1.10: Ionization Energies and Electron Affinities

- Page ID

- 2538

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Example of IE1 of Magnesium: Mg(g) -> Mg+(g) + e- I1 = 738 kJ/mol

IE1 stands for the first ionization energy: the energy the atom requires to expel the first electron from its orbital. Similarly, the second ionization energy, will be the energy needed to expel the second electron.

Mg+(g) -> Mg2+(g) + e- I2 = 1,451 kJ/mol

However, IE2 of Magnesium will be larger than that of IE1 because it is not energetically favorable to separate an electron from a positively charged ion.

The general pattern of the ionization energy as they are in regard to the period table is that the IE increases across a period, and decreases down a group. Because it requires more energy to remove an electron from a stable atom, the noble gases are usually associated with the highest IE1. Because their valence shells are already filled and stablized, they will require much more energy to disrupt that stability. The first electron that is expelled is the most loosely held to the atom.

On the other hand, the group 1 elements are usually associated with the lowest IE1. Since only one electron occupies the valence shell of these atoms, it will be more energetically favorable for them to lose the electron in order to achieve a full orbital shell.

However, there are few exceptions. The IE1 decreases when crossing from element in group 15 to the element in group 16. The group 15 has half-filled electronic configuration ns2 np3. This type of configuration is very stable; it’s hard to remove electron from valence shell. Therefore, element in group 15 requires greater value of IE1 than group 16. Another exception is that going from Be (group 2) to B (group 13), the IE1 decreases because Be has the filled shell 2s2 which is more stable than the electronic configuration of B 2s2 2p1. Hence, Be will require more IE1 than B. Similarly, the IE1 decreases when going from elements in group 12 to group 13

Electron Affinities

Electron affinity, often abbreviated as EA, is the energy released when an electron is added to a valence shell of the atom.

F(g) + e- -> F-(g) EA = -328 kJ/mol

[When an electron is added to an atom, energy is given off. This process is exothermic. ]

Atoms like the noble gases will not gain an electron because they are already in their most stable state with a full shell. Atoms like F will most likely gain an electron because when a free electron is added to the outer shell of fluorine, it will have obtained a full shell. Generally, atoms increasing across a period will increase in EA also.

Exothermic vs endothermic process

O(g) + e- -> O-(g) EA1= -141.0 kJ/mol

O-(g) + e- -> O2-(g) EA2 = +744kJ/mol

When an electron is added to an atom, the energy change is exothermic because of the attraction of the electron to the nucleus. However, in the case of EA2 where the electron is added to an anion, the repulsion between the anion and this newly added electron will overwhelm the attraction of the electron to the nucleus. Therefore, this process will be endothermic, as opposed to EA1.

Periodic Trend

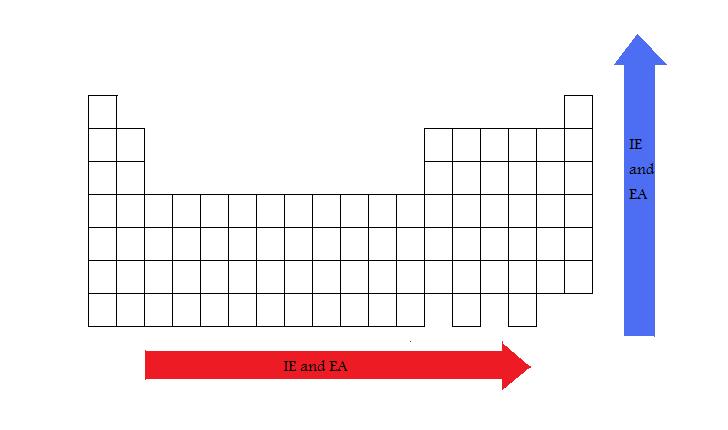

The general trend of IE and EA along a periodic table.

References

- Vedeneyer, Vladimir Ivanovich. Bond Energies Ionization Potentials and Electron Affinities. London: Edward Arnold, 1966. Print.

- Petrucci, Ralph. General Chemistry: Principles and Modern Applications. New Jersey. Pearson Prentice Hall, 2006.

Outside Links

- This is not meant for references used for constructing the module, but as secondary and unvetted information available at other site

- Link to outside sources. Wikipedia entries should probably be referenced here.