8.3: Hydrides

- Page ID

- 212660

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Trihydrides of the Group 15 Elements

All five of the Group 15 elements form hydrides of the formula EH3. Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) lists the IUPAC names along with those in more common usage.

| Compound | Traditional name | IUPAC name |

|---|---|---|

| NH3 | Ammonia | Azane |

| PH3 | Phosphine | Phosphane |

| AsH3 | Arsine | Arsane |

| SbH3 | Stibine | Stibane |

| BiH3 | Bismuthine | Bismuthane |

The boiling point and melting point increase increases going down the Group (Table \(\PageIndex{2}\)) with increased molecular mass, with the exception of NH3 whose anomalously high melting and boiling points (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)) are a consequence of strong N-H...H hydrogen bonding. A similar (and stronger) effect is observed for the Group 16 hydrides (H2E).

| Compound | Mp (°C) | Bp (°C) | ΔHf (kJ/mol) | E-H bond energy (kJ/mol) | H-E-H bond angle (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NH3 | -77.7 | -33.35 | -46.2 | 391 | 107 |

| PH3 | -133 | -87.7 | 9.3 | 322 | 93.5 |

| AsH3 | -116.3 | -55 | 172.2 | 247 | 92 |

| SbH3 | -88 | -17.1 | 142.8 | 255 | 91.5 |

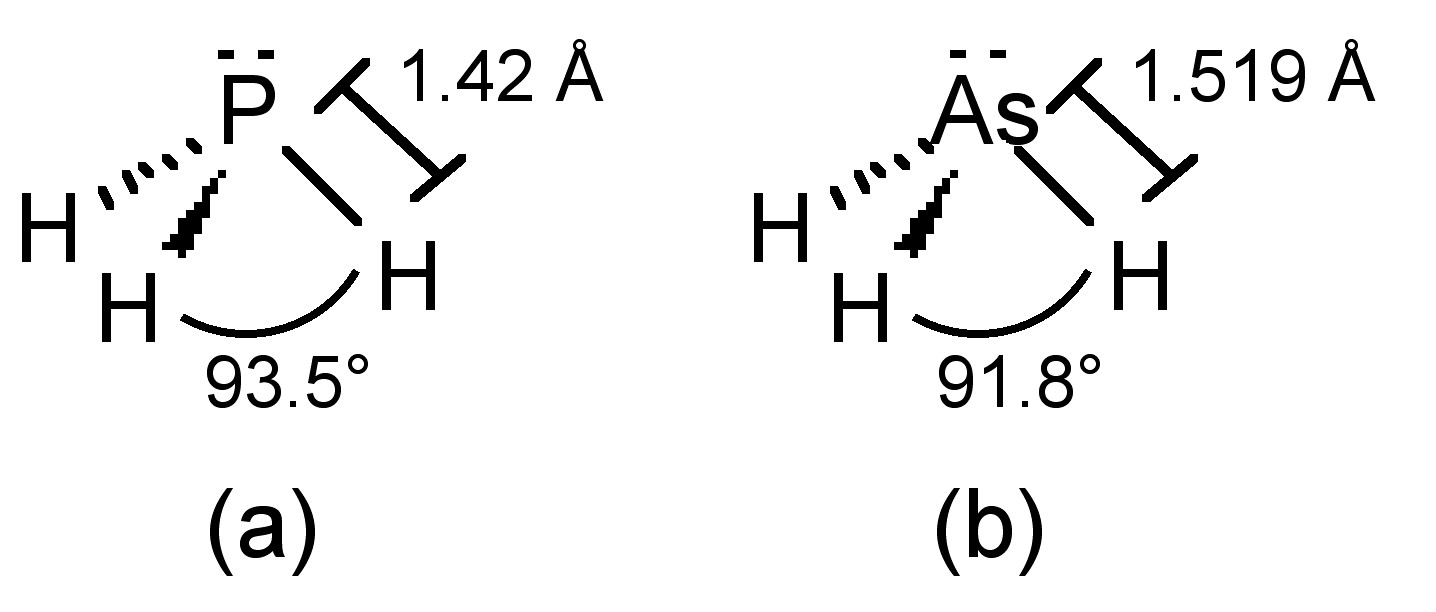

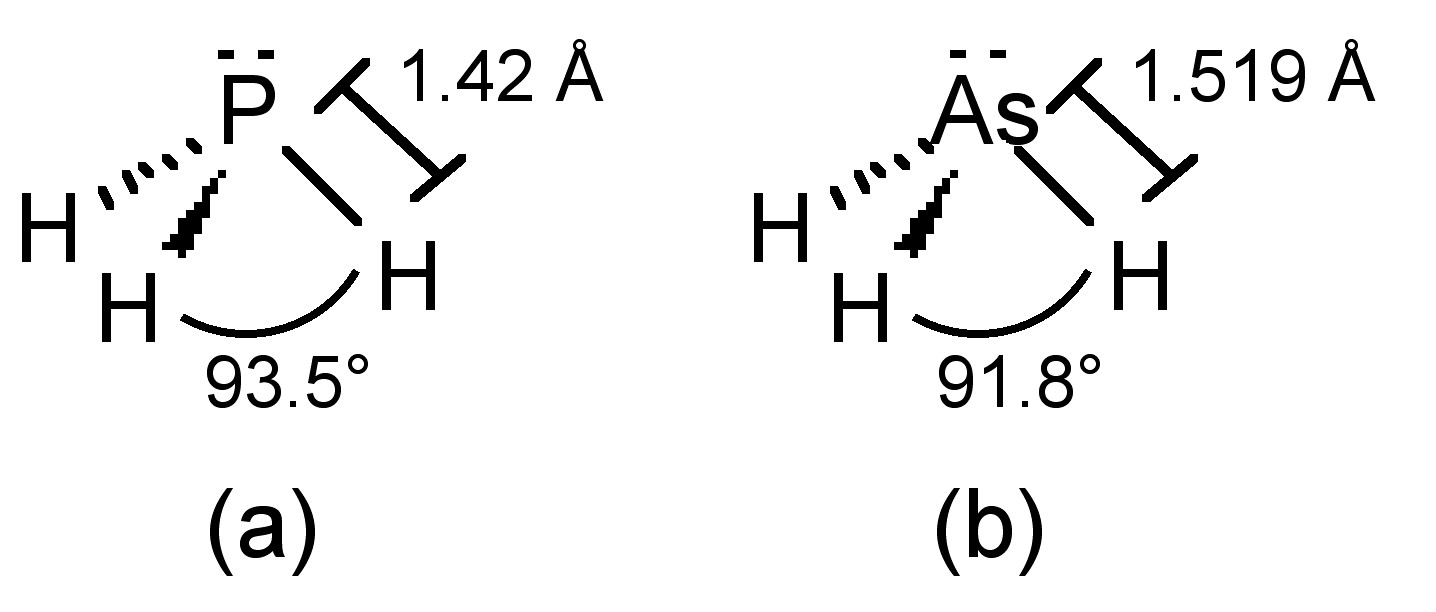

The E-H bond strengths decrease down the group and this correlates with the overall stability of each compound (Table \(\PageIndex{2}\)). The H-E-H bond angles (Table \(\PageIndex{2}\)) also decrease down the Group. The H-E-H bond angle is expected to be a tetrahedral ideal of 109.5°, but since lone pairs repel more than bonding pairs, the actual angle would be expected to be slightly smaller. Two possible explanations are possible for the difference between NH3 and the other hydrides.

- The N-H bond is short (1.015 Å) compared to the heavier analogs, and nitrogen is more electronegative than hydrogen, so the bonding pair will reside closer to the central atom and the bonding pairs will repel each other opening the H-N-H angle more than observed for PH3, etc.

- The accessibility of the 2s and 2p orbitals on nitrogen allows for hybridization and the orbitals associated with N-H bonding in NH3 are therefore close to sp3 in character, resulting in a close to tetrahedral geometry. In contrast, hybridization of the ns and np orbitals for P, As, etc., is less accessible, and as a consequence the orbitals associated with P-H bonding in PH3 are closer to p in character resulting in almost 90° H-P-H angle. The lower down the Group the central atom the less hybridization that occurs and the closer to pure p-character the orbitals on E associated with the E-H bond.

Ammonia

Ammonia (NH3) is a colorless, pungent gas (bp = -33.5 °C) whose odor can be detected at concentrations as low 20 – 50 ppm. Its high boiling point relative to its heavier congeners is indicative of the formation of strong hydrogen bonding. The strong hydrogen bonding also results in a high heat of vaporization (23.35 kJ/mol) and thus ammonia can be conveniently used as a liquid at room temperature despite its low boiling point.

WARNING

Ammonia solution causes burns and irritation to the eyes and skin. The vapor causes severe irritation to the respiratory system. If swallowed the solution causes severe internal damage.

Synthesis

Ammonia is manufactured on the industrial scale by the Haber process using the direct reaction of nitrogen with hydrogen at high pressure (102 – 103 atm) and high temperature (400 – 550 °C) over a catalyst (e.g., α-iron), (8.3.1).

\[\text{N}_2\text{ + 3 H}_2\rightarrow \text{2 NH}_3\]

On the smaller scale ammonia is prepared by the reaction of an ammonium salt with a base, (8.3.2), or hydrolysis of a nitride, (8.3.3). The latter is a convenient route to ND3 by the use of D2O.

\[\text{NH}_4\text{X + OH}^- \rightarrow \text{NH}_3\text{ + H}_2\text{O + X}^-\]

\[\text{Mg}_3\text{N}_2\text{ + H}_2\text{O} \rightarrow \text{3 Mg(OH)}_2 \text{ + 2 NH}_3\]

Structure

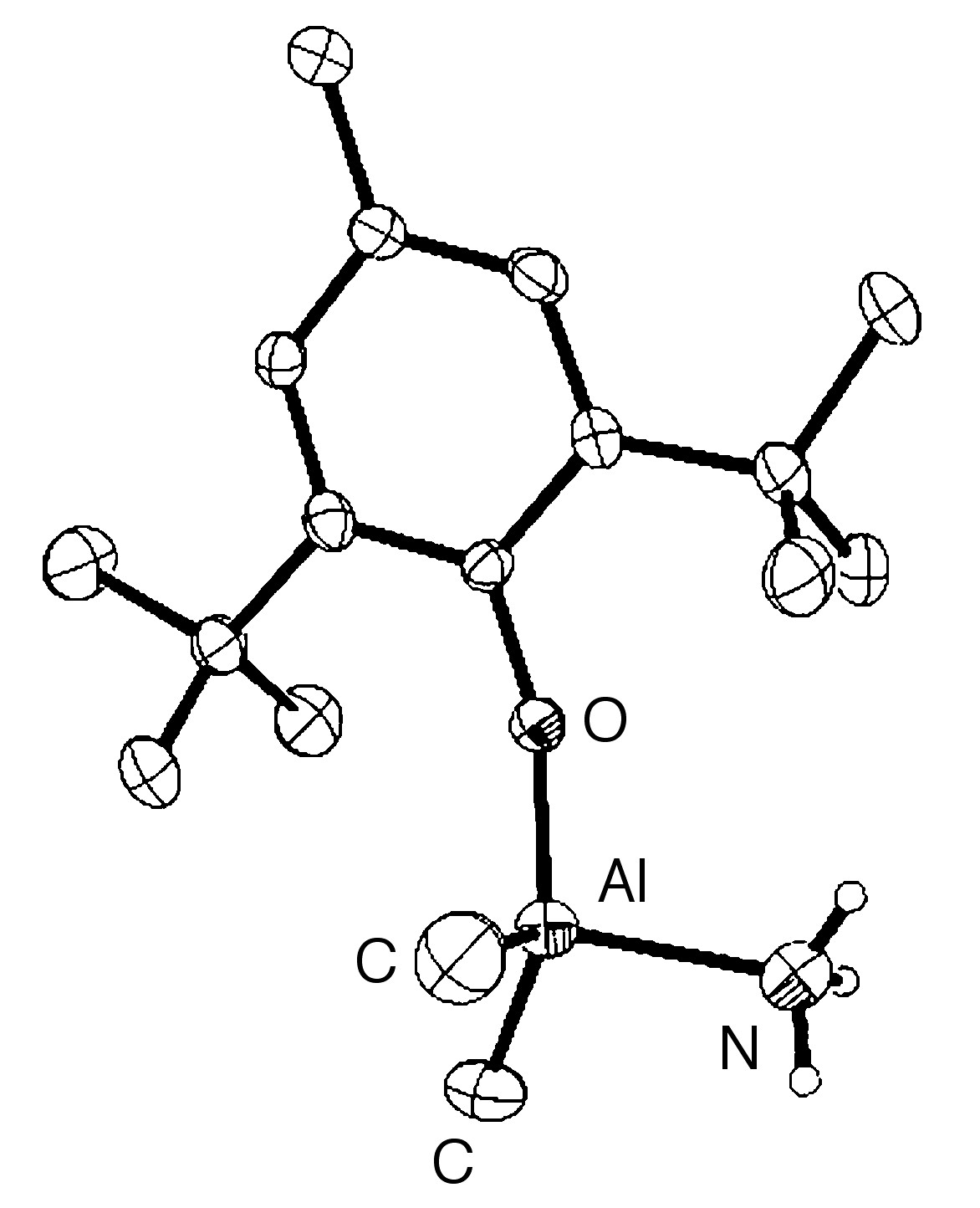

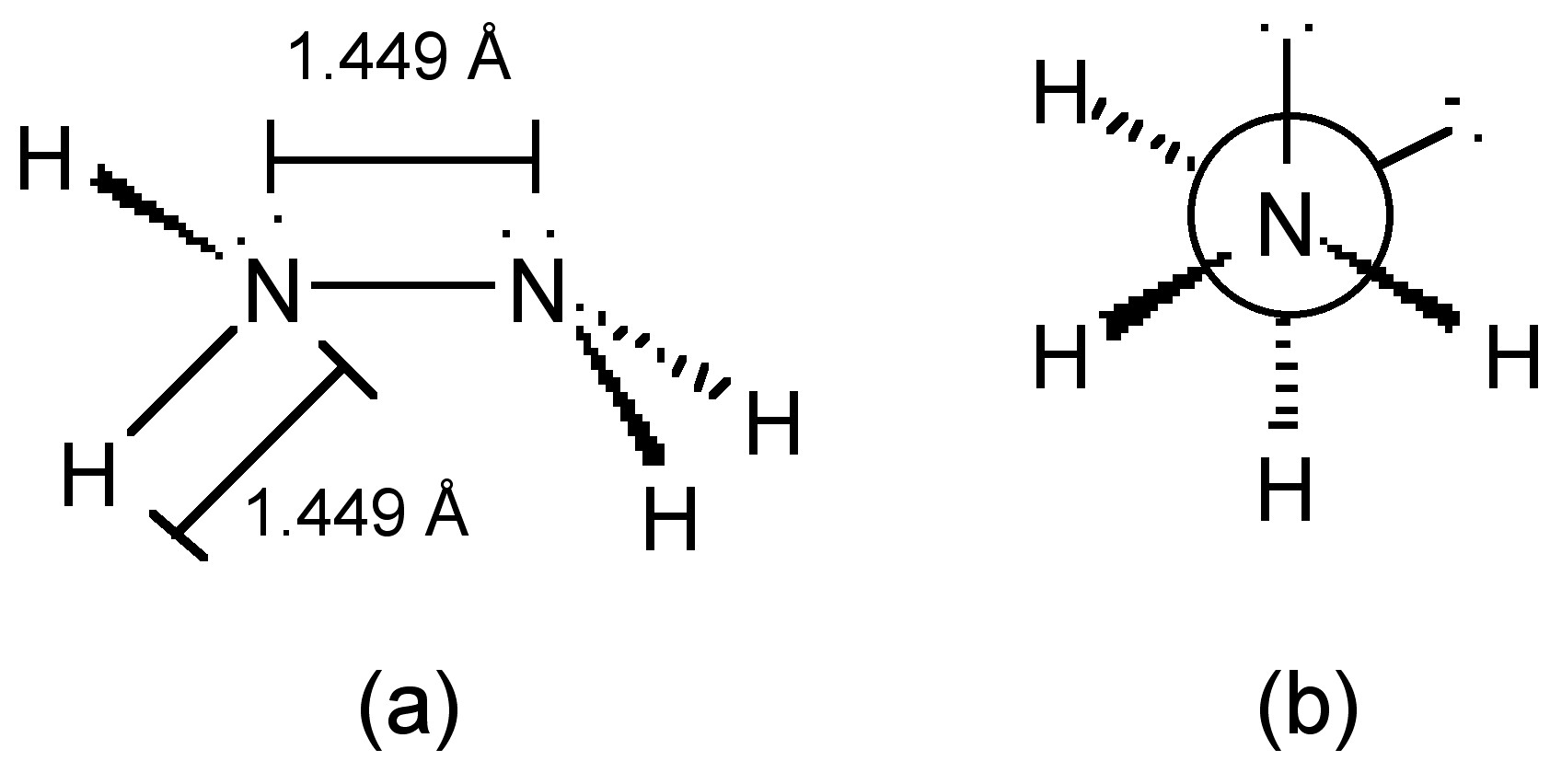

The nitrogen in ammonia adopts sp3 hybridization, and ammonia has an umbrella structure (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)) due to the stereochemically active lone pair.

The barrier to inversion of the umbrella is very low (Ea = 24 kJ/mol) and the inversion occurs 100’s of times a second. As a consequence it is not possible to isolate chiral amines in the same manner that is possible for phosphines.

In a similar manner to water, (8.3.4), ammonia is a self-ionizing, (8.3.5); however, the equilibrium constant (K = 10-33) is much lower than water (K = 10-14). The lower dielectric constant of ammonia (16.5 @ 20 °C) as compared to water (80.4 @ 20 °C) means that ammonia is not as good as water as a solvent for ionic compounds, but is better for covalent organic compounds.

\[\text{2 H}_2\text{O} \rightleftharpoons \text{H}_3\text{O}^+\text{ + OH}^-\]

\[\text{2 NH}_3 \rightleftharpoons \underset{\text{ammonium}}{\textext{NH}_4^+} \t{ + } \und\terset{ext{amide}}{\text{NH}_2^- }\]

Reactions

The similarity of ammonia and water means that the two compounds are miscible. In fact, ammonia forms a series of solid hydrates, analogous to ice in which hydrogen bonding defines the structures (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). Several hydrates of ammonia are known, including: NH3.2H2O (ammonia dihydrate, ADH), NH3.H2O (ammonia monohydrate, AMH), and 2NH3.2H2O (ammonia hemihydrate, AHH).

It should be noted that these hydrates do not contain discrete NH4+ or OH- ions, indicating that ammonium hydroxide does not exist as a discrete species despite the common useage of the name. In aqueous solution, ammonia is a weak base (pKb = 4.75), (8.3.6).

\[ \rm NH_{3(aq)} + H_2O_{(l)} \rightleftharpoons NH_{4(aq)}^+ + OH^-_{(aq)}\]

Note

Ammonia solutions commonly used in the laboratory is a 35% solution in water. In warm weather the solution develops pressure and the cap must be released with care. The 25% solution sold commercially (for home use) is free from this problem.

Ammonia is a Lewis base and readily forms Lewis acid-base complexes with both transition metals, (8.3.7), and main group metals (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)).

\[ \rm [Ni(H_2O)_6]^{2+} + 6 NH_3 \rightleftharpoons [Ni(NH_3)_6]^{2+} + 6 H_2O\]

The formation of stable ammonia complexes is the basis of a simple but effective method of detection: Nessler’s reagent, (8.3.8). Using a 0.09 mol/L solution of potassium tetraiodomercurate(II), K2[HgI4], in 2.5 mol/L potassium hydroxide. A yellow coloration indicates the presence of ammonia: at higher concentrations, a brown precipitate may form. The sensitivity as a spot test is about 0.3 μg NH3 in 2 μL.

\[\rm NH_4^+ + 2 [HgI_4]^{2-} + 4 OH^- \rightarrow HgO\cdotHg(NH_2)I + 7 I^- + 3 H_2O\]

Ammonia forms a blue solution with Group 1 metals. As an example, the dissolution of sodium in liquid ammonia results in the formation of solvated Na+ cations and electrons, (8.3.9) where solv = NH3. The solvated electrons are stable in liquid ammonia and form a complex: [e-(NH3)6].

\[ \rm Na_{(s)} \rightarrow Na_{(solv)} \rightleftharpoons Na^+_{(solv)} + e_{(solv)}^-\]

It is this solvated electron that gives the strong reducing properties of the solution as well as the characteristic signal in the ESR spectrum associated with a single unpaired electron. The blue color of the solution is often ascribed to these solvated electrons; however, their absorption is in the far infra-red region of the spectrum. A second species, Na-(solv), is actually responsible for the blue color of the solution.

\[\rm 2 Na_{(solv)} \rightleftharpoons Na^+_{(solv)} + Na^-_{(solv)} \]

The reaction of ammonia with oxygen is highly favored, (8.3.11), and the flammability limit of ammonia is 16 – 25 vol%. If the reaction is carried out in the presence of a catalyst (Pt or Pd) the reaction can be limited to the formation of nitric oxide (NO), (8.3.12).

\[\rm 4 NH_3 + 3 O_2 \rightarrow 2 N_2 + 6 H_2O \]

\[\rm 4 NH_3 + 5 O_2 \rightarrow 4 NO + 6 H_2O \]

Ammonium salts

The ammonium cation (NH4+) behaves in a similar manner to the Group 1 metal ions. The solubility and structure of ammonium salts particularly resembles those of potassium and rubidium because of their relative size (Table \(\PageIndex{3}\)). One difference is that ammonium salts often decompose upon heating, (8.3.13).

\[\rm NH_4Cl_{(s)} \rightarrow NH_{3(g)} + HCl_{(g)}\]

| Cation | Ionic radius (Å) |

|---|---|

| K+ | 1.33 |

| NH4+ | 1.43 |

| Rb+ | 1.47 |

The decomposition of ammonium salts of oxidizing acids can often be violent to highly explosive, and they should be treated with care. For example, while ammonium dichromate, (NH4)2Cr2O7, decomposes to give a volcano (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)), ammonium permanganate, NH4[MnO4], is friction sensitive and explodes at 60 °C. Ammonium nitrate, NH4[NO3], can cause fire if contacted with a combustible material and is a common ingredient in explosives since it acts as the oxygen source due to its positive oxygen balance, i.e., the compound liberates oxygen surplus to its own needs upon decomposition, (8.3.14).

\[\rm NH_4[NO_3] \rightarrow H_2O + N_2 + O\]

Bibliography

- A. R. Barron, The Detonator, 2009, 36, 60.

- A. D. Fortes, E. Suard, M. -H. Lemée-Cailleau, C. J. Pickard, and R. J. Needs, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2009, 131, 13508.

- M. D. Healy, J. T. Leman, and A. R. Barron, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1991, 113, 2776.

- A. I. Vogel and G. Svehla, Textbook of Macro and Semimicro Qualitative Inorganic Analysis, Longman, London (1979).

Liquid Ammonia as a Solvent

Ammonia has a reasonable liquid range (-77 to –33 °C), and as such it can be readily liquefied with dry ice (solid CO2, Tsub = -78.5 °C), and handled in a thermos flask. Ammonia’s high boiling point relative to its heavier congeners is indicative of the formation of strong hydrogen bonding, which also results in a high heat of vaporization (23.35 kJ/mol). As a consequence ammonia can be conveniently used as a liquid at room temperature despite its low boiling point.

Liquid ammonia is a good solvent for organic molecules (e.g., esters, amines, benzene, and alcohols). It is a better solvent for organic compounds than water, but a worse solvent for inorganic compounds. The solubility of inorganic salts is highly dependant on the identity of the counter ion (Table \(\PageIndex{4}\)).

| Soluble in liquid NH3 | Generally insoluble in liquid NH3 |

|---|---|

| SCN-, I-, NH4+, NO3-, NO2-, ClO4- | F-, Cl-, Br-, CO32-, SO42-, O2-, OH-, S2- |

The difference in solubility of inorganic salts in ammonia as compared to water, as well as the lower temperature of liquid ammonia, can be used to good advantage in the isolation of unstable compounds. For example, the attempted synthesis of ammonium nitrate by the reaction of sodium nitrate and ammonium chloride in water results in the formation of nitrogen and water due to the decomposition of the nitrate, (8.3.15). By contrast, if the reaction is carried out in liquid ammonia, the sodium chloride side product is insoluble and the ammonium nitrate may be isolated as a white solid after filtration and evaporation below its decomposition temperature of 0 °C, (8.3.16).

\[ \rm NaNO_2 + NH_4Cl \xrightarrow{H_2O} NaCl + NH_4(NO_2) \rightarrow N_2 + 2 H_2O\]

\[ \rm NaNO_2 + NH_4Cl \xrightarrow{NH_3} NaCl \downarrow + NH_4(NO_2) \]

Ammonation

Ammonation is defined as a reaction in which ammonia is added to other molecules or ions by covalent bond formation utilizing the unshared pair of electrons on the nitrogen atom, or through ion-dipole electrostatic interactions. In simple terms the resulting ammine complex is formed when the ammonia is acting as a Lewis base to a Lewis acid, (8.3.17) and (8.3.18), or as a ligand to a cation, e.g., [Pt(NH3)4]2+, [Ni(NH3)6]2+, [Cr(NH3)6]3+, and [Co(NH3)6]3+.

\[ \rm SiF_4 + 2 NH_3 \rightarrow SiF_4(NH_3)_2 \]

\[ \rm BF_3 + NH_3 \rightarrow BF_3(NH_3)\]

Ammonolysis

Ammonolysis with ammonia is an analogous reaction to hydrolysis with water, i.e., a dissociation reaction of the ammonia molecule producing H+ and an NH2- species. Ammonolysis reactions occur with inorganic halides, (8.3.18) and (8.3.19), and organometallic compounds, (8.3.20). In both case the NH2- moiety forms a substituent or ligand.

\[ \rm P(O)Cl_3 + 6 NH_3 \rightarrow P(O)(NH_2)_3 + 3 NH_4Cl\]

\[ \rm BCl_3 + 6 NH_3 \rightarrow B(NH_2)_3 + 3 NH_4Cl \]

\[ \rm Al(CH_3)_3 + NH_3 \rightarrow \dfrac{1}{n}[(H_3C)_2Al(NH_2)]_n + CH_4\]

The reaction of esters, (8.3.21), and aryl halides, (8.3.22), are also examples of ammonolysis reactions.

\[ \rm RC(O)OR' + NH_3 \rightarrow RC(O)NH_2 + R'OH\]

\[ \rm C_6H_5Cl + 2 NH_3 \rightarrow C_6H_5NH_2 + NH_4Cl\]

Homoleptic amides

A homoleptic compound is a compound with all the ligands being identical, e.g., M(NH2)n. A general route to homoleptic amide compounds is accomplished by the reaction of a salt of the desired metal that is soluble in liquid ammonia (Table \(\PageIndex{4}\)) with a soluble Group 1 amide. The solubility of the Group 1 amides is given in Table \(\PageIndex{5}\). Since all amides are insoluble (except those of the Group 1 metals) are insoluble in liquid ammonia, the resulting amide may be readily isolated, e.g., (8.3.23) and (8.3.24).

\[ \rm Mn(SCN)_2 + 2 KNH_2 \rightarrow Mn(NH_2)_2 \downarrow + 2 KSCN\]

\[ \rm Cr(NO_3)_3 + 3 KNH_2 \rightarrow Cr(NH_2)_3 \downarrow + 3 KNO_3\]

| Amide | Solubility in liquid ammonia |

| LiNH2 | Sparingly soluble |

| NaNH2 | Sparingly soluble |

| KNH2 | Soluble |

| RbNH2 | Soluble |

| CsNH2 | Soluble |

Redox reactions

Ammonia is poor as an oxidant since it is relatively easily oxidized, e.g., (8.3.25) and (8.3.26). Thus, if it is necessary to perform an oxidation reaction ammonia is not a suitable solvent; however, it is a good solvent for reduction reactions.

\[ \rm 4 NH_3 + 5 O_2 \rightarrow 4 NO + 6 H_2O \]

\[ \rm 2 NH_3 + 3 CuO \rightarrow N_2 + 3 H_2O + 3 Cu\]

Liquid ammonia will dissolve Group 1 (alkali) metals and other electropositive metals such as calcium, strontium, barium, magnesium, aluminum, europium, and ytterbium. At low concentrations (ca. 0.06 mol/L), deep blue solutions are formed: these contain metal cations and solvated electrons, (8.3.27). The solvated electrons are stable in liquid ammonia and form a complex: [e-(NH3)6].

\[ \rm Na_{(s)} \rightarrow Na_{(solv)} \rightleftharpoons Na^+_{(solv)} + e^-_{(solv)}\]

The solvated electrons provide a suitable and powerful reducing agent for a range of reactions that are not ordinarily accomplished, e.g., (8.3.28) and (8.3.29).

\[ \rm [Ni(CN)_4]^{2-} + 2 e^-_{(solv)} \rightarrow [Ni(CN)_4]^{4-}\]

\[ \rm Co_2(CO)_8 + 2 e^-_{(solv)} \rightarrow 2 [Co(CO)_4]^-

The rapid increase in the German population also put a strain on the countries food resources. What compounded this issue was that the aristocratic Junkers families of East Prussia who owned much of the land in what was known as Germany’s breadbasket. Junkers grew rye on their estates because the soil was too light for wheat, and since rye was fertilized with potash (potassium oxide, K2O) of which Germany had vast resources. However, in 1870 grain from the US was becoming cheaper and thus competitive with German rye. To protect their profits the Junkers demanded both subsidies for the export of rye and tariffs for the import of wheat. The result of this was that all the German rye was leaving the country and there was not enough wheat being produced to satisfy the needs of the local population. Sufficient wheat could be grown in Germany if a suitable fertilizer was available.

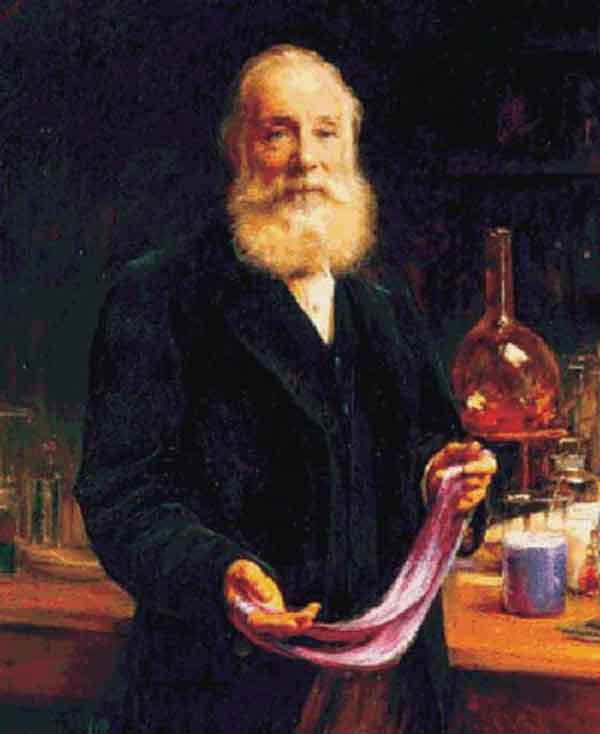

Sodium nitrate (NaNO3), also known as Chile saltpeter, was the most common fertilizer. Unfortunately, by 1900 the deposits looked to be depleted and an alternative was needed. The alternative was found as a component in coal tar. It was known that one of the chemicals that caused the stink associated with coal gas and coal tar was ammonia (NH3). Chemist George Fownes (Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)) had suggested that ammonia be turned into a salt and used as a fertilizer. Unfortunately, the amount of ammonia that could be separated from coal tar was still insufficient, so if ammonia could be made on a large enough scale, then large-scale manufacture of a fertilizer could be realized.

In 1909 Fritz Haber (Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)) presented a method of ammonia synthesis to BASF. His work in collaboration with Carl Bosch (Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\)) resulted in the process known as the Haber-Bosch process in which nitrogen and hydrogen are mixed at high temperature (600 °C) under pressure (200 atm) over an osmium catalyst, (8.3.30).

\[ \rm N_2 + 3 H_2 \xrightarrow{\text{Os cat}} 6 NH_3 \]

It is interesting to note that the realization of the Haber-Bosch process required not only high-pressure vessels to be constructed by the steel industry, but also the liquid forms of nitrogen and hydrogen. As it turned out ammonia was a necessary component for enabling the production of liquid nitrogen and hydrogen, and involved a false hypothesis of what caused malaria, which led to a desire to keep drinks cold.

Long before it was understood the real cause of malaria, John Gorrie (Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\)), a doctor working in Apalachicola on the Gulf Coast of Florida, was obsessed with finding a cure for malaria. The term malaria originated from Medieval Italian: mala aria (bad air), and it was associated with swamps and marshlands. Gorrie noticed that malaria was connected to hot humid weather so he began hanging bowl of ice in wards and circulating the air with a fan. However, ice was cut from frozen lakes and rivers in the North East of the US, stored and then shipped all over the world, and Apalachicola was so small that ice was seldom delivered. Gorrie started looking into methods of making ice. It was well known that when a compressed gas expands it takes heat from its surroundings. Gorrie made a steam engine that compressed air in a piston, which when the piston retracted the air cooled. On the next compression stroke the cold air was pushed out across a brine solution (saturated aqueous NaCl) cooling it. When he brought water in contact with the cold brine, it froze creating the first man made ice. On 14 July 1850 Gorrie produced ice for the French Consul to cool the champagne for the celebration of Bastille Day. Just before he died, Gorrie suggested that his (by then) Patented process could be used for cooling food for transport, and it was this application that was used extensively by British merchants to bring meat from Australia to Britain. However, in Germany, Gorrie’s invention was more useful for beer.

Whereas the British traditionally brewed beer in which the yeast ferments on the surface (top fermentation) at a temperature of 60 – 70 °F, in Germany beer was made using bottom fermentation. This style of fermentation requires a temperature just above freezing. Traditionally, cold cellars were used to store the fermenting beer, and it is from here the name lager is derived from the German verb largern: to store. There had been a law in Germany preventing brewing in the summer, but with Gorrie’s process the possibility was to be able to brew beer all year. Carl von Linde (Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\)) was asked to develop a refrigeration system. He used ammonia instead of air in Gorrie’s system, and in 1879 he set up a company to commercialize his ideas. The success of his refrigerator was such that by 1891 there were over 12,000 fridges being used, and more importantly there was now a convenient method of liquefying gases such as hydrogen and nitrogen; both of which were needed for the Haber-Bosch process.

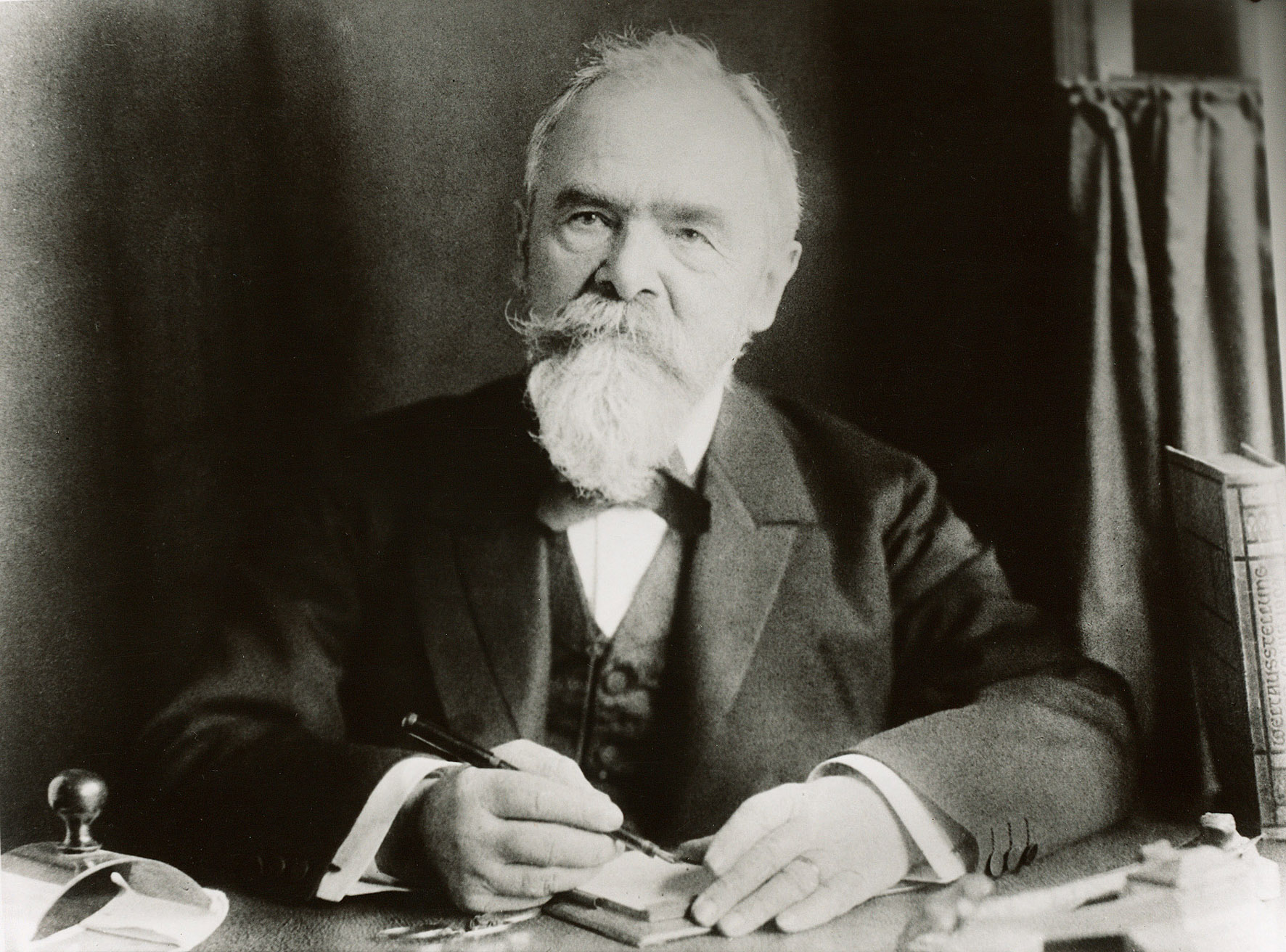

As a consequence of the use of ammonia as a refrigerant, it was possible to prepare ammonia on a large industrial scale. Ammonia prepared by the Haber-Bosch process can be converted to nitric acid by the Ostwald process developed by Wilhelm Ostwald (Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\)). Treatment of ammonia with air over a platinum catalyst yields initially nitric oxide, (8.3.31), and subsequently to nitrogen dioxide, (8.3.32), which dissolves in water to give nitric acid, (8.3.33).

\[ \rm 4 NH_3 + 5 O_2 \xrightarrow{\text{Pt cat}} 4 NO + 6 H_2O \]

\[ \rm 2 NO + O_2 \xrightarrow{\text{Pt cat}} 2 NO_2 \]

\[ \rm 3 NO_2 + H_2O \rightarrow 2 HNO_3 + NO\]

Addition of soda (sodium hydroxide, NaOH) to nitric acid results in the formation of sodium nitrate, (8.3.34), which was the same fertilizer produced from the deposits in Chile.

\[ \rm HNO_3 + NaOH \rightarrow NaNO_3 + H_2O \]

Unfortunately, for the Haber-Bosch and Ostwald processes, an even cheaper form of fertilizer was synthesized around the same time using calcium carbide to prepare calcium cyanamide (CaCN2), (8.3.35). As a consequence, the Haber-Bosch process was forgotten until the outbreak of the First World War in 1914.

\[ \rm CaC_2 + N_2 \rightarrow CaCN_2 + C\]

Within weeks of the outbreak Germany realized it had only enough explosives for about a year of conflict. This was because the main source of explosives, sodium nitrate was the same source that gave fertilizer, i.e., Chile. Realizing this, the Royal Navy effectively blockaded the supply lines. If Germany did not find another source of Great War would have been over early in 1916, however, it was remembered that the Haber-Bosch process in combination with the Ostwald processes would allow the synthesis of nitric acid, which when mixed with cotton, made nitrocellulose (Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\)), also known as gun cotton, an explosive, (8.3.36).

\[ \rm HNO_3 + C_6H_{10}O_5 \rightarrow C_6H_7(NO_2)_3O_5 + 3 H_2O \]

As a result of the industrial synthesis of ammonia Germany was able to manufacture sufficient explosives to fight until 11 November 1918, by which time almost 10 million were dead, almost 7 million missing, and over 21 million were wounded (Figure \(\PageIndex{15}\)).

Hydrazine

Hydrazine (N2H4) is a colorless liquid with an odor similar to ammonia. Hydrazine has physical properties very close to water, with a melting point of 2 °C and a boiling point of 114 °C. The similarity in its chemistry to water is as a result of strong intermolecular hydrogen bonding.

WARNING

Hydrazine is highly toxic and dangerously unstable, and is usually handled as aqueous solution for safety reasons. Even so, hydrazine hydrate causes severe burns on the skin and eyes. Contact with transition metals, their oxides (e.g., rust), or salts cause catalytic decomposition and possible ignition of evolved hydrogen. Reactions with oxidants are violent.

Synthesis

Hydrazine is manufactured on the industrial scale by the Olin Raschig process using the reaction of a sodium hypochlorite solution with ammonia at 5 °C to form chloramine (NH2Cl) and sodium hydroxide, (8.3.37). The chloramines solution is the reacted with ammonia under pressure at 130 °C, (8.3.38). Ammonia is used in a 33 fold excess.

\[ \rm NH_3 + OCl^- \rightarrow OH^- + NH_2Cl \]

\[ \rm NH_2Cl + OH^- + NH_3 \rightarrow N_2H_4 + Cl^- + H_2O \]

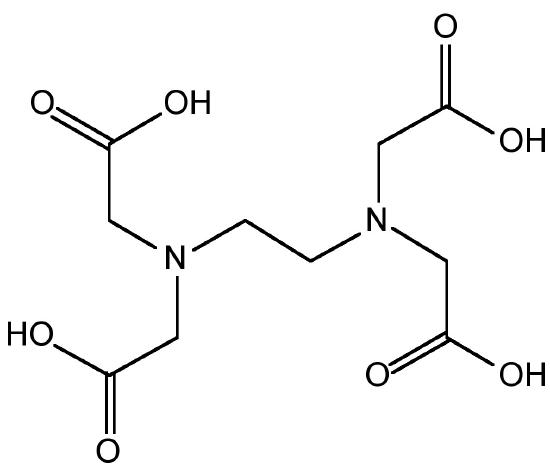

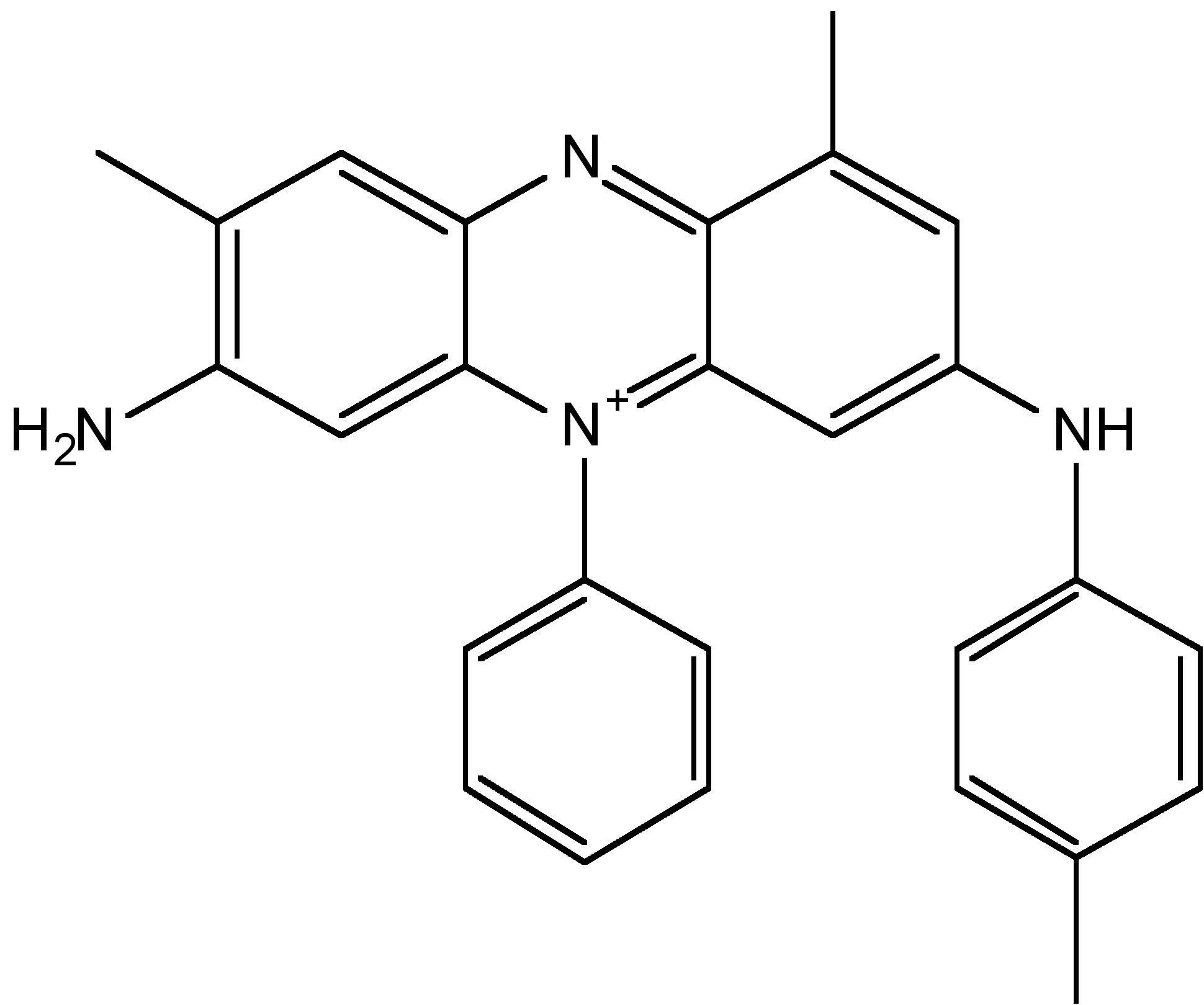

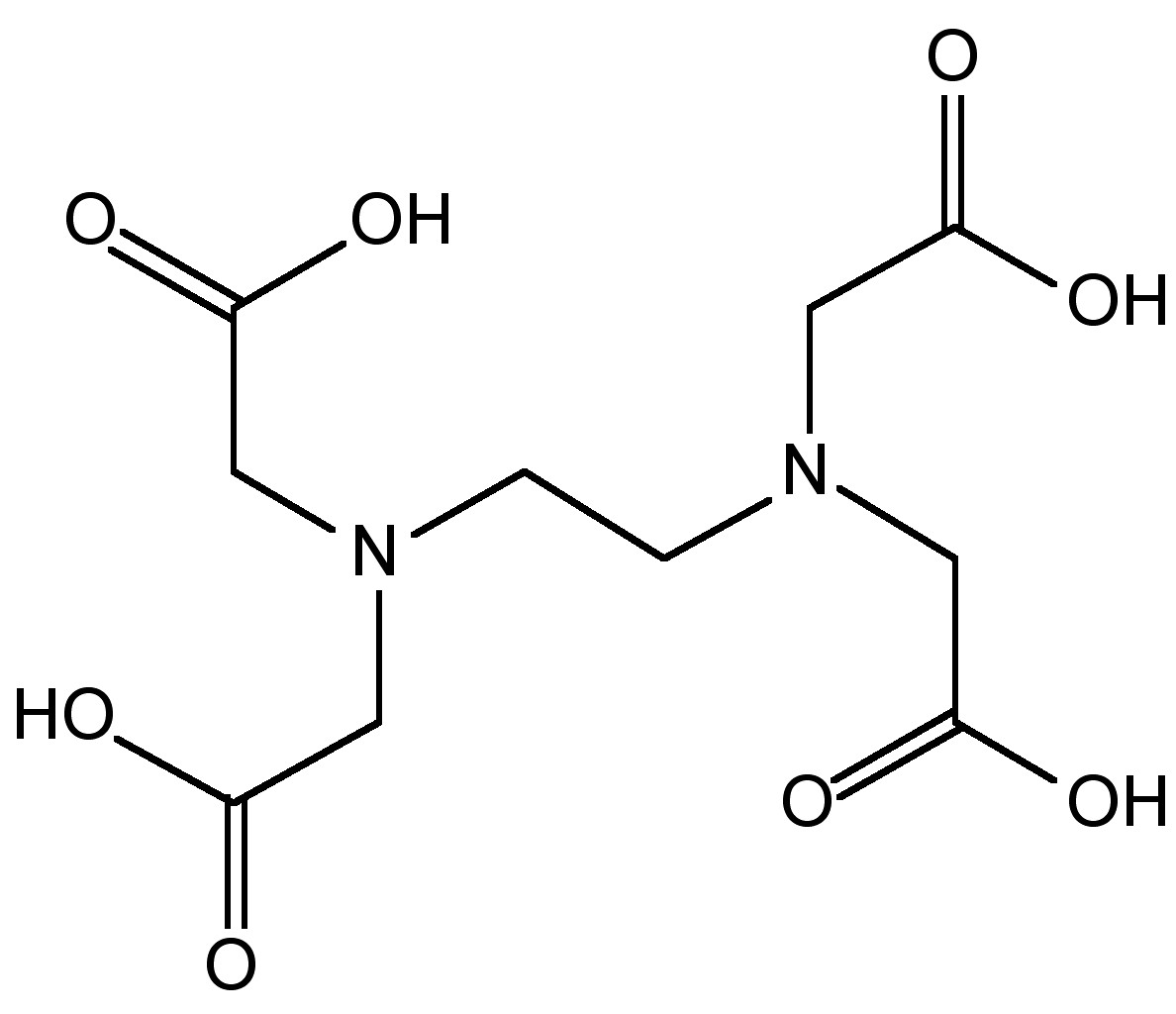

If transition metals are present then decomposition occurs, (8.3.38), and therefore, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA, Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\)) is added to complex the transition metal ions. The as produced hydrazine solution can be concentrated by distillation to give a 65% solution. Anhydrous hydrazine is formed by the distillation from NaOH.

\[ \rm 2 NH_2Cl + N_2H_4 \rightarrow 2 NH_4^+ + 2 Cl^- + N_2\]

Alternative routes to hydrazine include the oxidation of urea with sodium hypochlorite, (8.3.40), and the reaction of ammonia and hydrogen peroxide, (8.3.41).

\[ \rm (H_2N)_2\text{C=O} + NaOCl + 2 NaOH \rightarrow N_2H_4 + H_2O + NaCl + Na_2CO_3\]

\[ \rm 2 NH_3 + H_2O_2 \rightarrow N_2H_4 + 2 H_2O\]

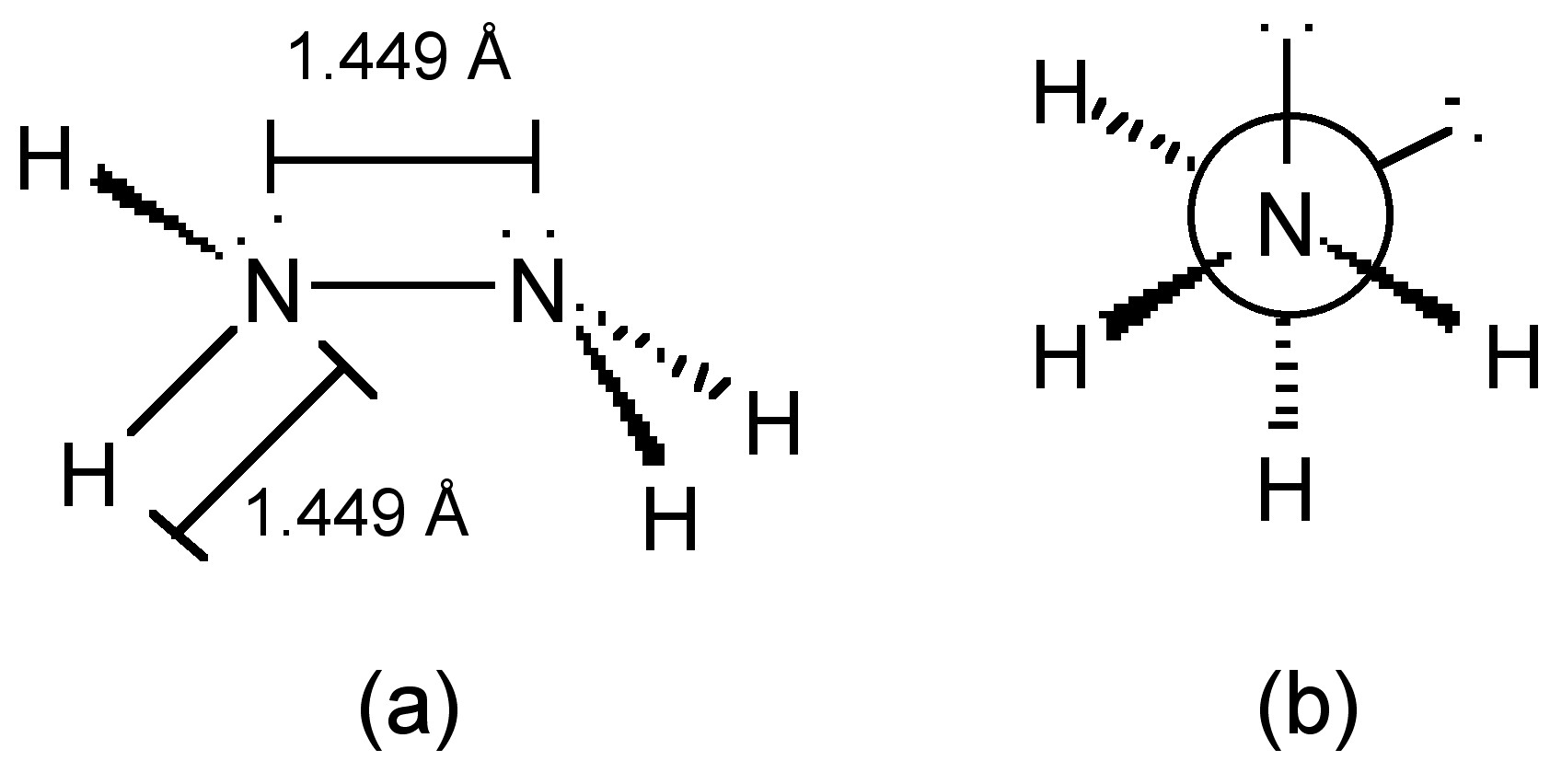

Structure

The nitrogen atoms in hydrazine adopt sp3 hybridization (Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\)a), and molecule adopts a gauche conformation in the vapor, liquid and solid states (Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\)b).

In a similar manner to ammonia, (8.3.42), hydrazine is a self-ionizing, (8.3.43). While there is a wide range of salts of the N2H5+ cation, only the sodium and potassium salts of N2H3- are stable.

\[ \rm 2 NH_3 \rightleftharpoons \underset{ammonium}{NH_4^+} + \underset{amide}{NH_2^-}\]

\[ \rm 2 N_2H_4 \rightleftharpoons N_2H_5^+ + N_2H_3^-\]

Reaction chemistry and uses

Hydrazine is polar, highly ionizing, and forms stable hydrogen bonds, and its resemblance to water is reflected in the formation of aqueous solutions and hydrates. In the solid state the monohydrate is formed, i.e., N2H4.H2O. In solution hydrazine acts as a base to form the hydrazinium ion, (8.3.44) where Kb = 8.5 x 10-7. The presence of a second Lewis base site means that hydrazine can be protonated twice to form the hydrazonium ion, (8.3.45) where Kb = 8.9 x 10-16. Salts of the cation N2H5+ are stable in water; however, the salts of the dication are less stable.

\[ \rm 2 NH_3 \rightleftharpoons NH_4^+ + NH_2^-\]

\[ \rm N_2H_5^+ + H_2O \rightleftharpoons N_2H_5^{2+} + OH^-\]

The reaction of hydrazine with oxygen is highly favored, (8.3.46), and the explosive limit is 1.8 – 100 vol%.

\[ \rm N_2H_4 + O_2 \rightarrow N_2 + 2 H_2O \]

Hydrazine is useful in a number of organic reactions for the synthesis of a wide range of compounds used in pharmaceuticals, textile dyes, and in photography, including:

- Hydrazone formation, (8.3.47) and (8.3.48).

- Alkyl-substituted hydrazine synthesis via direct alkylation with alkyl halides.

- Reaction with 2-cyanopyridines to form amide hydrazides, which can be converted using 1,2-diketones into triazines.

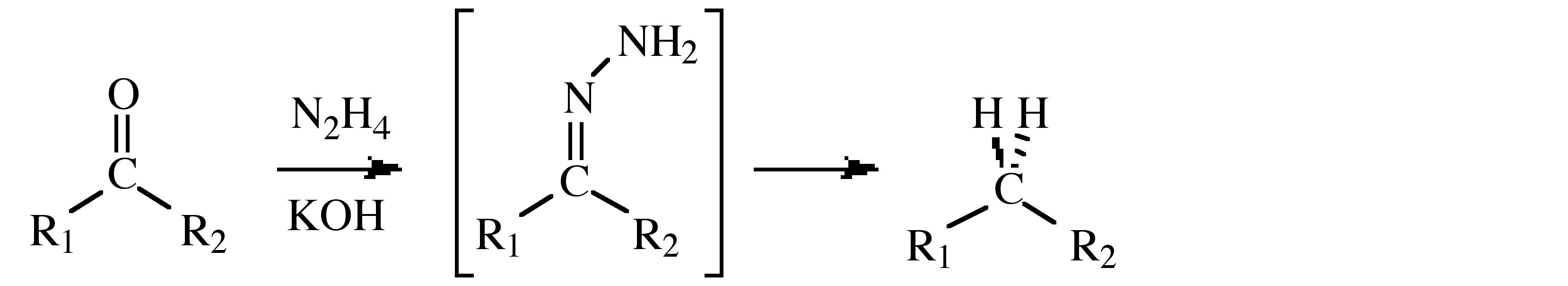

- Use in the Wolff-Kishner reduction that transforms the carbonyl group of a ketone or aldehyde into a methylene (or methyl) group via a hydrazone intermediate, (shown below).

- As a building block for the preparation of many heterocyclic compounds via condensation with a range of difunctional electrophiles.

- Cleavage N-alkylated phthalimide derivatives.

- As a convenient reductant because the by-products are typically nitrogen gas and water.

\[ \rm 2 (CH_3)_2\text{C=O} + N_2H_4 \rightarrow 2 H_2O + [(CH_3)_2\text{C=N}]_2\]

\[ \rm [(CH_3)_2\text{C=N}]_2 + N_2H_4 \rightarrow 2 (CH_3)+2\text{C=N}NH_2\]

Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet

Designed by Alexander Lippisch (Figure \(\PageIndex{18}\)), the Messerschmitt Me 163B Komet (Figure \(\PageIndex{19}\)) was the first rocket-powered fighter plane. With a top speed of around 596 mph (Mach 0.83) and a service ceiling of 40,000 ft, the Komet’s performance of the Me 163B far exceeded that of contemporary piston engine fighters. However, despite its impressive performance, it was only produced in limited numbers (ca. 370 as compared to the 1,430 built of its jet powered compatriot the Me 262) and was not an effective combat airplane.

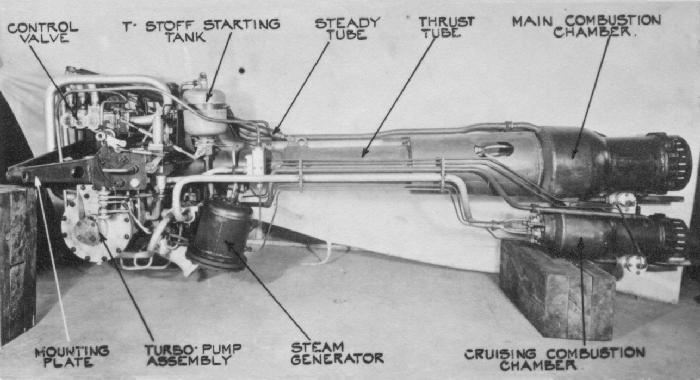

The Komet was powered by the HWK 109-509 hot engine (Figure \(\PageIndex{20}\)) that used a mixture of a fuel and an oxidizer. The fuel was a mixture of hydrazine hydrate (30%), methanol (57%), and water (13%) that was designated by the code name, C-Stoff, that burned with the oxygen-rich exhaust from hydrogen peroxide (T-Stoff) used as the oxidizer. The C-Stoff was stored in a glass tank on the plane, while the T-Stoff was stored in an aluminum container. An oxidizing agent cocktail of CaMnO4 and/or K2CrO4 was added to the T-Stoff generating steam and high temperatures, this in tern reacted violently with the C-Stoff. The flow of reagents was controlled by two pumps, to regulate the rate of combustion and thereby the amount of thrust. The violent combustion process resulted in the formation of water, carbon dioxide and nitrogen, and a huge amount of heat sending out a superheated stream of steam, nitrogen and air that was drawn in through the hole in the mantle of the engine, thus providing a forward thrust of approximately 3,800 lbf. Because of the potential hazards of mixing the fuels, they were stored at least 1/2 mile apart, and the plane was washed with water between fueling steps and after missions.

Phosphine and Arsine

Because of their use in metal organic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD) of 13-15 (III-V) semiconductor compounds phosphine (PH3) and arsine (AsH3) are prepared on an industrial scale.

Synthesis

Phosphine (PH3) is prepared by the reaction of elemental phosphorus (P4) with water, (8.3.49). Ultra pure phosphine that is used by the electronics industry is prepared by the thermal disproportionation of phosphorous acid, (8.3.50).

\[ \rm 2 P_4 + 12 H_2O \rightarrow 5 PH_3 + 3 H_3PO_4\]

\[ \rm 4 H_3PO_4 \rightarrow PH_3 + 3 H_3PO_4\]

Arsine can be prepared by the reduction of the chloride, (8.3.51) or (8.3.52). The corresponding syntheses can also be used for stibine and bismuthine.

\[ \rm 4 AsCl_3 + 3 LiAlH_4 \rightarrow 4 AsH_3 + 3 LiAlCl_4\]

\[ \rm 4 AsCl_3 + 3 NaBH_4 \rightarrow 4 AsH_3 + 3 NaCl + 3 BCl_3\]

The hydrolysis of calcium phosphide or arsenide can also generate the trihydrides.

Structure

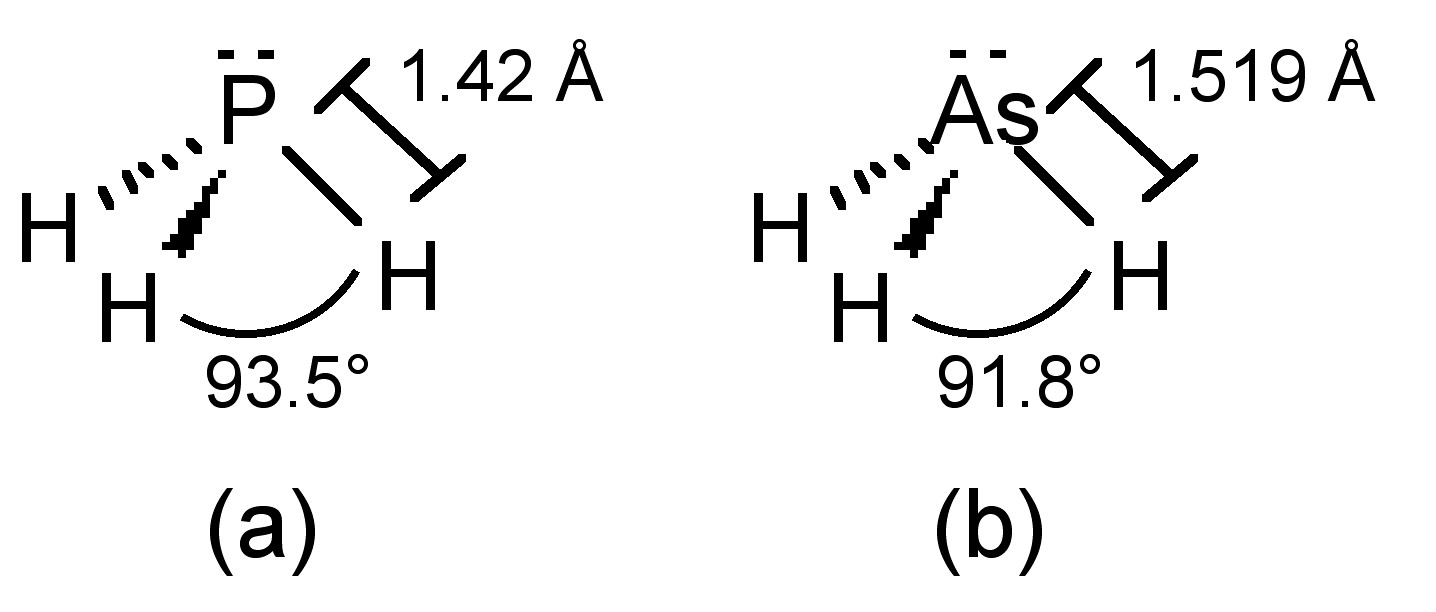

The phosphorus in phosphine adopts sp3 hybridization, and thus phosphine has an umbrella structure (Figure \(\PageIndex{21}\)a) due to the stereochemically active lone pair. The barrier to inversion of the umbrella (Ea = 155 kJ/mol) is much higher than that in ammonia (Ea = 24 kJ/mol). Putting this difference in context, ammonia’s inversion rate is 1011 while that of phosphine is 103. As a consequence it is possible to isolate chiral organophosphines (PRR'R"). Arsine adopts the analogous structure (Figure \(\PageIndex{21}\)b).

Reactions

Phosphine is only slightly soluble in water (31.2 mg/100 mL) but it is readily soluble in non-polar solvents. Phosphine acts as neither an acid nor a base in water; however, proton exchange proceeds via the phosphonium ion (PH4+) in acidic solutions and via PH2- at high pH, with equilibrium constants Kb = 4 x 10-28 and Ka = 41.6 x 10-29, respectively.

Arsine has similar solubility in water to that of phosphine (i.e., 70 mg/100 mL), and AsH3 is generally considered non-basic, but it can be protonated by superacids to give isolable salts of AsH4+. Arsine is readily oxidized in air, (8.3.53).

\[ \rm 2 AsH_3 + 3 O_2 \rightarrow As_2O_3 + 3 H_2O\]

Arsine will react violently in presence of strong oxidizing agents, such as potassium permanganate, sodium hypochlorite or nitric acid. Arsine decomposes to its constituent elements upon heating to 250 - 300 °C.

Gutzeit test

The Gutzeit test is the characteristic test for arsenic and involves the reaction of arsine with Ag+. Arsine is generated by reduction of aqueous arsenic compounds, typically arsenites, with Zn in the presence of H2SO4. The evolved gaseous AsH3 is then exposed to silver nitrate either as powder or as a solution. With solid AgNO3, AsH3 reacts to produce yellow Ag4AsNO3, while with a solution of AgNO3 black Ag3As is formed.

Hazards

Pure phosphine is odorless, but technical grade phosphine has a highly unpleasant odor like garlic or rotting fish, due to the presence of substituted phosphine and diphosphine (P2H4). The presence of P2H4 also causes spontaneous combustion in air. Phosphine is highly toxic; symptoms include pain in the chest, a sensation of coldness, vertigo, shortness of breath, and at higher concentrations lung damage, convulsions and death. The recommended limit (RL) is 0.3 ppm.

Arsine is a colorless odorless gas that is highly toxic by inhalation. Owing to oxidation by air it is possible to smell a slight, garlic-like scent when arsine is present at about 0.5 ppm. Arsine attacks hemoglobin in the red blood cells, causing them to be destroyed by the body. Further damage is caused to the kidney and liver. Exposure to arsine concentrations of 250 ppm is rapidly fatal: concentrations of 25 – 30 ppm are fatal for 30 min exposure, and concentrations of 10 ppm can be fatal at longer exposure times. Symptoms of poisoning appear after exposure to concentrations of 0.5 ppm and the recommended limit (RL) is as low as 0.05 ppm.

Bibliography

- R. Minkwitz, A. Kornath, W. Sawodny, and H. Härtner, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem., 1994, 620, 753.