6.11: More Molecular Orbital Theory and Intermolecular Forces

- Page ID

- 408821

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)More MO Theory

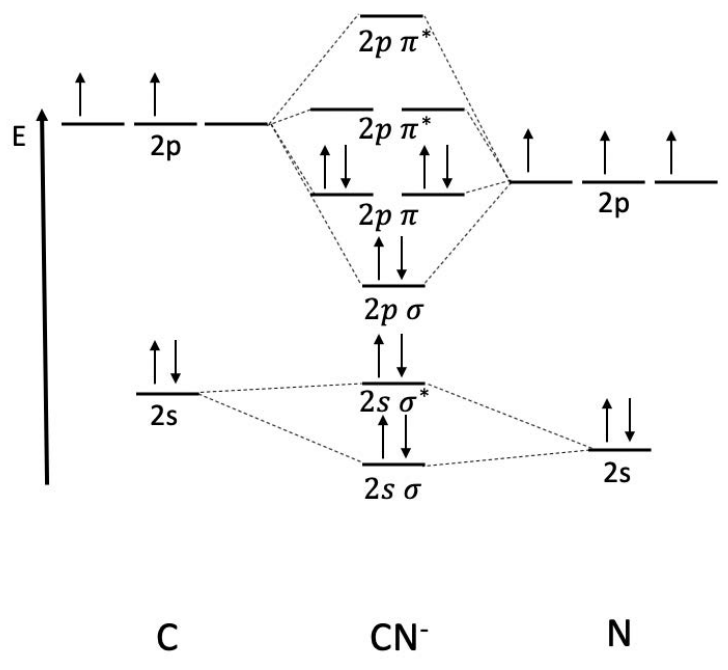

So far we’ve discussed \(\mathrm{MO}\) diagrams with homogeneous dimers: both atoms are the same. But there can also be heterogenous dimers involving two different atoms, and these dimers can be charged! When we construct a \(\mathrm{MO}\) diagram for a heterogeneous dimer, it is the same principle as for a homogeneous dimer: draw electronic orbital diagrams for each atom, populate the electronic states, and then fil in the sigma and pi bonding and antibonding states formed. The only difference in the case of the heterogeneous dimer is that we must consider the relative energy of each set of atomic orbitals. This often yields asymmetric \(\mathrm{MO}\) diagrams. Typically, the more electronegative atom is lower in energy.

Example: Draw the \(\mathrm{MO}\) diagram of \(\mathrm{CN}^-\). Determine the bond order.

- Answer

-

Nitrogen is lower along the energy axis because it is more electronegative than carbon, yielding an asymmetric \(\mathrm{MO}\) diagram. There are 8 electrons in bonding orbitals and 2 electrons in antibonding orbitals, so the bond order is

\(\text { bond order }=\dfrac{1}{2}(8-2)=3\)

A dimer with bond order 3 is triple bonded! You may recognize this molecule as cyanide.

Intermolecular Forces (IMFs)

London Dispersion Forces (LDFs) exist in all molecules. As the electrons distributed across a molecule fluctuate in time, they generate small electric fields. Then, electrons in other molecules or atoms that are in close proximity rearrange in response to the generated electric fields. Molecules with more electrons experience stronger LDFs.

Dipole-dipole interactions are IMFs characterized by electrostatic force between polar molecules. The more polar the molecule, the stronger the interaction.

Hydrogen bonds (\(\mathrm{H}\)-bonds) are a particular type of dipole-dipole interaction that occur in molecules with a hydrogen atom \((\mathrm{H})\) bonded directly to a fluorine, oxygen, or nitrogen atom (\(\mathrm{F}\), \(\mathrm{O}\), or \(\mathrm{N})\).

Generally, LDFs are weaker than dipole-dipole interactions, and \(\mathrm{H}\)-bonds are strongest of all. However, there is no way to apply a one-size-fits-all classification of IMF strength, as they depend on specific molecular geometry, steric bulk (how big the molecule is), arrangement of atoms, polarity, and other factors. If a substance contains molecules with stronger IMFs, it requires more energy to break apart the molecules, which generally means that materials with stronger IMFs have higher melting points and higher boiling points.

Example: Will it \(\mathrm{H}\)-bond? Circle the molecules that form hydrogen bonds in solution.

- Answer

-

1. This molecule has a ring of carbons, and each carbon is also bonded to one hydrogen. There are no \(\mathrm{H}-\mathrm{F}\), \(\mathrm{H}-\mathrm{O}\), or \(\mathrm{H}-\mathrm{N}\) bonds, so this molecule does not form \(\mathrm{H}\)-bonds.

2. Here, the molecule is shown in a notation typical of organic chemistry: each vertex along the line connecting \(\mathrm{HO}\) and \(\mathrm{CH}_2\) contains a carbon atom + hydrogen atoms to complete the octet, and the lines connecting the vertices represent bonds. Written another way, this molecule is \(\mathrm{HO}-\mathrm{CH}_2-\mathrm{CH}=\mathrm{CH}_2\). None of the \(\mathrm{C}-\mathrm{H}\) bonds participate in hydrogen bonding, but the \(\mathrm{HO}\) groups will form \(\mathrm{H}\)-bonds with the other \(\mathrm{HO}\) groups!

3. Similar to the first one, this molecule only contains bonds between \(\mathrm{C}\) and \(\mathrm{H}\) atoms. It will not form \(\mathrm{H}\) bonds.

4. There is a lot going on with this molecule. The rings here are the same sort of structure as the ring in 1: you can imagine filling in a \(\mathrm{C}\) at each vertex and then populating with \(\mathrm{H}\) to fill out the octets. This molecule contains \(\mathrm{N}\), but all of the \(\mathrm{N}\) atoms are bonded only to \(\mathrm{C}\): these \(\mathrm{N}-\mathrm{C}\) groups won't form \(\mathrm{H}\) bonds. However, there are some \(\mathrm{OH}\) groups: these will form \(\mathrm{H}\)-bonds with the \(\mathrm{OH}\) groups on neighboring molecules!

5. You might recognize this molecule as ammonia. Here, the \(\mathrm{N}\) atom is directly bonded to hydrogen. These \(\mathrm{N}-\mathrm{H}\) end groups will form \(\mathrm{H}\)-bonds.

6. Finally, this hydrofluoric acid molecule is just \(\mathrm{H}-\mathrm{F}\). Therefore, it will form \(\mathrm{H}\)-bonds.