2.1: Early Ideas in Atomic Theory

- Page ID

- 78710

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Skills to Develop

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- State the postulates of Dalton’s atomic theory

- Use postulates of Dalton’s atomic theory to explain the laws of definite and multiple proportions

The language used in chemistry is seen and heard in many disciplines, ranging from medicine to engineering to forensics to art. The language of chemistry includes its own vocabulary as well as its own form of shorthand. Chemical symbols are used to represent atoms and elements. Chemical formulas depict molecules as well as the composition of compounds. Chemical equations provide information about the quality and quantity of the changes associated with chemical reactions.

This chapter will lay the foundation for our study of the language of chemistry. The concepts of this foundation include the atomic theory, the composition and mass of an atom, the variability of the composition of isotopes, ion formation, chemical bonds in ionic and covalent compounds, the types of chemical reactions, and the naming of compounds. We will also introduce one of the most powerful tools for organizing chemical knowledge: the periodic table.

Atomic Theory through the Nineteenth Century

The earliest recorded discussion of the basic structure of matter comes from ancient Greek philosophers, the scientists of their day. In the fifth century BC, Leucippus and Democritus argued that all matter was composed of small, finite particles that they called atomos, a term derived from the Greek word for “indivisible.” They thought of atoms as moving particles that differed in shape and size, and which could join together. Later, Aristotle and others came to the conclusion that matter consisted of various combinations of the four “elements”—fire, earth, air, and water—and could be infinitely divided. Interestingly, these philosophers thought about atoms and “elements” as philosophical concepts, but apparently never considered performing experiments to test their ideas.

The Aristotelian view of the composition of matter held sway for over two thousand years, until English schoolteacher John Dalton helped to revolutionize chemistry with his hypothesis that the behavior of matter could be explained using an atomic theory. First published in 1807, many of Dalton’s hypotheses about the microscopic features of matter are still valid in modern atomic theory. Here are the postulates of Dalton’s atomic theory.

- Matter is composed of exceedingly small particles called atoms. An atom is the smallest unit of an element that can participate in a chemical change.

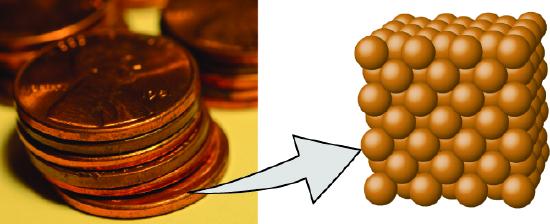

- An element consists of only one type of atom, which has a mass that is characteristic of the element and is the same for all atoms of that element (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). A macroscopic sample of an element contains an incredibly large number of atoms, all of which have identical chemical properties.

- Atoms of one element differ in properties from atoms of all other elements.

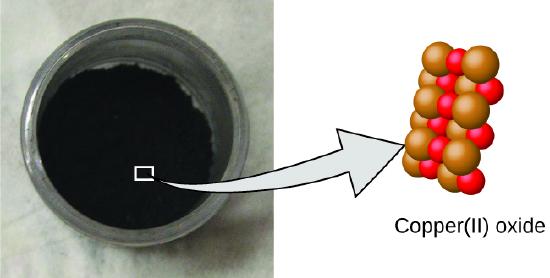

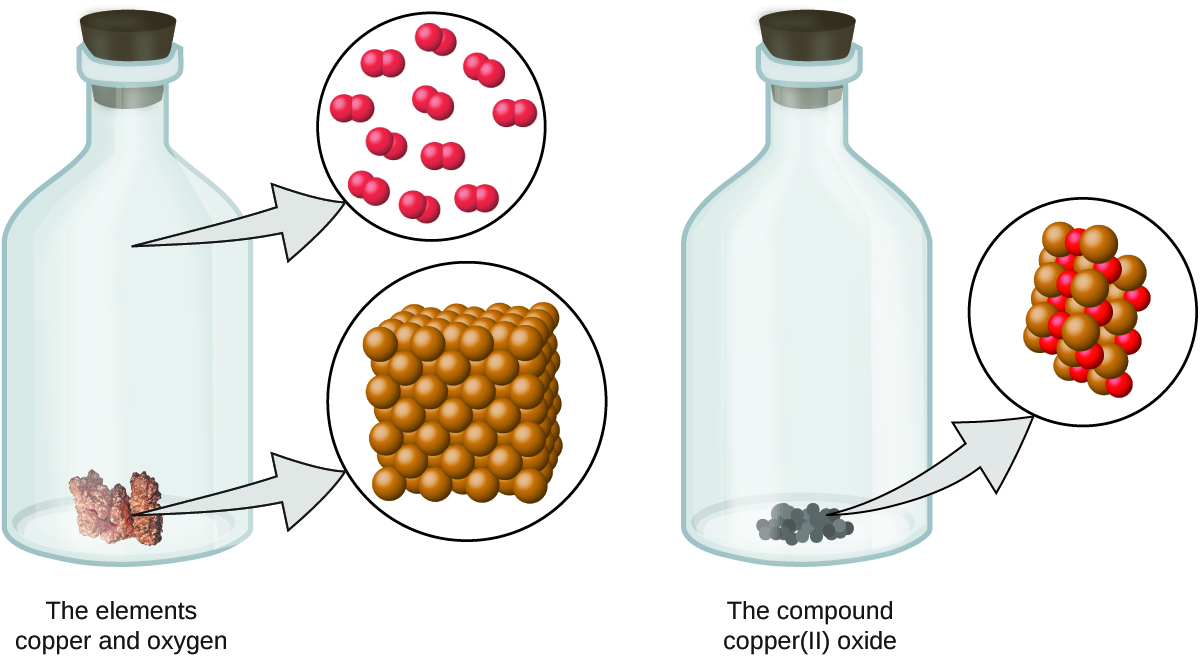

- A compound consists of atoms of two or more elements combined in a small, whole-number ratio. In a given compound, the numbers of atoms of each of its elements are always present in the same ratio (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)).

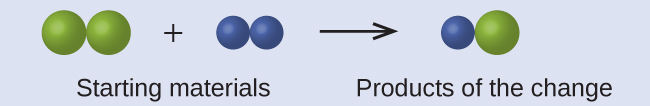

- Atoms are neither created nor destroyed during a chemical change, but are instead rearranged to yield substances that are different from those present before the change (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)).

Dalton’s atomic theory provides a microscopic explanation of the many macroscopic properties of matter that you’ve learned about. For example, if an element such as copper consists of only one kind of atom, then it cannot be broken down into simpler substances, that is, into substances composed of fewer types of atoms. And if atoms are neither created nor destroyed during a chemical change, then the total mass of matter present when matter changes from one type to another will remain constant (the law of conservation of matter).

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Testing Dalton’s Atomic Theory

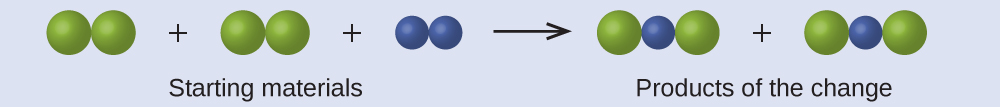

In the following drawing, the green spheres represent atoms of a certain element. The purple spheres represent atoms of another element. If the spheres touch, they are part of a single unit of a compound. Does the following chemical change represented by these symbols violate any of the ideas of Dalton’s atomic theory? If so, which one?

Solution The starting materials consist of two green spheres and two purple spheres. The products consist of only one green sphere and one purple sphere. This violates Dalton’s postulate that atoms are neither created nor destroyed during a chemical change, but are merely redistributed. (In this case, atoms appear to have been destroyed.)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

In the following drawing, the green spheres represent atoms of a certain element. The purple spheres represent atoms of another element. If the spheres touch, they are part of a single unit of a compound. Does the following chemical change represented by these symbols violate any of the ideas of Dalton’s atomic theory? If so, which one

Answer:

The starting materials consist of four green spheres and two purple spheres. The products consist of four green spheres and two purple spheres. This does not violate any of Dalton’s postulates: Atoms are neither created nor destroyed, but are redistributed in small, whole-number ratios.

Dalton knew of the experiments of French chemist Joseph Proust, who demonstrated that all samples of a pure compound contain the same elements in the same proportion by mass. This statement is known as the law of definite proportions or the law of constant composition. The suggestion that the numbers of atoms of the elements in a given compound always exist in the same ratio is consistent with these observations. For example, when different samples of isooctane (a component of gasoline and one of the standards used in the octane rating system) are analyzed, they are found to have a carbon-to-hydrogen mass ratio of 5.33:1, as shown in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\).

| Sample | Carbon | Hydrogen | Mass Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 14.82 g | 2.78 g | \(\mathrm{\dfrac{14.82\: g\: carbon}{2.78\: g\: hydrogen}=\dfrac{5.33\: g\: carbon}{1.00\: g\: hydrogen}}\) |

| B | 22.33 g | 4.19 g | \(\mathrm{\dfrac{22.33\: g\: carbon}{4.19\: g\: hydrogen}=\dfrac{5.33\: g\: carbon}{1.00\: g\: hydrogen}}\) |

| C | 19.40 g | 3.64 g | \(\mathrm{\dfrac{19.40\: g\: carbon}{3.63\: g\: hydrogen}=\dfrac{5.33\: g\: carbon}{1.00\: g\: hydrogen}}\) |

It is worth noting that although all samples of a particular compound have the same mass ratio, the converse is not true in general. That is, samples that have the same mass ratio are not necessarily the same substance. For example, there are many compounds other than isooctane that also have a carbon-to-hydrogen mass ratio of 5.33:1.00.

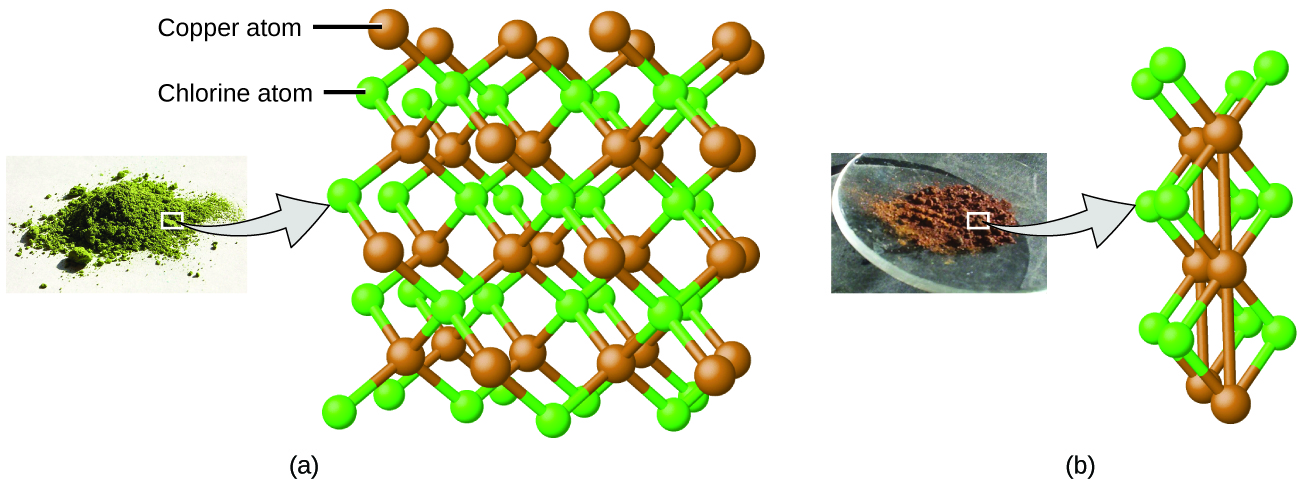

Dalton also used data from Proust, as well as results from his own experiments, to formulate another interesting law. The law of multiple proportions states that when two elements react to form more than one compound, a fixed mass of one element will react with masses of the other element in a ratio of small, whole numbers. For example, copper and chlorine can form a green, crystalline solid with a mass ratio of 0.558 g chlorine to 1 g copper, as well as a brown crystalline solid with a mass ratio of 1.116 g chlorine to 1 g copper. These ratios by themselves may not seem particularly interesting or informative; however, if we take a ratio of these ratios, we obtain a useful and possibly surprising result: a small, whole-number ratio.

\[\mathrm{\dfrac{\dfrac{1.116\: g\: Cl}{1\: g\: Cu}}{\dfrac{0.558\: g\: Cl}{1\: g\: Cu}}=\dfrac{2}{1}}\]

This 2-to-1 ratio means that the brown compound has twice the amount of chlorine per amount of copper as the green compound.

This can be explained by atomic theory if the copper-to-chlorine ratio in the brown compound is 1 copper atom to 2 chlorine atoms, and the ratio in the green compound is 1 copper atom to 1 chlorine atom. The ratio of chlorine atoms (and thus the ratio of their masses) is therefore 2 to 1 (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)).

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\): Laws of Definite and Multiple Proportions

A sample of compound A (a clear, colorless gas) is analyzed and found to contain 4.27 g carbon and 5.69 g oxygen. A sample of compound B (also a clear, colorless gas) is analyzed and found to contain 5.19 g carbon and 13.84 g oxygen. Are these data an example of the law of definite proportions, the law of multiple proportions, or neither? What do these data tell you about substances A and B?

Solution

In compound A, the mass ratio of carbon to oxygen is:

\[\mathrm{\dfrac{1.33\: g\: O}{1\: g\: C}}\]

In compound B, the mass ratio of carbon to oxygen is:

\[\mathrm{\dfrac{2.67\: g\: O}{1\: g\: C}}\]

The ratio of these ratios is:

\[\mathrm{\dfrac{\dfrac{1.33\: g\: O}{1\: g\: C}}{\dfrac{2.67\: g\: O}{1\: g\: C}}=\dfrac{1}{2}}\]

This supports the law of multiple proportions. This means that A and B are different compounds, with A having one-half as much carbon per amount of oxygen (or twice as much oxygen per amount of carbon) as B. A possible pair of compounds that would fit this relationship would be A = CO2 and B = CO.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

A sample of compound X (a clear, colorless, combustible liquid with a noticeable odor) is analyzed and found to contain 14.13 g carbon and 2.96 g hydrogen. A sample of compound Y (a clear, colorless, combustible liquid with a noticeable odor that is slightly different from X’s odor) is analyzed and found to contain 19.91 g carbon and 3.34 g hydrogen. Are these data an example of the law of definite proportions, the law of multiple proportions, or neither? What do these data tell you about substances X and Y?

Answer:

In compound X, the mass ratio of carbon to hydrogen is \(\mathrm{\dfrac{14.13\: g\: C}{2.96\: g\: H}}\). In compound Y, the mass ratio of carbon to oxygen is \(\mathrm{\dfrac{19.91\: g\: C}{3.34\: g\: H}}\). The ratio of these ratios is \(\mathrm{\dfrac{\dfrac{14.13\: g\: C}{2.96\: g\: H}}{\dfrac{19.91\: g\: C}{3.34\: g\: H}}=\dfrac{4.77\: g\: C/g\: H}{5.96\: g\: C/g\: H}=0.800=\dfrac{4}{5}}\). This small, whole-number ratio supports the law of multiple proportions. This means that X and Y are different compounds.

Summary

The ancient Greeks proposed that matter consists of extremely small particles called atoms. Dalton postulated that each element has a characteristic type of atom that differs in properties from atoms of all other elements, and that atoms of different elements can combine in fixed, small, whole-number ratios to form compounds. Samples of a particular compound all have the same elemental proportions by mass. When two elements form different compounds, a given mass of one element will combine with masses of the other element in a small, whole-number ratio. During any chemical change, atoms are neither created nor destroyed.

Glossary

- Dalton’s atomic theory

- set of postulates that established the fundamental properties of atoms

- law of constant composition

- (also, law of definite proportions) all samples of a pure compound contain the same elements in the same proportions by mass

- law of definite proportions

- (also, law of constant composition) all samples of a pure compound contain the same elements in the same proportions by mass

- law of multiple proportions

- when two elements react to form more than one compound, a fixed mass of one element will react with masses of the other element in a ratio of small whole numbers

Contributors

Paul Flowers (University of North Carolina - Pembroke), Klaus Theopold (University of Delaware) and Richard Langley (Stephen F. Austin State University) with contributing authors. Textbook content produced by OpenStax College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 license. Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/85abf193-2bd...a7ac8df6@9.110).