod =\left ( 0.333\frac{mol}{L} \right )\left (0.08205\frac{L.atm}{mol.K} \right )(298K)\nonumber \]

Now we see that the moles, liters, and kelvins cancel, leaving atmospheres, which is a unit of pressure. Solving,

Π = 8.14 atm

This is a substantial pressure! It is the equivalent of a column of water 84 m tall.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{5}\)

What is the osmotic pressure of a 0.0522 M solution of C12H22O11 at 55°C?

- Answer

-

1.40 atm

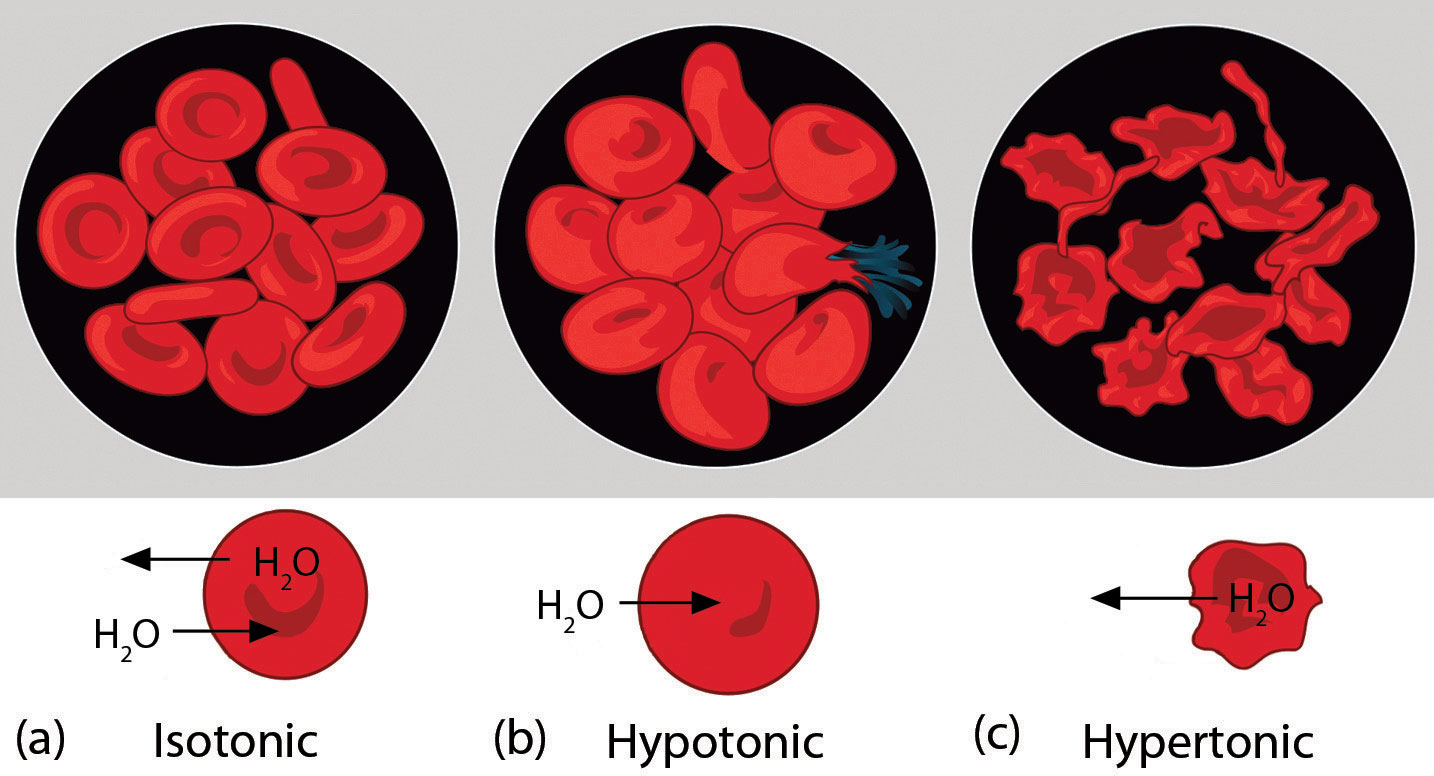

Osmotic pressure is important in biological systems because cell walls are semipermeable membranes. In particular, when a person is receiving intravenous (IV) fluids, the osmotic pressure of the fluid needs to be approximately the same as blood serum; otherwise there may be negative consequences. Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) shows three red blood cells:

- a healthy red blood cell

- a red blood cell that has been exposed to a lower concentration than normal blood serum (a so-called hypotonic solution); the cell has plumped up as solvent moves into the cell to dilute the solutes inside.

- a red blood cell exposed to a higher concentration than normal blood serum (hypertonic); water leaves the red blood cell, so it collapses onto itself. Only when the solutions inside and outside the cell are the same (isotonic) will the red blood cell be able to do its job.

Osmotic pressure is also the reason you should not drink seawater if you're stranded in a lifeboat on an ocean; seawater has a higher osmotic pressure than most of the fluids in your body. You can drink the water, but ingesting it will pull water out of your cells as osmosis works to dilute the seawater. Ironically, your cells will die of thirst, and you will also die. (It is OK to drink the water if you are stranded on a body of freshwater, at least from an osmotic pressure perspective.) Osmotic pressure is also thought to be important in getting water to the tops of tall trees, in addition to capillary action.

Summary

- Colligative properties depend only on the number of dissolved particles (that is—the concentration), not their identity.

- Raoult's law is concerned with the vapor pressure depression of solutions.

- The boiling points of solutions are always higher, and the freezing points of solutions are always lower, than those of the pure solvent.

- Osmotic pressure is caused by concentration differences between solutions separated by a semipermeable membrane and is an important biological issue.