6.10: Disubstituted Cyclohexanes

- Page ID

- 191295

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

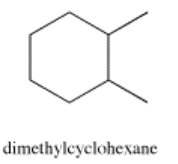

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Take a look at 1,2-dimethylcyclohexane. The two methyl (CH3) groups in this compound are on adjacent carbons.

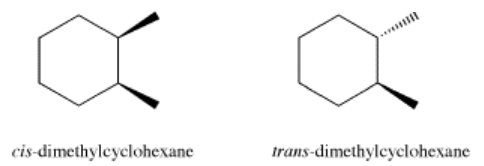

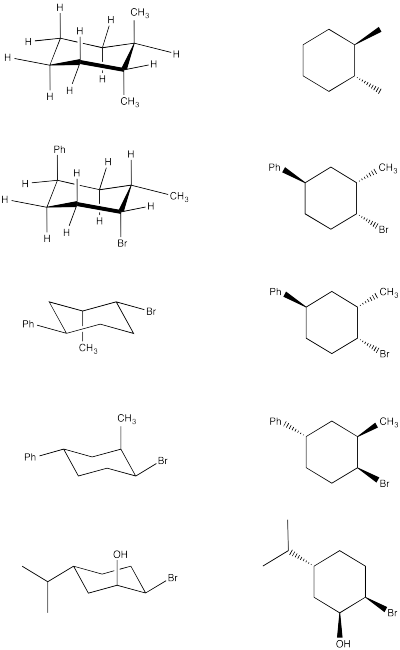

There are two ways these methyl groups could be attached to the ring: they can either be on the same face, as they are in the cis isomer; or they can be on opposite faces, as they are in the trans isomer.

The difference between these two compounds is pretty clear from a regular hexagon view of the molecule, with wedges and dashes denoting the spatial relationship between the methyl groups. Wedges show things coming towards us, on the near face of the ring, and dashes show things away from us, on the far face of the ring.

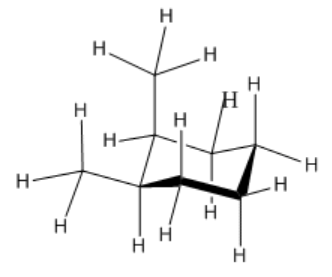

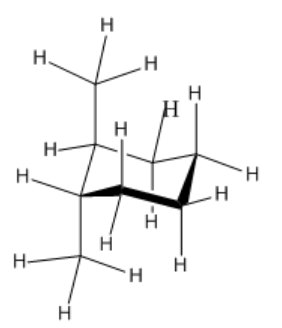

The diamond lattice drawing can be a little confusing, in this case.

- Remember that alternating corners of the ring point either up or down, and that each has an attached axial and equatorial position.

- The two methyl groups in cis-1,2-dimethylcyclohexane must occupy the axial position on one carbon and the equatorial position on the next.

That's because on a carbon that occupies a lower corner of the ring, the upper position that a methyl can occupy is equatorial, but for the next carbon, set in an upper corner of the chair, the upper position is an axial one. Viewed from the edge of the chair, two cis methyl groups would both be attached to either the upper face or the lower face of the chair, and so one would be axial and the other equatorial.

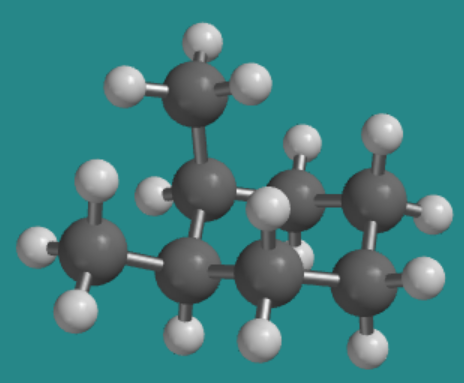

Go to Animation CA10.1. A three-dimensional model of cis-dimethylcyclohexane.

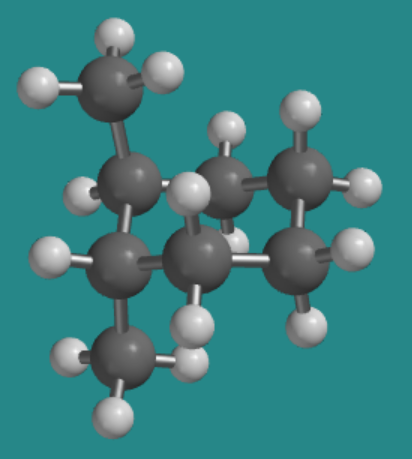

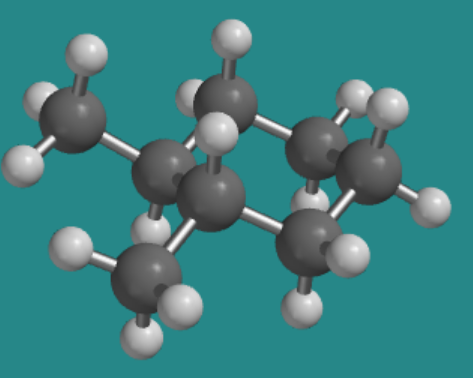

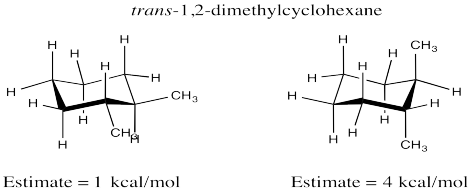

In trans-1,2-dimethylcyclohexane, the two methyl groups would occupy opposite faces of the ring. The easiest way to view this relationship is in a conformation in which the two methyl groups are in axial positions on adjacent carbons, one pointing up and the other down.

This view can also be seen in a model.

However, a ring flip converts the same molecule into a different conformer, in which both these groups are equatorial. The methyl groups no longer appear to be trans to each other, but they must be, because we haven't broken any bonds and this is still the same molecule we were looking at in the diaxial conformation.

In fact, given the two positions available at each ring carbon, one of the methyls is always in the uppermost position, whether it is in an axial or equatorial orientation, and the other methyl is always in the lowermost position.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

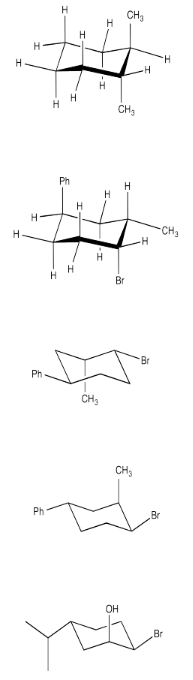

Convert the following chair structures to the wedge-dash projection.

- Answer

-

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

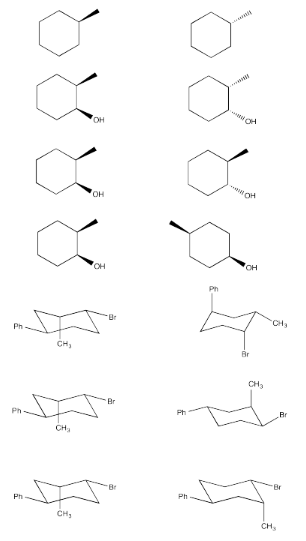

Determine the stereochemical relationship between these pairs of compounds.

- Answer

-

Exercise \(\PageIndex{3}\)

3. For the following the disubstituted cyclohexane rings:

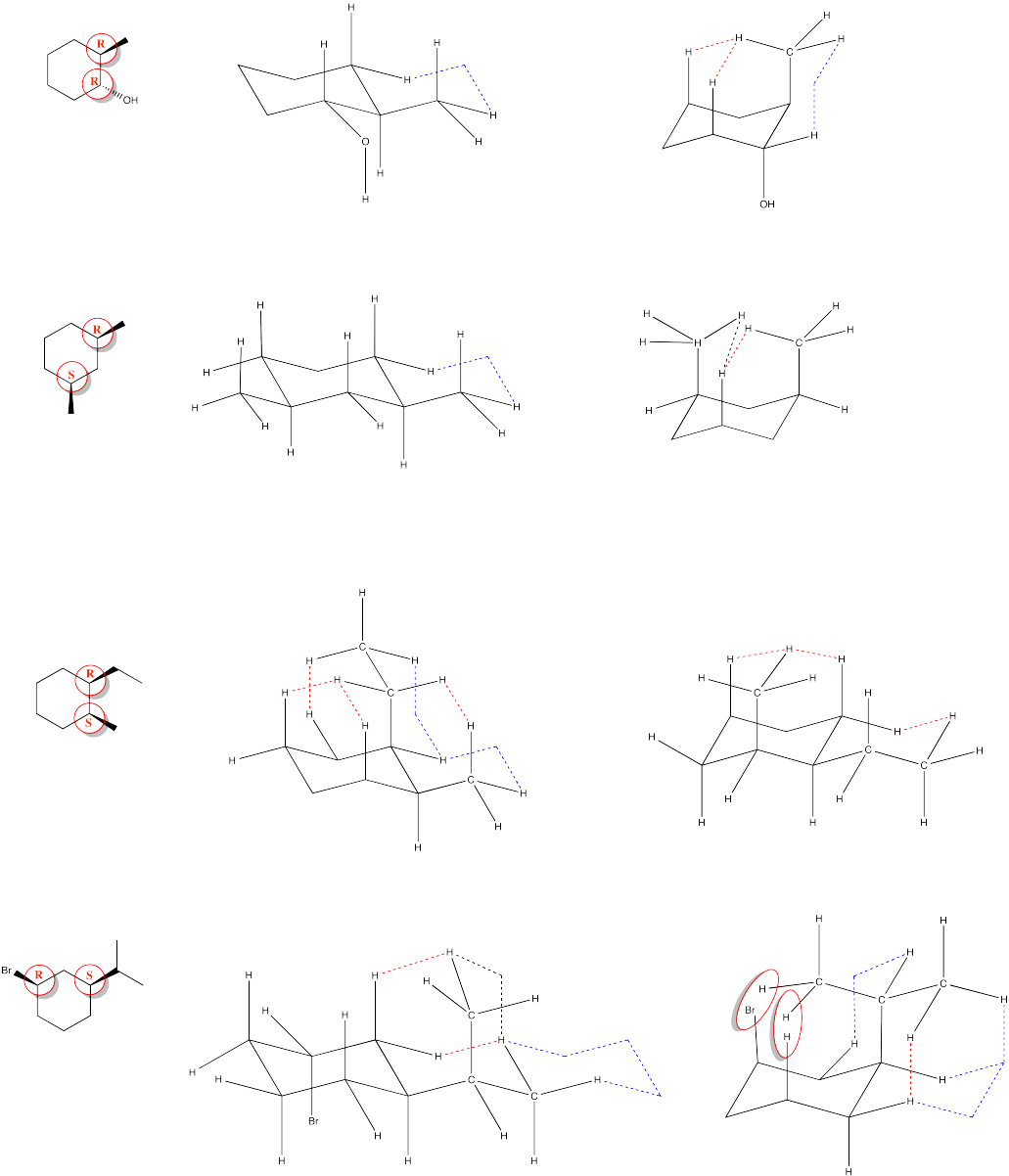

a. Circle all stereocenters and label them with the correct R/S designation.

b. Draw the two chair conformers on the diamond lattice. (Be careful not to draw the enantiomer).

- Answer

-

Exercise \(\PageIndex{4}\)

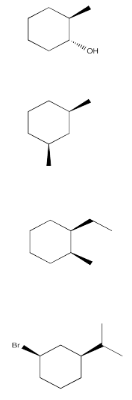

Perform an analysis of steric interactions in the chair conformation of trans-1,2-dimethylcyclohexane. After a ring flip, perform this analysis again. Compare the energy of the two conformers.

- Answer

-

It's tempting when working with models to take a group off and snap it back on somewhere else in order to think about different conformations, but that isn't a good idea. Taking a group off the model requires breaking a bond, and that isn't what happens when molecules convert between conformers. Instead, molecules simply twist into new shapes without breaking any bonds. If you snap pieces on and off your model while trying to evaluate conformations, you may end up with a different isomer altogether; for instance, it would be easy to accidentally convert cis-1,2-dimethylcyclohexane into trans-1.2-dimethylcyclohexane.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{5}\)

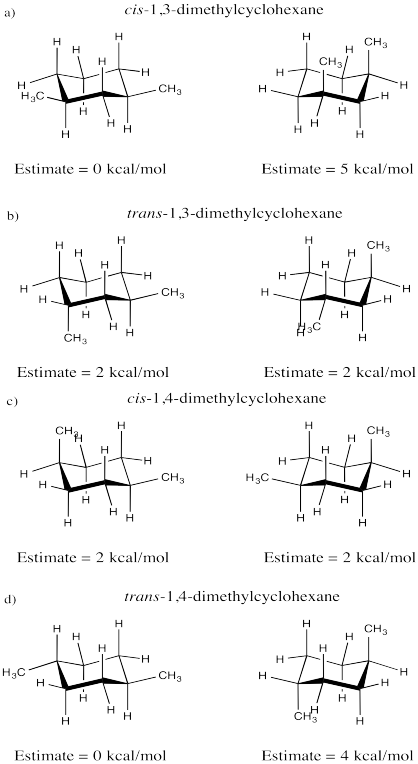

Perform an analysis of steric interactions in the two possible chair conformations of the following compounds.

a) cis-1,3-dimethylcyclohexane b) trans-1,3-dimethylcyclohexane

c) cis-1,4-dimethylcyclohexane d) trans-1,4-dimethylcyclohexane

- Answer

-

Still pictures of models obtained using Spartan 14 from Wavefunction, Inc., Irvine, California.