Chapter 14.6: Controlling the Products of Reactions

- Page ID

- 42123

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\) |

Prince George's Community College |

|

| Unit I: Atoms Unit II: Molecules Unit III: States of Matter Unit IV: Reactions Unit V: Kinetics & Equilibrium Unit VI: Thermo & Electrochemistry Unit VII: Nuclear Chemistry |

||

Learning Objectives

- To understand different ways to control the products of a reaction.

Whether in the synthetic laboratory or in industrial settings, one of the primary goals of modern chemistry is to control the identity and quantity of the products of chemical reactions. For example, a process aimed at synthesizing ammonia is designed to maximize the amount of ammonia produced using a given amount of energy. Alternatively, other processes may be designed to minimize the creation of undesired products, such as pollutants emitted from an internal combustion engine. To achieve these goals, chemists must consider the competing effects of the reaction conditions that they can control.

One way to obtain a high yield of a desired compound is to make the reaction rate of the desired reaction much faster than the reaction rates of any other possible reactions that might occur in the system. Altering reaction conditions to control reaction rates, thereby obtaining a single product or set of products, is called kinetic controlThe altering of reaction conditions to control reaction rates, thereby obtaining a single desired product or set of products. A second approach, called thermodynamic control. The altering of reaction conditions so that a single desired product or set of products is present in significant quantities at equilibrium., consists of adjusting conditions so that at equilibrium only the desired products are present in significant quantities.

The Haber-Bosch Process for Synthesis of Ammonia

An example of thermodynamic control is the Haber-Bosch process. Karl Bosch (1874–1940) was a German chemical engineer who was responsible for designing the process that took advantage of Fritz Haber’s discoveries regarding the N2 + H2/NH3 equilibrium to make ammonia synthesis via this route cost-effective. He received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1931 for his work. The industrial process is called either the Haber process or the Haber-Bosch process. used to synthesize ammonia via the following reaction:

\[N_{2(g)}+3H_{2(g)} \rightleftharpoons 2NH_{3(g)} \tag{14.6.1a}\]

with

\[ΔH_{rxn}=−91.8\; kJ/mol \tag{14.6.1b}\]

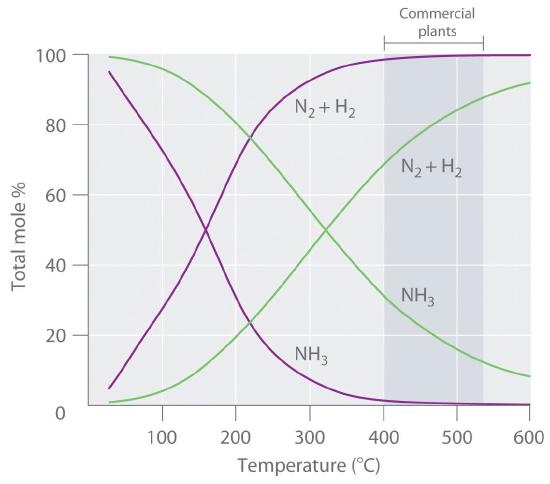

Because the reaction converts 4 mol of gaseous reactants to only 2 mol of gaseous product, Le Châtelier’s principle predicts that the formation of NH3 will be favored when the pressure is increased. The reaction is exothermic, however (ΔHrxn = −91.8 kJ/mol), so the equilibrium constant decreases with increasing temperature, which causes an equilibrium mixture to contain only relatively small amounts of ammonia at high temperatures (Figure 14.6.1). Taken together, these considerations suggest that the maximum yield of NH3 will be obtained if the reaction is carried out at as low a temperature and as high a pressure as possible. Unfortunately, at temperatures less than approximately 300°C, where the equilibrium yield of ammonia would be relatively high, the reaction is too slow to be of any commercial use. The industrial process therefore uses a mixed oxide (Fe2O3/K2O) catalyst that enables the reaction to proceed at a significant rate at temperatures of 400°C–530°C, where the formation of ammonia is less unfavorable than at higher temperatures.

Figure 14.6.1 Effect of Temperature and Pressure on the Equilibrium Composition of Two Systems that Originally Contained a 3:1 Mixture of Hydrogen and Nitrogen At all temperatures, the total pressure in the systems was initially either 4 atm (purple curves) or 200 atm (green curves). Note the dramatic decrease in the proportion of NH3 at equilibrium at higher temperatures in both cases, as well as the large increase in the proportion of NH3 at equilibrium at any temperature for the system at higher pressure (green) versus lower pressure (purple). Commercial plants that use the Haber-Bosch process to synthesize ammonia on an industrial scale operate at temperatures of 400°C–530°C (indicated by the darker gray band) and total pressures of 130–330 atm.

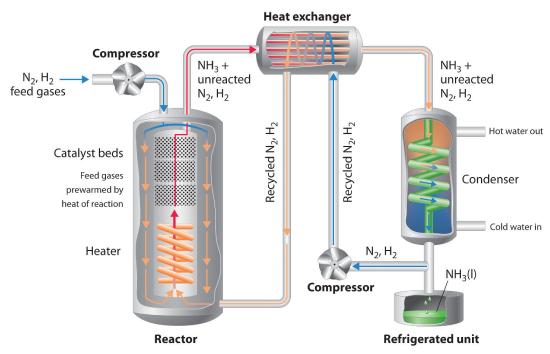

Because of the low value of the equilibrium constant at high temperatures (e.g., K = 0.039 at 800 K), there is no way to produce an equilibrium mixture that contains large proportions of ammonia at high temperatures. We can, however, control the temperature and the pressure while using a catalyst to convert a fraction of the N2 and H2 in the reaction mixture to NH3, as is done in the Haber-Bosch process. This process also makes use of the fact that the product—ammonia—is less volatile than the reactants. Because NH3 is a liquid at room temperature at pressures greater than 10 atm, cooling the reaction mixture causes NH3 to condense from the vapor as liquid ammonia, which is easily separated from unreacted N2 and H2. The unreacted gases are recycled until complete conversion of hydrogen and nitrogen to ammonia is eventually achieved. Figure 14.6.2 is a simplified layout of a Haber-Bosch process plant.

Figure 14.6.2 A Schematic Diagram of an Industrial Plant for the Production of Ammonia via the Haber-Bosch Process A 3:1 mixture of gaseous H2 and N2 is compressed to 130–330 atm, heated to 400°C–530°C, and passed over an Fe2O3/K2O catalyst, which results in partial conversion to gaseous NH3. The resulting mixture of gaseous NH3, H2, and N2 is passed through a heat exchanger, which uses the hot gases to prewarm recycled N2 and H2, and a condenser to cool the NH3, giving a liquid that is readily separated from unreacted N2 and H2. (Although the normal boiling point of NH3 is −33°C, the boiling point increases rapidly with increasing pressure, to 20°C at 8.5 atm and 126°C at 100 atm.) The unreacted N2 and H2 are recycled to form more

Below are videos showing how the process is carried out. The first step is generation of hydrogen gas by reaction of methane and steam on a nickel catalyst.

\[ CH_{4}(g) + H_{2} O(g)<=> CO(g) + 3H_{2}(g) \tag{14.6.2a}\]

followed by

\[ CO(g) + H_{2} O(g)<=> CO_{2}(g) + H_{2}(g) \tag{14.6.2b}\]

Any remaining methane is converted to carbon dioxide by reaction with air leaving a mix of pure nitrogen, hydrogen and carbon dioxide, The carbon dioxide then has to be scrubbed out from the gas mixture leaving a 3:1 mixture of hydrogen gas and nitrogen which is fed into the ammonia converter. Formation of ammonia requires a catalyst to break the nitrogen bond. On the iron catalyst the N2 and H2 atomize and react to form an equilibrium mixture of NH3, N2 and H2, which is about 15% ammonia. The gas in the reactor flows continually through an external cooler which condenses the ammonia and returns the remaining N2 and H2 to the reactor which further react to form more ammonia.

The first video below, from BASF, shows a schematic version of the Haber-Bosch process.

Having viewed the video we can write the seven reactions that are involved in the process where ad indicates that the molecule or atom is adsorbed on the catalyst

\( H_{2} \rightleftharpoons 2H^{_{\mathit{ad}}} \tag{14.6.3a} \)

\( N_{2} \rightleftharpoons N_{2 \mathit{ad}} \tag{14.6.3b} \)

\( N_{2 \mathit{ad}} \rightleftharpoons 2N_{\mathit{ad}} \tag{14.6.3c} \)

\( H_{\mathit{ad}} + N_{\mathit{ad}} \rightleftharpoons NH_{\mathit{ad}} \tag{14.6.3d} \)

\( NH_{\mathit{ad}} + H_{\mathit{ad}} \rightleftharpoons NH_{2\mathit{ad}} \tag{14.6.3e} \)

\( NH_{2\mathit{ad}} + H_{\mathit{ad}} \rightleftharpoons NH_{3\mathit{ad}} \tag{14.6.3f} \)

\( NH_{3\mathit{ad}} \rightleftharpoons NH_{3} \tag{14.6.3g} \)

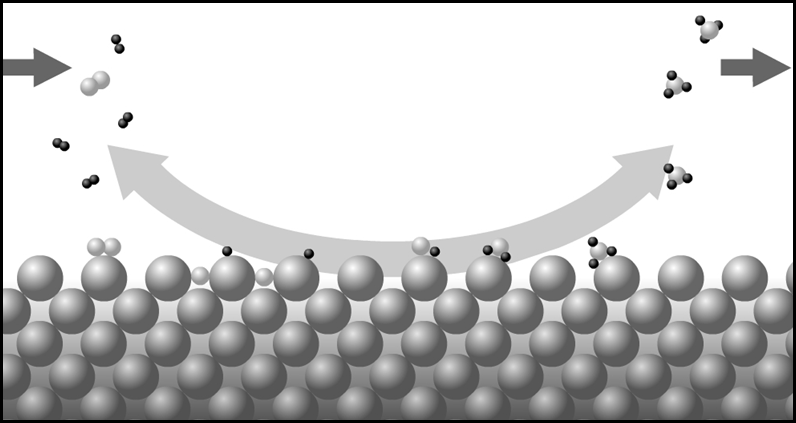

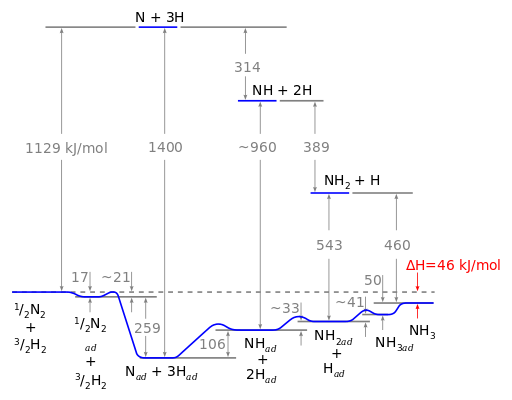

Reaction 14.6.3 is much the slowest, and therefore the rate determining step. Figure 14.6.3 summarizes the reaction scheme

Figure 14.6.3: A representation of the reactions Eqs. 14.6.3a - 14.6.3g with H2 and N2 coming in from the left and being adsorbed on the catalyst. The H2 and N2 then atomize on the surface of the catalyst, followed by a set of sequential reactions forming NH, NH2 and finally NH3 which desorbs from the catalyst as shown on the right

Gerhard Ertl worked out the energetics of the reaction shown in Figure 14.6.4 below shows the amount of energy per mole needed on the catalyst and that which would be needed in the gas phase. Ertl's Nobel Prize speech about his work on the catalytic reactions forming ammonia and other catalytic reactions can be viewed on line

Figure 14.6.4: Ertl's group was able to measure the energy needed for each step of the Bosch-Haber process as opposed to the energy that would be needed in the gas phase

The second video from the Royal Society of Chemistry gives you a tour through a ammonia plant.

The Sohio Acrylonitrile Process

The Sohio acrylonitrile process, in which propene and ammonia react with oxygen to form acrylonitrile, is an example of a kinetically controlled reaction:

\[\ce{CH_2=CHCH_{3(g)} + NH_{3(g)} + 3/2 O_{2(g)} <=> CH_2=CHC≡N_{(g)} + 3H_2O_{(g)}} \tag{14.6.4}\]

Like most oxidation reactions of organic compounds, this reaction is highly exothermic (ΔH° = −519 kJ/mol) and has a very large equilibrium constant (K = 1.2 × 1094). Nonetheless, the reaction shown in Equation 14.6.2 is not the reaction a chemist would expect to occur when propene or ammonia is heated in the presence of oxygen. Competing combustion reactions that produce CO2 and N2 from the reactants, such as those shown in Equation 14.6.5 and Equation 14.6.6, are even more exothermic and have even larger equilibrium constants, thereby reducing the yield of the desired product, acrylonitrile:

\[ \ce{CH_2=CHCH_{3(g)} + 9/2 O_{2(g)} <=> 3CO_{2(g)} + 3H_2O_{(g)}} \tag{14.6.5a}\]

with

\[ΔH^°=−1926.1 \;kJ/mol \tag{14.6.5b}\]

and

\[K=4.5 \times 10^{338} \tag{14.6.5c}\]

\[\ce{2NH_{3(g)} + 3 O_{2(g)} <=> N_{2(g)} + 6H_2O_(g)} \tag{14.6.6a}\]

with

\[ΔH°=−1359.2 \;kJ/mol, \tag{14.6.6b}\]

and

\[K=4.4 \times 10^{234} \tag{14.6.6c}\]

In fact, the formation of acrylonitrile in Equation 14.6.4. is accompanied by the release of approximately 760 kJ/mol of heat due to partial combustion of propene during the reaction.

The Sohio process uses a catalyst that selectively accelerates the rate of formation of acrylonitrile without significantly affecting the reaction rates of competing combustion reactions. Consequently, acrylonitrile is formed more rapidly than CO2 and N2 under the optimized reaction conditions (approximately 1.5 atm and 450°C). The reaction mixture is rapidly cooled to prevent further oxidation or combustion of acrylonitrile, which is then washed out of the vapor with a liquid water spray. Thus controlling the kinetics of the reaction causes the desired product to be formed under conditions where equilibrium is not established. In industry, this reaction is carried out on an enormous scale. Acrylonitrile is the building block of the polymer called polyacrylonitrile, found in all the products referred to collectively as acrylics, whose wide range of uses includes the synthesis of fibers woven into clothing and carpets.

Note the Pattern

Controlling the amount of product formed requires that both thermodynamic and kinetic factors be considered.

Example 14.6.1

Recall that methanation is the reaction of hydrogen with carbon monoxide to form methane and water:

\[CO_{(g)} +3H_{2(g)} \rightleftharpoons CH_{4(g)}+H_2O_{(g)}\]

This reaction is the reverse of the steam reforming of methane described in Example 14. The reaction is exothermic (ΔH° = −206 kJ/mol), with an equilibrium constant at room temperature of Kp = 7.6 × 1024. Unfortunately, however, CO and H2 do not react at an appreciable rate at room temperature. What conditions would you select to maximize the amount of methane formed per unit time by this reaction?

Given: balanced chemical equation and values of ΔH° and K

Asked for: conditions to maximize yield of product

Strategy:

Consider the effect of changes in temperature and pressure and the addition of an effective catalyst on the reaction rate and equilibrium of the reaction. Determine which combination of reaction conditions will result in the maximum production of methane.

Solution:

The products are highly favored at equilibrium, but the rate at which equilibrium is reached is too slow to be useful. You learned in Chapter 13 that the reaction rate can often be increased dramatically by increasing the temperature of the reactants. Unfortunately, however, because the reaction is quite exothermic, an increase in temperature will shift the equilibrium to the left, causing more reactants to form and relieving the stress on the system by absorbing the added heat. If we increase the temperature too much, the equilibrium will no longer favor methane formation. (In fact, the equilibrium constant for this reaction is very temperature sensitive, decreasing to only 1.9 × 10−3 at 1000°C.) To increase the reaction rate, we can try to find a catalyst that will operate at lower temperatures where equilibrium favors the formation of products. Higher pressures will also favor the formation of products because 4 mol of gaseous reactant are converted to only 2 mol of gaseous product. Very high pressures should not be needed, however, because the equilibrium constant favors the formation of products. Thus optimal conditions for the reaction include carrying it out at temperatures greater than room temperature (but not too high), adding a catalyst, and using pressures greater than atmospheric pressure.

Industrially, catalytic methanation is typically carried out at pressures of 1–100 atm and temperatures of 250°C–450°C in the presence of a nickel catalyst. (At 425°C°C, Kp is 3.7 × 103, so the formation of products is still favored.) The synthesis of methane can also be favored by removing either H2O or CH4 from the reaction mixture by condensation as they form.

Exercise

As you learned in Example 10, the water–gas shift reaction is as follows:

Kp = 0.106 and ΔH = 41.2 kJ/mol at 700 K. What reaction conditions would you use to maximize the yield of carbon monoxide?

Answer: high temperatures to increase the reaction rate and favor product formation, a catalyst to increase the reaction rate, and atmospheric pressure because the equilibrium will not be greatly affected by pressure

Summary

Changing conditions to affect the reaction rates to obtain a single product is called kinetic control of the system. In contrast, thermodynamic control is adjusting the conditions to ensure that only the desired product or products are present in significant concentrations at equilibrium.

Key Takeaway

- Both kinetic and thermodynamic factors can be used to control reaction products.

Conceptual Problems

-

A reaction mixture will produce either product A or B depending on the reaction pathway. In the absence of a catalyst, product A is formed; in the presence of a catalyst, product B is formed. What conclusions can you draw about the forward and reverse rates of the reaction that produces A versus the reaction that produces B in (a) the absence of a catalyst and (b) the presence of a catalyst?

-

Describe how you would design an experiment to determine the equilibrium constant for the synthesis of ammonia:

\[N_{2(g)} + 3H_{2(g)} \rightleftharpoons 2NH_{3(g)}\]

The forward reaction is exothermic (ΔH° = −91.8 kJ). What effect would an increase in temperature have on the equilibrium constant?

-

What effect does a catalyst have on each of the following?

- the equilibrium position of a reaction

- the rate at which equilibrium is reached

- the equilibrium constant?

-

How can the ratio Q/K be used to determine in which direction a reaction will proceed to reach equilibrium?

-

Industrial reactions are frequently run under conditions in which competing reactions can occur. Explain how a catalyst can be used to achieve reaction selectivity. Does the ratio Q/K for the selected reaction change in the presence of a catalyst?

Numerical Problems

-

The oxidation of acetylene via 2C2H2 (g) + 5O2(g) ⇌ 4 CO2(g) + 2 H2O(l) has ΔH° = −2600 kJ. What strategy would you use with regard to temperature, volume, and pressure to maximize the yield of product?

-

The oxidation of carbon monoxide via CO(g) + 1/2 O2(g) ⇌ CO2(g) has ΔH° = −283 kJ. If you were interested in maximizing the yield of CO2, what general conditions would you select with regard to temperature, pressure, and volume?

-

You are interested in maximizing the product yield of the system 2SO2(g) + O2 (g) ⇌ 2 SO3 (g) K = 280 and ΔH° = −158 kJ. What general conditions would you select with regard to temperature, pressure, and volume? If SO2 has an initial concentration of 0.200 M and the amount of O2 is stoichiometric, what amount of SO3 is produced at equilibrium?

Answer

-

Use low temperature and high pressure (small volume).

Contributors

- Anonymous

Modified by Joshua Halpern (Howard University), Scott Sinex, and Scott Johnson (PGCC)

Haber Bosch process videos from BASF and the Royal Society for Chemistry on YouTube

Figure 14.6.3 is from the ESA, now available on the internet wayback machine

Figure 14.6.4 is from the Wikipedia Commons