11.3: Ionic Bonds

- Page ID

- 289425

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)⚙️ Learning Objectives

- State the octet rule.

- Define ionic bond.

- Draw Lewis structures for ionic compounds.

Back in Section 4.8, we discussed the formation of ions. It wasn't emphasized at that time, but it turns out that most monoatomic ions have eight valence electrons. Anions form when atoms gain enough electrons to wind up with a total of eight electrons in the valence shell. Anions carry a negative charge due to the gain of negatively charged electrons. Cations form when atoms lose all of the electrons from their original valence shell, revealing a new valence shell that contains eight valence electrons that lies just below the original valence shell. Cations carry a positive charge due to the loss of negatively charged electrons. For whatever reason, having eight valence electrons is a particularly energetically stable arrangement of electrons.

The octet rule explains the favorable trend of atoms having eight electrons in their valence shell, as is the case for neutral atoms of all of the noble gases, except for helium. The first energy level holds a maximum of two electrons, so atoms of helium may only have a maximum of two valence electrons. When atoms form compounds, the octet rule is not always satisfied for all atoms at all times, but it is a very good rule of thumb for understanding the kinds of bonding arrangements that atoms can make.

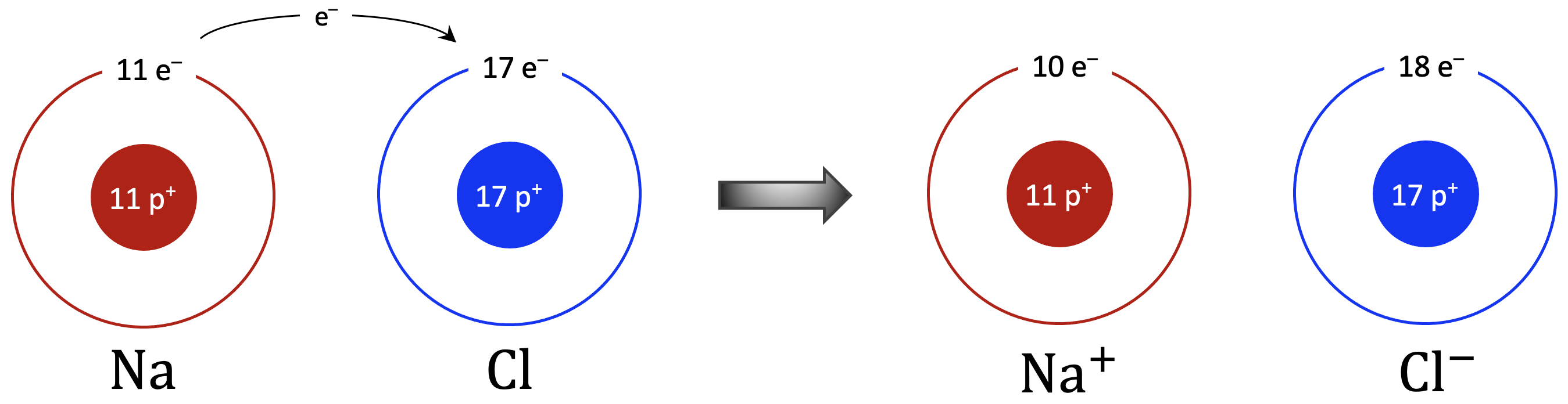

Let's consider a sodium atom in the presence of a chlorine atom. The two atoms have these Lewis diagrams:

\({\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}\mathrm {Na}}{\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}\,}{\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}⋅}\;\;\;{\color[rgb]{0.0, 0.0, 1.0}\overset{⬝\,⬝}{\underset⬝{:\mathrm{Cl}:}}}\)

For the sodium atom to obtain an octet, it must lose a valence electron to give it the same number of valence electrons as a neutral neon atom. For the chlorine atom to obtain an octet, it must gain a valence electron to give it the same number of valence electrons as a neutral argon atom. Remember that the identity of an element is based on the number of protons in the nucleus, not on the number of electrons in the electron cloud.

An electron transfers from the sodium atom to the chlorine atom:

\({\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}\mathrm {Na}}{\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}\,}{\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}⋅}\leadsto\;{\color[rgb]{0.0, 0.0, 1.0}\overset{⬝\,⬝}{\underset⬝{:\mathrm{Cl}:}}}\)

The sodium atom now has one less electron than it has protons, making the sodium ion have a positive charge, Na+, while the chlorine atom has one more electron than it has protons, making the chloride ion have a negative charge, Cl−. Since opposite charges attract, the Na+ and Cl− ions come together to make sodium chloride with the Lewis structure:

\({\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}\mathrm {Na}}{\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}\,}^{\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}+}\;\;{\color[rgb]{0.0, 0.0, 1.0}\;}{\color[rgb]{0.0, 0.0, 1.0}\left[\overset{⬝\,⬝}{\underset{⬝\,⬝}{:\mathrm{Cl}:}}\;\right]}^{\color[rgb]{0.0, 0.0, 1.0}-}\)

The attraction between oppositely charged ions is called an ionic bond, which is one of the main types of chemical bonds in chemistry. Ionic bonds are caused by the transfer of electrons from one atom to another, typically from a metal to a nonmetal. In addition, since sodium and chlorine now have complete octets they are energetically stable.

⚓️ Ionic Bond

A chemical bond that forms between oppositely charged ions and is caused by the transfer of electrons from one atom to another, typically from a metal to a nonmetal.

When writing Lewis structure for ionic compounds, the convention is to place square brackets, [ ], around an ion to separate dots from the charge on the ion, which is still written as a superscript. This is why the square brackets are placed around the chloride ion, Cl− (which is surrounded by dots), while they are not placed around the sodium ion, Na+ (which is not surrounded by dots).

From here, it is easy to see why the chemical formula of sodium chloride is NaCl. As per the convention for writing formulas for ionic compounds, charges are left off of the chemical formula:

\({\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}\mathrm {Na}}{\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}\,}^{\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}+}\;+\;{\color[rgb]{0.0, 0.0, 1.0}\;}{\color[rgb]{0.0, 0.0, 1.0}\left[\overset{⬝\,⬝}{\underset{⬝\,⬝}{:\mathrm{Cl}:}}\;\right]}^{\color[rgb]{0.0, 0.0, 1.0}-}\Rightarrow\;\;\mathrm{Na}^+\mathrm{Cl}^-\;\;\Rightarrow\;\;\;\mathrm{NaCl}\)

In electron transfer, the number of electrons lost must equal the number of electrons gained, as shown in the formation of NaCl.

A similar process occurs between magnesium atoms and oxygen atoms. For the magnesium atom to obtain an octet, it must lose two valence electrons to give it the same number of valence electrons as a neutral neon atom. For the oxygen atom to obtain an octet, it must gain two valence electrons to give it the same number of valence electrons as a neutral argon atom. Once again, remember that the identity of an element is based on the number of protons in the nucleus, not on the number of electrons in the electron cloud.

\({\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}\overset⬝{\underset⬝{\mathrm{Mg}}}}\;\begin{array}{c}\leadsto\\\leadsto\end{array}\;{\color[rgb]{0.0, 0.0, 1.0}\overset⬝{\underset⬝{:\mathrm O:}}}\)

This provides both magnesium and oxygen with complete octets. The magnesium atom now has two less electrons than it has protons, making the magnesium ion have a 2+ charge, while the oxygen atom has two more electrons than it has protons, making the oxide ion have a 2– charge. Since opposite charges attract, the Mg2+ and O2− ions come together to make magnesium oxide with the Lewis structure:

\({\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}\mathrm {Mg}}^{\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}{2+}}\;\;{\color[rgb]{0.0, 0.0, 1.0}\left[\overset{⬝\,⬝}{\underset{⬝\,⬝}{:\mathrm O:}}\right]}^{\color[rgb]{0.0, 0.0, 1.0}{2-}}\)

From here, it is easy to see why the formula of magnesium oxide is MgO:

\({\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}\mathrm {Mg}}{\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}\,}^{\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}{2+}}\;+\;{\color[rgb]{0.0, 0.0, 1.0}\;}{\color[rgb]{0.0, 0.0, 1.0}\left[\overset{⬝\,⬝}{\underset{⬝\,⬝}{:\mathrm O:}}\;\right]}^{\color[rgb]{0.0, 0.0, 1.0}{2-}}\Rightarrow\;\;\mathrm{Mg}^{2+}\mathrm O^{2-}\;\;\Rightarrow\;\;\;\mathrm{MgO}\)

What happens when sodium atoms get together with oxygen atoms? An oxygen atom needs two electrons to complete its valence shell, while a sodium atom is only able to supply one electron:

\({\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}\mathrm {Na}}{\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}\,}{\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}⋅}\leadsto\;{\color[rgb]{0.0, 0.0, 1.0}\overset{⬝\,⬝}{\underset⬝{⋅\,\mathrm{O}:}}}\)

This does not provide an oxygen atom with a complete octet. Therefore, a second sodium atom is needed to provide a second electron for the oxygen atom:

\({\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}\begin{array}{c}\mathrm{Na}\,⋅\\\mathrm{Na}\,⋅\end{array}}\begin{array}{c}\leadsto\\\leadsto\end{array}\;{\color[rgb]{0.0, 0.0, 1.0}\overset⬝{\underset⬝{:\mathrm O:}}}\)

The result is the formation of two sodium ions, Na+, and one oxide ion, O2–, that come together to make sodium oxide with the Lewis structure:

\({\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}\begin{array}{c}\mathrm{Na}^+\\\mathrm{Na}^+\end{array}}\;\;{\color[rgb]{0.0, 0.0, 1.0}\left[\overset{⬝\,⬝}{\underset{⬝\,⬝}{:\mathrm O:}}\right]}^{\color[rgb]{0.0, 0.0, 1.0}{2-}}\)

The resulting structure reflects the fact that the number of electrons lost by the sodium atoms must equal the number of electrons gained by the oxygen atom. It also shows that the compound is charge-balanced and why the ratio of sodium ions to oxide ions is 2:1 in sodium oxide:

\({\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}\begin{array}{c}\mathrm{Na}^+\\\mathrm{Na}^+\end{array}}+{\color[rgb]{0.0, 0.0, 1.0}\left[\overset{⬝\,⬝}{\underset{⬝\,⬝}{:\mathrm O:}}\right]}^{\color[rgb]{0.0, 0.0, 1.0}{2-}}\Rightarrow\;\;\mathrm{Na}_2^+\mathrm O^{2-}\;\Rightarrow\;\;{\mathrm{Na}}_2\mathrm O\)

It is an expectation that the number of electrons lost by metal atoms must equal the number of electrons gained by nonmetal atoms, according to the law of conservation of mass. This will always be reflected in the Lewis structure of ionic compounds. It also explains why ionic compounds must be charge-balanced and why they have the ratios of cations to anions that they do.

✅ Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Barium Bromide

Write the Lewis structure for barium bromide. Use arrows to illustrate the transfer of electrons to form barium bromide from barium atoms and bromine atoms.

Solution

A Ba atom has two valence electrons, while a Br atom has seven electrons. A Br atom needs only one more to complete its octet, while Ba atoms must lose two electrons. Thus we need two Br atoms to accept the two electrons from one Ba atom. The transfer process looks as follows:

\({\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}\overset⬝{\underset⬝{\mathrm{Ba}}}}\;\begin{array}{c}\leadsto\\\leadsto\end{array}\;{\color[rgb]{0.0, 0.0, 1.0}\begin{array}{c}\overset{⬝\,⬝}{\underset{⬝\,⬝}{⋅\,\mathrm{Br}:}}\\\overset{⬝\,⬝}{\underset{⬝\,⬝}{⋅\,\mathrm{Br}:}}\end{array}}\)

Lewis structure: \({\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}\mathrm {Ba}}{\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}\,}^{\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}{2+}}\;\;{\color[rgb]{0.0, 0.0, 1.0}\begin{array}{c}\left[\overset{⬝\,⬝}{\underset{⬝\,⬝}{:\mathrm{Br}:}}\;\right]^-\\\left[\overset{⬝\,⬝}{\underset{⬝\,⬝}{:\mathrm{Br}:}}\;\right]^-\end{array}}\)

\({\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}\mathrm {Ba}}{\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}\,}^{\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}{2+}}\;+\;{\color[rgb]{0.0, 0.0, 1.0}\begin{array}{c}\left[\overset{⬝\,⬝}{\underset{⬝\,⬝}{:\mathrm{Br}:}}\;\right]^-\\\left[\overset{⬝\,⬝}{\underset{⬝\,⬝}{:\mathrm{Br}:}}\;\right]^-\end{array}}\;\Rightarrow\;\mathrm{Ba}^{2+}\mathrm{Br}_2^-\;\Rightarrow\;{\mathrm{BaBr}}_2\)

The oppositely charged ions attract each other to make BaBr2.

✏️ Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Write the Lewis structure for:

- lithium fluoride

- aluminum oxide

- Answer A

- \(\mathrm{Li}^+\;\;\left[\overset{⬝\,⬝}{\underset{⬝\,⬝}{:\mathrm F:}}\right]^-\)

- Answer B

- \(\begin{array}{c}\mathrm{Al}^{3+}\\\mathrm{Al}^{3+}\end{array}\;\;\begin{array}{c}\left[\overset{⬝\,⬝}{\underset{⬝\,⬝}{:\mathrm O:}}\right]^{2-}\\\left[\overset{⬝\,⬝}{\underset{⬝\,⬝}{:\mathrm O:}}\right]^{2-}\\\left[\overset{⬝\,⬝}{\underset{⬝\,⬝}{:\mathrm O:}}\right]^{2-}\end{array}\)

✏️ Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Write the Lewis structure for potassium phosphide. Use arrows to illustrate the transfer of electrons to form potassium phosphide from potassium atoms and phosphorus atoms.

- Answer

- \({\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}\begin{array}{c}\mathrm K\,⋅\\\mathrm K\,⋅\\\mathrm K\,⋅\end{array}}\begin{array}{c}\leadsto\\\leadsto\\\leadsto\end{array}\;{\color[rgb]{0.0, 0.0, 1.0}\overset⬝{\underset⬝{⋅\,\mathrm P:}}}\)

Lewis structure: \({\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}\begin{array}{c}\mathrm K^+\\\mathrm K^+\\\mathrm K^+\end{array}}\;\;\;{\color[rgb]{0.0, 0.0, 1.0}\left[\overset{⬝\,⬝}{\underset{⬝\,⬝}{:\mathrm P:}}\;\right]}^{\color[rgb]{0.0, 0.0, 1.0}{3-}}\)

\({\color[rgb]{0.8, 0.0, 0.0}\begin{array}{c}\mathrm K^+\\\mathrm K^+\\\mathrm K^+\end{array}}\;+\;{\color[rgb]{0.0, 0.0, 1.0}\left[\overset{⬝\,⬝}{\underset{⬝\,⬝}{:\mathrm P:}}\;\right]}^{\color[rgb]{0.0, 0.0, 1.0}{3-}}\;\Rightarrow\;\mathrm K_3^+\mathrm P^{3-}\;\Rightarrow\;{\mathrm K}_3\mathrm P\)

Summary

- The tendency to form species that have eight electrons in the valence shell is called the octet rule.

- The attraction of oppositely charged ions caused by electron transfer is called an ionic bond.

This page is shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Marisa Alviar-Agnew, Henry Agnew and Lance S. Lund (Anoka-Ramsey Community College).