6.7: Boron Oxides, Hydroxides, and Oxyanions

- Page ID

- 212883

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Oxides

Boron oxide, B2O3, is made by the dehydration of boric acid, (6.7.1). It is a glassy solid with no regular structure, but can be crystallized with extreme difficulty. The structure consists of infinite chains of triangular BO3 unit (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). Boron oxide is acidic and reacts with water to reform boric acid, (6.7.1).

\[\text{2 B(OH)}_3 \xrightleftharpoons{\Delta} \text{B}_2\text{O}_3 \text{ + H}_2\text{O}\]

The reaction of B2O3 with hydroxide yields the metaborate ion, (6.7.2), whose planar structure (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)) is related to metaboric acid. Boron oxide fuses with a wide range of metal and non-metal oxides to give borate glasses.

\[\text{B}_2\text{O}_3\text{ + 6 KOH} \rightarrow \text{2 K}_3\text{[B}_3\text{O}_6\text{] + 3 H}_2\text{O}\]

Boric acid

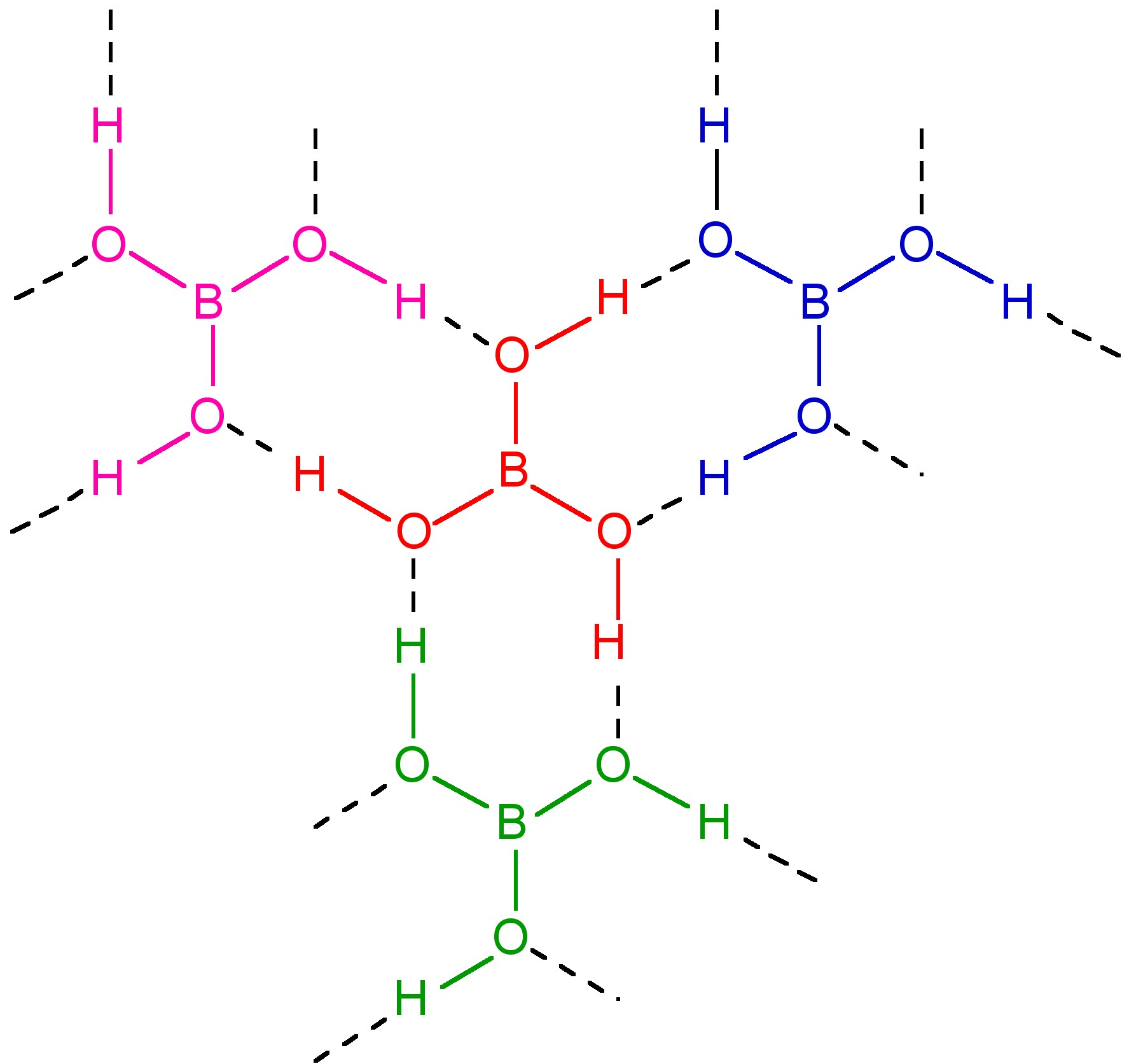

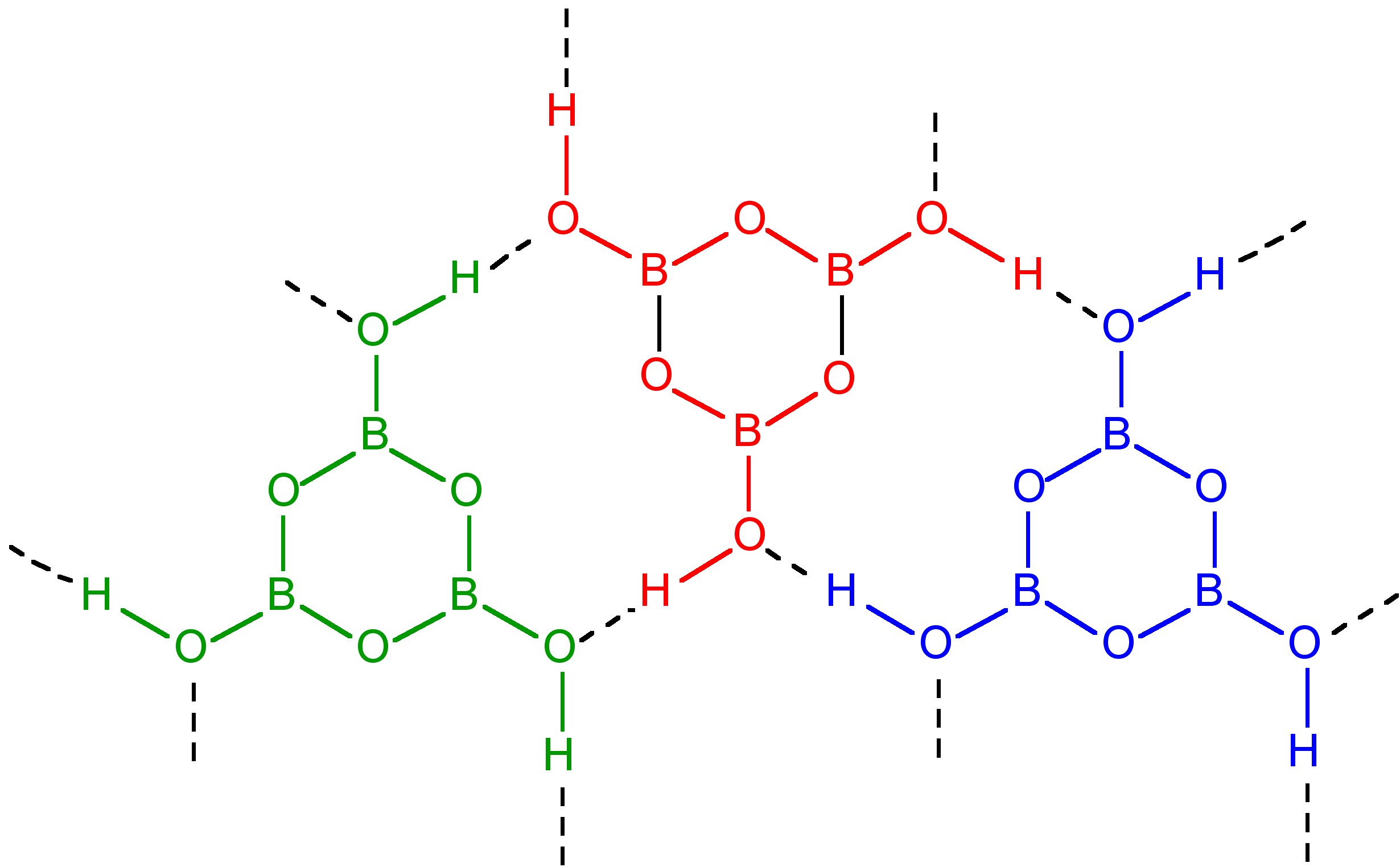

Boric acid, B(OH)3, usually obtained from the dissolution of borax, Na2[B4O5(OH)4], is a planar solid with intermolecular hydrogen bonding forming a near hexagonal layered structure, broadly similar to graphite (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). The inter layer distance is 3.18 Å.

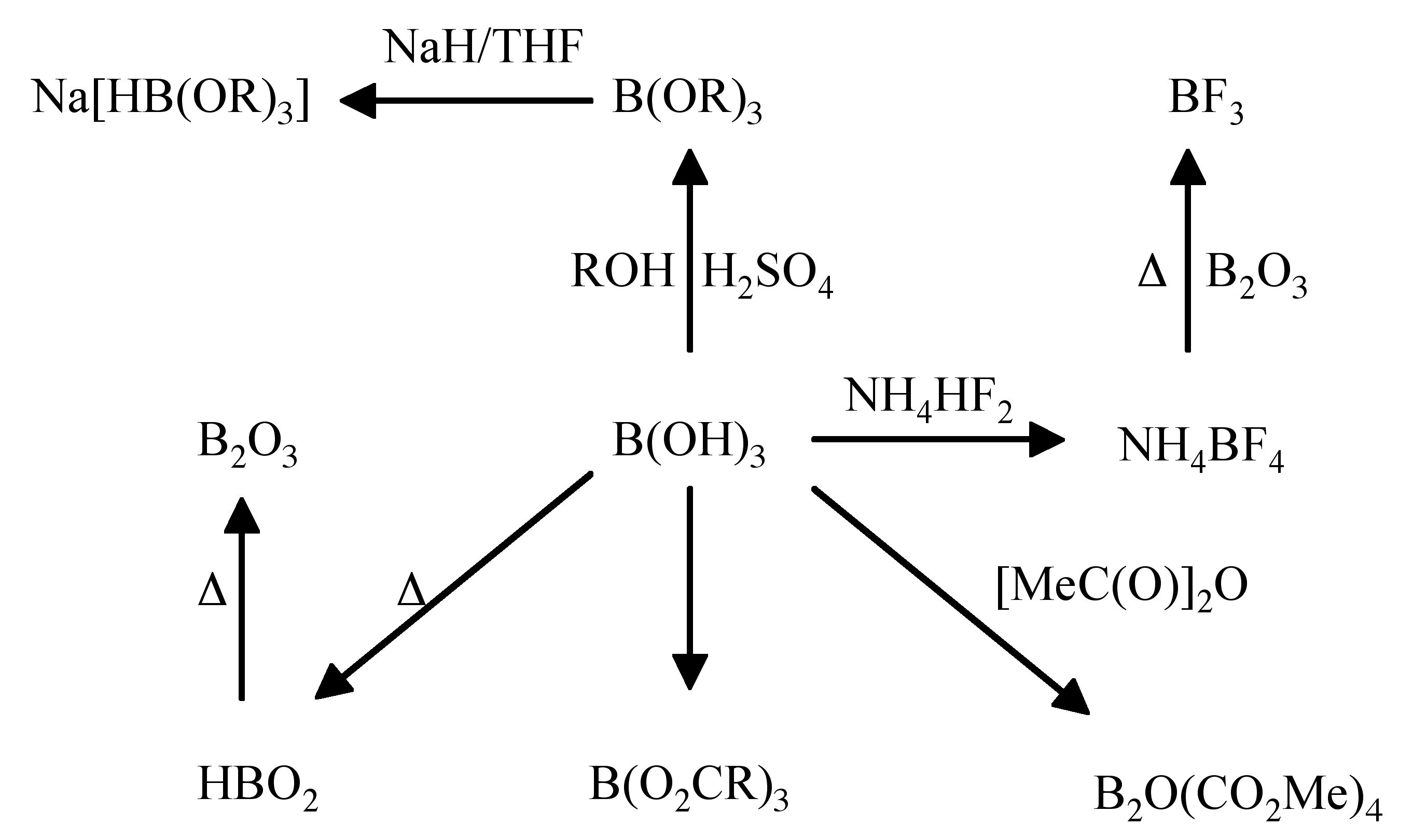

A summary of reactions of the reactivity of boric acid is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\).

Upon dissolution of boric acid in water, boric acid does not act as a proton acid, but instead reacts as a Lewis acid, (6.7.3).

\[\text{B(OH)}_3 \text{ + 2 H}_2\text{O} \rightleftharpoons \text{B(OH)}_4^- \text{ + H}_3\text{O}^+ \]

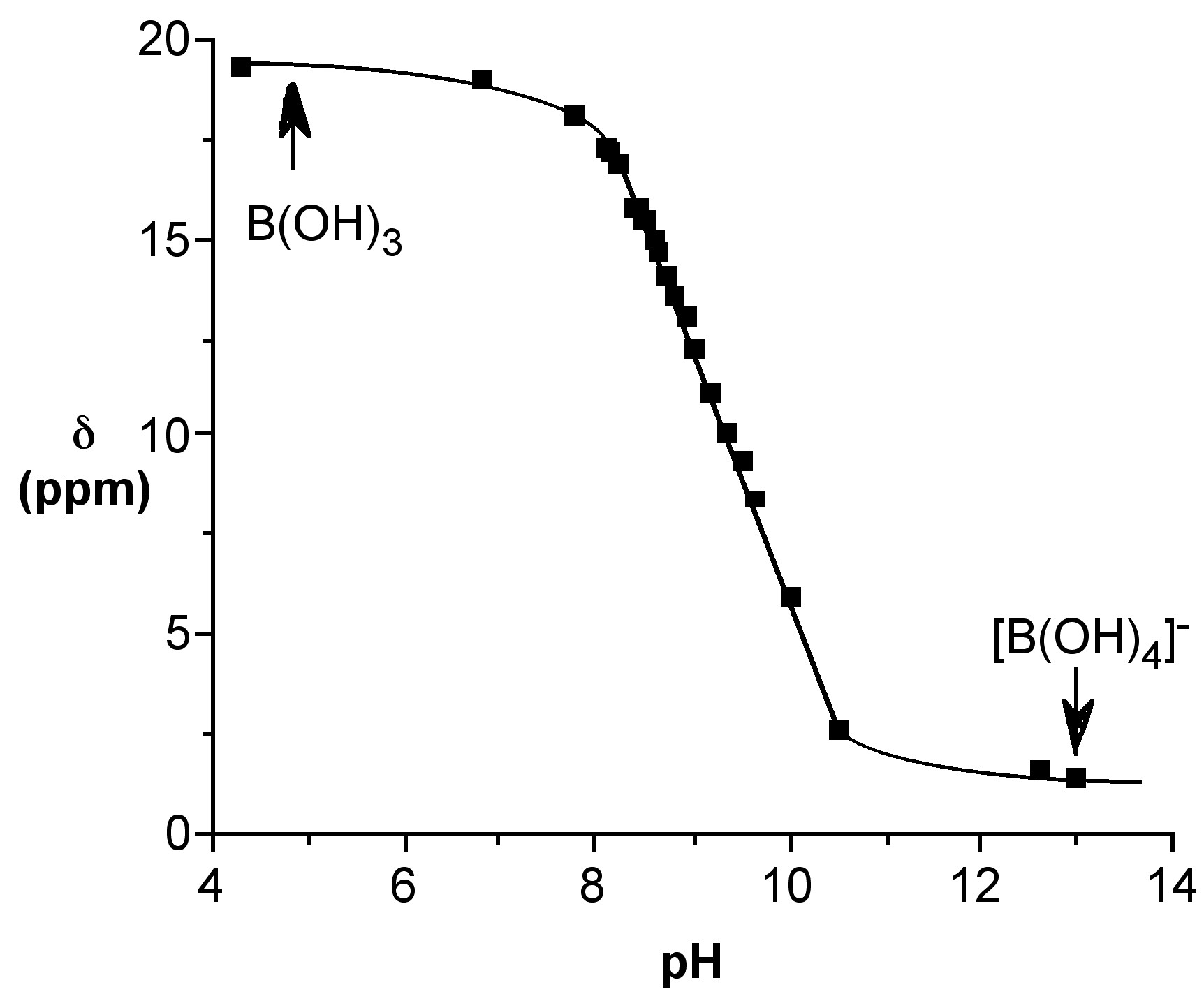

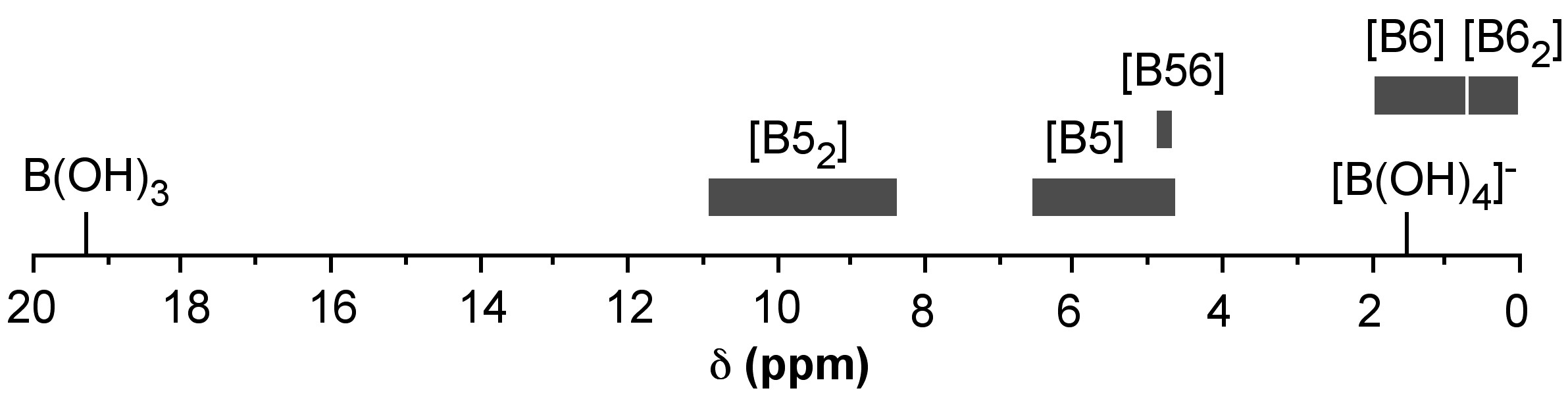

The reaction may be followed by 11B NMR spectroscopy from the change in the chemical shift (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)).

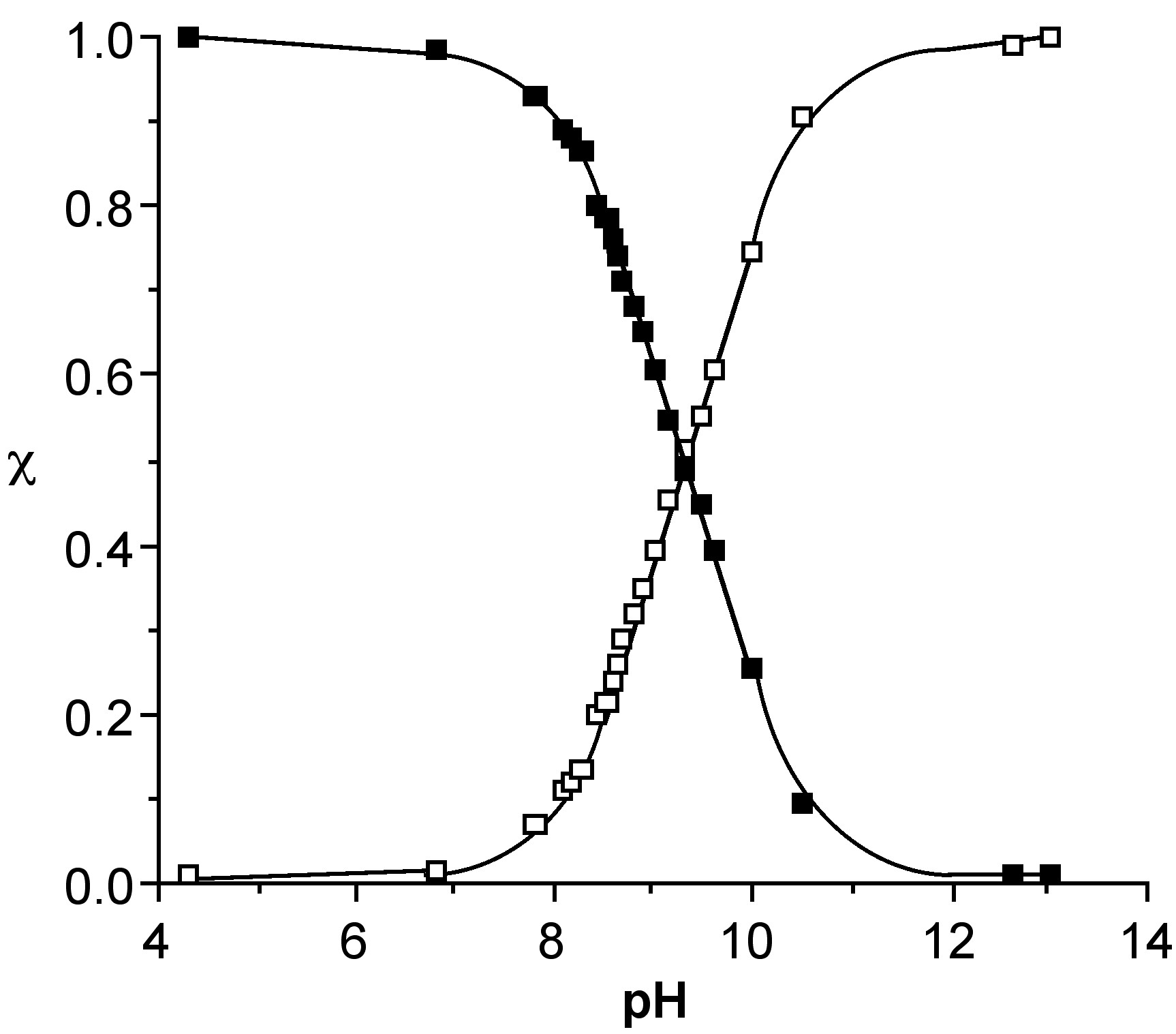

Since the 11B NMR shift is directly proportional to the mole fraction of the total species present as the borate anion (e.g., [B(OH)4]-) the 11B NMR chemical shift at a given temperature, δ(obs), may be used to calculate both the mole fraction of boric acid and the borate anion, i.e., (6.7.4) and (6.7.5), respectively. Using these equations the relative speciation as a function of pH may be calculated for both boric acid (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)). The pH at which a 50:50 mixture of acid and anion for boric acid is ca. 9.4.

\[ \chi_{\text{(acid)}} = \dfrac{\delta_{\text{(obs)}} - \delta_{\text{(anion)}}}{\delta_{\text{(acid)}} - \delta_{\text{(anion)}}}\]

\[ \chi_{\text{(acid)}} = \dfrac{\delta_{\text{(acid)}} - \delta_{\text{(obs)}}}{\delta_{\text{(acid)}} - \delta_{\text{(anion)}}}\]

In concentrated solutions, the borate ion reacts further to form polyborate ions. The identity of the polyborate is dependent on the pH. With increasing pH, B5O6(OH)4-, (6.7.5), B3O3(OH)4-, (6.7.6), and B4O5(OH)42-, (6.7.7), are formed. The structure of each borate is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\). Once the ratio of B(OH)3 to B(OH)4- is greater than 50%, only the mono-borate is observed.

\[ \text{4 B(OH)}_3 \text{ + B(OH)}^-_4 \rightleftharpoons \text{B}_5\text{O}_6\text{(OH)}_4^- \text{ + 6 H}_2\text{O}\]

\[ \text{4 B(OH)}_3 \text{ + B(OH)}^-_4 \rightleftharpoons \text{B}_3\text{O}_3\text{(OH)}_4^- \text{ + 3 H}_2\text{O} \]

\[ \text{2 B(OH)}_3 \text{ + 2 B(OH)}^-_4 \rightleftharpoons \text{B}_4\text{O}_5\text{(OH)}_4^{2-} \text{ + 5 H}_2\text{O} \]

Borax, the usual mineral form of boric acid, is the sodium salt, Na2[B4O5(OH)4], which upon dissolution in water re-equilibrates to B(OH)3.

Enough to make your hair curl

In 1906, a German hairdresser, Charles Nessler who was living in London, decided to help his sister who was fed-up with having to put her straight hair in curlers. While looking for a solution, Nessler noticed that a clothesline contracted in a wavy shape when it was wet. Nessler wound his sister’s hair on cardboard tubes; then he covered the hair with borax paste. After wrapping the tubes with paper (to exclude air) he heated the entire mass for several hours. Removing the paper and tubes resulted in curly hair. After much trial and error (presumably at his sisters discomfort) Nessler perfected the method by 1911, and called the process a permanent wave (or perm). The process involved the alkaline borax softening the hair sufficiently to be remodeled, while the heating stiffened the borax to hold the hair into shape. The low cost of borax meant that Nessler’s methods was an immediate success.

Metaboric acid

Heating boric acid results in the partial dehydration to yield metaboric acid, HBO2, (6.7.8). Metaboric acid is also formed from the partial hydrolysis of B2O3.

\[ \text{B(OH)}_3 \xrightleftharpoons[\text{H}_2\text{O}]{\Delta} \text{HBO}_2 \xrightleftharpoons[\text{H}_2\text{O}]{\Delta} \text{B}_2\text{O}_3 \]

If the heating is carried out below 130 °C, HBO2-III is formed in which B3O3 rings are joined by hydrogen bonding to the hydroxide on each boron atom (Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)). Continued heating to 150 °C results in HBO2-II, whose structure consists of BO4 tetrahedra and B2O5 groups chain linked by hydrogen bonding. Finally, heating above 150 °C yields cubic HBO2-I with all the boron atoms tetrahedral.

Borate esters

Boric acid reacts with alcohols in the presence of sulfuric acid to form B(OR)3 (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). This is the basis for a simple flame test for boron. Treatment of a compounds with methanol/sulfuric acid, followed by placing the reaction product in a flame results in a green flame due to B(OMe)3.

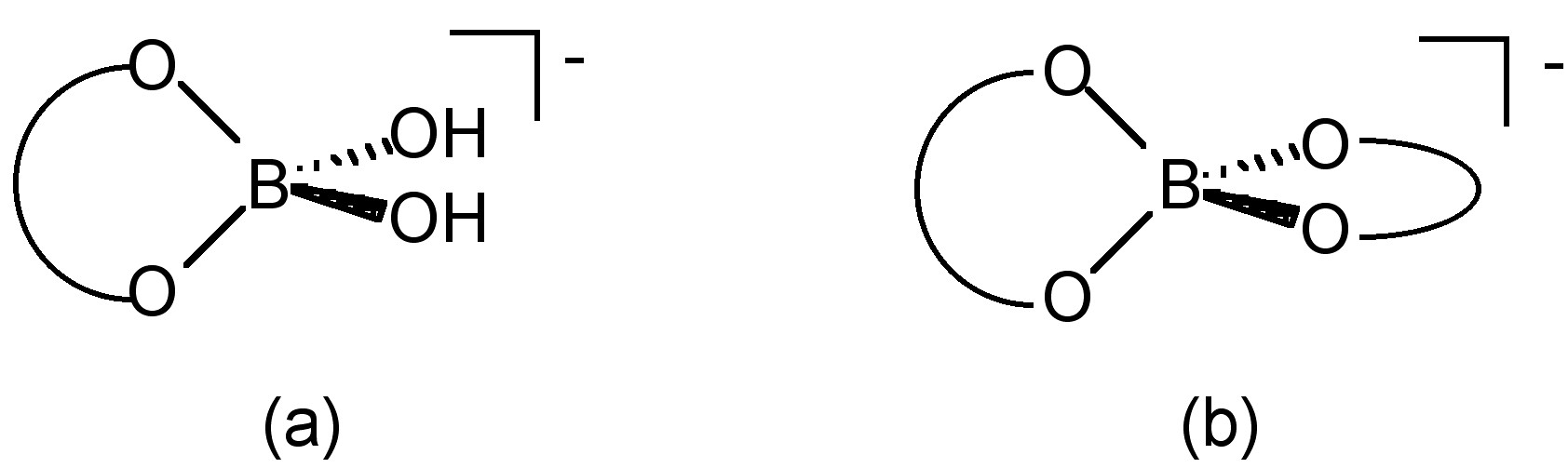

In the presence of diols, polyols, or polysaccharides, boric acid reacts to form alkoxide complexes. In the case of diols, the mono-diol [B(OH)2L]- (Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)a) and the bis-diol [BL2]- (Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)b) complexes.

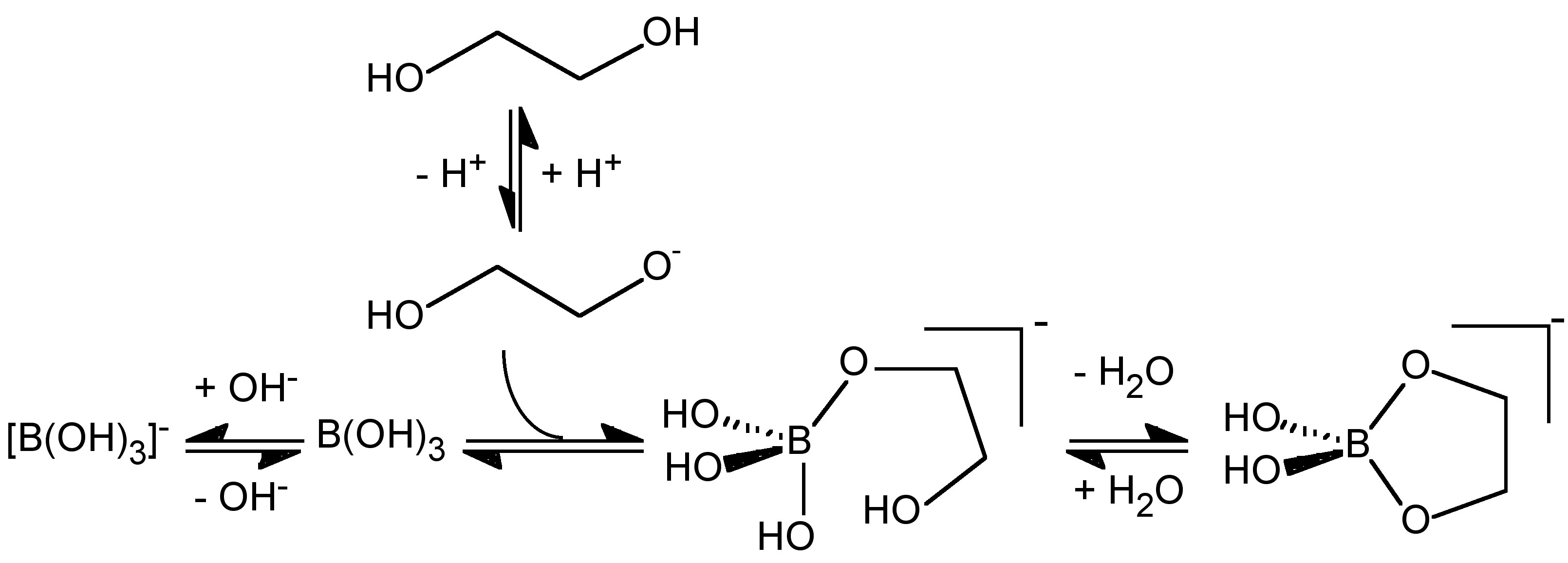

Originally it was proposed that diols react with the anion rather than boric acid, (6.7.9). In contrast, it was suggested that the optimum pH for the formation of carboxylic acid complexes is under the condition where pKa (carboxylic acid) < pH < pKa (boric acid). Under these conditions it is the boric acid, B(OH)3, not the borate anion, [B(OH)4]-, that reacts to form the complex.

\[ \text{[B(OH)}_4\text{]}^- \xrightleftharpoons{\text{+ LH}_2} \text{[B(OH)}_2\text{L]}^- \xrightleftharpoons{\text{+ LH}_2} \text{[BL}_2\text{]}^-\]

The conversion of boric acid to borate (6.7.3) must occur through attack of hydroxide or the deprotonation of a coordinated water ligand, either of which is related to the pKa of water. The formation of [B(OH)2L]- from B(OH)3 would be expected therefore to occur via a similar initial reaction (attack by RO- or deprotonation of coordinated ROH) followed by a subsequent elimination of H2O and the formation of a chelate coordination, and would therefore be related to the pKa of the alcohol. Thus the pH at which [B(OH)2L]- is formed relative to [B(OH)4]- will depend on the relative acidity of the alcohol. The pKa of a simple alcohol (e.g., MeOH = 15.5, EtOH = 15.9) are close to the value for water (15.7) and the lowest pH at which [B(OH)2L]- is formed should be comparable to that at which [B(OH)4]- forms. Thus, the formation of [B(OH)2L]- as compared to [B(OH)4]- is a competition between the reaction of B(OH)3 with RO- and OH- (Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\)), and as with carboxylic acids it is boric acid not borate that reacts with the alcohol, (6.7.10).

\[ \text{B(OH)}_3 \xrightleftharpoons{\text{+ LH}_2} \text{[B(OH)}_2\text{L]}^- \xrightleftharpoons{\text{+ LH}_2} \text{[BL}_2\text{]}^- \]

A key issue in the structural characterization and understanding of the diol/boric acid system is the assignment of the 11B NMR spectral shifts associated with various complexes. A graphical representation of the observed shift ranges for boric acid chelate systems is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\).

Boric acid cross-linking of guar gum for hydraulic fracturing fluids

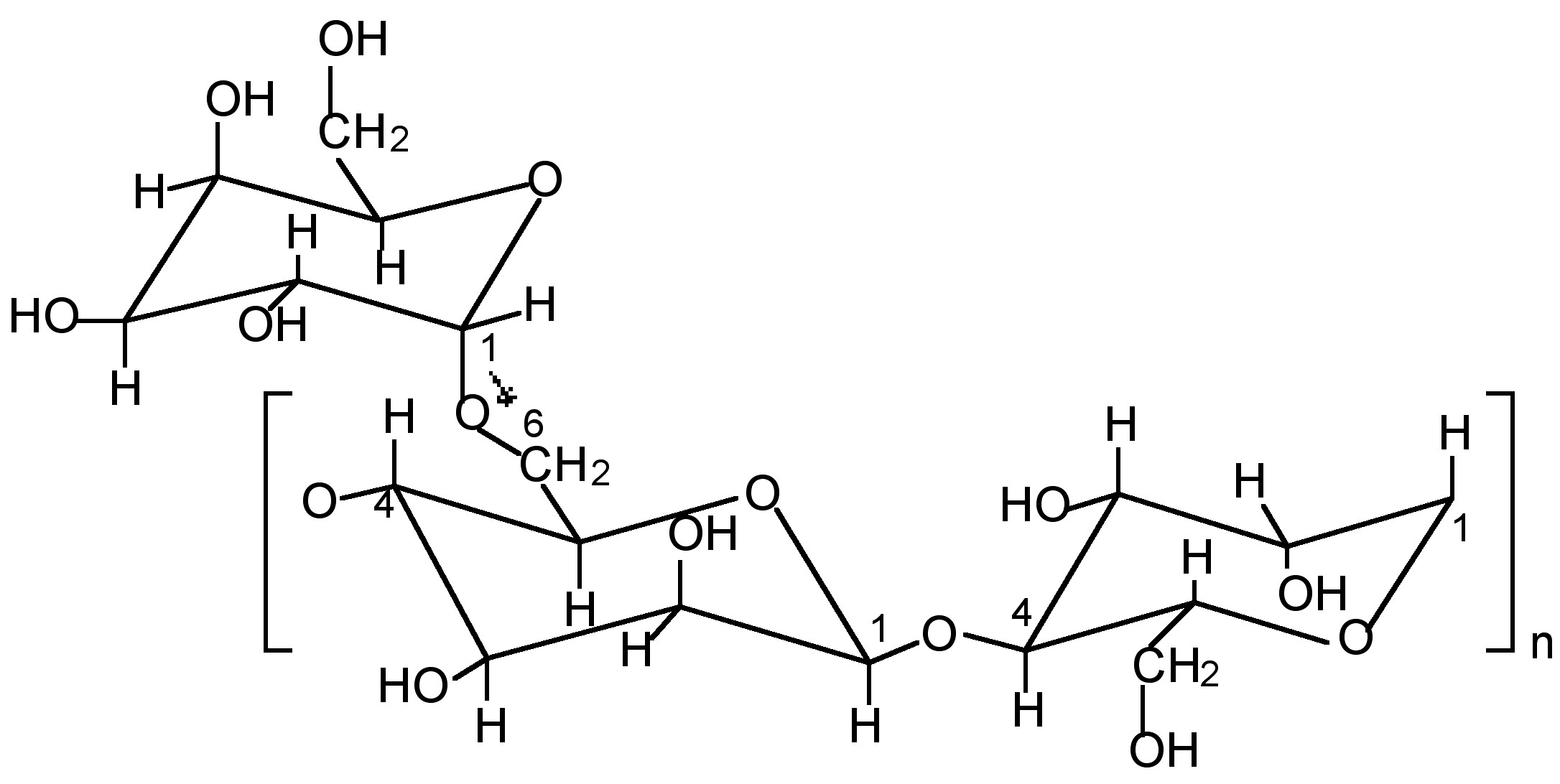

Thick gels of guar gum cross-linked with borax or a transition metal complex are used in the oil well drilling industry as hydraulic fracturing fluids. The polysaccharide guaran (Mw ≈ 106 Da) is the major (>85 wt%) component of guar gum, and consists of a (1→4)-β-D-mannopyranosyl backbone with α-D-galactopyranosyl side chain units attached via (1→6) linkages. Although the exact ratio varies between different crops of guar gum the general structure is consistent with about one galactose to every other mannose (Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\)).

The synthesis of a typical boric acid cross-linked guar gel, with viscosity properties suitable for use as a fracturing fluid, involves mixing guar gum, water and boric acid, B(OH)3, in a 10:2000:1 wt/wt ratio. Adjusting the pH to between 8.5 and 9 results in a viscous gel. The boron:guaran ratio corresponds to almost 2 boron centers per 3 monosaccharide repeat units. Such a large excess of boric acid clearly indicates that the system is not optimized for cross-linking, i.e., a significant fraction of the boric acid is ineffective as a cross-linking agent.

The reasons for the inefficiency of boric acid to cross-link guaran (almost 2 borate ions per 3 monosaccharide repeat unit are required for a viscous gel suitable as a fracturing fluid): the most reactive sites on the component saccharides (mannose and galactose) are precluded from reaction by the nature of the guar structure; the comparable acidity (pKa) of the remaining guaran alcohol substituents and the water solvent, results in a competition between cross-linking and borate formation; a significant fraction of the boric acid is ineffective in cross-linking guar due to the modest equilibrium (Keq).

Bibliography

- F. A. Cotton and G. Wilkinson, Advanced Inorganic Chemistry, 4th Ed. Wiley Interscience (1980).

- M. Bishop, N. Shahid, J. Yang, and A. R. Barron, Dalton Trans., 2004, 2621.

- M. Van Duin, J. A. Peters, A. P. G. Kieboom, and H. Van Bekkum, Tetrahedron, 1984, 40, 2901.

- Zonal Isolation, “Borate Crosslinked Fluids,” by R. J. Powell and J. M Terracina, Halliburton, Duncan, OK (1998).

- R. Schechter, Oil Well Stimulation, Prentice-Hall Inc., Englewood Cliffs, NJ (1992).

- S. Kesavan and R. K. Prud'homme, Macromolecules, 1992, 25, 2026.