4.5: Nomenclature

- Page ID

- 279972

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

- Recognize ionic compound, molecular compounds, and acids.

- Give the names and formulas for ionic compounds

- Give the names and formulas for molecular compound s

- Give the name and formula for acidic compound

Introduction

Nomenclature, the naming of chemical compounds is of critical importance to the practice of chemistry, as a chemical can not only have many different names, but different chemicals can have the same name! So how can you do science if you do not know what you are talking about??? In this section we will look at nomenclature of simple chemical compounds. The rules we use depends on the type of compound we are attempting to name.

Overview of Nomenclature

The rules we use in nomenclature depend on the types of bonds the compound has and these are outlined in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) and the video lecture in video \(\PageIndex{1}\). That is, before we do anything we have to ask what kind of compound are we trying to name?

- The first question we ask is if the compound is ionic or covalent?

- If it is covalent, which is typically between 2 or more nonmetals, we need to ask, is it a simple molecule, or is it an acid.

- If it is a simple molecule we use Greek prefixes to identify the number of atoms of each type of element in the molecule.

- If it is an acid, we base it's name on the ionic compound it would form if hydrogen could be a cation. Note, hydrogen can not lose its only electron as then it would be a subatomic particle and the charge density would be too high, so it forms a covalent bond.

- If it is ionic, we use the principle of charge neutrality to name the compound.

- If it is covalent, which is typically between 2 or more nonmetals, we need to ask, is it a simple molecule, or is it an acid.

The following lesson will start with naming ionic compounds, then naming covalent compounds and then acids. After that, we will look at some special types of compounds, hydrated compounds (which are ionic compounds that contain water in their structure) and acid salts, which are salt's with acidic anions.

Ionic Compounds

When naming an ions the cation uses the metal's elemental name followed by the word ion or cation and the nonmetal anion uses the elemental name with an ide ending. So the metal sodium (Na) forms the sodium ion or sodium cation (Na+), while the nonmetal chloride (which exists as Cl2) is called chloride (Cl-), and you do not need to indicate that it is an ion (there is nothing wrong with the terms chloride anion or chloride ion, but they are providing redundant information).

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Give the symbol and name for the ion with 34 protons and 36 electrons. Is it a cation or an anion?

- Answer

-

\(Se^{2−}\), selenide. In it an anion since there are more electrons than protons.

Ionic compounds have a [+] cation and a [-] anion. We use the Principle of Charge Neutrality, that is, for an ionic compound to be stable its chemical formula MUST BE NEUTRAL. So you do not need to state the number of cations and anions, you only need to state what they are (and what the charge is for cations with variable charges). You then Figure the formula based on the lowest whole number ratio of cations to anions that produces a neutral formula.

We will start with binary ionic, which are between monatomic anions and cations. We note that there are two types of metals, those that have only 1 charge (Type 1), and those that can have more than one stable charge. Finally, polyatomic ions often form which are covalently bonded atoms where the total number of protons is not equal to the total number of electrons.

Binary Ionic

Binary ionic compounds are between a metal and nonmetal. This does not mean there are two atoms, but two types of atoms, so Al2S3 is a binary ionic compound. The rules are simple, name the cation first and the anion second, giving the anion the -ide suffix.

- Cation (metal) first

- Anion (nonmetal) second with -ide suffix

The problem is some metals have more than one stable charge state, and so for those metals (type 2 metals), we need to identify the charge in the name.

Two Types of Monatomic Cations

There are two types of monatomic cations, those of metals that form only one charge state, and those that can form multiple charged states, but there is only one type of monatomic anion as none of them form multiple charged states (review section 2.6.4.1) For simplicity, we are going to label the metal cations as Type 1 (invariant charge) and type 2 (variable charge)

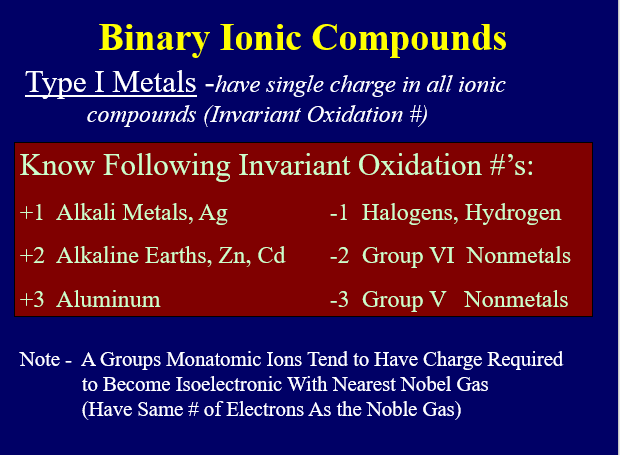

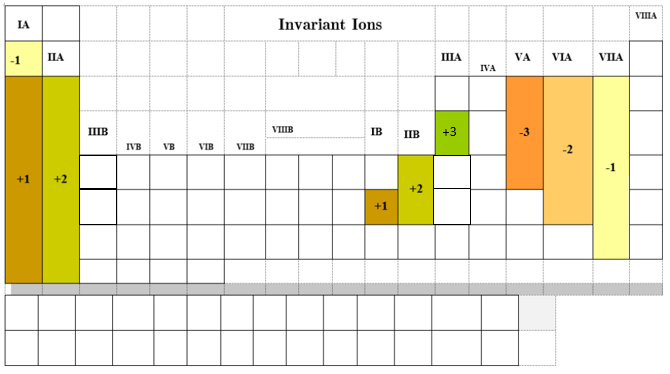

Type 1: Invariant Charge (Oxidation State)

Remember metals lose electrons to form cations and nonmetals gain electrons to form anions. Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) lists the ions (cations and anions) that have invariant charges. All the anions are of this type, gaining the number of electrons required to fill the valence shell and become isoelectronic with the nearest noble gas.

There is a pattern to the metals if you use the A/B block notation in that 1A & 1B tend to form [+1] , IIA & IIB tend to form [+2], while IIIA & IIIB tend to form [+3]. It is easy to see how the alkaline metals (1A) lose one electron as that gives them the same as a noble gas, but you need to get to Chapter 7 and understand the orbitals before you can understand why silver (1B) behaves the same. The alkaline earths (IIA) each lose 2 and gain the same electron configuration of a noble gas, while Zinc and Cadmium (IIB) also lose two electrons, but once again, we need to get to Chapter 7 to understand why. As for the [+3] forming ions, these are IIIA and IIIB. Now the B block are easier to see, as they simply loose three electrons, one from the IIIB, IIA and IA block of a period, and then they have the same number of electrons as a noble gas. As for the IIIA, we need to understand Chapter 7, but imagine that all of the orbitals of the transition metals are filled (B block) and the ones lost are from IA, IIA and IIIA.

|

|

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) The elements in the above table form only one stable charged state. Can you see the pattern for the cations in relation to the A/B block notation. Note, we often refer to the charge of a monatomic ion as its oxidation state, and the list of Type 1 Metals (invariant oxidation state) is more extensive in general chemistry (section 2.7.3.1)

Using the Principle of Charge Neutrality (section 4.1.2) and knowing the charge of the ions allows you to determine the formula. For type 1 metals is is very simple, you just name the metal, then the nonmetal and give the nonmetal an -ide ending. So table salt (NaCl) is sodium chloride.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

What is the formula for Barium Chloride?

- Answer

-

Barium is an alkaline earth and always forms a cation of charge of [+2], while chlorine is a halogen and always form the chloride ion of [-1]. For barium chloride to be neutral you would need two chlorides for every barium, and so the formula is BaCl2.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Name AlBr3

- Answer

-

Aluminum is always [+3] and bromide is always [-1] so it is aluminum bromide. The name does not have to tell how many cations and anions there are, as we know there are three [-1] bromides for every one [+3] aluminum ion, as otherwise it would not be neutral (review section 2.6.5.1)

Type II: Cations with Variable Charge (Oxidation State)

Most transition metals form multiple stable cations with different charges, and so you have to identify the charge state, which is done by writing the charge in Roman numerals and placing it in parenthesis after the name of the metal. So Fe+2 is iron(II) and Fe+3 is iron(III). Some of the metals form very common ions which have latin names that are in common use, and general chemistry students need to be familiar with those in the following table but prep chem do not.

Note the latin convention is to use:

- -ous ending for the lower oxidation state (charge)

- -ic ending for the higher oxidation state (charge)

Note mercury(1) is not a monoatomic cation, but is really a diatomic cation of two mercury atoms bound to each other, both having lost one electron. Polyatomic ions will be covered in the next section

Exercise \(\PageIndex{4}\)

What is the formula of mercury(I) chloride?

- Answer

-

Hg2Cl2, for every one Hg2-2 cation there must be two Cl- anions. So Hg2Cl2 it the lowest whole number ratio of cation to anion.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Give the names and formula of the two chloride salts that from with the common cations of iron.

Solution

NOTE: Review section 2.6.5 and Video 2.6.2 if you have problems calculating the formula in this example or the next exercise.

Example 2

| Ions: | Fe2+ and Cl- | Fe3+ and Cl- |

| Compound: | FeCl2 | FeCl3 |

| Nomenclature | Iron (II) Chloride or Ferrous Chloride | Iron (III) Chloride or Ferric Chloride |

Exercise \(\PageIndex{5}\)

Give the names and formula of the two nitride salts that from with the common cations of lead.

- Answer

-

Ions: Pb2+ and N-3 Pb4+ and N-3 Compound: Pb3N2 Fe3N4 Nomenclature Lead (II) nitride or Plumbous nitride Lead (IV) nitride or Plumbic Nitride

Polyatomic Ions

Polyatomic ions are covalent units (molecules) where the total number of protons \(\neq\) to the total number of electrons and they were introducedin section 4.4. They end in [-ide], [-ate] and [-ite]. Many of these are oxyanions with oxygen being bonded to a nonmetal and others are carboxylate ions . It should be noted that ionic compounds like ammonium acetate are composed entirely of nonmetals, but they form a crystal structure of cations and anion.

| Formula | Name | Formula | Name | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NH4+ | Ammonium | SO32– | Sulfite | |

| Hg22+ | Mercury (I) ion | SO42– | Sulfate | |

| ClO– | Hypochlorite | S2O32- | Thiosulfate | |

| ClO2– | Chlorite | CrO42– | Chromate | |

| ClO3– | Chlorate | Cr2O72– | Dichromate | |

| ClO4– | Perchlorate | CN– | Cyanide | |

| NO2– | Nitrite | SCN– | Thiocyanate | |

| NO3– | Nitrate | OH– | Hydroxide | |

| CO32– | Carbonate | O22– | Peroxide | |

| HCO3– | Bicarbonate | MnO4– | Permanganate | |

| PO43– | Phosphate | C2O42- | Oxalate | |

| PO33– | Phosphite | C8H4O42- | Phthalate | |

| C2H3O2- | Acetate |

Naming Oxyanions: Oxyanions are polyatomic ions where oxygen is attached to a nonmetal, nonmetals of the same periodic group from homologous oxyanions. Lets look at the 4 oxyanions of bromine

- perbromate (BrO4-)

- bromate (BrO3-)

- bromite (BrO2-)

- hypobromite (BrO-)

These all end with -ate or -ite, and the real reasoning deals with the oxidation state of the nonmetal, sort of its hypothetical charge within the covalently bonded polyatomic ion. We will cover that in a later Chapter, but right now we note that the "-ate" ions have more oxygens and the "-ites" have less, with "per____ate" having the most, and "hypo___ite" having the least.

Overview of video:

- Oxyacids have same charge as central atom's monatomic ion (except for the first period)

- nitride, phosphide,arsenide = [-3] so oxyanions of phosphorous & Arsenic = [-3], but of nitrogen = [-1]*

- oxide, sulfide, selenide, telluride = [-2] so oxyanions of sulfur, selenium & tellurium = [-2], oxygen does not form same kind of anions

- fluoride, chloride, bromide, iodide = [-1], so oxyanions of chlorine, bromine, & iodine = [-1], fluorine's also = [-1] but I think only hypofluorite really exits, although I have seen the others on exams. For example, a search of PubChem for perfluorate gives no hits.

- ate implies more oxygens

- hyper___ate implies even more oxygen

- ite implies less oxygens

- hypo___ite implies even fewer oxygen.

*Note, nitrite and nitrate are the only oxyanions with a charge different than the monatomic anoin

Naming Carboxylate ions: Carboxylate ions are very common in organic chemistry. The following YouTube uses the structure of the carboxylate functional group as a tool to assist in remembering the formulas.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{6}\)

Name the following compounds:

A) NiCO3

B) Sr(NO2)2

C) NH4NO3

- Answer

-

A) Nickel(II) carbonate. Nickel is a Type II cation, so you need a Roman Numeral. To Figure out that charge "x", we need take a look at what we know. There is one carbonate ion at a charge of -2. There is one Nickel ion at unknown charge "x". 1(x) + 1(-2) = 0. To be charge neutral, x=+2.

B) Strontium nitrite. Strontium is a type I cation and there is no need for a Roman Numeral. NO2- is the nitrite ion.

C) Ammonium nitrate. both are polyatomic ions, so you simply state the name of cation followed by the name of the anion.

Covalent Compounds

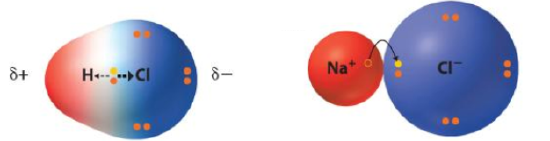

Molecules are compounds held together by covalent bonds. In figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) we see that there are two types of covalent compounds, what we are calling "classical molecules", and acids. Hydrogen like all the alkali metals only has one electron in its outer shell, but unlike the other elements of the first period (group 1A) you can not remove the electron and make an ion because all that is left would be a proton, which is a sub-atomic particle. This creates a class of molecules called acids, where hydrogen effectively takes the place of the cation, and the resulting bond is a polar covalent bond where the electron is unequally shared. Classical molecules occur when nonmetals form covalent bonds with each other and this can get very complicated. Organic chemistry is based on the study of carbon based molecules and uses IUPAC nomenclature which is beyond the level of this course (the IUPAC Nomenclature book for organic compounds is 1568 pages long!). We will first cover simple molecules and then acids.

Simple Molecules

In this class we will look at the nomenclature of very simple small molecules that form when two or more nonmetals share covalent electrons and form a classical molecule. In a molecule the formula represents the chemical entity, where as in an ionic compound, it is the lowest whole number ratio of cation to anion. So molecules like P2O5 and P4O10 have the same ratio of phosphorous to oxygen, but they are different molecules, and so we need a nomenclature system that tells how many atoms of each element are in the compound.

The rules are simple, before each atom we place a Greek prefix indicating the number of those atoms in the formula. If there is only on atom, we often omit the prefix "mono". In this class we will name molecules with no more than 10 atoms of each type and you need to memorize the 10 prefixes in table \(\PageIndex{2}\).

| # of Atoms | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Prefixes | Mono- | Di- | Tri- | Tetra- | Penta- | Hexa- | Hepta- | Octa- | Nona- | Deca- |

There are some rules we need to follow,which are:

- If there are two atoms, place the more "metallic" first (furthest to the left on the periodic table)

- is there is a central atom, place it first, and the atoms attached after.

- If there are more than two atoms, place in order of bonds

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Give the names for: CO, BCl3

Give the formula for: carbon dioxide, dinitrogen pentoxide

Solution

CO = carbon monoxide BCl3 = borontrichloride

carbon dioxide= CO2 dinitrogen pentoxide = N2O5

Exercise \(\PageIndex{7}\)

Name each molecule.

- SF4

- P2S5

- N2O4

- P4S10

- Answer a

-

sulfur tetrafluoride

- Answer b

-

diphosphorus pentasulfide

- Answer c

-

dinitrogen tetraoxide

- Answer d

-

tetraphosphorus decasulfide

Exercise \(\PageIndex{8}\)

Give the formula for each molecule.

- disulfur difluoride

- iodine pentabromide

- nitrogen trifluoride

- diphosphorous pentaoxide

- Answer a

-

\(\ce{S2F2 }\)

- Answer b

-

\(\ce{IBr5}\)

- Answer c

-

\(\ce{NF3}\)

- Answer d

-

\(\ce{P2O5}\)

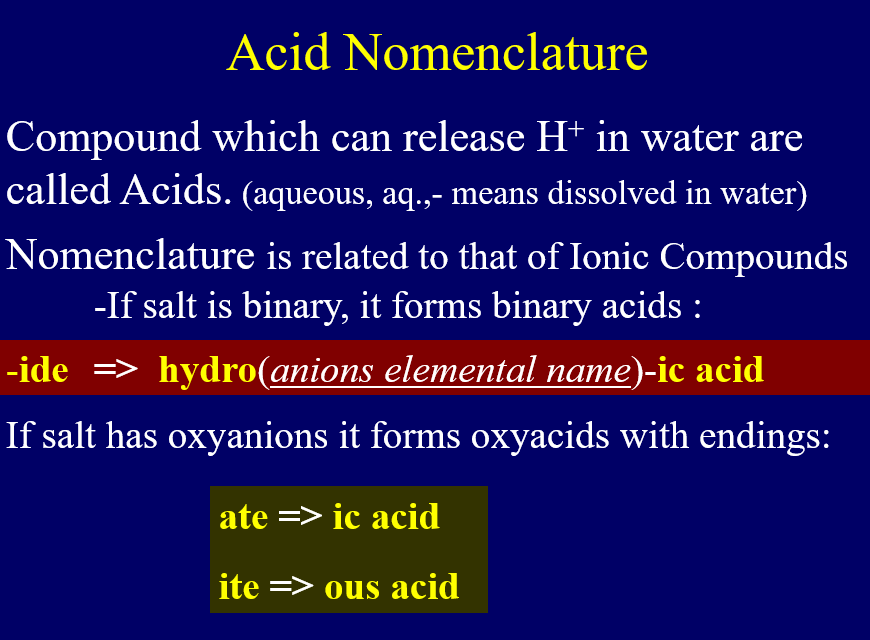

Acids

In a binary ionic compound an alkali metal typically loses an electron to a nonmetal forming an [+1] cation while the nonmetal forms an anion. The resulting cation has core (inner shell) electrons that give it volume and surround the nucleus with electrons resulting in a stable ion, even if the net charge is positive. Hydrogen is also in group IA but has no inner shell electrons, and so it can't form a cation, as that would be a subatomic particle and the charge density would be so great that it would attract the electron back. So what happens is an unequal sharing of the electron and hydrogen forms an acidic bond with anions that is of the same formula as the other group 1A alkali metals would form. So acid nomenclature is based on that of an ionic compound.

When an acid dissolves in water the proton is transferred to a water forming hydronium ion H3O+ and thus dissociates forming the same anion as the analogous salt.

\[HCl(aq) \rightarrow H^+ + Cl^-\\ NaCl(aq) \rightarrow Na^+ + Cl^-\]

where H+ really exists as H3O+ in the water (the proton is transferred to water).

So we could say sodium chloride is a salt with a common ion to HCl. Because of this, we base the name of the acid on it's salt. Since there are three endings to salts (-ide, -ite, -ate), there are three correlating names for acids.

- -ide becomes hydro [anion stem]ic acid

- -ite becomes [anion stem]ous acid

- -ate becomes [anion stem]ic acid

|

|

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\): The rules for acid nomenclature as based on the nomenclature of ionic compounds

Compare the questions and answers of exercise \(\PageIndex{9}\) and \(\PageIndex{10}\) to so this relationship for the salts and acids of chlorine

Exercise \(\PageIndex{9}\)

Name the five sodium salts of chlorine.

- NaCl

- NaClO

- NaClO2

- NaClO3

- NaClO4

- Answer a

-

Sodium chloride

- Answer b

-

Sodium hypochlorite

- Answer c

-

Sodium chlorite

- Answer d

-

Sodium chlorate

- Answer e

-

Sodium perchlorate

Exercise \(\PageIndex{10}\)

Name the five acids of chlorine.

- HCl

- HClO

- HClO2

- HClO3

- HClO4

- Answer a

-

Hydrochloric acid

- Answer b

-

Hypochlorous acid

- Answer c

-

Chlorous acid

- Answer d

-

Chloric acid

- Answer e

-

Perchloric acid

Test Yourself

Homework: Section 4.5

Graded Assignment: Section 4.5

Query \(\PageIndex{1}\)

The following set has 24 questions and randomly loads 10

Query \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Query \(\PageIndex{3}\)

The following set has 31 questions and randomly generates 10

Query \(\PageIndex{4}\)

d

Contributors and Attributions

Robert E. Belford (University of Arkansas Little Rock; Department of Chemistry). The breadth, depth and veracity of this work is the responsibility of Robert E. Belford, rebelford@ualr.edu. You should contact him if you have any concerns. This material has both original contributions, and content built upon prior contributions of the LibreTexts Community and other resources, including but not limited to:

- November Palmer, Ronia Kattoum & Emily Choate (UALR)

- Elena Lisitsyna (H5P interactive modules)