11.2: Representing Valence Electrons with Dots

- Page ID

- 289424

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)⚙️ Learning Objective

- Draw a Lewis electron dot diagram for an atom.

In almost all cases, chemical bonds are formed by interactions of valence electrons in atoms. To facilitate our understanding of how valence electrons interact, a simple method for representing those valence electrons would be useful.

A Lewis electron dot diagram (or electron dot diagram, Lewis dot diagram, Lewis diagram, or Lewis structure) is a representation of the valence electrons of an atom that uses dots that surround the chemical symbol of the element. The number of dots equals the number of valence electrons in the atom. Dots are arranged to the right, left, above, and below the symbol, with no more than two dots on any one side. For example, the Lewis dot diagram for hydrogen is simply

\(\mathrm H\;⋅\)

The side on which the dot is placed is not important, so the Lewis diagram for hydrogen may be drawn as:

\(\mathrm H\,⋅\) or \(\overset⬝{\mathrm H}\) or \(⋅\,\mathrm H\) or \(\underset⬝{\mathrm H}\)

As electrons are added around the chemical symbol, the general convention for dot placement is that one dot is placed on each side before doubling up, though helium is a notable exception. The Lewis diagram for helium, with its two valence electrons, is:

\(\mathrm{He:}\)

Again, the side on which the dots are placed is not important, so the Lewis diagram for helium may be drawn as:

\(\mathrm{He:}\) or \(\overset{⬝\,⬝}{\mathrm {He}}\) or \(\mathrm{:He}\) or \(\underset{⬝\,⬝}{\mathrm {He}}\)

Placing the two dots together on the same side represents two electrons that are paired up. It turns out that the first energy level of an atom holds a maximum of two electrons. Since helium atoms only have two electrons and the outermost energy level is the first energy level, the two electrons have no other option but to be paired up. When the outermost energy level is any other level beyond the first energy level, it may contain up to eight valence electrons. In other words, the maximum number of valence electrons that an atom may have is eight, which is why we represent the Lewis diagrams of the elements with four sides that may show up to two dots on each side.

Since the number of valence electrons for a main group element is equal to the Roman numeral, the generic Lewis diagrams for each group are:

Group |

IA | IIA | IIIA | IVA | VA | VIA | VIIA | VIIIA |

Valence Electrons |

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8* |

Lewis Diagram |

\(\mathrm X\,⋅\) | \(⋅\,\mathrm{X}\,⋅\) | \(\overset⬝{\underset⬝{\mathrm{X}}}\,⋅\) | \(\overset⬝{\underset⬝{⋅\,\mathrm{X}\,⋅}}\) |

\(\overset⬝{\underset⬝{:\mathrm{X}\,⋅}}\) |

\(\overset⬝{\underset{⬝\,⬝}{:\mathrm{X}\,⋅}}\) | \(\overset{⬝\,⬝}{\underset{⬝\,⬝}{:\mathrm{X}\,⋅}}\) | \(\overset{⬝\,⬝}{\underset{⬝\,⬝}{:\mathrm{X}:}}\) |

| *Helium is an exception and has just two valence electrons (see above). | ||||||||

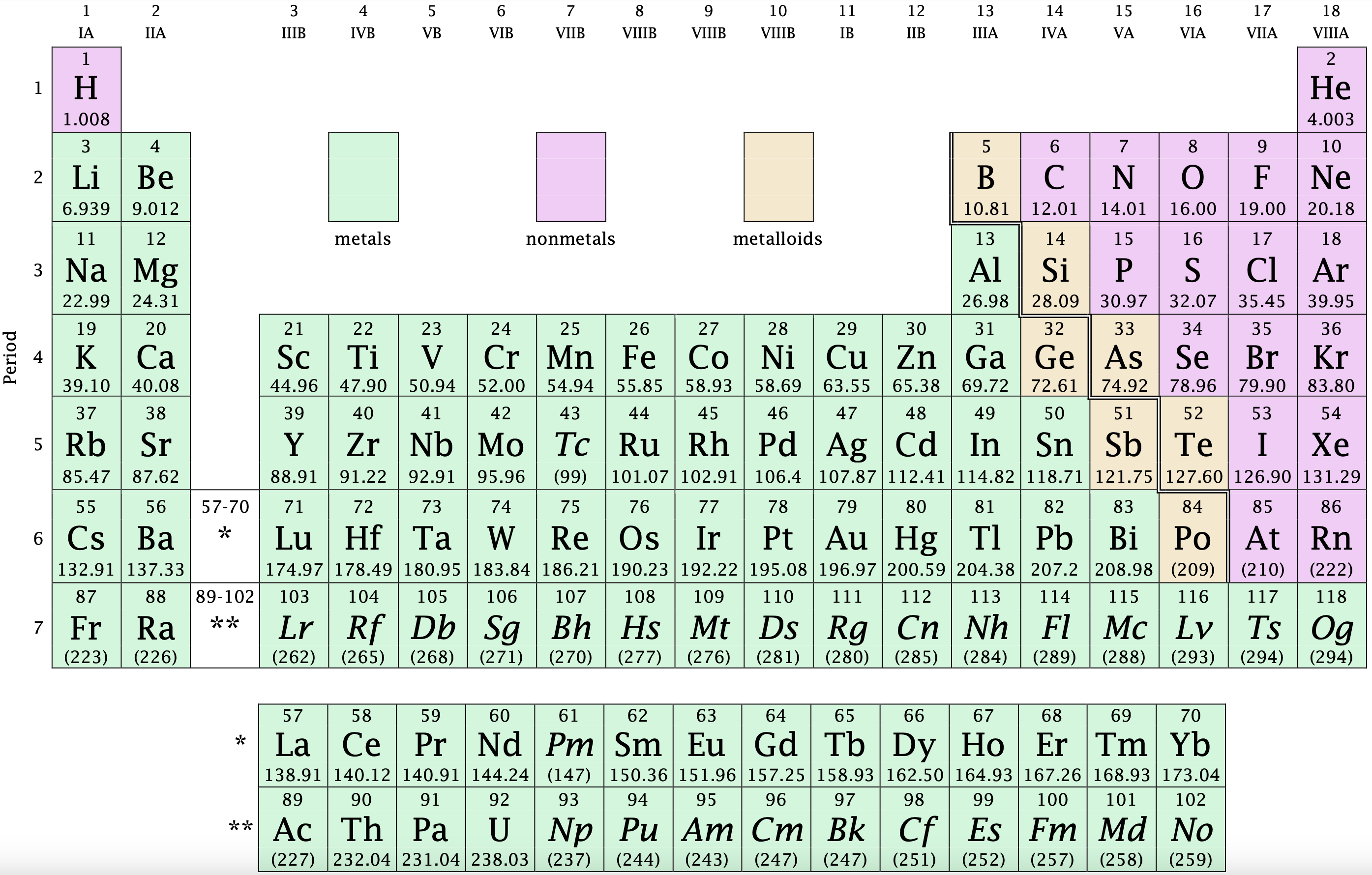

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Use this periodic table for the examples and exercises below. An interactive periodic table may be found here.

✅ Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Lewis Dot Diagrams

Write the Lewis diagram for each element.

- sulfur

- helium

- potassium

- aluminum

Solution

- Sulfur (S) is located in Group VIA, so it has 6 valence electrons.

\(\overset⬝{\underset{⬝\,⬝}{:\mathrm{S}\,⋅}}\)

- Helium (He) atoms have two electrons and is the only exception for the main group elements in terms of valence electrons.

\(\mathrm{He:}\)

- Potassium (K) is located in Group IA, so it has 1 valence electron.

\(\mathrm K\,⋅\)

- Aluminum (Al) is located in Group IIIA (Group 13), so it has 3 valence electrons.

\(\overset⬝{\underset⬝{\mathrm{Al}}}\,⋅\)

✏️ Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Write the Lewis diagram for each element.

- phosphorus

- argon

- silicon

- magnesium

- Answer A

-

\(\overset⬝{\underset⬝{:\mathrm{P}\,⋅}}\)

- Answer B

-

\(\overset{⬝\,⬝}{\underset{⬝\,⬝}{:\mathrm{Ar}:}}\)

- Answer C

-

\(\overset⬝{\underset⬝{⋅\,\mathrm{Si}\,⋅}}\)

- Answer D

-

\(⋅\,\mathrm{Mg}\,⋅\)

Summary

- Lewis electron dot diagrams use dots to represent valence electrons around an atomic symbol.

This page is shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Marisa Alviar-Agnew, Henry Agnew and Lance S. Lund (Anoka-Ramsey Community College).