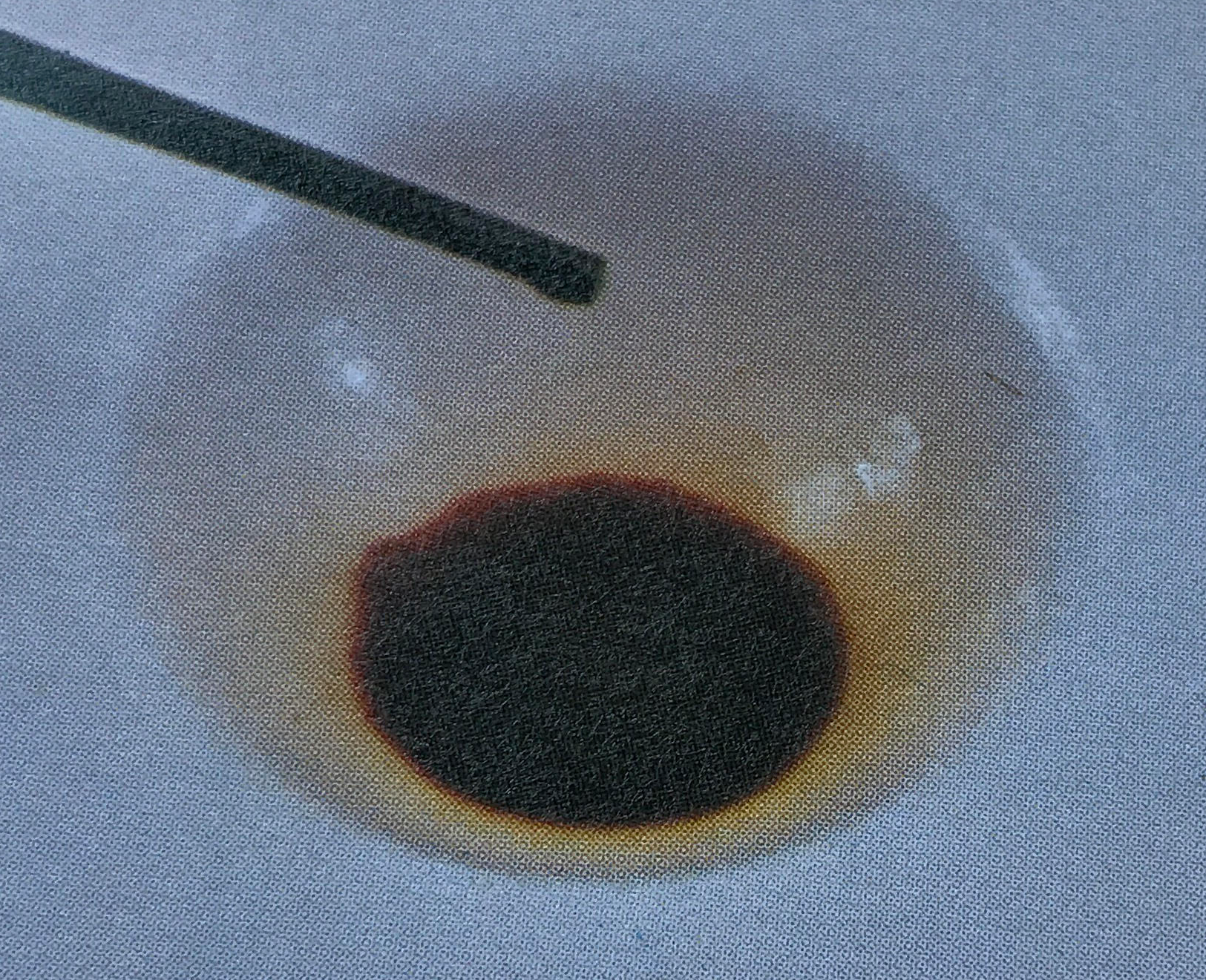

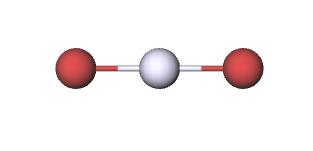

We have presented a microscopic view of the chemical reaction between mercury and bromine. The equation

chemical reaction between mercury and bromine

| \(\ce{Hg(l)^{+}}\) |

\(\ce{Br2(l)} \rightarrow\) |

\(\ce{HgBr2(s)}\) |

|

|

_Bromide_Rotated.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=136&height=94) |

|

|

|

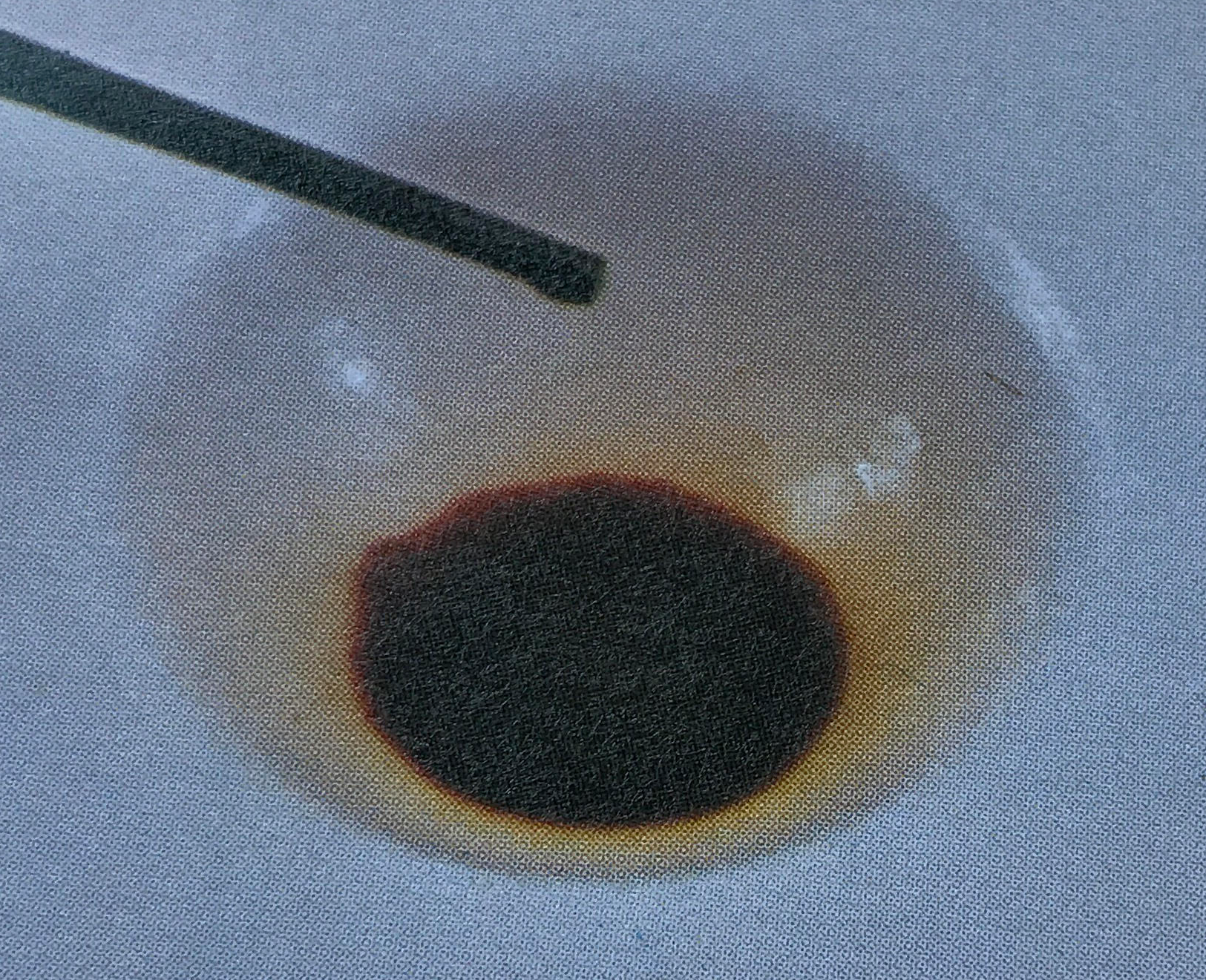

represents the same event in terms of chemical symbols and formulas, while the pictures below represent the macroscopic view. But how does a practicing chemist find out what is occurring on the microscopic scale? When a reaction is carried out for the first time, little is known about the microscopic nature of the products. It is therefore necessary to determine experimentally the composition and formula of a newly synthesized substance.

The first step in such a procedure is usually to separate and purify the products of a reaction. For example, although the combination of mercury with bromine produces mainly mercuric bromide, a little mercurous bromide is often formed as well. A mixture of mercurous bromide with mercuric bromide has properties which are different from a pure sample of HgBr2, and so the Hg2Br2 must be removed. The low solubility of Hg2Br2 in water would permit purification by recrystallization. The product could be dissolved in a small quantity of hot water and filtered to remove undissolved Hg2Br2. Upon cooling and partial evaporation of the water, crystals of relatively pure HgBr2 would form.

Once a pure product has been obtained, it may be possible to identify the substance by means of its physical and chemical properties. The reaction of mercury with bromine yields white crystals which melt at 236°C. The liquid which is formed boils at 322°C. Since it is made by combining two elements, the product is a compound. Comparing its properties with a handbook or table of data leads to the conclusion that it is mercuric bromide.

But suppose you were the first person who ever prepared mercuric bromide. There were no tables which listed its properties then, and so how could you determine that the formula should be HgBr2? One answer involves quantitative analysis—the determination of the percentage by mass of each element in the compound. Such data are usually reported as the percent composition.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Percent Composition

When 10.0 g mercury reacts with sufficient bromine, 18.0 g of a pure compound is formed. Calculate the percent composition from these experimental data.

Solution:

The percentage of mercury is the mass of mercury divided by the total mass of compound times 100 percent:

\[ \%\text{ Hg} = \dfrac{m_{\text{Hg}}}{m_{\text{compound}}} \cdot 100\%\ = \dfrac{\text{10.0 g}}{\text{18.0 g}} \cdot 100\%\text{ = 55.6 }\% \nonumber \]

The remainder of the compound (18.0 g – 10 g = 8.0 g) is bromine:

\[ \%\text{ Br = } \dfrac{m_{\text{Br}}}{m_{\text{compound}}} \cdot \text{ 100 }\%\text{ = } \dfrac{\text{8.0 g}}{\text{18.0 g}} \cdot \text{ 100 } \%\text{ = 44.4 } \% \nonumber \]

As a check, verify that the percentages add to 100:

\[ 55.6\% + 44.4\% = 100\% \nonumber \]

To obtain the formula from percent-composition data, we must find how many bromine atoms there are per mercury atom. On a macroscopic scale this corresponds to the ratio of the amount of bromine to the amount of mercury. If the formula is HgBr2, it not only indicates that there are two bromine atoms per mercury atom, it also says that there are 2 mol of bromine atoms for each 1 mol of mercury atoms. That is, the amount of bromine is twice the amount of mercury. The numbers in the ratio of the amount of bromine to the amount of mercury (2:1) are the subscripts of bromine and mercury in the formula.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\) : Formula

Determine the formula for the compound whose percent composition was calculated in the previous example.

Solution:

For convenience, assume that we have 100 g of the compound. Of this, 55.6 g (55.6%) is mercury and 44.4 g is bromine. Each mass can be converted to an amount of substance

\[\begin{align*} & n_{\text{Hg}}=\text{55.6 g}\cdot \dfrac{\text{1 mol Hg}}{\text{200.59 g}} =\text{0.277 mol Hg} \\ { } \\ & n_{\text{Hg}}=\text{44.4 g}\cdot \dfrac{\text{1 mol Br}}{\text{79.90 g}} =\text{0.556 mol Br} \end{align*} \nonumber \]

Dividing the larger amount by the smaller, we have

\[ \dfrac{n_{\text{Br}}}{n_{\text{Hg}}} = \dfrac{\text{0}\text{.556 mol Br}}{\text{0}\text{.227 mol Hg}} = \dfrac{\text{2}\text{.01 mol Br}}{\text{1 mol Hg}} \nonumber \]

The ratio 2.01 mol Br to 1 mol Hg also implies that there are 2.01 Br atoms per 1 Hg atom. If the atomic theory is correct, there is no such thing as 0.01 Br atom; furthermore, our numbers are only good to three significant figures. Therefore we round 2.01 to 2 and write the formula as HgBr2.

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\): Formula Calculation

A bromide of mercury has the composition 71.5% Hg, 28.5% Br. Find its formula.

Solution:

Again assume a 100-g sample and calculate the amount of each element:

\[\begin{align*} & n_{\text{Hg}}=\text{71}\text{.5 g}\cdot \dfrac{\text{1 mol Hg}}{\text{200.59 g}} = \text{0.356 mol Hg} \\ { } \\ & n_{\text{Hg}}=\text{28.5 g}\cdot \dfrac{\text{1 mol Br}}{\text{79.90 g}} =\text{0.357 mol Br} \end{align*} \nonumber \]

The ratio is

\[ \dfrac{n_{\text{Br}}}{n_{\text{Hg}}} = \dfrac{\text{0.357 mol Br}}{\text{0.356 mol Hg}} = \dfrac{\text{1.00 mol Br}}{\text{1 mol Hg}} \nonumber \]

We would therefore assign the formula HgBr.

The formula obtained in Example \(\PageIndex{3}\) does not correspond to either of the two mercury bromides we have already discussed. Is it a third one? The answer is no because our method can only determine the ratio of Br to Hg. The ratio 1:1 is the same as 2:2, and so our method will give the same result for HgBr or Hg2Br2 (or Hg7Br7, for that matter, should it exist). The formula determined by this method is called the empirical formula or simplest formula. Occasionally, as in the case of mercurous bromide, the empirical formula differs from the actual molecular composition, or the molecular formula. Experimental determination of the molecular weight in addition to percent composition permits calculation of the molecular formula.

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\):

A compound whose molecular weight is 28 contains 85.6% C and 14.4% H. Determine its empirical and molecular formulas.

Solution:

\[\begin{align*} & n_{\text{C}}=\text{85.6 g}\cdot \dfrac{\text{1 mol C}}{\text{12.01 g}} =\text{7.13 mol C} \\ { } \\ & n_{\text{H}}=\text{14.4 g}\cdot \dfrac{\text{1 mol H}}{\text{1.008 g}} =\text{14.3 mol H} \end{align*} \nonumber \]

\[ \dfrac{n_{\text{H}}}{n_{\text{C}}} = \dfrac{\text{14.3 mol H}}{\text{7.13 mol C}} = \dfrac{\text{2.01 mol H}}{\text{1 mol C}} \nonumber \]

The empirical formula is therefore CH2. The molecular weight corresponding to the empirical formula is

\[ 12.01 + 2 \cdot 1.008 = 14.03 \nonumber \]

Since the experimental molecular weight is twice as great, all subscripts must be doubled and the molecular formula is C2H4.

Occasionally the ratio of amounts is not a whole number.

Example \(\PageIndex{5}\): Empirical Formula

Aspirin contains 60.0% C, 4.48% H, and 35.5% O. What is its empirical formula?

Solution:

\[\begin{align*} & n_{\text{H}}=\text{14.4 g}\cdot \dfrac{\text{1 mol H}}{\text{1.008 g}} =\text{14.3 mol H} \\ { } \\& n_{\text{C}}=\text{85.6 g}\cdot \dfrac{\text{1 mol C}}{\text{12.01 g}} =\text{7.13 mol C} \\ { } \\ & n_{\text{O}}=\text{35.5 g}\cdot \dfrac{\text{1 mol O}}{\text{16.00 g}} =\text{2.22 mol O} \end{align*} \nonumber \]

Divide all three by the smallest amount of substance

\[\begin{align*} & \dfrac{n_{\text{C}}}{n_{\text{O}}} = \dfrac{\text{5.00 mol C}}{\text{2.22 mol O}} =\dfrac{\text{2.25 mol H}}{\text{1 mol O}} \\ { } \\ & \dfrac{n_{\text{H}}}{n_{\text{O}}}=\dfrac{\text{4.44 mol H}}{\text{2.22 mol O}}= \dfrac{\text{2.00 mol H}}{\text{1 mol O}} \end{align*} \nonumber \]

Clearly there are twice as many H atoms as O atoms, but the ratio of C to O is not so obvious. We must convert 2.25 to a ratio of small whole numbers. This can be done by changing the figures after the decimal point to a fraction. In this case, .25 becomes \(\small \dfrac{1}{4}\). Thus \( 2.25 = 2 \small\dfrac{1}{4} \normalsize = \tfrac{\text{9}}{\text{4}}\), and

\[ \dfrac{n_{\text{C}}}{n_{\text{O}}} = \dfrac{\text{2.25 mol C}}{\text{1 mol O}} = \dfrac{\text{9 mol C}}{\text{4 mol O}} \nonumber \]

We can also write

\[ \dfrac{n_{\text{H}}}{n_{\text{O}}} = \dfrac{\text{2 mol H}}{\text{1 mol O}} = \dfrac{\text{8 mol H}}{\text{4 mol O}} \nonumber \]

Thus the empirical formula is C9H8O4.

Once someone has determined a formula–empirical or molecular—it is possible for someone else to do the reverse calculation. Finding the weight-percent composition from the formula often proves quite informative, as the following example shows.

Example \(\PageIndex{6}\): Percent Nitrogen

In order to replenish nitrogen removed from the soil when plants are harvested, the compounds NaNO3 (sodium nitrate), NH4NO3 (ammonium nitrate), and NH3 (ammonia) are used as fertilizers. If a farmer could buy each at the same cost per gram, which would be the best bargain? In other words, which compound contains the largest percentage of nitrogen?

Solution

We will show the detailed calculation only for the case of NH4NO3.

1 mol NH4NO3 contains 2 mol N, 4 mol H, and 3 mol O. The molar mass is thus:

\[ M = (2 \cdot 14.01 + 4 \cdot 1.008 + 3 \cdot 16.00) \text{ g} \text{ mol}^{-1} = 80.05 \text{ g} \text{ mol}^{-1} \nonumber \]

A 1-mol sample would weigh 80.05 g. The mass of 2 mol N it contains is:

\[ m_{\text{N}}\text{ = 2 mol N }\cdot \text{ } \dfrac{\text{14.01 g}}{\text{1 mol N}} \text{ = 28.02 g} \nonumber \]

Therefore the percentage of N is:

\[\text{ } \%\text{ N = } \dfrac{m_{\normalsize\text{N}}}{m_{\normalsize\text{NH}_{\text{4}}\text{NO}_{\text{3}}}}\text{ } \cdot \text{ 100 }\%\text{ = } \dfrac{\text{28.02 g}}{\text{80.05 g}}\text{ } \cdot \text{ 100 }\%\text{ = 35}\text{.00 }\%\text{ } \nonumber \]

The percentages of H and O are easily calculated as:

\[\begin{align*} m_{\text{H}}& = \text{4 mol H }\cdot\dfrac{\text{1.008 g}}{\text{1 mol H}}\text{ = 4.032 g} \\ { } \\ \text{ }\%\text{ H } & = \dfrac{\text{4.032 g}}{\text{80.05 g}} \cdot \text{ 100 }\%\text{ = 5.04 }\%\ \\ { } \\ m_{\text{O}}& = \text{3 mol O }\cdot \dfrac{\text{16.00 g}}{\text{1 mol O}} \text{ = 48.00 g} \\ { } \\ \%\text{ O } & = \dfrac{\text{48.00 g}}{\text{80.05 g}}\text{ }\cdot \text{ 100 }\%\text{ = 59.96 }\%\text{ } \end{align*} \nonumber \]

Though not strictly needed to answer the problem, the latter two percentages provide a check of the results. The total \(35.00 + 5.04\% + 59.96\% = 100.00\%\) as it should. Similar calculations for NaNO3 and NH3 yield 16.48% and 82.24% nitrogen, respectively. The farmer who knows chemistry chooses ammonia!

_Bromide_Rotated.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=136&height=94)