1.4: The Kinetic Molecular Theory of Ideal Gases

- Page ID

- 164730

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Skills to Develop

- State the postulates of the kinetic-molecular theory

- Use this theory’s postulates to explain the gas laws

The gas laws that we have seen to this point, as well as the ideal gas equation, are empirical, that is, they have been derived from experimental observations. The mathematical forms of these laws closely describe the macroscopic behavior of most gases at pressures less than about 1 or 2 atm. Although the gas laws describe relationships that have been verified by many experiments, they do not tell us why gases follow these relationships.

The kinetic molecular theory (KMT) is a simple microscopic model that effectively explains the gas laws we have described. This theory is based on the following five postulates described here. (Note: The term “molecule” will be used to refer to the individual chemical species that compose the gas, although some gases are composed of atomic species, for example, the noble gases.)

Postulates of the Kinetic Molecular Theory

- Gases are composed of molecules that are in continuous motion, travelling in straight lines and changing direction only when they collide with other molecules or with the walls of a container.

- The molecules composing the gas are negligibly small compared to the distances between them.

- The pressure exerted by a gas in a container results from collisions between the gas molecules and the container walls.

- Gas molecules exert no attractive or repulsive forces on each other or the container walls; therefore, their collisions are elastic (do not involve a loss of energy).

- The average kinetic energy of the gas molecules is proportional to the kelvin temperature of the gas.

The test of the KMT and its postulates is its ability to explain and describe the behavior of a gas. The various gas laws can be derived from the assumptions of the KMT, which have led chemists to believe that the assumptions of the theory accurately represent the properties of gas molecules. We will first look at the individual gas laws (Boyle’s, Charles’s, Amontons’s, Avogadro’s, and Dalton’s laws) conceptually to see how the KMT explains them. Then, we will more carefully consider the relationships between molecular masses, speeds, and kinetic energies with temperature.

The Kinetic Molecular Theory Explains the Behavior of Gases

According to the KMT, gas pressure is exerted by rapidly moving gas molecules colliding with the walls of their container. Because of this, two things determine the pressure of a gas: 1) the number of molecules hitting a unit area of the wall per unit of time, and 2) the kinetic energy of the collisions - in other words, "how hard" the molecules are hitting the wall. This simple idea conceptually explains the behavior of gases as described by the gas laws:

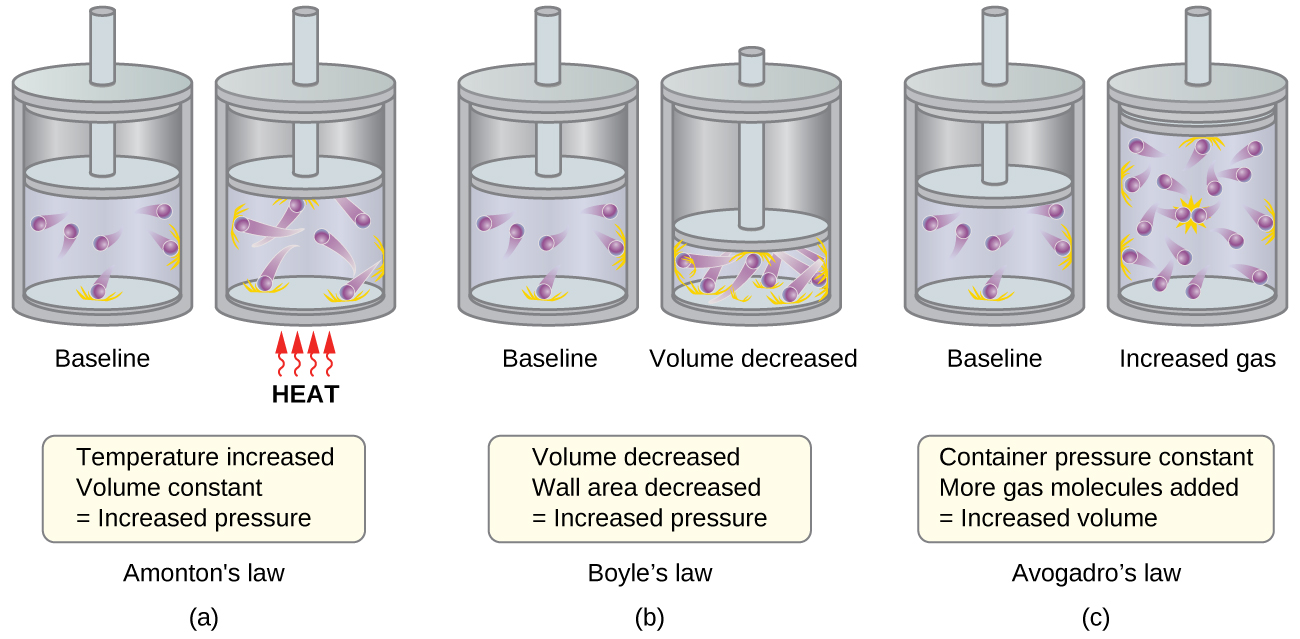

- Amontons’s law. If the temperature is increased, the average speed and kinetic energy of the gas molecules increase. If the volume is held constant, the increased speed of the gas molecules results in more frequent and more forceful collisions with the walls of the container, therefore increasing the pressure (Figure \(\PageIndex{1a}\)).

- Charles’s law. If the temperature of a gas is increased, a constant pressure may be maintained only if the volume occupied by the gas increases. This will result in greater average distances traveled by the molecules to reach the container walls, as well as increased wall surface area. These conditions will decrease both the frequency of molecule-wall collisions and the number of collisions per unit area, the combined effects of which balance the effect of increased collision forces due to the greater kinetic energy at the higher temperature.

- Boyle’s law. If the gas volume is decreased, the container wall area decreases and the molecule-wall collision frequency increases, both of which increase the pressure exerted by the gas (Figure \(\PageIndex{1b}\)).

- Avogadro’s law. At constant pressure and temperature, the frequency and force of molecule-wall collisions are constant. Under such conditions, increasing the number of gaseous molecules will require a proportional increase in the container volume in order to yield a decrease in the number of collisions per unit area to compensate for the increased frequency of collisions (Figure \(\PageIndex{1c}\)).

Molecular Velocities and Kinetic Energy

The previous discussion showed that the KMT qualitatively explains the behaviors described by the various gas laws. The postulates of this theory may be applied in a more quantitative fashion to derive these individual laws. To do this, we must first look at velocities and kinetic energies of gas molecules, and the temperature of a gas sample.

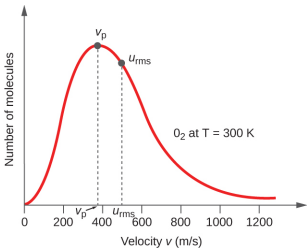

In a gas sample, individual molecules have widely varying speeds; however, because of the vast number of molecules and collisions involved, the molecular speed distribution and average speed are constant. This molecular speed distribution is known as a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution, and it depicts the relative numbers of molecules in a bulk sample of gas that possesses a given speed (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)).

The kinetic energy (KE) of a particle of mass (m) and speed (u) is given by:

Expressing mass in kilograms and speed in meters per second will yield energy values in units of joules (J = kg m2 s–2). To deal with a large number of gas molecules, we use averages for both speed and kinetic energy. In the KMT, the root mean square velocity of a particle, urms, is defined as the square root of the average of the squares of the velocities with n = the number of particles:

The average kinetic energy, KEavg, is then equal to:

The KEavg of a collection of gas molecules is also directly proportional to the temperature of the gas and may be described by the equation:

where R is the gas constant and T is the kelvin temperature. When used in this equation, the appropriate form of the gas constant is 8.3145 J mol-1K-1 (8.3145 kg m2s–2mol-1K–1). These two separate equations for KEavg may be combined and rearranged to yield a relation between molecular speed and temperature:

\[u_\ce{rms}=\sqrt{\dfrac{3RT}{m}} \label{RMS}\]

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Calculation of urms

Calculate the root-mean-square velocity for a nitrogen molecule at 30 °C.

Solution

Convert the temperature into Kelvin:

Determine the mass of a nitrogen molecule in kilograms:

\[\mathrm{\dfrac{28.0\cancel{g}}{1\: mol}×\dfrac{1\: kg}{1000\cancel{g}}=0.028\:kg/mol}\]

Replace the variables and constants in the root-mean-square velocity formula (Equation \ref{RMS}), replacing Joules with the equivalent kg m2s–2:

\[ \begin{align} u_\ce{rms} &= \sqrt{\dfrac{3RT}{m}} \\ u_\ce{rms} &=\sqrt{\dfrac{3(8.314\:J/mol\: K)(303\: K)}{(0.028\:kg/mol)}} \\ &=\sqrt{2.70 \times 10^5\:m^2s^{−2}} \\ &= 519\:m/s \end{align} \]

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Calculate the root-mean-square velocity for an oxygen molecule at –23 °C.

- Answer

-

441 m/s

If the temperature of a gas increases, its KEavg increases, more molecules have higher speeds and fewer molecules have lower speeds, and the distribution shifts toward higher speeds overall, that is, to the right. If temperature decreases, KEavg decreases, more molecules have lower speeds and fewer molecules have higher speeds, and the distribution shifts toward lower speeds overall, that is, to the left. This behavior is illustrated for nitrogen gas in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\).

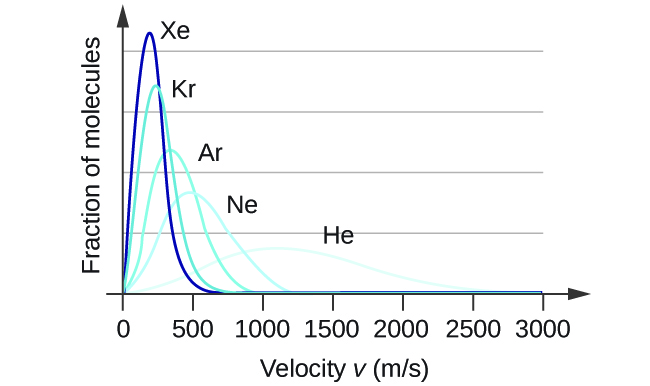

At a given temperature, all gases have the same KEavg for their molecules. Gases composed of lighter molecules have more high-speed particles and a higher urms, with a speed distribution that peaks at relatively higher velocities. Gases consisting of heavier molecules have more low-speed particles, a lower urms, and a speed distribution that peaks at relatively lower velocities. This trend is demonstrated by the data for a series of noble gases shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\). Lighter gas molecules move faster on average and heavier gas molecules move slower on average. However, the average kinetic energy depends only on the temperature, not the identity of the gas.

The gas simulator may be used to examine the effect of temperature on molecular velocities. Examine the simulator’s “energy histograms” (molecular speed distributions) and “species information” (which gives average speed values) for molecules of different masses at various temperatures.

Application: Graham's Law of Effusion

According to the KMT, the molecules of a gas are in rapid motion and the molecules themselves are small. The average distance between the molecules of a gas is large compared to the size of the molecules. As a consequence, gas molecules can move past each other easily and diffuse through space at relatively fast rates. "Effusion" is the process by which a gas escapes a container from a small hole.

Graham's Law of effusion relates the rate of effusion of a gas to its molecular mass. It should make sense that a faster-moving gas is able to escape its container more quickly (higher rate of effusion). In light of the kinetic molecular theory, we know that lighter gas molecules move faster than heavier molecules on average at the same temperature, therefore lighter molecules will have faster rates of effusion.

Mathematically, the relationship is not a simple linear correlation between mass and rate of effusion, however. The rate of effusion of a gas does depend directly on the (average) speed of its molecules:

Using this relation, and the equation relating molecular speed to mass, Graham’s law may be easily derived as shown here:

\[u_\ce{rms}=\sqrt{\dfrac{3RT}{m}}\]

\[m=\dfrac{3RT}{u^2_\ce{rms}}=\dfrac{3RT}{\overline{u}^2}\]

\[\mathrm{\dfrac{effusion\: rate\: A}{effusion\: rate\: B}}=\dfrac{u_\mathrm{rms\:A}}{u_\mathrm{rms\:B}}=\dfrac{\sqrt{\dfrac{3RT}{m_\ce{A}}}}{\sqrt{\dfrac{3RT}{m_\ce{B}}}}=\sqrt{\dfrac{m_\ce{B}}{m_\ce{A}}}\]

The ratio of the rates of effusion is thus derived to be inversely proportional to the ratio of the square roots of their masses. This is the same relation observed experimentally and expressed as Graham’s law.

Rates of effusion and diffusion are some of the few properties of gases that depend on the identity of the gas molecules and can therefore be used to distinguish different gases in a mixture. This property is taken advantage of in gaseous diffusion technology for nuclear fuel enrichment. Gaseous uranium hexafluoride molecules are diffused repeatedly through membranes, slowly separating out the lighter, fissile uranium-235 isotope from the heavier, non-fissile uranium-238.

_(cropped).jpg)

_(cropped).jpg)

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\): Gaseous diffusion process for uranium refinement. Image by Nuclear Regulatory Commission from US [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]

What is an "Ideal Gas"?

The kinetic molecular theory defines what is meant by "ideal gas behavior". Ideal gases perfectly exemplify the following assumptions from the KMT:

1) Ideal gas particles are so small compared to the distance between them that the volume of the molecules themselves can be ignored.

2) Ideal gas particles have no attractions or repulsions for each other or for the walls of the container.

When these assumptions hold true, a gas will perfectly obey the ideal gas law, PV = nRT. These assumptions of the KMT generally do a good job of describing gas behavior at relatively low pressures and moderate temperatures - in other words, most "normal" conditions. We will see in a later module how the behavior of "real" gases begins to change when these assumptions become less accurate.

Importantly, the ideal gas law implies that only the number of moles of gas molecules, not their identity, determines the properties of the gas.

Summary

The kinetic molecular theory is a simple but very effective model that effectively explains ideal gas behavior. The theory assumes that gases consist of widely separated molecules of negligible volume that are in constant motion, colliding elastically with one another and the walls of their container with average velocities determined by their absolute temperatures. The individual molecules of a gas exhibit a range of velocities, the distribution of these velocities being dependent on the temperature of the gas and the mass of its molecules.

Key Equations

- \(\mathrm{KE_{avg}}=\dfrac{3}{2}RT\)

- \(u_\ce{rms}=\sqrt{\dfrac{3RT}{m}}\)

Glossary

- kinetic molecular theory

- theory based on simple principles and assumptions that effectively explains ideal gas behavior

- root mean square velocity (urms)

- measure of average velocity for a group of particles calculated as the square root of the average squared velocity

Contributors

Paul Flowers (University of North Carolina - Pembroke), Klaus Theopold (University of Delaware) and Richard Langley (Stephen F. Austin State University) with contributing authors. Textbook content produced by OpenStax College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 license. Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/85abf193-2bd...a7ac8df6@9.110).

- Anna Christianson, Bellarmine University