Fats and oils are the most abundant lipids in nature. They provide energy for living organisms, insulate body organs, and transport fat-soluble vitamins through the blood.

Structures of Fats and Oils

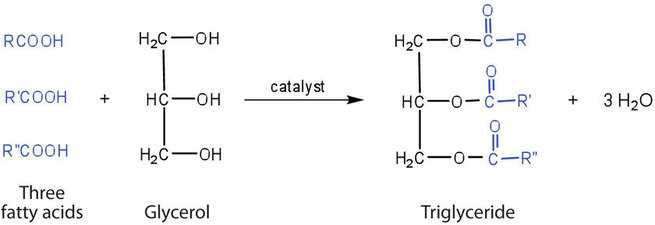

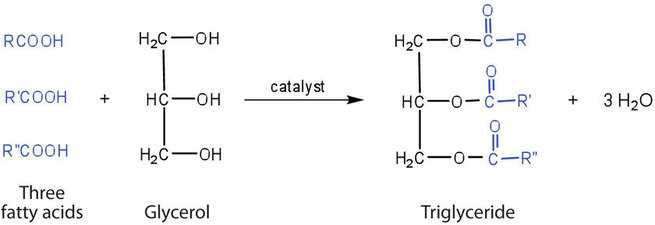

Fats and oils are called triglycerides (or triacylcylgerols) because they are esters composed of three fatty acid units joined to glycerol, a trihydroxy alcohol:

If all three OH groups on the glycerol molecule are esterified with the same fatty acid, the resulting ester is called a simple triglyceride. Although simple triglycerides have been synthesized in the laboratory, they rarely occur in nature. Instead, a typical triglyceride obtained from naturally occurring fats and oils contains two or three different fatty acid components and is thus termed a mixed triglyceride.

Tristearin

a simple triglyceride

a mixed triglyceride

A triglyceride is called a fat if it is a solid at 25°C; it is called an oil if it is a liquid at that temperature. These differences in melting points reflect differences in the degree of unsaturation and number of carbon atoms in the constituent fatty acids. Triglycerides obtained from animal sources are usually solids, while those of plant origin are generally oils. Therefore, we commonly speak of animal fats and vegetable oils.

No single formula can be written to represent the naturally occurring fats and oils because they are highly complex mixtures of triglycerides in which many different fatty acids are represented. Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) shows the fatty acid compositions of some common fats and oils. The composition of any given fat or oil can vary depending on the plant or animal species it comes from as well as on dietetic and climatic factors. To cite just one example, lard from corn-fed hogs is more highly saturated than lard from peanut-fed hogs. Palmitic acid is the most abundant of the saturated fatty acids, while oleic acid is the most abundant unsaturated fatty acid.

Table \(\PageIndex{1}\): Average Fatty Acid Composition of Some Common Fats and Oils (%)*

| |

Lauric |

Myristic |

Palmitic |

Stearic |

Oleic |

Linoleic |

Linolenic |

| Fats |

| butter (cow) |

3 |

11 |

27 |

12 |

29 |

2 |

1 |

| tallow |

|

3 |

24 |

19 |

43 |

3 |

1 |

| lard |

|

2 |

26 |

14 |

44 |

10 |

|

| Oils |

| canola oil |

|

|

4 |

2 |

62 |

22 |

10 |

| coconut oil† |

47 |

18 |

9 |

3 |

6 |

2 |

|

| corn oil |

|

|

11 |

2 |

28 |

58 |

1 |

| olive oil |

|

|

13 |

3 |

71 |

10 |

1 |

| peanut oil |

|

|

11 |

2 |

48 |

32 |

|

| soybean oil |

|

|

11 |

4 |

24 |

54 |

7 |

| *Totals less than 100% indicate the presence of fatty acids with fewer than 12 carbon atoms or more than 18 carbon atoms. |

| †Coconut oil is highly saturated. It contains an unusually high percentage of the low-melting C8, C10, and C12 saturated fatty acids. |

Terms such as saturated fat or unsaturated oil are often used to describe the fats or oils obtained from foods. Saturated fats contain a high proportion of saturated fatty acids, while unsaturated oils contain a high proportion of unsaturated fatty acids. The high consumption of saturated fats is a factor, along with the high consumption of cholesterol, in increased risks of heart disease.

Physical Properties of Fats and Oils

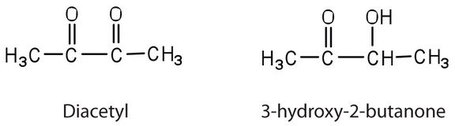

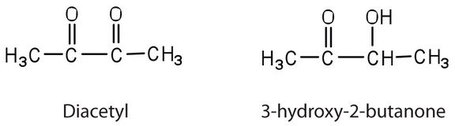

Contrary to what you might expect, pure fats and oils are colorless, odorless, and tasteless. The characteristic colors, odors, and flavors that we associate with some of them are imparted by foreign substances that are lipid soluble and have been absorbed by these lipids. For example, the yellow color of butter is due to the presence of the pigment carotene; the taste of butter comes from two compounds—diacetyl and 3-hydroxy-2-butanone—produced by bacteria in the ripening cream from which the butter is made.

Fats and oils are lighter than water, having densities of about 0.8 g/cm3. They are poor conductors of heat and electricity and therefore serve as excellent insulators for the body, slowing the loss of heat through the skin.

Chemical Reactions of Fats and Oils

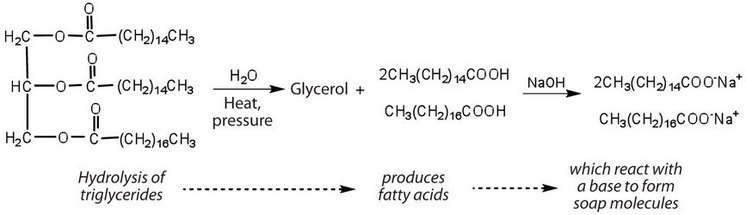

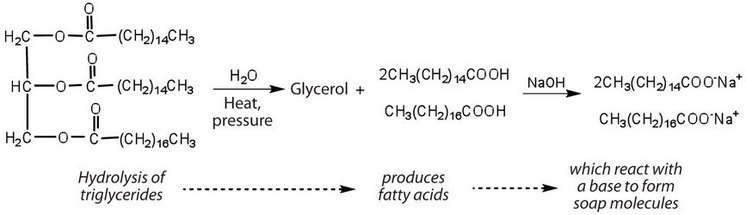

Fats and oils can participate in a variety of chemical reactions—for example, because triglycerides are esters, they can be hydrolyzed in the presence of an acid, a base, or specific enzymes known as lipases. The hydrolysis of fats and oils in the presence of a base is used to make soap and is called saponification. Today most soaps are prepared through the hydrolysis of triglycerides (often from tallow, coconut oil, or both) using water under high pressure and temperature [700 lb/in2 (∼50 atm or 5,000 kPa) and 200°C]. Sodium carbonate or sodium hydroxide is then used to convert the fatty acids to their sodium salts (soap molecules):

Looking Closer: Soaps

Ordinary soap is a mixture of the sodium salts of various fatty acids, produced in one of the oldest organic syntheses practiced by humans (second only to the fermentation of sugars to produce ethyl alcohol). Both the Phoenicians (600 BCE) and the Romans made soap from animal fat and wood ash. Even so, the widespread production of soap did not begin until the 1700s. Soap was traditionally made by treating molten lard or tallow with a slight excess of alkali in large open vats. The mixture was heated, and steam was bubbled through it. After saponification was completed, the soap was precipitated from the mixture by the addition of sodium chloride (NaCl), removed by filtration, and washed several times with water. It was then dissolved in water and reprecipitated by the addition of more NaCl. The glycerol produced in the reaction was also recovered from the aqueous wash solutions.

Pumice or sand is added to produce scouring soap, while ingredients such as perfumes or dyes are added to produce fragrant, colored soaps. Blowing air through molten soap produces a floating soap. Soft soaps, made with potassium salts, are more expensive but produce a finer lather and are more soluble. They are used in liquid soaps, shampoos, and shaving creams.

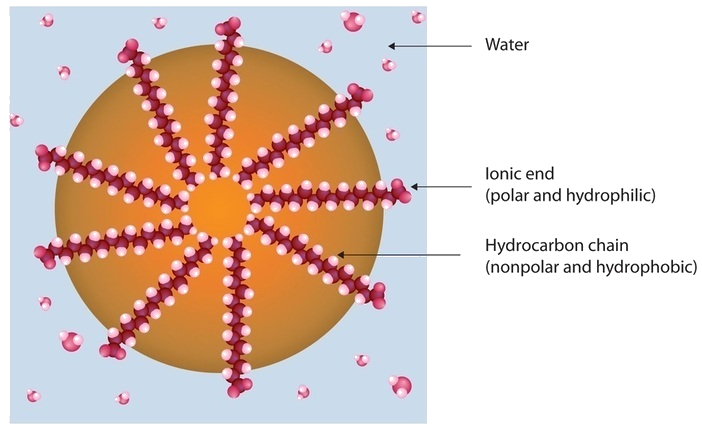

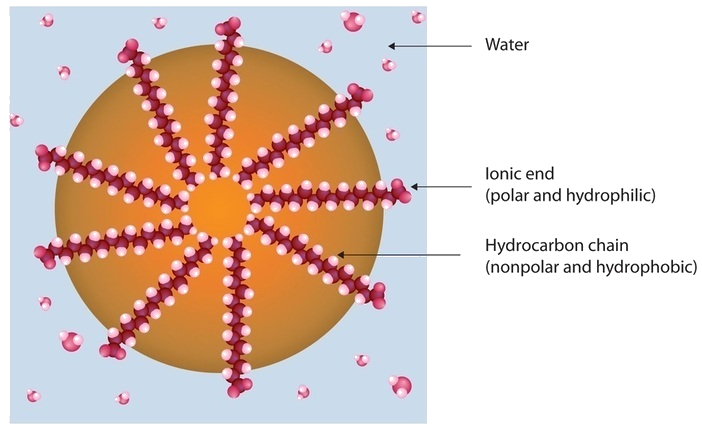

Dirt and grime usually adhere to skin, clothing, and other surfaces by combining with body oils, cooking fats, lubricating greases, and similar substances that act like glues. Because these substances are not miscible in water, washing with water alone does little to remove them. Soap removes them, however, because soap molecules have a dual nature. One end, called the head, carries an ionic charge (a carboxylate anion) and therefore dissolves in water; the other end, the tail, has a hydrocarbon structure and dissolves in oils. The hydrocarbon tails dissolve in the soil; the ionic heads remain in the aqueous phase, and the soap breaks the oil into tiny soap-enclosed droplets called micelles, which disperse throughout the solution. The droplets repel each other because of their charged surfaces and do not coalesce. With the oil no longer “gluing” the dirt to the soiled surface (skin, cloth, dish), the soap-enclosed dirt can easily be rinsed away.

The double bonds in fats and oils can undergo hydrogenation and also oxidation. The hydrogenation of vegetable oils to produce semisolid fats is an important process in the food industry. Chemically, it is essentially identical to the catalytic hydrogenation reaction described for alkenes.

In commercial processes, the number of double bonds that are hydrogenated is carefully controlled to produce fats with the desired consistency (soft and pliable). Inexpensive and abundant vegetable oils (canola, corn, soybean) are thus transformed into margarine and cooking fats. In the preparation of margarine, for example, partially hydrogenated oils are mixed with water, salt, and nonfat dry milk, along with flavoring agents, coloring agents, and vitamins A and D, which are added to approximate the look, taste, and nutrition of butter. (Preservatives and antioxidants are also added.) In most commercial peanut butter, the peanut oil has been partially hydrogenated to prevent it from separating out. Consumers could decrease the amount of saturated fat in their diet by using the original unprocessed oils on their foods, but most people would rather spread margarine on their toast than pour oil on it.

Many people have switched from butter to margarine or vegetable shortening because of concerns that saturated animal fats can raise blood cholesterol levels and result in clogged arteries. However, during the hydrogenation of vegetable oils, an isomerization reaction occurs that produces the trans fatty acids mentioned in the opening essay. However, studies have shown that trans fatty acids also raise cholesterol levels and increase the incidence of heart disease. Trans fatty acids do not have the bend in their structures, which occurs in cis fatty acids and thus pack closely together in the same way that the saturated fatty acids do. Consumers are now being advised to use polyunsaturated oils and soft or liquid margarine and reduce their total fat consumption to less than 30% of their total calorie intake each day.

Fats and oils that are in contact with moist air at room temperature eventually undergo oxidation and hydrolysis reactions that cause them to turn rancid, acquiring a characteristic disagreeable odor. One cause of the odor is the release of volatile fatty acids by hydrolysis of the ester bonds. Butter, for example, releases foul-smelling butyric, caprylic, and capric acids. Microorganisms present in the air furnish lipases that catalyze this process. Hydrolytic rancidity can easily be prevented by covering the fat or oil and keeping it in a refrigerator.

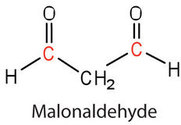

Another cause of volatile, odorous compounds is the oxidation of the unsaturated fatty acid components, particularly the readily oxidized structural unit

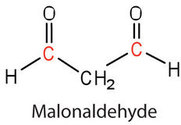

in polyunsaturated fatty acids, such as linoleic and linolenic acids. One particularly offensive product, formed by the oxidative cleavage of both double bonds in this unit, is a compound called malonaldehyde.

Rancidity is a major concern of the food industry, which is why food chemists are always seeking new and better antioxidants, substances added in very small amounts (0.001%–0.01%) to prevent oxidation and thus suppress rancidity. Antioxidants are compounds whose affinity for oxygen is greater than that of the lipids in the food; thus they function by preferentially depleting the supply of oxygen absorbed into the product. Because vitamin E has antioxidant properties, it helps reduce damage to lipids in the body, particularly to unsaturated fatty acids found in cell membrane lipids.