Formal Charge

- Page ID

- 95013

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)A formal charge (FC) is the charge assigned to an atom in a molecule, assuming that electrons in all chemical bonds are shared equally between atoms, regardless of relative electronegativity. When determining the best Lewis structure (or predominant resonance structure) for a molecule, the structure is chosen such that the formal charge on each of the atoms is as close to zero as possible.

The formal charge of any atom in a molecule can be calculated by the following equation:

\[{\displaystyle FC=V-N-{\frac {B}{2}}\ }\]

where V is the number of valence electrons of the neutral atom in isolation (in its ground state); N is the number of non-bonding valence electrons on this atom in the molecule; and B is the total number of electrons shared in bonds with other atoms in the molecule.

Examples

- Example: CO2 is a neutral molecule with 16 total valence electrons. There are three different ways to draw the Lewis structure

- Carbon single bonded to both oxygen atoms (carbon = +2, oxygens = −1 each, total formal charge = 0)

- Carbon single bonded to one oxygen and double bonded to another (carbon = +1, oxygendouble = 0, oxygensingle = −1, total formal charge = 0)

- Carbon double bonded to both oxygen atoms (carbon = 0, oxygens = 0, total formal charge = 0)

Even though all three structures gave us a total charge of zero, the final structure is the superior one because there are no charges in the molecule at all.

Alternative Method

The following is equivalent:

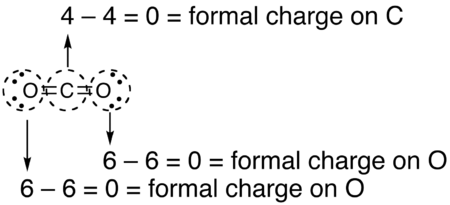

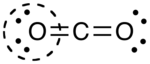

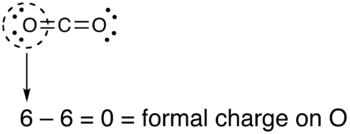

- Draw a circle around the atom for which the formal charge is requested (as with carbon dioxide, below)

- Count up the number of electrons in the atom's "circle." Since the circle cuts the covalent bond "in half," each covalent bond counts as one electron instead of two.

- Subtract the number of electrons in the circle from the group number of the element (the Roman numeral from the older system of group numbering, NOT the IUPAC 1-18 system) to determine the formal charge.

- The formal charges computed for the remaining atoms in this Lewis structure of carbon dioxide are shown below.

It is important to keep in mind that formal charges are just that – formal, in the sense that this system is a formalism. The formal charge system is just a method to keep track of all of the valence electrons that each atom brings with it when the molecule is formed.

Formal charge compared to oxidation state

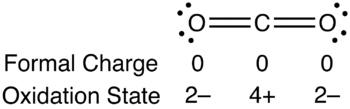

Formal charge is a tool for estimating the distribution of electric charge within a molecule. The concept of oxidation states constitutes a competing method to assess the distribution of electrons in molecules. If the formal charges and oxidation states of the atoms in carbon dioxide are compared, the following values are arrived at:

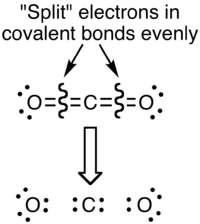

The reason for the difference between these values is that formal charges and oxidation states represent fundamentally different ways of looking at the distribution of electrons amongst the atoms in the molecule. With formal charge, the electrons in each covalent bond are assumed to be split exactly evenly between the two atoms in the bond (hence the dividing by two in the method described above). The formal charge view of the CO2 molecule is essentially shown below:

The covalent (sharing) aspect of the bonding is overemphasized in the use of formal charges, since in reality there is a higher electron density around the oxygen atoms due to their higher electronegativity compared to the carbon atom. This can be most effectively visualized in an electrostatic potential map.

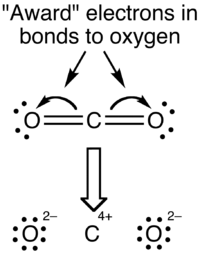

With the oxidation state formalism, the electrons in the bonds are "awarded" to the atom with the greater electronegativity. The oxidation state view of the CO2 molecule is shown below:

Oxidation states overemphasize the ionic nature of the bonding; the difference in electronegativity between carbon and oxygen is insufficient to regard the bonds as being ionic in nature.

In reality, the distribution of electrons in the molecule lies somewhere between these two extremes. The inadequacy of the simple Lewis structure view of molecules led to the development of the more generally applicable and accurate valence bond theory of Slater, Pauling, et al., and henceforth the molecular orbital theory developed by Mulliken and Hund.