3.3: Formulas for Ionic Compounds

- Page ID

- 16137

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Write the chemical formula for a simple ionic compound.

- Recognize polyatomic ions in chemical formulas.

We have already encountered some chemical formulas for simple ionic compounds. A chemical formula is a concise list of the elements in a compound and the ratios of these elements. To better understand what a chemical formula means, we must consider how an ionic compound is constructed from its ions.

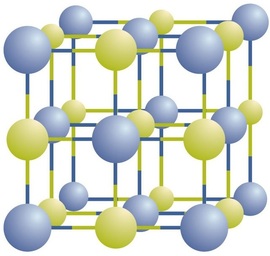

Ionic compounds exist as alternating positive and negative ions in regular, three-dimensional arrays called crystals (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). As you can see, there are no individual \(\ce{NaCl}\) “particles” in the array; instead, there is a continuous lattice of alternating sodium and chloride ions. However, we can use the ratio of sodium ions to chloride ions, expressed in the lowest possible whole numbers, as a way of describing the compound. In the case of sodium chloride, the ratio of sodium ions to chloride ions, expressed in lowest whole numbers, is 1:1, so we use \(\ce{NaCl}\) (one \(\ce{Na}\) symbol and one \(\ce{Cl}\) symbol) to represent the compound. Thus, \(\ce{NaCl}\) is the chemical formula for sodium chloride, which is a concise way of describing the relative number of different ions in the compound. A macroscopic sample is composed of myriads of NaCl pairs; each individual pair called a formula unit. Although it is convenient to think that \(\ce{NaCl}\) crystals are composed of individual \(\ce{NaCl}\) units, Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) shows that no single ion is exclusively associated with any other single ion. Each ion is surrounded by ions of opposite charge.

The formula for an ionic compound follows several conventions. First, the cation is written before the anion. Because most metals form cations and most nonmetals form anions, formulas typically list the metal first and then the nonmetal. Second, charges are not written in a formula. Remember that in an ionic compound, the component species are ions, not neutral atoms, even though the formula does not contain charges. Finally, the proper formula for an ionic compound always has a net zero charge, meaning the total positive charge must equal the total negative charge. To determine the proper formula of any combination of ions, determine how many of each ion is needed to balance the total positive and negative charges in the compound.

This rule is ultimately based on the fact that matter is, overall, electrically neutral.

By convention, assume that there is only one atom if a subscript is not present. We do not use 1 as a subscript.

If we look at the ionic compound consisting of lithium ions and bromide ions, we see that the lithium ion has a 1+ charge and the bromide ion has a 1− charge. Only one ion of each is needed to balance these charges. The formula for lithium bromide is \(\ce{LiBr}\).

When an ionic compound is formed from magnesium and oxygen, the magnesium ion has a 2+ charge, and the oxygen atom has a 2− charge. Although both of these ions have higher charges than the ions in lithium bromide, they still balance each other in a one-to-one ratio. Therefore, the proper formula for this ionic compound is \(\ce{MgO}\).

Now consider the ionic compound formed by magnesium and chlorine. A magnesium ion has a 2+ charge, while a chlorine ion has a 1− charge:

\[\ce{Mg^{2+}Cl^{−}} \nonumber \]

Combining one ion of each does not completely balance the positive and negative charges. The easiest way to balance these charges is to assume the presence of two chloride ions for each magnesium ion:

\[\ce{Mg^{2+} Cl^{−} Cl^{−}} \nonumber \]

Now the positive and negative charges are balanced. We could write the chemical formula for this ionic compound as \(\ce{MgClCl}\), but the convention is to use a numerical subscript when there is more than one ion of a given type—\(\ce{MgCl2}\). This chemical formula says that there are one magnesium ion and two chloride ions in this formula. (Do not read the “Cl2” part of the formula as a molecule of the diatomic elemental chlorine. Chlorine does not exist as a diatomic element in this compound. Rather, it exists as two individual chloride ions.) By convention, the lowest whole number ratio is used in the formulas of ionic compounds. The formula \(\ce{Mg2Cl4}\) has balanced charges with the ions in a 1:2 ratio, but it is not the lowest whole number ratio.

By convention, the lowest whole-number ratio of the ions is used in ionic formulas. There are exceptions for certain ions, such as \(\ce{Hg2^{2+}}\).

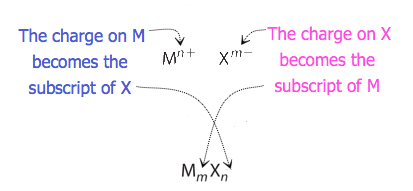

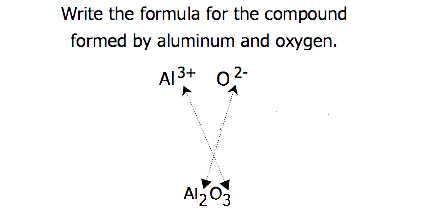

For compounds in which the ratio of ions is not as obvious, the subscripts in the formula can be obtained by crossing charges: use the absolute value of the charge on one ion as the subscript for the other ion. This method is shown schematically in Figure 3.3.2.

When crossing charges, it is sometimes necessary to reduce the subscripts to their simplest ratio to write the empirical formula. Consider, for example, the compound formed by Pb4+ and O2−. Using the absolute values of the charges on the ions as subscripts gives the formula Pb2O4. This simplifies to its correct empirical formula PbO2. The empirical formula has one Pb4+ ion and two O2− ions.

Write the chemical formula for an ionic compound composed of each pair of ions.

- the sodium ion and the sulfur ion

- the aluminum ion and the fluoride ion

- the 3+ iron ion and the oxygen ion

Solution

- To obtain a valence shell octet, sodium forms an ion with a 1+ charge, while the sulfur ion has a 2− charge. Two sodium 1+ ions are needed to balance the 2− charge on the sulfur ion. Rather than writing the formula as \(\ce{NaNaS}\), we shorten it by convention to \(\ce{Na2S}\).

- The aluminum ion has a 3+ charge, while the fluoride ion formed by fluorine has a 1− charge. Three fluorine 1− ions are needed to balance the 3+ charge on the aluminum ion. This combination is written as \(\ce{AlF3}\).

- Iron can form two possible ions, but the ion with a 3+ charge is specified here. The oxygen atom has a 2− charge as an ion. To balance the positive and negative charges, we look to the least common multiple—6: two iron 3+ ions will give 6+, while three 2− oxygen ions will give 6−, thereby balancing the overall positive and negative charges. Thus, the formula for this ionic compound is \(\ce{Fe2O3}\). Alternatively, use the crossing charges method shown in Figure 3.3.2.

Write the chemical formula for an ionic compound composed of each pair of ions.

- the calcium ion and the oxygen ion

- the 2+ copper ion and the sulfur ion

- the 1+ copper ion and the sulfur ion

- Answer a:

-

CaO

- Answer b:

-

CuS

- Answer c:

-

Cu2S

Polyatomic Ions

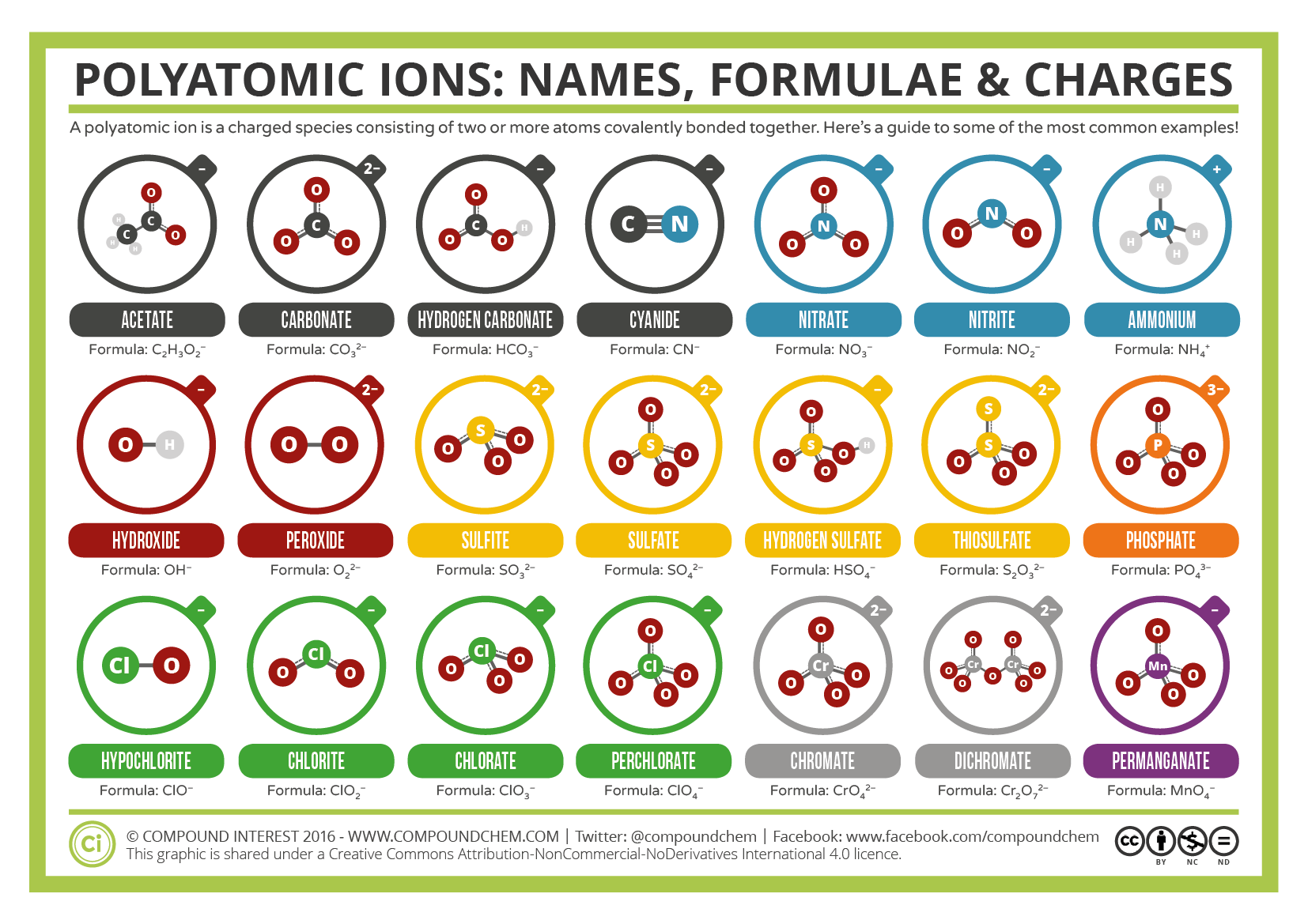

Some ions consist of groups of atoms covalently bonded together and have an overall electric charge. Because these ions contain more than one atom, they are called polyatomic ions. The Lewis structures, names and formulas of some polyatomic ions are found in Table 3.3.1.

Table \(\PageIndex{1}\): Some Polyatomic Ions

Polyatomic ions have defined formulas, names, and charges that cannot be modified in any way. Table \(\PageIndex{2}\) lists the ion names and ion formulas of the most common polyatomic ions. For example, \(\ce{NO3^{−}}\) is the nitrate ion; it has one nitrogen atom and three oxygen atoms and an overall 1− charge. Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) lists the most common polyatomic ions.

| Ion Name | Ion Formula |

|---|---|

| ammonium ion | NH4+1 |

| hydroxide ion | OH−1 |

| cyanide ion | CN−1 |

| carbonate ion | CO3−2 |

| bicarbonate or hydrogen carbonate | HCO3− |

| acetate ion | C2H3O2−1 or CH3CO2−1 |

| nitrate ion | NO3−1 |

| nitrite ion | NO2−1 |

| sulfate ion | SO4−2 |

| sulfite ion | SO3−2 |

| phosphate ion | PO4−3 |

| phosphite ion | PO3−3 |

Note that only one polyatomic ion in this Table, the ammonium ion (NH4+1), is a cation. This polyatomic ion contains one nitrogen and four hydrogens that collectively bear a +1 charge. The remaining polyatomic ions are all negatively-charged and, therefore, are classified as anions. However, only two of these, the hydroxide ion and the cyanide ion, are named using the "-ide" suffix that is typically indicative of negatively-charged particles. The remaining polyatomic anions, which all contain oxygen, in combination with another non-metal, exist as part of a series in which the number of oxygens within the polyatomic unit can vary. As has been repeatedly emphasized in several sections of this text, no two chemical formulas should share a common chemical name. A single suffix, "-ide," is insufficient for distinguishing the names of the anions in a related polyatomic series. Therefore, "-ate" and "-ite" suffixes are employed, in order to denote that the corresponding polyatomic ions are part of a series. Additionally, these suffixes also indicate the relative number of oxygens that are contained within the polyatomic ions. Note that all of the polyatomic ions whose names end in "-ate" contain one more oxygen than those polyatomic anions whose names end in "-ite." Unfortunately, much like the common system for naming transition metals, these suffixes only indicate the relative number of oxygens that are contained within the polyatomic ions. For example, the nitrate ion, which is symbolized as NO3−1, has one more oxygen than the nitrite ion, which is symbolized as NO2−1. However, the sulfate ion is symbolized as SO4−2. While both the nitrate ion and the sulfate ion share an "-ate" suffix, the former contains three oxygens, but the latter contains four. Additionally, both the nitrate ion and the sulfite ion contain three oxygens, but these polyatomic ions do not share a common suffix. Unfortunately, the relative nature of these suffixes mandates that the ion formula/ion name combinations of the polyatomic ions must simply be memorized.

The rule for constructing formulas for ionic compounds containing polyatomic ions is the same as for formulas containing monatomic (single-atom) ions: the positive and negative charges must balance. If more than one of a particular polyatomic ion is needed to balance the charge, the entire formula for the polyatomic ion must be enclosed in parentheses, and the numerical subscript is placed outside the parentheses. This is to show that the subscript applies to the entire polyatomic ion. Two examples are shown below:

Write the chemical formula for an ionic compound composed of each pair of ions.

- the potassium ion and the sulfate ion

- the calcium ion and the nitrate ion

Solution

- Potassium ions have a charge of 1+, while sulfate ions have a charge of 2−. We will need two potassium ions to balance the charge on the sulfate ion, so the proper chemical formula is \(\ce{K_2SO_4}\).

- Calcium ions have a charge of 2+, while nitrate ions have a charge of 1−. We will need two nitrate ions to balance the charge on each calcium ion. The formula for nitrate must be enclosed in parentheses. Thus, we write \(\ce{Ca(NO3)2}\) as the formula for this ionic compound.

Write the chemical formula for an ionic compound composed of each pair of ions.

- the magnesium ion and the carbonate ion

- the aluminum ion and the acetate ion

- Answer a:

-

Mg2+ and CO32- = MgCO3

- Answer b:

-

Al3+ and C2H3O2- = Al(C2H3O2)3

Recognizing Ionic Compounds

There are two ways to recognize ionic compounds. First, compounds between metal and nonmetal elements are usually ionic. For example, CaBr2 contains a metallic element (calcium, a group 2A metal) and a nonmetallic element (bromine, a group 7A nonmetal). Therefore, it is most likely an ionic compound. (In fact, it is ionic.) In contrast, the compound NO2 contains two elements that are both nonmetals (nitrogen, from group 5A, and oxygen, from group 6A). It is not an ionic compound; it belongs to the category of covalent compounds discuss elsewhere. Also note that this combination of nitrogen and oxygen has no electric charge specified, so it is not the nitrite ion.

Second, if you recognize the formula of a polyatomic ion in a compound, the compound is ionic. For example, if you see the formula \(\ce{Ba(NO3)2}\), you may recognize the “NO3” part as the nitrate ion, \(\rm{NO_3^−}\). (Remember that the convention for writing formulas for ionic compounds is not to include the ionic charge.) This is a clue that the other part of the formula, \(\ce{Ba}\), is actually the \(\ce{Ba^{2+}}\) ion, with the 2+ charge balancing the overall 2− charge from the two nitrate ions. Thus, this compound is also ionic.

Identify each compound as ionic or not ionic.

- \(\ce{Na2O}\)

- \(\ce{PCl3}\)

- \(\ce{NH4Cl}\)

- \(\ce{OF2}\)

Solution

- Sodium is a metal, and oxygen is a nonmetal; therefore, \(\ce{Na2O}\) is expected to be ionic.

- Both phosphorus and chlorine are nonmetals. Therefore, \(\ce{PCl3}\) is not ionic.

- The \(\ce{NH4}\) in the formula represents the ammonium ion, \(\ce{NH4^{+}}\), which indicates that this compound is ionic.

- Both oxygen and fluorine are nonmetals. Therefore, \(\ce{OF2}\) is not ionic.

Identify each compound as ionic or not ionic.

- \(\ce{N2O}\)

- \(\ce{FeCl3}\)

- \(\ce{(NH4)3PO4}\)

- \(\ce{SOCl2}\)

- Answer a:

-

not ionic

- Answer b:

-

ionic

- Answer c:

-

ionic

- Answer d:

-

not ionic

Science has long recognized that blood and seawater have similar compositions. After all, both liquids have ionic compounds dissolved in them. The similarity may be more than mere coincidence; many scientists think that the first forms of life on Earth arose in the oceans. A closer look, however, shows that blood and seawater are quite different. A 0.9% solution of sodium chloride approximates the salt concentration found in blood. In contrast, seawater is principally a 3% sodium chloride solution, over three times the concentration in blood. Here is a comparison of the amounts of ions in blood and seawater:

| Ion | Percent in Seawater | Percent in Blood |

|---|---|---|

| Na+ | 2.36 | 0.322 |

| Cl− | 1.94 | 0.366 |

| Mg2+ | 0.13 | 0.002 |

| SO42− | 0.09 | — |

| K+ | 0.04 | 0.016 |

| Ca2+ | 0.04 | 0.0096 |

| HCO3− | 0.002 | 0.165 |

| HPO42−, H2PO4− | — | 0.01 |

Most ions are more abundant in seawater than they are in blood, with some important exceptions. There are far more hydrogen carbonate ions (\(\ce{HCO3^{−}}\)) in blood than in seawater. This difference is significant because the hydrogen carbonate ion and some related ions have a crucial role in controlling the acid-base properties of blood. The amount of hydrogen phosphate ions—\(\ce{HPO4^{2−}}\) and \(\ce{H2PO4^{−}}\)—in seawater is very low, but they are present in higher amounts in blood, where they also affect acid-base properties. Another notable difference is that blood does not have significant amounts of the sulfate ion (\(\ce{SO4^{2−}}\)), but this ion is present in seawater.

Key Takeaways

- Proper chemical formulas for ionic compounds balance the total positive charge with the total negative charge.

- Groups of atoms with an overall charge, called polyatomic ions, also exist.

EXERCISES

- What information is contained in the formula of an ionic compound?

- Why do the chemical formulas for some ionic compounds contain subscripts, while others do not?

3. Write the chemical formula for the ionic compound formed by each pair of ions.

- Mg2+ and I−

- Na+ and O2−

4. Write the chemical formula for the ionic compound formed by each pair of ions.

- Na+ and Br−

- Mg2+ and Br−

- Mg2+ and S2−

5. Write the chemical formula for the ionic compound formed by each pair of ions.

- K+ and Cl−

- Mg2+ and Cl−

- Mg2+ and Se2−

6. Write the chemical formula for the ionic compound formed by each pair of ions.

- Na+ and N3−

- Mg2+ and N3−

- Al3+ and S2−

7. Write the chemical formula for the ionic compound formed by each pair of ions.

- Li+ and N3−

- Mg2+ and P3−

- Li+ and P3−

8. Write the chemical formula for the ionic compound formed by each pair of ions.

- Fe3+ and Br−

- Fe2+ and Br−

- Au3+ and S2−

- Au+ and S2−

9. Write the chemical formula for the ionic compound formed by each pair of ions.

- Cr3+ and O2−

- Cr2+ and O2−

- Pb2+ and Cl−

- Pb4+ and Cl−

10. Write the chemical formula for the ionic compound formed by each pair of ions.

- Cr3+ and NO3−

- Fe2+ and PO43−

- Ca2+ and CrO42−

- Al3+ and OH−

11. Write the chemical formula for the ionic compound formed by each pair of ions.

- NH4+ and NO3−

- H+ and Cr2O72−

- Cu+ and CO32−

- Na+ and HCO3−

12. For each pair of elements, determine the charge for their ions and write the proper formula for the resulting ionic compound between them.

- Ba and S

- Cs and I

13. For each pair of elements, determine the charge for their ions and write the proper formula for the resulting ionic compound between them.

- K and S

- Sc and Br

14. Which compounds would you predict to be ionic?

- Li2O

- (NH4)2O

- CO2

- FeSO3

- C6H6

- C2H6O

15. Which compounds would you predict to be ionic?

- Ba(OH)2

- CH2O

- NH2CONH2

- (NH4)2CrO4

- C8H18

- NH3

Answers

1. the ratio of each kind of ion in the compound

2. Sometimes more than one ion is needed to balance the charge on the other ion in an ionic compound.

3.

- MgI2

- Na2O

4.

- NaBr

- MgBr2

- MgS

5.

- KCl

- MgCl2

- MgSe

6.

- Na3N

- Mg3N2

- Al2S3

7.

- Li3N

- Mg3P2

- Li3P

8.

- FeBr3

- FeBr2

- Au2S3

- Au2S

9.

- Cr2O3

- CrO

- PbCl2

- PbCl4

10.

- Cr(NO3)3

- Fe3(PO4)2

- CaCrO4

- Al(OH)3

11.

- NH4NO3

- H2Cr2O7

- Cu2CO3

- NaHCO3

12.

- Ba2+, S2−, BaS

- Cs+, I−, CsI

13.

- K+, S2−, K2S

- Sc3+, Br−, ScBr3

14.

- ionic

- ionic

- not ionic

- ionic

- not ionic

- not ionic

15.

- ionic

- not ionic

- not ionic

- ionic

- not ionic

- not ionic