4.4: The Joule Experiment

- Page ID

- 84311

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Going back to the expression for changes in internal energy that stems from assuming that \(U\) is a function of \(V\) and \(T\) (or \(U(V, T)\) for short)

\[ dU = \left( \dfrac{\partial U}{\partial V} \right)_TdV+ \left( \dfrac{\partial U}{\partial T} \right)_V dT \nonumber \]

one quickly recognizes one of the terms as the constant volume heat capacity, \(C_V\). And so the expression can be re-written

\[ dU = \left( \dfrac{\partial U}{\partial V} \right)_T dV + C_V dT \nonumber \]

But what about the first term? The partial derivative is a coefficient called the “internal pressure”, and given the symbol \(\pi_T\).

\[ \pi_T = \left( \dfrac{\partial U}{\partial V} \right)_T \nonumber \]

James Prescott Joule (1818-1889) recognized that \(\pi_T\) should have units of pressure (Energy/volume = pressure) and designed an experiment to measure it.

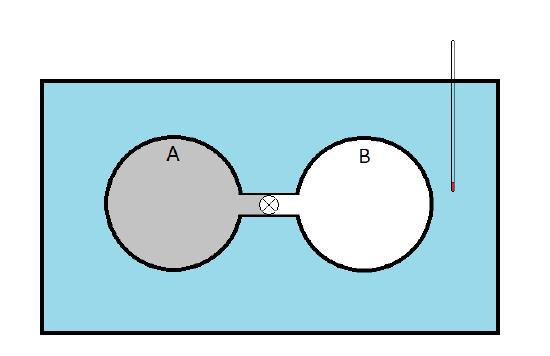

He immersed two copper spheres, A and B, connected by a stopcock. Sphere A is filled with a sample of gas while sphere B was evacuated. The idea was that when the stopcock was opened, the gas in sphere A would expand (\(\Delta V > 0\)) against the vacuum in sphere B (doing no work since \(p_{ext} = 0\). The change in the internal energy could be expressed

\[ dU = \pi_T dV + C_V dT \nonumber \]

But also, from the first law of thermodynamics

\[ dU = dq + dw \nonumber \]

Equating the two

\[ \pi_T dV + C_V dT = dq + dw \nonumber \]

and since \(dw = 0\)

\[ \pi_T dV + C_V dT = dq \nonumber \]

Joule concluded that \(dq = 0\) (and \(dT = 0\) as well) since he did not observe a temperature change in the water bath which could only have been caused by the metal spheres either absorbing or emitting heat. And because \(dV > 0\) for the gas that underwent the expansion into an open space, \(\pi_T\) must also be zero! In truth, the gas did undergo a temperature change, but it was too small to be detected within his experimental precision. Later, we (once we develop the Maxwell Relations) will show that

\[ \left( \dfrac{\partial U}{\partial V} \right)_T = T \left( \dfrac{\partial p}{\partial T} \right)_V -p \label{eq3} \]

Application to an Ideal Gas

For an ideal gas \(p = RT/V\), so it is easy to show that

\[\left( \dfrac{\partial p}{\partial T} \right)_V = \dfrac{R}{V} \label{eq4} \]

so combining Equations \ref{eq3} and \ref{eq4} together to get

\[ \left( \dfrac{\partial U}{\partial V} \right)_T = \dfrac{RT}{V} - p \label{eq5} \]

And since also becuase \(p = RT/V\), then Equation \ref{eq5} simplifies to

\[ \left( \dfrac{\partial U}{\partial V} \right)_T = p -p = 0 \nonumber \]

So while Joule’s observation was consistent with limiting ideal behavior, his result was really an artifact of his experimental uncertainty masking what actually happened.

Appliation to a van der Waals Gas

For a van der Waals gas,

\[ p = \dfrac{RT}{V-b} - \dfrac{a}{V^2} \label{eqV1} \]

so

\[\left( \dfrac{\partial p}{\partial T} \right)_V = \dfrac{R}{V-b} \label{eqV2} \]

and

\[ \left( \dfrac{\partial U}{\partial V} \right)_T = T\dfrac{R}{V-b} - p \label{eqV3} \]

Substitution of the expression for \(p\) (Equation \ref{eqV1}) into this Equation \ref{eqV3}

\[ \left( \dfrac{\partial U}{\partial V} \right)_T = \dfrac{a}{V^2} \nonumber \]

In general, it can be shown that

\[\left( \dfrac{\partial p}{\partial T} \right)_V = \dfrac{\alpha}{\kappa_T} \nonumber \]

And so the internal pressure can be expressed entirely in terms of measurable properties

\[ \left( \dfrac{\partial U}{\partial V} \right)_T = T \dfrac{\alpha}{\kappa_T}-p \nonumber \]

and need not apply to only gases (real or ideal)!