2.3: First-Order Reactions

- Page ID

- 1433

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)A first-order reaction is a reaction that proceeds at a rate that depends linearly on only one reactant concentration.

The Differential Representation

Differential rate laws are generally used to describe what is occurring on a molecular level during a reaction, whereas integrated rate laws are used for determining the reaction order and the value of the rate constant from experimental measurements. The differential equation describing first-order kinetics is given below:

\[ Rate = - \dfrac{d[A]}{dt} = k[A]^1 = k[A] \label{1} \]

The "rate" is the reaction rate (in units of molar/time) and \(k\) is the reaction rate coefficient (in units of 1/time). However, the units of \(k\) vary for non-first-order reactions. These differential equations are separable, which simplifies the solutions as demonstrated below.

The Integral Representation

First, write the differential form of the rate law.

\[ Rate = - \dfrac{d[A]}{dt} = k[A] \nonumber \]

Rearrange to give:

\[ \dfrac{d[A]}{[A]} = - k\,dt \nonumber \]

Second, integrate both sides of the equation.

\[ \begin{align*} \int_{[A]_o}^{[A]} \dfrac{d[A]}{[A]} &= -\int_{t_o}^{t} k\, dt \label{4a} \\[4pt] \int_{[A]_{o}}^{[A]} \dfrac{1}{[A]} d[A] &= -\int_{t_o}^{t} k\, dt \label{4b} \end{align*} \]

Recall from calculus that:

\[ \int \dfrac{1}{x} = \ln(x) \nonumber \]

Upon integration,

\[ \ln[A] - \ln[A]_o = -kt \nonumber \]

Rearrange to solve for [A] to obtain one form of the rate law:

\[ \ln[A] = \ln[A]_o - kt \nonumber \]

This can be rearranged to:

\[ \ln [A] = -kt + \ln [A]_o \nonumber \]

This can further be arranged into y=mx +b form:

\[ \ln [A] = -kt + \ln [A]_o \nonumber \]

The equation is a straight line with slope m:

\[mx=-kt \nonumber \]

and y-intercept b:

\[b=\ln [A]_o \nonumber \]

Now, recall from the laws of logarithms that

\[ \ln {\left(\dfrac{[A]_t}{ [A]_o}\right)}= -kt \nonumber \]

where [A] is the concentration at time \(t\) and \([A]_o\) is the concentration at time 0, and \(k\) is the first-order rate constant.

Because the logarithms of numbers do not have any units, the product \(-kt\) also lacks units. This concludes that unit of \(k\) in a first order of reaction must be time-1. Examples of time-1 include s-1 or min-1. Thus, the equation of a straight line is applicable:

\[ \ln [A] = -kt + \ln [A]_o.\label{15} \]

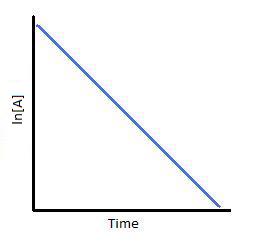

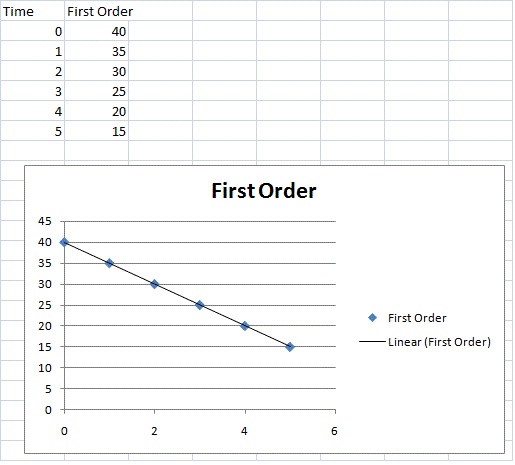

To test if it the reaction is a first-order reaction, plot the natural logarithm of a reactant concentration versus time and see whether the graph is linear. If the graph is linear and has a negative slope, the reaction must be a first-order reaction.

To create another form of the rate law, raise each side of the previous equation to the exponent, \(e\):

\[ \large e^{\ln[A]} = e^{\ln[A]_o - kt} \label{16} \]

Simplifying gives the second form of the rate law:

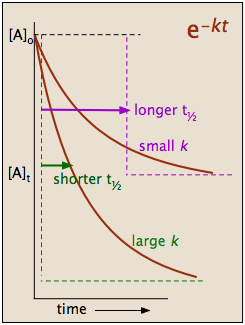

\[ [A] = [A]_{o}e^{- kt}\label{17} \]

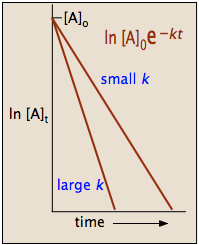

The integrated forms of the rate law can be used to find the population of reactant at any time after the start of the reaction. Plotting \(\ln[A]\) with respect to time for a first-order reaction gives a straight line with the slope of the line equal to \(-k\). More information can be found in the article on rate laws.

This general relationship, in which a quantity changes at a rate that depends on its instantaneous value, is said to follow an exponential law. Exponential relations are widespread in science and in many other fields. Consumption of a chemical reactant or the decay of a radioactive isotope follow the exponential decay law. Its inverse, the law of exponential growth, describes the manner in which the money in a continuously-compounding bank account grows with time, or the population growth of a colony of reproducing organisms. The reason that the exponential function \(y=e^x\) so efficiently describes such changes is that dy/dx = ex; that is, ex is its own derivative, making the rate of change of \(y\) identical to its value at any point.

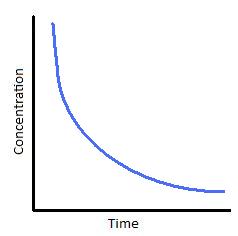

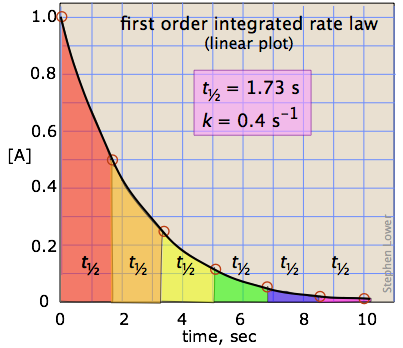

Graphing First-order Reactions

The following graphs represents concentration of reactants versus time for a first-order reaction.

Plotting \(\ln[A]\) with respect to time for a first-order reaction gives a straight line with the slope of the line equal to \(-k\).

Half-lives of first order reactions

The half-life (\(t_{1/2}\)) is a timescale on which the initial population is decreased by half of its original value, represented by the following equation.

\[ [A] = \dfrac{1}{2} [A]_o \nonumber \]

After a period of one half-life, \(t = t_{1/2}\) and we can write

\[\dfrac{[A]_{1/2}}{[A]_o} = \dfrac{1}{2}=e^{-k\,t_{1/2}} \label{18} \]

Taking logarithms of both sides (remember that \(\ln e^x = x\)) yields

\[ \ln 0.5 = -kt\label{19} \]

Solving for the half-life, we obtain the simple relation

\[ t_{1/2}=\dfrac{\ln{2}}{k} \approx \dfrac{0.693}{k}\label{20} \]

This indicates that the half-life of a first-order reaction is a constant.

The half-life of a first-order reaction was found to be 10 min at a certain temperature. What is its rate constant?

SolutionUse Equation 20 that relates half life to rate constant for first order reactions:

\[k = \dfrac{0.693}{600 \;s} = 0.00115 \;s^{-1} \nonumber \]

As a check, dimensional analysis can be used to confirm that this calculation generates the correct units of inverse time.

Notice that, for first-order reactions, the half-life is independent of the initial concentration of reactant, which is a unique aspect to first-order reactions. The practical implication of this is that it takes as much time for [A] to decrease from 1 M to 0.5 M as it takes for [A] to decrease from 0.1 M to 0.05 M. In addition, the rate constant and the half life of a first-order process are inversely related.

If 3.0 g of substance \(A\) decomposes for 36 minutes the mass of unreacted A remaining is found to be 0.375 g. What is the half life of this reaction if it follows first-order kinetics?

Solution

There are two ways to approach this problem: The "simple inspection approach" and the "brute force approach"

Approach #1: "The simple Inspection Approach"

This approach is used when one can recognize that the final concentration of \(A\) is \(\frac{1}{8}\) of the initial concentration and hence three half lives \(\left(\frac{1}{2} \times \frac{1}{2} \times \frac{1}{2}\right)\) have elapsed during this reaction.

\[t_{1/2} = \dfrac{36\, \text{min}}{3}= 12 \; \text{min} \nonumber \]

This approach works only when the final concentration is \(\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^n\) that of the initial concentration, then \(n\) is the number of half lives that have elapsed. If this is not the case, then approach #2 can be used.

Approach #2: "The brute force approach"

This approach involves solving for \(k\) from the integral rate law (Equation \ref{17}) and then relating \(k\) to the \(t_{1/2}\) via Equation \ref{20}. \[\begin{align*} \dfrac{[A]_t}{[A]_o} &= e^{-k\,t} \\[4pt] k &= -\dfrac{\ln \dfrac{[A]_t}{[A]_o}}{t} \\[4pt] &= -\dfrac{\ln \dfrac{0.375\, g}{3\, g}}{36\, \text{min}} \\[4pt] &= 0.0578 \, \text{min}^{-1} \end{align*} \] Therefore, via Equation \ref{20} \[t_{1/2}=\dfrac{\ln{2}}{k} \approx \dfrac{0.693}{0.0578 \, \text{min}^{-1}} \approx 12\, \text{min} \nonumber \]

The first approach is considerably faster (if the number of half lives evolved is apparent).

Calculate the half-life of the reactions below:

- If 4.00 g A are allowed to decompose for 40 min, the mass of A remaining undecomposed is found to be 0.80 g.

- If 8.00 g A are allowed to decompose for 34 min, the mass of A remaining undecomposed is found to be 0.70 g.

- If 9.00 g A are allowed to decompose for 24 min, the mass of A remaining undecomposed is found to be 0.50 g.

- Answer

-

Use the half life reaction that contains initial concentration and final concentration. Plug in the appropriate variables and solve to obtain:

- 17.2 min

- 9.67 min

- 5.75 min

Determine the percent \(\ce{H2O2}\) that decomposes in the time using \(k=6.40 \times 10^{-5} s^{-1}\)

- The time for the concentration to decompose is 600.0 s after the reaction begins.

- The time for the concentration to decompose is 450 s after the reaction begins.

- Answer

-

- Rearranging Eq. 17 to solve for the \([H_2O_2]_t/[H_2O_2]_0\) ratio \[\dfrac{[H_2O_2]_t}{[H_2O_2]_0} = e^{-kt} \nonumber \] This is a simple plug and play application once you have identified this equation. \[\dfrac{[H_2O_2]_{t=600\;s}}{[H_2O_2]_0} = e^{-(6.40 \times 10^{-5} s^{-1}) (600 \, s)} \nonumber \] \[\dfrac{[H_2O_2]_{t=600\;s}}{[H_2O_2]_0} = 0.9629 \nonumber \] So 100-96.3=3.71% of the hydrogen peroxide has decayed by 600 s.

- Rearranging Eq. 17 to solve for the \([H_2O_2]_t/[H_2O_2]_0\) ratio \[\dfrac{[H_2O_2]_t}{[H_2O_2]_0} = e^{-kt} \nonumber \] This is a simple plug and play application once you have identified this equation. \[\dfrac{[H_2O_2]_{t=450\;s}}{[H_2O_2]_0} = e^{-(6.40 \times 10^{-5} s^{-1}) (450 \, s)} \nonumber \] \[\dfrac{[H_2O_2]_{t=450\;s}}{[H_2O_2]_0} = 0.9720 \nonumber \] So 100-97.2=2.8% of the hydrogen peroxide has decayed by 450 s.

References

- Petrucci, Ralph H. General Chemistry: Principles and Modern Applications 9th Ed. New Jersey: Pearson Education Inc. 2007.

Contributors and Attributions

- Rachael Curtis (UCD), Cathy Nguyen (UCD)

Stephen Lower, Professor Emeritus (Simon Fraser U.) Chem1 Virtual Textbook