1.7: Standard Reduction Potentials and Batteries

- Page ID

- 221441

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Learning Objectives

- Determine standard cell potentials for oxidation-reduction reactions

- Use standard reduction potentials to determine the better oxidizing or reducing agent from among several possible choices

Using batteries to measure the tendency of elements to undergo oxidation or reduction

The cell potential results from the difference in the tendency of certain redox pairs at each electrode to be reduced or oxidized. While it is impossible to quantitatively measure that tendency in terms of absolute values, we can assign an electrode the value of zero and then use it as a reference (standard electrode). Therefore, we can compare any other electrode to that standard electrode by building a battery, and measure the tendency of each electrode to be reduced in units of volts (standard potential Eº) compared to the standard electrode. This this similar to measuring the elevation of a mountain by considering the sea level as the zero point in altitude.

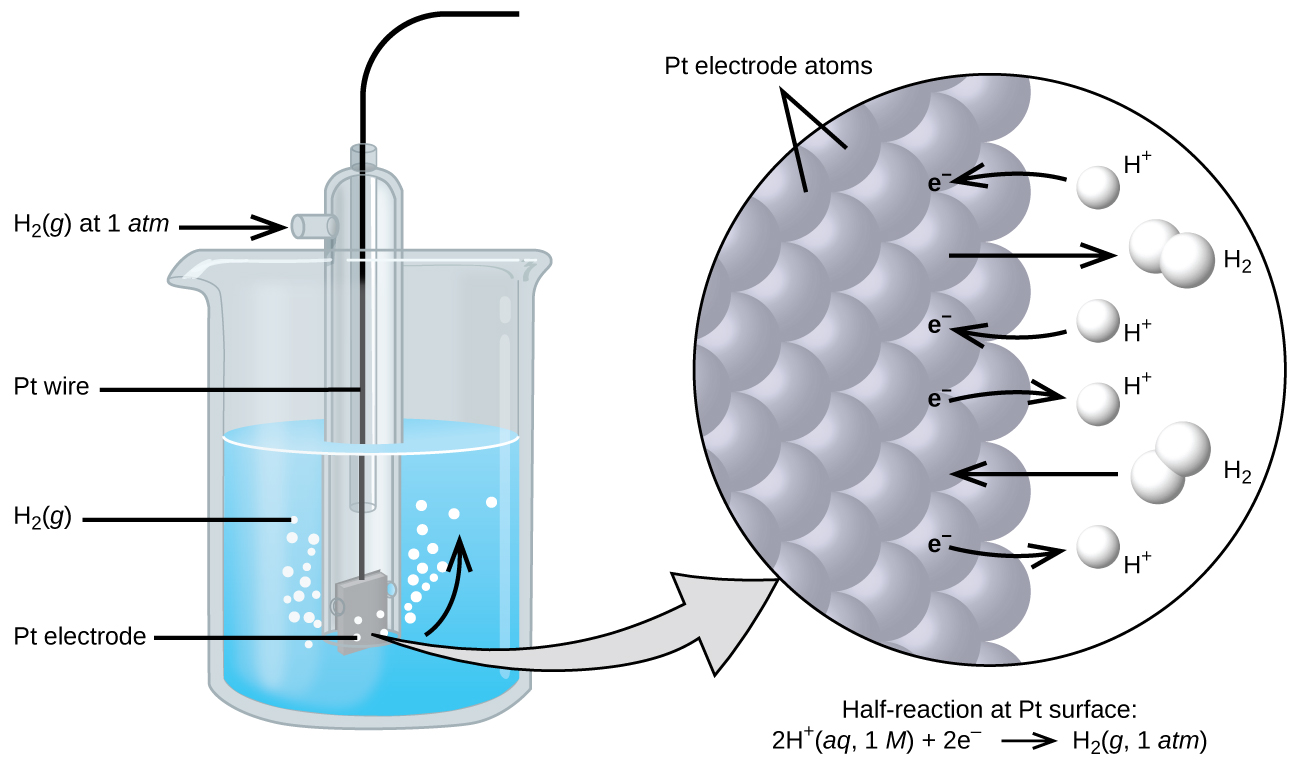

The electrode chosen as the zero voltage (standard electrode) is shown in Figure 17.4.1 and is called the standard hydrogen electrode (SHE). The SHE consists of 1 atm of hydrogen gas bubbled through a 1 M HCl solution, usually at room temperature. Platinum, which is chemically inert, is used as the electrode. The reduction half-reaction chosen as the reference is

\[\ce{2H+}(aq,\: 1\:M)+\ce{2e-}⇌\ce{H2}(g,\:1\: \ce{atm}) \hspace{20px} E°=\mathrm{0\: V}\]

E° is the standard reduction potential. The superscript “°” on the E denotes standard conditions (1 bar or 1 atm for gases, 1 M for solutes). The voltage is defined as zero for all temperatures.

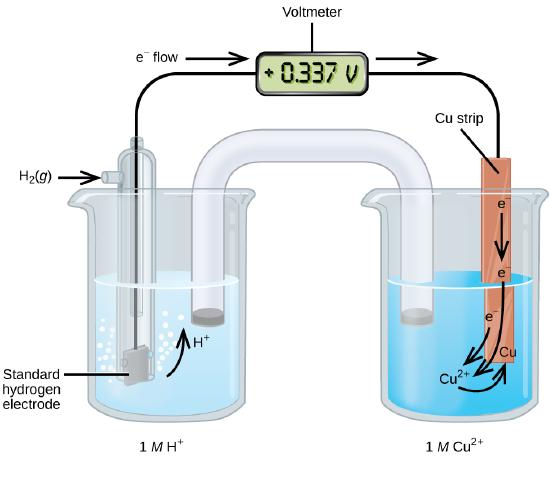

A galvanic cell consisting of a SHE and Cu2+/Cu half-cell can be used to determine the standard reduction potential for Cu2+ (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). In cell notation, the reaction is

\[\ce{Pt}(s)│\ce{H2}(g,\:1\: \ce{atm})│\ce{H+}(aq,\:1\:M)║\ce{Cu^2+}(aq,\:1\:M)│\ce{Cu}(s)\]

Electrons flow from the anode to the cathode. The reactions, which are reversible, are

&\textrm{Anode (oxidation): }\ce{H2}(g)⟶\ce{2H+}(aq) + \ce{2e-}\\

&\textrm{Cathode (reduction): }\ce{Cu^2+}(aq)+\ce{2e-}⟶\ce{Cu}(s)\\

&\overline{\textrm{Overall: }\ce{Cu^2+}(aq)+\ce{H2}(g)⟶\ce{2H+}(aq)+\ce{Cu}(s)}

\end{align*}\]

The standard reduction potential can be determined by subtracting the standard reduction potential for the reaction occurring at the anode from the standard reduction potential for the reaction occurring at the cathode. The minus sign is necessary because oxidation is the reverse of reduction.

\[E^\circ_\ce{cell}=E^\circ_\ce{cathode}−E^\circ_\ce{anode}\]

\[\mathrm{+0.34\: V}=E^\circ_{\ce{Cu^2+/Cu}}−E^\circ_{\ce{H+/H2}}=E^\circ_{\ce{Cu^2+/Cu}}−0=E^\circ_{\ce{Cu^2+/Cu}}\]

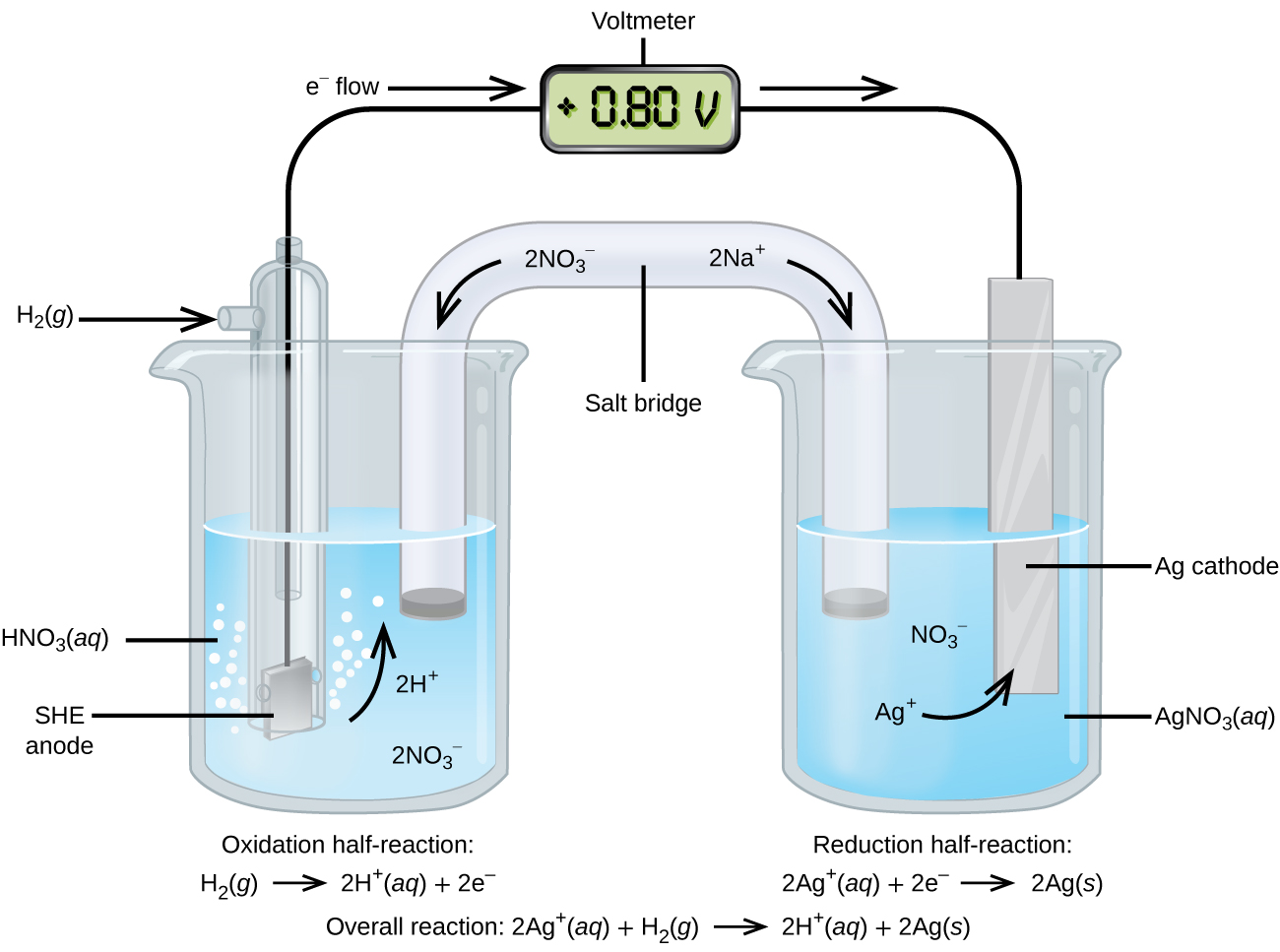

Using the SHE as a reference, other standard reduction potentials can be determined. Consider the cell shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\), where

\[\ce{Pt}(s)│\ce{H2}(g,\:1\: \ce{atm})│\ce{H+}(aq,\: 1\:M)║\ce{Ag+}(aq,\: 1\:M)│\ce{Ag}(s)\]

Electrons flow from left to right, and the reactions are

&\textrm{anode (oxidation): }\ce{H2}(g)⟶\ce{2H+}(aq)+\ce{2e-}\\

&\textrm{cathode (reduction): }\ce{2Ag+}(aq)+\ce{2e-}⟶\ce{2Ag}(s)\\

&\overline{\textrm{overall: }\ce{2Ag+}(aq)+\ce{H2}(g)⟶\ce{2H+}(aq)+\ce{2Ag}(s)}

\end{align*}\]

The standard cell potential (Eºcell) can be determined by subtracting the standard reduction potential for the reaction occurring at the anode from the standard reduction potential for the reaction occurring at the cathode. The minus sign is needed because oxidation is the reverse of reduction.

It is important to note that the potential is not doubled for the cathode reaction, even though a "2" stoichiometric coefficient is needed to balance the number of electrons exchanged. Also, the standard cell potential (Eºcell) for a battery has always a positive value, that is, Eºcell > 0 volts. That is because the redox reaction between the electrodes is spontaneous, and the electrons will circulate spontaneously according to the tendency of each electrode to be reduced or oxidized. By convention, we always compare the tendency of a particular electrode to be reduced, that is, we look at its standard reduction potential.

The SHE is rather dangerous and rarely used in the laboratory. Its main significance is that it established the zero for standard reduction potentials. Once determined, standard reduction potentials can be used to determine the standard cell potential, \(E^\circ_\ce{cell}\), for any cell. For example, for the following cell:

\[\ce{Cu}(s)│\ce{Cu^2+}(aq,\:1\:M)║\ce{Ag+}(aq,\:1\:M)│\ce{Ag}(s)\]

&\textrm{anode (oxidation): }\ce{Cu}(s)⟶\ce{Cu^2+}(aq)+\ce{2e-}\\

&\textrm{cathode (reduction): }\ce{2Ag+}(aq)+\ce{2e-}⟶\ce{2Ag}(s)\\

&\overline{\textrm{overall: }\ce{Cu}(s)+\ce{2Ag+}(aq)⟶\ce{Cu^2+}(aq)+\ce{2Ag}(s)}

\end{align*}\]

Again, note that when calculating \(E^\circ_\ce{cell}\), standard reduction potentials always remain the same even when a half-reaction is multiplied by a factor. Standard reduction potentials for selected reduction reactions are shown in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\). A more complete list is provided in Tables P1 or P2.

| Half-Reaction | E° (V) |

|---|---|

| \(\ce{F2}(g)+\ce{2e-}⟶\ce{2F-}(aq)\) | +2.866 |

| \(\ce{PbO2}(s)+\ce{SO4^2-}(aq)+\ce{4H+}(aq)+\ce{2e-}⟶\ce{PbSO4}(s)+\ce{2H2O}(l)\) | +1.69 |

| \(\ce{MnO4-}(aq)+\ce{8H+}(aq)+\ce{5e-}⟶\ce{Mn^2+}(aq)+\ce{4H2O}(l)\) | +1.507 |

| \(\ce{Au^3+}(aq)+\ce{3e-}⟶\ce{Au}(s)\) | +1.498 |

| \(\ce{Cl2}(g)+\ce{2e-}⟶\ce{2Cl-}(aq)\) | +1.35827 |

| \(\ce{O2}(g)+\ce{4H+}(aq)+\ce{4e-}⟶\ce{2H2O}(l)\) | +1.229 |

| \(\ce{Pt^2+}(aq)+\ce{2e-}⟶\ce{Pt}(s)\) | +1.20 |

| \(\ce{Br2}(aq)+\ce{2e-}⟶\ce{2Br-}(aq)\) | +1.0873 |

| \(\ce{Ag+}(aq)+\ce{e-}⟶\ce{Ag}(s)\) | +0.7996 |

| \(\ce{Hg2^2+}(aq)+\ce{2e-}⟶\ce{2Hg}(l)\) | +0.7973 |

| \(\ce{Fe^3+}(aq)+\ce{e-}⟶\ce{Fe^2+}(aq)\) | +0.771 |

| \(\ce{MnO4-}(aq)+\ce{2H2O}(l)+\ce{3e-}⟶\ce{MnO2}(s)+\ce{4OH-}(aq)\) | +0.558 |

| \(\ce{I2}(s)+\ce{2e-}⟶\ce{2I-}(aq)\) | +0.5355 |

| \(\ce{NiO2}(s)+\ce{2H2O}(l)+\ce{2e-}⟶\ce{Ni(OH)2}(s)+\ce{2OH-}(aq)\) | +0.49 |

| \(\ce{Cu^2+}(aq)+\ce{2e-}⟶\ce{Cu}(s)\) | +0.34 |

| \(\ce{Hg2Cl2}(s)+\ce{2e-}⟶\ce{2Hg}(l)+\ce{2Cl-}(aq)\) | +0.26808 |

| \(\ce{AgCl}(s)+\ce{e-}⟶\ce{Ag}(s)+\ce{Cl-}(aq)\) | +0.22233 |

| \(\ce{Sn^4+}(aq)+\ce{2e-}⟶\ce{Sn^2+}(aq)\) | +0.151 |

| \(\ce{2H+}(aq)+\ce{2e-}⟶\ce{H2}(g)\) | 0.00 |

| \(\ce{Pb^2+}(aq)+\ce{2e-}⟶\ce{Pb}(s)\) | −0.1262 |

| \(\ce{Sn^2+}(aq)+\ce{2e-}⟶\ce{Sn}(s)\) | −0.1375 |

| \(\ce{Ni^2+}(aq)+\ce{2e-}⟶\ce{Ni}(s)\) | −0.257 |

| \(\ce{Co^2+}(aq)+\ce{2e-}⟶\ce{Co}(s)\) | −0.28 |

| \(\ce{PbSO4}(s)+\ce{2e-}⟶\ce{Pb}(s)+\ce{SO4^2-}(aq)\) | −0.3505 |

| \(\ce{Cd^2+}(aq)+\ce{2e-}⟶\ce{Cd}(s)\) | −0.4030 |

| \(\ce{Fe^2+}(aq)+\ce{2e-}⟶\ce{Fe}(s)\) | −0.447 |

| \(\ce{Cr^3+}(aq)+\ce{3e-}⟶\ce{Cr}(s)\) | −0.744 |

| \(\ce{Mn^2+}(aq)+\ce{2e-}⟶\ce{Mn}(s)\) | −1.185 |

| \(\ce{Zn(OH)2}(s)+\ce{2e-}⟶\ce{Zn}(s)+\ce{2OH-}(aq)\) | −1.245 |

| \(\ce{Zn^2+}(aq)+\ce{2e-}⟶\ce{Zn}(s)\) | −0.7618 |

| \(\ce{Al^3+}(aq)+\ce{3e-}⟶\ce{Al}(s)\) | −1.662 |

| \(\ce{Mg^2+}(aq)+\ce{2e-}⟶\ce{Mg}(s)\) | −2.372 |

| \(\ce{Na+}(aq)+\ce{e-}⟶\ce{Na}(s)\) | −2.71 |

| \(\ce{Ca^2+}(aq)+\ce{2e-}⟶\ce{Ca}(s)\) | −2.868 |

| \(\ce{Ba^2+}(aq)+\ce{2e-}⟶\ce{Ba}(s)\) | −2.912 |

| \(\ce{K+}(aq)+\ce{e-}⟶\ce{K}(s)\) | −2.931 |

| \(\ce{Li+}(aq)+\ce{e-}⟶\ce{Li}(s)\) | −3.04 |

Tables like this make it possible to determine the standard cell potential for many oxidation-reduction reactions. The higher the standard reduction potential, the higher the tendency of that electrode to be reduced. All electrodes with a positive standard reduction potential value have a higher tendency than hydrogen to be reduced, while all electrodes with a negative standard reduction potential have less tendency than hydrogen to be reduced.

Since the standard reduction potential is a measure of a particular electrode (redox couple) to be reduced, we can use this value to determine which electrode will be the cathode and which electrode will be anode when building an electrochemical cell using two electrodes listed on the table above. We can also use the standard reduction potential of each electrode to calculate the resulting standard cell potential (Eºcell). See the following example:

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Cell Potentials from Standard Reduction Potentials

What is the standard cell potential for a galvanic cell that consists of Au3+/Au and Ni2+/Ni half-cells? Identify the cathode and anode.

Solution

Using Table \(\PageIndex{1}\), the reactions involved in the galvanic cell, both written as reductions, are

\[\ce{Au^3+}(aq)+\ce{3e-}⟶\ce{Au}(s) \hspace{20px} E^\circ_{\ce{Au^3+/Au}}=\mathrm{+1.498\: V}\]

\[\ce{Ni^2+}(aq)+\ce{2e-}⟶\ce{Ni}(s) \hspace{20px} E^\circ_{\ce{Ni^2+/Ni}}=\mathrm{−0.257\: V}\]

Galvanic cells have positive cell potentials, and all the reduction reactions are reversible. The reaction at the anode will be the half-reaction with the smaller or more negative standard reduction potential. Reversing the reaction at the anode (to show the oxidation) but not its standard reduction potential gives:

\[\begin{align*}

&\textrm{Anode (oxidation): }\ce{Ni}(s)⟶\ce{Ni^2+}(aq)+\ce{2e-} \hspace{20px} E^\circ_\ce{anode}=E^\circ_{\ce{Ni^2+/Ni}}=\mathrm{−0.257\: V}\\

&\textrm{Cathode (reduction): }\ce{Au^3+}(aq)+\ce{3e-}⟶\ce{Au}(s) \hspace{20px} E^\circ_\ce{cathode}=E^\circ_{\ce{Au^3+/Au}}=\mathrm{+1.498\: V}

\end{align*}\]

The least common factor is six, so the overall reaction is

The reduction potentials are not scaled by the stoichiometric coefficients when calculating the cell potential, and the unmodified standard reduction potentials must be used.

From the half-reactions, Ni is oxidized, so it is the anode (or the reducing agent), and Au3+ is reduced, so it is the cathode (or the oxidizing agent). The resulting standard cell potential (Eºcell) is 1.755 V. As expected, this value is positive since we are working with a galvanic or electrochemical cell.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

A galvanic cell consists of a Mg electrode in 1 M Mg(NO3)2 solution and a Ag electrode in 1 M AgNO3 solution. Calculate the standard cell potential at 25 °C.

- Answer

-

\[\ce{Mg}(s)+\ce{2Ag+}(aq)⟶\ce{Mg^2+}(aq)+\ce{2Ag}(s) \hspace{20px} E^\circ_\ce{cell}=\mathrm{0.7996\: V−(−2.372\: V)=3.172\: V} \nonumber\]

Contributors and Attributions

Summary

Assigning the potential of the standard hydrogen electrode (SHE) as zero volts allows the determination of standard reduction potentials, E°, for half-reactions in electrochemical cells. As the name implies, standard reduction potentials use standard states (1 bar or 1 atm for gases; 1 M for solutes, often at 298.15 K) and are written as reductions (where electrons appear on the left side of the equation). The reduction reactions are reversible, so standard cell potentials can be calculated by subtracting the standard reduction potential for the reaction at the anode from the standard reduction for the reaction at the cathode. When calculating the standard cell potential, the standard reduction potentials are not scaled by the stoichiometric coefficients in the balanced overall equation.

Key Equations

- \(E^\circ_\ce{cell}=E^\circ_\ce{cathode}−E^\circ_\ce{anode}\)

Glossary

- standard cell potential \( (E^\circ_\ce{cell})\)

- the cell potential when all reactants and products are in their standard states (1 bar or 1 atm or gases; 1 M for solutes), usually at 298.15 K; can be calculated by subtracting the standard reduction potential for the half-reaction at the anode from the standard reduction potential for the half-reaction occurring at the cathode

- standard hydrogen electrode (SHE)

- the electrode consists of hydrogen gas bubbling through hydrochloric acid over an inert platinum electrode whose reduction at standard conditions is assigned a value of 0 V; the reference point for standard reduction potentials

- standard reduction potential (E°)

- the value of the reduction under standard conditions (1 bar or 1 atm for gases; 1 M for solutes) usually at 298.15 K; tabulated values used to calculate standard cell potentials

Contributors and Attributions

Paul Flowers (University of North Carolina - Pembroke), Klaus Theopold (University of Delaware) and Richard Langley (Stephen F. Austin State University) with contributing authors. Textbook content produced by OpenStax College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 license. Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/85abf193-2bd...a7ac8df6@9.110).