7.3: Cyclic Structures of Monosaccharides

- Page ID

- 431926

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Describe the reaction between and an alcohol and an aldehyde or ketone to form furanose and pyranose rings in monosaccharides.

- Define what is meant by anomers and describe how they are formed.

- Explain what is meant by mutarotation.

Reaction of Aldehyde and Ketone with Alcohol

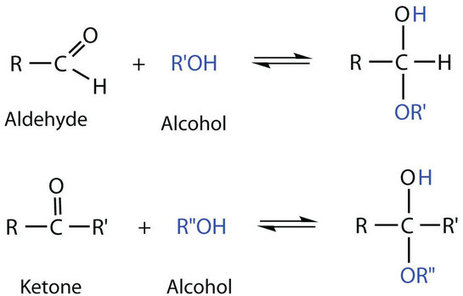

So far we have represented monosaccharides as linear molecules, but many of them also adopt cyclic structures. This conversion occurs because of the ability of aldehydes and ketones to react with alcohols:

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Reaction of aldehyde and ketone with alcohol.

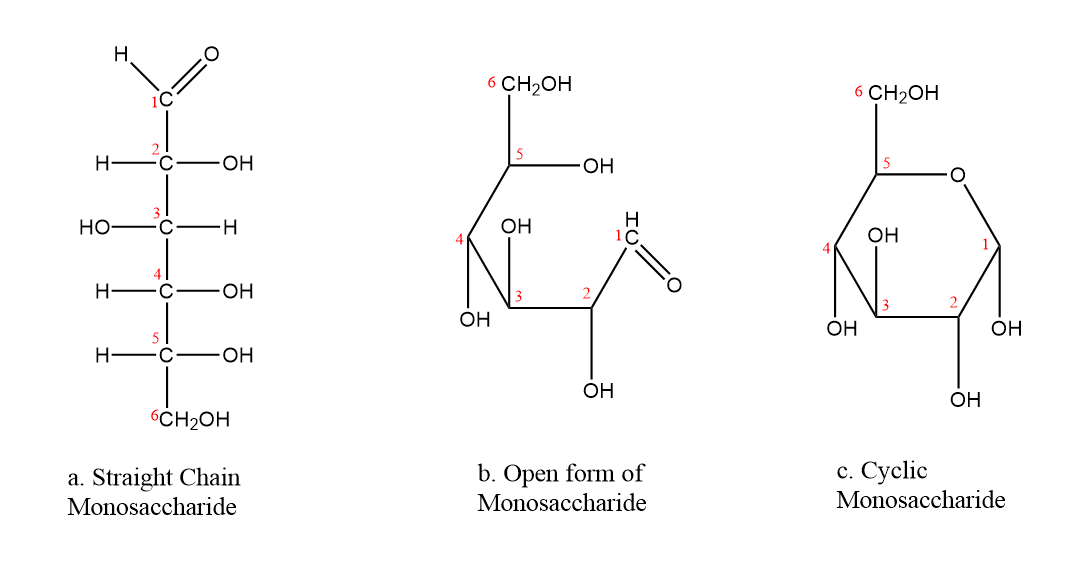

The aldehyde reacts with the OH group on the fifth carbon atom of the monosaccharide as in Figure 7.3.2. Cyclic compounds containing five or six carbon atoms in the ring are the most stable. Therefore, monosaccharides rings consisting of five or six carbon atoms are the most common. Rings that contain five carbons are called furanose and those that contain six carbons are called pyranose.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Cyclization of Glucose: a. Glucose is represented as straight chain, b. Open form of glucose prior to cyclization, c. By reacting the OH group on the fifth carbon atom with the aldehyde group, the cyclic monosaccharide is produced.

Cyclic Structures of Monosaccharides

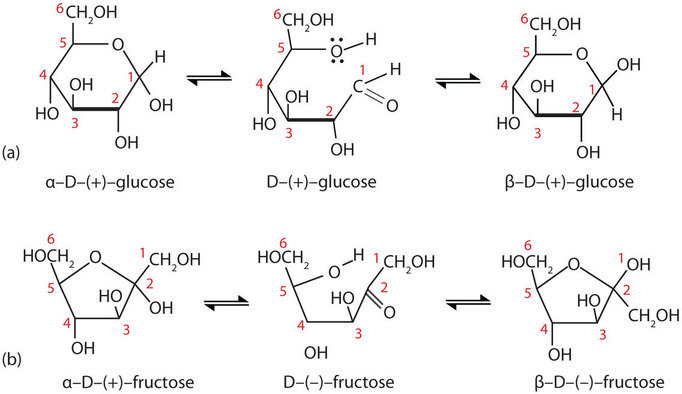

When a straight-chain monosaccharide, such as glucose, forms a cyclic pyranose structure, the carbonyl oxygen atom may be pushed either up or down, giving rise to two isomers, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\). The structure shown on the left side of Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\), with the OH group on the first carbon atom projected downward, represent what is called the alpha (α) form. The structures on the right side, with the OH group on the first carbon atom pointed upward, is the beta (β) form. These two isomers of a cyclic monosaccharide are known as anomers; they differ in structure around the anomeric carbon—that is, the carbon atom that was the carbonyl carbon atom in the straight-chain form.

It is possible to obtain a sample of crystalline glucose in which all the molecules have the α structure or all have the β structure. The α form melts at 146°C, while the β form melts at 150°C. When the sample is dissolved in water, however, a mixture is soon produced containing both anomers as well as the straight-chain form, in dynamic equilibrium (part (a) of Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). You can start with a pure crystalline sample of glucose consisting entirely of either anomer, but as soon as the molecules dissolve in water, they open to form the carbonyl group and then reclose to form either the α or the β anomer. The opening and closing repeats continuously in an ongoing interconversion between anomeric forms and is referred to as mutarotation (Latin mutare, meaning “to change”). At equilibrium, the mixture consists of about 36% α-D-glucose, 64% β-D-glucose, and less than 0.02% of the open-chain aldehyde form.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Monosaccharides. In an aqueous solution, monosaccharides exist as an equilibrium mixture of three forms. The interconversion between the forms is known as mutarotation, which is shown for D-glucose (a) and D-fructose (b).

Even though only a small percentage of the molecules are in the open-chain aldehyde form at any time, the solution will nevertheless exhibit the characteristic reactions of an aldehyde.

The difference between the α and the β forms of sugars may seem trivial, but such structural differences are often crucial in biochemical reactions. This explains why we can get energy from the starch in potatoes and other plants but not from cellulose, even though both starch and cellulose are polysaccharides composed of glucose molecules linked together.

Pentose sugars such as ribose and 2-deoxyribose also exist in furanose cyclic forms shown below:

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): Pentose monosaccharides in their cyclic furanose form.

Summary

Monosaccharides that are pentoses or hexoses form cyclic structures in aqueous solution. Two cyclic isomers can form from each straight-chain monosaccharide; these are known as anomers. In an aqueous solution, an equilibrium mixture forms between the two anomers and the straight-chain structure of a monosaccharide in a process known as mutarotation.