15.7: Oxidation of Alcohols

- Page ID

- 22005

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

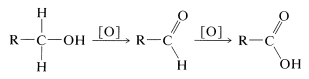

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)According to the scale of oxidation levels established for carbon (see Table 11-1), primary alcohols \(\left( \ce{RCH_2OH} \right)\) are at a lower oxidation level than either aldehydes \(\left( \ce{RCHO} \right)\) or carboxylic acids \(\left( \ce{RCO_2H} \right)\). With suitable oxidizing agents, primary alcohols in fact can be oxidized first to aldehydes and then to carboxylic acids.

primary alcohols

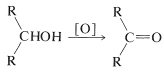

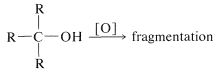

Unlike the reactions discussed previously in this chapter, oxidation of alcohols involves the alkyl portion of the molecule, or more specifically, the \(\ce{C-H}\) bonds of the hydroxyl-bearing carbon (the \(\alpha\) carbon). Secondary alcohols, which have only one such \(\ce{C-H}\) bond, are oxidized to ketones, whereas tertiary alcohols, which have no \(\ce{C-H}\) bonds to the hydroxylic carbon, are oxidized only with accompanying degradation into smaller fragments by cleavage of carbon-carbon bonds.

secondary alcohols

tertiary alcohols

Industrial Oxidation of Alcohols

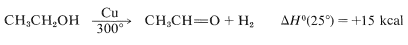

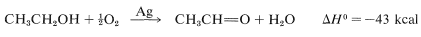

Conversion of ethanol to ethanal is carried out on a commercial scale by passing gaseous ethanol over a copper catalyst at \(300^\text{o}\):

At room temperature this reaction is endothermic with an equilibrium constant of about \(10^{22}\). At \(300^\text{o}\) conversions of \(20\%\)-\(50\%\) per pass can be realized and, by recycling the unreacted alcohol, the yield can be greater than \(90\%\).

Another commercial process uses a silver catalyst and oxygen to combine with the hydrogen, which makes the net reaction substantially exothermic:

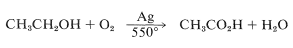

In effect, this is a partial combustion reaction and requires very careful control to prevent overoxidation. In fact, by modifying the reaction conditions (alcohol-to-oxygen ratio, temperature, pressure, and reaction time), the oxidation proceeds smoothly to ethanoic acid:

Reactions of this type are particularly suitable as industrial processes because they generally can be run in continuous-flow reactors, and can utilize a cheap oxidizing agent, usually supplied directly as air.

Oxidation of Alcohols

Chromic Acid Oxidation

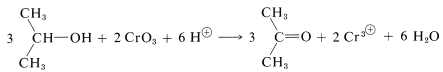

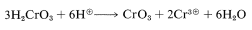

Laboratory oxidation of alcohols most often is carried out with chromic acid \(\left( \ce{H_2CrO_4} \right)\), which usually is prepared as required from chromic oxide \(\left( \ce{CrO_3} \right)\) or from sodium dichromate \(\left( \ce{Na_2Cr_2O_7} \right)\) in combination with sulfuric acid. Ethanoic (acetic) acid is a useful solvent for such reactions:

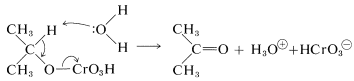

The mechanism of the chromic acid oxidation of 2-propanol to 2-propanone (acetone) has been investigated very thoroughly. It is a highly interesting reaction in that it reveals how changes of oxidation state can occur in a reaction involving a typical inorganic and a typical organic compound. The initial step is reversible formation of an isopropyl ester of chromic acid. This ester is unstable and is not isolated:

The subsequent step is the slowest in the sequence and appears to involve attack of a base (water) at the alpha hydrogen of the chromate ester concurrent with elimination of the \(\ce{HCrO_3^-}\) group. There is an obvious analogy between this step and an \(E2\) reaction (Section 8-8A):

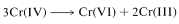

The transformation of chromic acid \(\left( \ce{H_2CrO_4} \right)\) to \(\ce{H_2CrO_3}\) amounts to the reduction of chromium from an oxidation state of \(+6\) to \(+4\). Disproportionation of Cr(IV) occurs rapidly to give compounds of Cr(III) and Cr(VI):

or

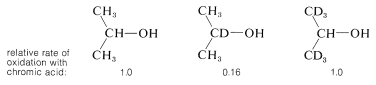

The \(E2\) character of the ketone-forming step has been demonstrated in two ways. First, the rate of decomposition of isopropyl hydrogen chromate to 2-propanone and \(\ce{H_2CrO_3}\) is strongly accelerated by efficient proton-removing substances. Second, the hydrogen on the \(\alpha\) carbon clearly is removed in a slow reaction because the overall oxidation rate is diminished sevenfold by having a deuterium in place of the \(\alpha\) hydrogen. No significant slowing of oxidation is noted for 2-propanol having deuterium in the methyl groups:

Carbon-deuterium bonds normally are broken more slowly than carbon-hydrogen bonds. This so-called kinetic isotope effect provides a general method for determining whether particular carbon-hydrogen bonds are broken in slow reaction steps.

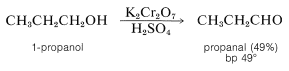

Primary alcohols are oxidized by chromic acid in sulfuric acid solution to aldehydes, but to stop the reaction at the aldehyde stage, it usually is necessary to remove the aldehyde from the reaction mixture as it forms. This can be done by distillation if the aldehyde is reasonably volatile:

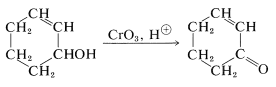

Unsaturated alcohols can be oxidized to unsaturated ketones by chromic acid, because chromic acid usually attacks double bonds relatively slowly:

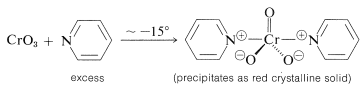

However, complications are to be expected when the double bond of an unsaturated alcohol is particularly reactive or when the alcohol rearranges readily under strongly acidic conditions. It is possible to avoid the use of strong acid through the combination of chromic oxide with the weak base azabenzene (pyridine). A crystalline solid of composition \(\ce{(C_5H_5N)_2} \cdot \ce{CrO_3}\) is formed when \(\ce{CrO_3}\) is added to excess pyridine at low temperatures. (Addition of pyridine to \(\ce{CrO_3}\) is likely to give an uncontrollable reaction resulting in a fire.)

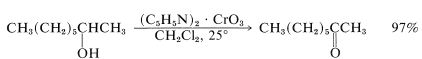

The pyridine-\(\ce{CrO_3}\) reagent is soluble in chlorinated solvents such as dichloromethane, and the resulting solutions rapidly oxidize  to

to  at ordinary temperatures:

at ordinary temperatures:

The yields usually are good, partly because the absence of strong acid minimizes degradation and rearrangement, and partly because the product can be isolated easily. The inorganic products are insoluble and can be separated by filtration, thereby leaving the oxidized product in dichloromethane from which it can be easily recovered.

Permanganate Oxidation

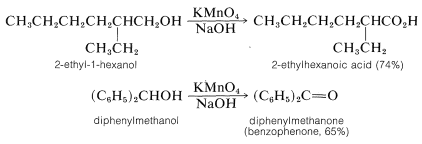

Permanganate ion, \(\ce{MnO_4^-}\), oxidizes both primary and secondary alcohols in either basic or acidic solution. With primary alcohols the product normally is the carboxylic acid because the intermediate aldehyde is oxidized rapidly by permanganate:

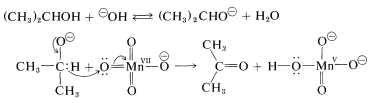

Oxidation under basic conditions evidently involves the alkoxide ion rather than the neutral alcohol. The oxidizing agent, \(\ce{MnO_4^-}\), abstracts the alpha hydrogen from the alkoxide ion either as an atom (one-electron transfer) or as hydride, \(\ce{H}^\ominus\) (two-electron transfer). The steps for the two-electron sequence are:

In the second step, permanganate ion is reduced from Mn(VII) to Mn(V). However, the stable oxidation states of manganese are \(+2\), \(+4\), and \(+7\); thus the Mn(V) ion formed disproportionates to Mn(VII) and Mn(IV). The normal manganese end product from oxidations in basic solution is manganese dioxide, \(\ce{MnO_2}\), in which \(\ce{Mn}\) has an oxidation state of \(+4\) corresponding to Mn(IV).

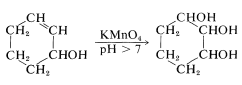

In Section 11-7C we described the use of permanganate for the oxidation of alkenes to 1,2-diols. How is it possible to control this reaction so that it will stop at the diol stage when permanganate also can oxidize  to

to  ? Overoxidation with permanganate is always a problem, but the relative reaction rates are very much a function of the pH of the reaction mixture and, in basic solution, potassium permanganate oxidizes unsaturated groups more rapidly than it oxidizes alcohols:

? Overoxidation with permanganate is always a problem, but the relative reaction rates are very much a function of the pH of the reaction mixture and, in basic solution, potassium permanganate oxidizes unsaturated groups more rapidly than it oxidizes alcohols:

Biological Oxidations

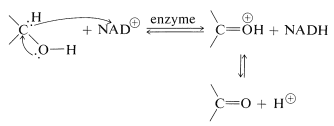

There are many biological oxidations that convert a primary or secondary alcohol to a carbonyl compound. These reactions cannot possibly involve the extreme pH conditions and vigorous inorganic oxidants used in typical laboratory oxidations. Rather, they occur at nearly neutral pH values and they all require enzymes as catalysts, which for these reactions usually are called dehydrogenases.

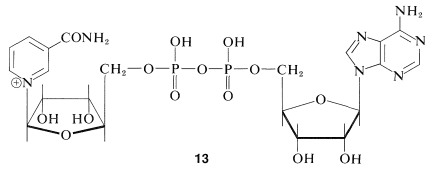

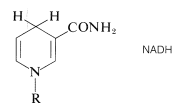

An important group of biological oxidizing agents includes the pyridine nucleotides, of which nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (\(\ce{NAD}^\oplus\), \(13\)) is an example:

This very complex molecule functions to accept hydride \(\left( \ce{H}^\ominus \right)\) or the equivalent \(\left( \ce{H}^\oplus + 2 \ce{e^-} \right)\) from the \(\alpha\) carbon of an alcohol:

The reduced form of \(\ce{NAD}^\oplus\) is abbreviated as \(\ce{NADH}\) and the \(\ce{H}^\ominus\) is added at the 4-position of the pyridine ring:

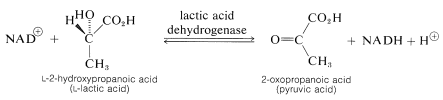

Some examples follow that illustrate the remarkable specificity of this kind of redox system. One of the last steps in the metabolic breakdown of glucose (glycolysis; Section 20-10A) is the reduction of 2-oxopropanoic (pyruvic) acid to \(L\)-2-hydroxypropanoic (lactic) acid. The reverse process is oxidation of \(L\)-lactic acid. The enzyme lactic acid dehydrogenase catalyses this reaction, and it functions only with the \(L\)-enantiomer of lactic acid:

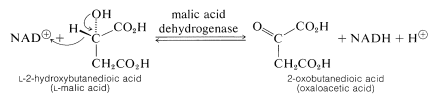

A second example, provided by one of the steps in metabolism by way of the Krebs citric acid cycle (see Section 20-10B), is the oxidation of \(L\)-2-hydroxy-butanedioic (\(L\)-malic) acid to 2-oxobutanedioic (oxaloacetic) acid. This enzyme functions only with \(L\)-malic acid:

All of these reactions release energy. In biological oxidations much of the energy is utilized to form ATP from ADP and inorganic phosphate (Section 15-5F). That is to say, electron-transfer reactions are coupled with ATP formation. The overall process is called oxidative phosphorylation.

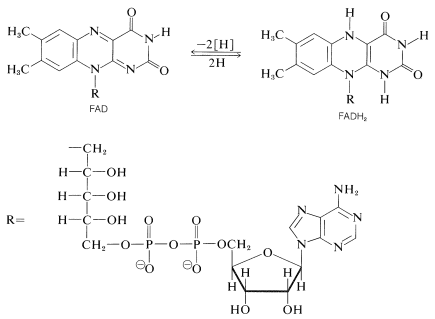

Another important oxidizing agent in biological systems is flavin adenine dinucleotide, \(\ce{FAD}\). Like \(\ce{NAD}^\oplus\), it is a two-electron acceptor, but unlike \(\ce{NAD}^\oplus\), it accepts two electrons as \(2 \ce{H} \cdot\) rather than as \(\ce{H}^\ominus\). The reduced form, \(\ce{FADH_2}\), has the hydrogens at ring nitrogens:

Contributors

John D. Robert and Marjorie C. Caserio (1977) Basic Principles of Organic Chemistry, second edition. W. A. Benjamin, Inc. , Menlo Park, CA. ISBN 0-8053-8329-8. This content is copyrighted under the following conditions, "You are granted permission for individual, educational, research and non-commercial reproduction, distribution, display and performance of this work in any format."