14.1: Overview

- Page ID

- 225860

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Electrophilic aromatic substitution (EAS) reactions – the general picture

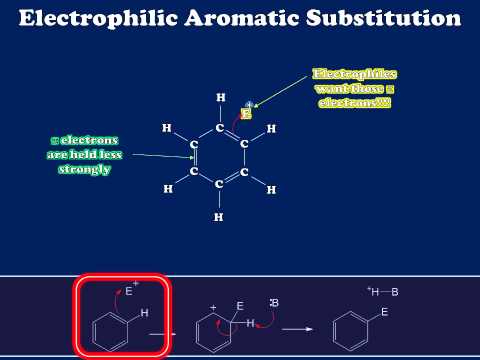

Although the delocalized pi electrons in aromatic rings are much less reactive than those in isolated or conjugated alkenes, they can undergo electrophilic reactions given a powerful enough electrophile. Electrophilic addition to aromatic double bonds, however, is not generally observed – this would be energetically unfavorable because it would result in a loss of aromaticity in the product.

Rather, aromatic double bonds undergo electrophilic substitution reactions, (abbreviated SEAr), which are mechanistically very similar to the substitutive addition-elimination reactions of alkenes. The product of an SEAr reaction, like the starting compound, is aromatic.

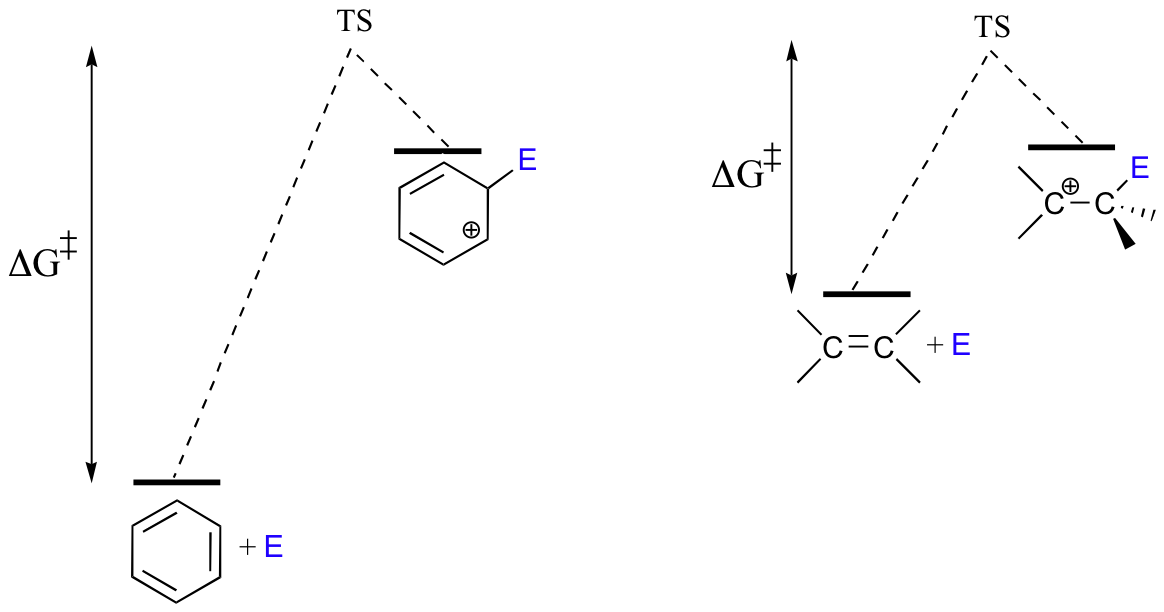

Because the starting point in an SEAr reaction is inherently low in energy (due to aromaticity), the activation energy for the first electrophilic step – in which aromaticity is temporarily lost in the carbocation intermediate- is correspondingly high. This is why aromatic pi bonds are significantly less reactive in electrophilic steps compared to the π bonds of nonaromatic alkenes.

As a consequence, SEAr reactions tend to share two basic characteristics. First, the electrophilic partner needs to be highly reactive – this serves to increase the energy of the starting point and decrease the activation energy. A second common characteristic that we will see in many SEAr reactions is that the reaction is often affected by the presence of substituents on the aromatic ring. These substituents will affect the rate of reaction and the position of electrophilic attack.

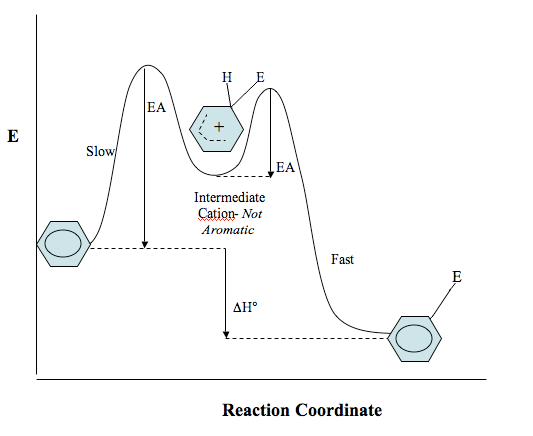

Reaction coordinate diagram of an EAS reaction

Below is a reaction coordinate diagram showing the reaction of benzene with an electrophile. The intermediate formed is sometimes referred to as a Wheland intermediate. Remember that this intermediate is not aromatic, even though it is somewhat stabilized by resonance, so it is much less stable than the aromatic starting material and product. Anything which stabilizes the Wheland intermediate also lowers the energy of the transition state. This reduces the activation energy, thereby speeding up the reaction (recall Hammond’s postulate, section 5.5.) .

References

- Klein, David R. Organic Chemistry II as a Second Language. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2006

- Parsons, A.F. Keynotes in Organic Chemistry. Oxford; Malden, MA: Blackwell Science, 2003

- Taylor, R. Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution. Chichester, West Sussex, England; New York: J. Wiley, 1990

Exercises

- Label the hybridization on all the carbons in a) reacting benzene ring, b) intermediate (including resonance forms), and c) product (monosubstituted benzene ring)

- Is the energy of activation higher in the first step or second step of the mechanism? Explain your reasoning.

- If you wanted to halogenate benzene, what sort of reagent and catalyst (if needed) would you use?

- Which hydrogren is used in order to regain aromaticity after the electrophile has added to the ring?

- Critical Thinking Question: Mentioned above was the fact that electrophilic aromatic substitution can and does happen when there are substituents already present on the ring. Already present substituents will determine where something adds onto the ring in relation to itself (ortho, meta, or para position). What sort of factors do you think influence where addition will occur?

Answers

[reveal-answer q=”770270″]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a=”770270″]

- a) All are sp2 b) Five carbons are sp2, the carbon with the attached E is sp3 hybridized c) All are sp2

- The activation energy is higher for the first step- aromatic compounds are lower in energy (“happier”) than their non-aromatic forms. Therefore it takes more energy to change a compound from being aromatic to non-aromatic, than it does in the reverse direction.

- $$X_2 (X=Cl, Br) + FeX_3$$

- The hydrogen used is the one attached to the same carbon that E added to

- Critical Thinking: If you came up with a) Inductive Effects (correlates to electronegativity) b) Resonance effects c) Electrostatics d) Steric Hindrance then good job! All of these influence where a substituent will add to the ring. Go to Activating and Deactivating Benzene Rings to find out more about how position is determined.[/hidden-answer]

Contributors

- Stevie Maxwell (UCD)

Biological example: An enzymatic electrophilic aromatic substitution reaction

The electrophile in an enzymatic SEAr reaction is usually a carbocation. One example of an SEAr reaction can be found in the biosynthesis of vitamin K. In this reaction, an isoprenoid chain is transferred to a phenol ring as part of the and related biomolecules. In this example, carbocation intermediate B is stabilized by resonance with the electron-donating phenol oxygen.

Contributors

- Organic Chemistry With a Biological Emphasis by Tim Soderberg (University of Minnesota, Morris)

- 15.5: Electrophilic aromatic substitution reactions. Authored by: Tim Soderberg. Provided by: University of Minnesota, Morris. Located at: https://chem.libretexts.org/Textbook_Maps/Organic_Chemistry/Book%3A_Organic_Chemistry_with_a_Biological_Emphasis_(Soderberg)/15%3A_Electrophilic_reactions/15.05%3A_Electrophilic_aromatic_substitution_reactions. Project: Organic Chemistry With a Biological Emphasis. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike