14.6: Applications of Thermochemistry

- Page ID

- 46454

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Virtually all chemical processes involve the absorption or release of heat, and thus changes in the internal energy of the system. In this section, we survey some of the more common chemistry-related applications of enthalpy and the First Law. While the first two sections relate mainly to chemistry, the remaining ones impact the everyday lives of everyone.

Enthalpy diagrams and their uses

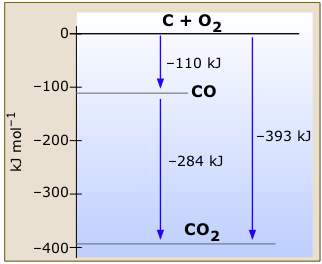

Comparison and interpretation of enthalpy changes is materially aided by a graphical construction in which the relative enthalpies of various substances are represented by horizontal lines on a vertical energy scale. The zero of the scale can be placed anywhere, since energies are always arbitrary; it is generally most useful to locate the elements at zero energy, which reflects the convention that their standard enthlapies of formation are zero.

This very simple enthalpy diagram for carbon and oxygen and its two stable oxides (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)) shows the changes in enthalpy associated with the various reactions this system can undergo. Notice how Hess’s law is implicit in this diagram; we can calculate the enthalpy change for the combustion of carbon monoxide to carbon dioxide, for example, by subtraction of the appropriate arrow lengths without writing out the thermochemical equations in a formal way.

The zero-enthalpy reference states refer to graphite, the most stable form of carbon, and gaseous oxygen. All temperatures are 298 K.

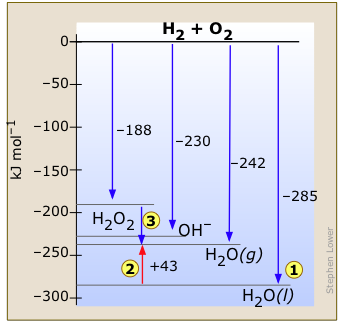

This enthalpy diagram for the hydrogen-oxygen system (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)) shows the known stable configurations of these two elements. Reaction of gaseous H2 and O2 to yield one mole of liquid water releases 285 kJ of heat  . If the H2O is formed in the gaseous state, the energy release will be smaller. Notice also that...

. If the H2O is formed in the gaseous state, the energy release will be smaller. Notice also that...

- The heat of vaporization of water

(an endothermic process) is clearly found from the diagram.

(an endothermic process) is clearly found from the diagram. - Hydrogen peroxide H2O2, which spontaneously decomposes into O2 and H2O, releases some heat

in this process. Ordinarily this reaction is so slow that the heat is not noticed. But the use of an appropriate catalyst can make the reaction so fast that it has been used to fuel a racing car.

in this process. Ordinarily this reaction is so slow that the heat is not noticed. But the use of an appropriate catalyst can make the reaction so fast that it has been used to fuel a racing car.

Why you cannot run your car on water

You may have heard the venerable urban legend, probably by now over 80 years old, that some obscure inventor discovered a process to do this, but the invention was secretly bought up by the oil companies in order to preserve their monopoly. The enthalpy diagram for the hydrogen-oxygen system shows why this cannot be true — there is simply no known compound of H and O that resides at a lower enthalpy level.

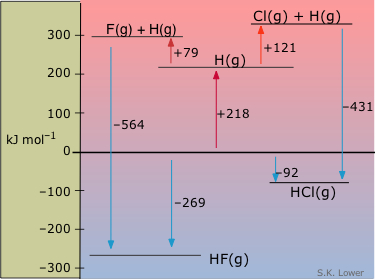

Enthalpy diagrams are especially useful for comparing groups of substances having some common feature. This one shows the molar enthalpies of species relating to two hydrogen halides, with respect to those of the elements. From this diagram we can see at a glance that the formation of HF from the elements is considerably more exothermic than the corresponding formation of HCl. The upper part of this diagram shows the gaseous atoms at positive enthalpies with respect to the elements. The endothermic processes in which the H2 and the dihalogen are dissociated into atoms can be imagined as taking place in two stages, also shown. From the enthalpy change associated with the dissociation of H2 (218 kJ mol–1), the dissociation enthalpies of F2 and Cl2 can be calculated and placed on the diagram.

Bond Enthalpies vs. Bond Energies

The enthalpy change associated with the reaction

\[\ce{HI(g) → H(g) + I(g)}\]

is the enthalpy of dissociation of the \(\ce{HI}\) molecule; it is also the bond energy of the hydrogen-iodine bond in this molecule. Under the usual standard conditions, it would be expressed either as the bond enthalpy H°(HI,298K) or internal energy U°(HI,298); in this case the two quantities differ from each other by ΔPV = RT. Since this reaction cannot be studied directly, the H–I bond enthalpy is calculated from the appropriate standard enthalpies of formation:

| ½ H2(g)→ H(g) | + 218 kJ |

| ½ I2(g)→ I(g) | +107 kJ |

| ½ H2(g) + 1/2 I2(g)→ HI(g) | –36 kJ |

| HI(g) → H(g) + I(g) | +299 kJ |

Bond energies and enthalpies are important properties of chemical bonds, and it is very important to be able to estimate their values from other thermochemical data. The total bond enthalpy of a more complex molecule such as ethane can be found from the following combination of reactions:

| C2H6(g)→ 2C(graphite) + 3 H2(g) | 84.7 kJ |

| 3 H2(g)→ 6 H(g) | 1308 kJ |

| 2 C(graphite) → 2 C(g) | 1430 kJ |

| C2H6(g)→ 2 C(g) + 6H(g) | 2823 kJ |

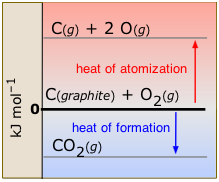

When a molecule in its ordinary state is broken up into gaseous atoms, the process is known as atomization (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). The standard enthalpy of atomization refers to the transformation of an element into gaseous atoms:

\[\ce{ C_{(graphite)} → C(g)} \;\;\;\; ΔH^o = 716.7\; kJ\]

Atomization is always an endothermic process. Heats of atomization are most commonly used for calculating bond energies. They are usually measured spectroscopically.

Pauling’s rule and Average Bond Energy

Pauling’s Rule

The total bond energy of a molecule can be thought of as the sum of the energies of the individual bonds.

Pauling’s Rule is only an approximation, because the energy of a given type of bond is not really a constant, but depends somewhat on the particular chemical environment of the two atoms. In other words, all we can really talk about is the average energy of a particular kind of bond, such as C–O, for example, the average being taken over a representative sample of compounds containing this type of bond, such as CO, CO2, COCl2, (CH3)2CO, CH3COOH, etc.

Despite the lack of strict additivity of bond energies, Pauling’s Rule is extremely useful because it allows one to estimate the heats of formation of compounds that have not been studied, or have not even been prepared. Thus in the foregoing example, if we know the enthalpies of the C–C and C–H bonds from other data, we could estimate the total bond enthalpy of ethane, and then work back to get some other quantity of interest, such as ethane’s enthalpy of formation. By assembling a large amount of experimental information of this kind, a consistent set of average bond energies can be obtained. The energies of double bonds are greater than those of single bonds, and those of triple bonds are higher still (Table \(\PageIndex{1}\)).

| H | C | N | O | F | Cl | Br | I | Si | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | 436 | 415 | 390 | 464 | 569 | 432 | 370 | 295 | 395 |

| C | 345 | 290 | 350 | 439 | 330 | 275 | 240 | 360 | |

| N | 160 | 200 | 270 | 200 | 270 | ||||

| O | 140 | 185 | 205 | 185 | 200 | 370 | |||

| F | 160 | 255 | 160 | 280 | 540 | ||||

| Cl | 243 | 220 | 210 | 359 | |||||

| Br | 190 | 180 | 290 | ||||||

| I | 150 | 210 | |||||||

| Si | 230 |

Energy Content of Fuels

A fuel is any substance capable of providing useful amounts of energy through a process that can be carried out in a controlled manner at economical cost. For most practical fuels, the process is combustion in air (in which the oxidizing agent O2 is available at zero cost.) The enthalpy of combustion is obviously an important criterion for a substance’s suitability as a fuel, but it is not the only one; a useful fuel must also be easily ignited, and in the case of a fuel intended for self-powered vehicles, its energy density in terms of both mass (kJ kg–1) and volume (kJ m–3) must be reasonably large. Thus substances such as methane and propane which are gases at 1 atm must be stored as pressurized liquids for transportation and portable applications.

|

|

|

|---|---|

| wood (dry) | 15 |

| coal (poor) | 15 |

| coal (premium) | 27 |

| ethanola | 30 |

| petroleum-derived products | 45 |

| methane, liquified natural gas | 54 |

| hydrogenb | 140 |

Notes on the above table

a Ethanol is being strongly promoted as a motor fuel by the U.S. agricultural industry. Note, however, that according to some estimates, it takes 46 MJ of energy to produce 1 kg of ethanol from corn. Some other analyses, which take into account optimal farming practices and the use of by-products arrive at different conclusions; see, for example, this summary with links to several reports.

b Owing to its low molar mass and high heat of combustion, hydrogen possesses an extraordinarily high energy density, and would be an ideal fuel if its critical temperature (33 K, the temperature above which it cannot exist as a liquid) were not so low. The potential benefits of using hydrogen as a fuel have motivated a great deal of research into other methods of getting a large amount of H2 into a small volume of space. Simply compressing the gas to a very high pressure is not practical because the weight of the heavy-walled steel vessel required to withstand the pressure would increase the effective weight of the fuel to an unacceptably large value. One scheme that has shown some promise exploits the ability of H2 to “dissolve” in certain transition metals. The hydrogen can be recovered from the resulting solid solution (actually a loosely-bound compound) by heating.

Energy content of foods

What, exactly, is meant by the statement that a particular food “contains 1200 calories” per serving? This simply refers to the standard enthalpy of combustion of the foodstuff, as measured in a bomb calorimeter. Note, however, that in nutritional usage, the calorie is really a kilocalorie (sometimes called “large calorie”), that is, 4184 J. Although this unit is still employed in the popular literature, the SI unit is now commonly used in the scientific and clinical literature, in which energy contents of foods are usually quoted in kJ per unit of weight.

Although the mechanisms of oxidation of a carbohydrate such as glucose to carbon dioxide and water in a bomb calorimeter and in the body are complex and entirely different, the net reaction involves the same initial and final states, and must be the same for any possible pathway:

\[C_6H_{12}O_6 + 6 O_2 → 6 CO_2 + 6 H_2O \;\;\;\; ΔH^o = – 20.8\; kJ \;mol^{–1}\]

Glucose is a sugar, a breakdown product of starch, and is the most important energy source at the cellular level; fats, proteins, and other sugars are readily converted to glucose. By writing balanced equations for the combustion of sugars, fats, and proteins, a comparison of their relative energy contents can be made. The stoichiometry of each reaction gives the amounts of oxygen taken up and released when a given amount of each kind of food is oxidized; these gas volumes are often taken as indirect measures of energy consumption and metabolic activity; a commonly-accepted value that seems to apply to a variety of food sources is 20.1 J (4.8 kcal) per liter of O2 consumed.

For some components of food, particularly proteins, oxidation may not always be complete in the body, so the energy that is actually available will be smaller than that given by the heat of combustion. Mammals, for example, are unable to break down cellulose (a polymer of sugar) at all; animals that derive a major part of their nutrition from grass and leaves must rely on the action of symbiotic bacteria which colonize their digestive tracts. The amount of energy available from a food can be found by measuring the heat of combustion of the waste products excreted by an organism that has been restricted to a controlled diet, and subtracting this from the heat of combustion of the food (Table \(\PageIndex{3}\)).

| type of food | food |

ΔH° (kJ g–1) |

percent availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | meat | 22.4 | 92 |

| egg | 23.4 | ||

| Fat | butter | 38.2 | |

| animal fat | 39.2 | 95 | |

| Carbohydrate | starch | 17.2 | |

| glucose (sugar) | 15.5 | 99 | |

| ethanol | 29.7 | 100 |

The amount of energy an animal requires depends on the age, sex, surface area of the body, and of course on the amount of physical activity. The rate at which energy is expended is expressed in watts: 1 W = 1 J sec–1. For humans, this value varies from about 200-800 W. This translates into daily food intakes having energy equivalents of about 10-15 MJ for most working adults. In order to just maintain weight in the absence of any physical activity, about 6 MJ per day is required.

| animal | kJ hr–1 | kJ kg–1hr–1 |

|---|---|---|

| mouse | 82 | 17 |

| cat | 34 | 6.8 |

| dog | 78 | 3.3 |

| sheep | 193 | 2.2 |

| human | 300 | 2.1 |

| horse | 1430 | 1.1 |

| elephant | 5380 | 0.7 |

The above table is instructive in that although larger animals consume more energy, the energy consumption per unit of body weight decreases with size. This reflects the fact the rate of heat loss to the environment depends largely on the surface area of an animal, which increases with mass at a greater rate than does an animal's volume ("size").

Thermodynamics and the weather

Hydrogen bonds at work

It is common knowledge that large bodies of water have a “moderating” effect on the local weather, reducing the extremes of temperature that occur in other areas. Water temperatures change much more slowly than do those of soil, rock, and vegetation, and this effect tends to affect nearby land masses. This is largely due to the high heat capacity of water in relation to that of land surfaces— and thus ultimately to the effects of hydrogen bonding. The lower efficiency of water as an absorber and radiator of infrared energy also plays a role.

The specific heat capacity of water is about four times greater than that of soil. This has a direct consequence to anyone who lives near the ocean and is familiar with the daily variations in the direction of the winds between the land and the water. Even large lakes can exert a moderating influence on the local weather due to water's relative insensitivity to temperature change.

During the daytime the land and sea receive approximately equal amounts of heat from the Sun, but the much smaller heat capacity of the land causes its temperature to rise more rapidly. This causes the air above the land to heat, reducing its density and causing it to rise. Cooler oceanic air is drawn in to fill the void, thus giving rise to the daytime sea breeze. In the evening, both land and ocean lose heat by radiation to the sky, but the temperature of the water drops less than that of the land, continuing to supply heat to the oceanic air and causing it to rise, thus reversing the direction of air flow and producing the evening land breeze.

Why it gets colder as you go higher: the adiabatic lapse rate

The air receives its heat by absorbing far-infrared radiation from the earth, which of course receives its heat from the sun. The amount of heat radiated to the air immediately above the surface varies with what's on it (forest, fields, water, buildings) and of course on the time and season. When a parcel of air above a particular location happens to be warmed more than the air immediately surrounding it, this air expands and becomes less dense. It therefore rises up through the surrounding air and undergoes further expansion as it encounters lower pressures at greater altitudes.

Whenever a gas expands against an opposing pressure, it does work on the surroundings. According to the First Law ΔU = q + w, if this work is not accompanied by a compensating flow of heat into the system, its internal energy will fall, and so, therefore, will its temperature. It turns out that heat flow and mixing are rather slow processes in the atmosphere in comparison to the convective motion we are describing, so the First Law can be written as ΔU = w (recall that w is negative when a gas expands.) Thus as air rises above the surface of the earth it undergoes adiabatic expansion and cools. The actual rate of temperature decrease with altitude depends on the composition of the air (the main variable being its moisture content) and on its heat capacity. For dry air, this results in an adiabatic lapse rate of 9.8 C° per km of altitude.

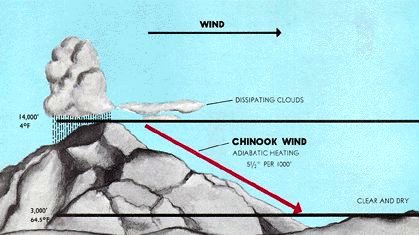

Santa Anas and Chinooks

Just the opposite happens when winds develop in high-altitude areas and head downhill. As the air descends, it undergoes compression from the pressure of the air above it. The surroundings are now doing work on the system, and because the process occurs too rapidly for the increased internal energy to be removed as heat, the compression is approximately adiabatic.

The resulting winds are warm (and therefore dry) and are often very irritating to mucous membranes. These are known generically as Föhn winds (which is the name given to those that originate in the Alps). In North America they are often called chinooks (or, in winter, "snow melters") when they originate along the Rocky Mountains. Among the most notorious are the Santa Ana winds of Southern California which pick up extra heat (and dust) as they pass over the Mohave Desert before plunging down into the Los Angeles basin (Figure 13.5.X). Their dryness and high velocities feed many of the disastrous wildfires that afflict the region.