5.4: Optical Activity

- Page ID

- 359589

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The two enantiomers are mirror images of each other. They are very alike and share many properties in common, like same b.p., m.p., density, color, solubility etc. In fact, the pair of enantiomers have the same physical properties except the way they interact with plane-polarized light.

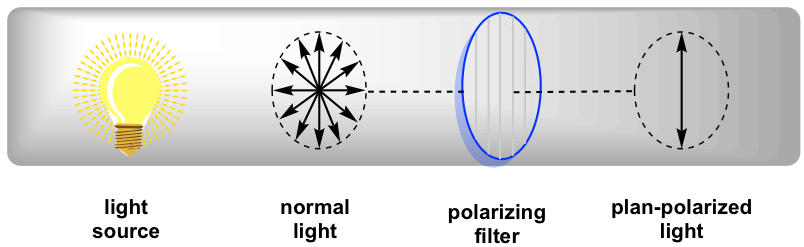

In normal light, the electric filed oscillates in all directions. When normal light passed through a polarizing filter, only light oscillating in one single plane can go through, and the resulting light that oscillates in one single direction is called plane-polarized light.

When plan-polarized light interacts with chiral molecules, the plane of polarization will be rotated by the chiral substances. It was first discovered by Jean-Baptiste Biot in 1815 that some naturally occurring organic substances, like camphor, is able to rotate the plane of polarization of plane-polarized light. He also noted that some compounds rotated the plane clockwise and others counterclockwise. Further studies indicate that the rotation is caused by the chirality of substances.

The property of a compound being able to rotate the plane of polarization of plane-polarized light is called the optical activity, and the compound with such activity is labelled as optical active. The stereoisomer that is optical active is also called as optical isomer.

Chiral compound is optical active. Achiral compound is optical inactive.

The sample containing a chiral compound rotates the plane of polarization of plane-polarized light, the direction and angles of the rotation depends on the nature and concentration of the chiral substances. The rotation angles can be measured by using polarimeter (later in this section).

For a pair of enantiomers with same concentration, under the same condition, they rotate the plane of polarization with the same angles but in opposite direction, one is clockwise and the other is counterclockwise.

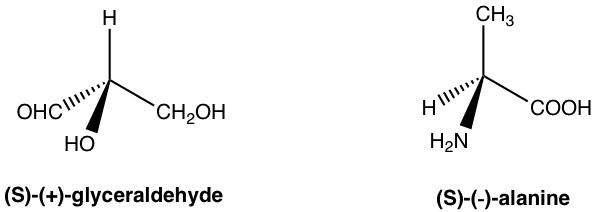

The enantiomer rotates the plane of polarization clockwise is said to be dextrorotatory (Latin, means to the right), and labelled with the prefix (d) or (+). The enantiomer rotates the plane of polarization counterclockwise is said to be levorotatory (Latin, means to the left), and labelled with the prefix (l) or (–). The d/l (or +/-) indicate the direction in which an optical active compound rotates the plane of polarization of plan-polarized light, that has to be determined by experiment to measure the optical rotation. d/l (or +/–) symbol has nothing to do with R/S. R/S indicates the arrangement of the groups around the chirality center, that can be determined by knowing the exact spatial arrangement of the groups. That means compound with R configuration can be either d or l, and compound with S configuration can also be either d or l. For the examples below, both compounds are S-isomer, but one is d (+) and the other is l (-).

The only thing we can be sure is that for a pair of enantiomers, if one enantiomer has been determined as d, then the other enantiomer must be l, and vice versa.

Measurement of Optical Rotation

Polarimeter is the instrument that measures the direction and angles of rotation of plane-polarized light. The plane-polarized light pass through the sample tube containing the solution of sample, and the angle of rotations will be received and recorded by the analyzer, as summarized in Fig. 5.4c.

Since the measurement results vary with the wavelength of the light being used, the specific light from a sodium atomic spectrum with the wavelength of 589 nm, which is called the sodium D-line, is used for most polarimeter. The rotation degree measured by the polarimeter is called the observed rotation (α), and the observed rotation depends on the length of the sample tube, concentration of the sample and temperature.

To compare the optical rotation between different compounds under consistent conditions, the specific rotation ![]() is used. Specific rotation is the rotation caused by a solution with concentration of 1.0 g/mL in a sample tube of 1.0 dm length. The temperature is usually at 20°C. Based on this definition, the specific rotation can be calculated from the observed rotation by applying the formula:

is used. Specific rotation is the rotation caused by a solution with concentration of 1.0 g/mL in a sample tube of 1.0 dm length. The temperature is usually at 20°C. Based on this definition, the specific rotation can be calculated from the observed rotation by applying the formula:

Please note: In this formula, the unit of concentration (g/mL) and length of the sample tube (dm) are not the units we are familiar with. Also, the unit of the specific rotation is in degree (°), don’t need to worry about the units cancellation in this formula.

Examples: Calculate the specific rotation

The observed rotation of 10.0g of (R)-2-methyl-1-butnaol in 50mL of solution in a 20-cm polarimeter tube is +2.3° at 20 °C, what is the specific rotation of the compound?

Solution

Specific rotation is the characteristic property of an optical active compound. The literature specific rotation values of the authentic compound can be used to confirm the identity of an unknown compound. For the example here, if it has been measured that the specific rotation of ( R )-2-methyl-1-butnaol is +5.75 ° , then we can tell that the other enantiomer ( S )-2-methyl-1-butnaol must have the specific rotation of -5.75 ° , without further measurement necessary.

Optical Activity of Different Samples

When a sample under measurement only contain one enantiomer, this sample is called as enantiomerically pure, means only one enantiomer is present in the sample.

The sample may also consists of a mixture of a pair of enantiomers. For such mixture sample, the observed rotation value of the mixture, together with the information of the specific rotation of one of the enantiomer allow us to calculate the percentage (%) of each enantiomer in the mixture. To do such calculation, the concept of enantiomer excess (ee) will be needed. The enantiomeric excess (ee) tells how much an excess of one enantiomer is in the mixture, and it can be calculated as:

We will use a series of hypothetic examples in next table for detailed explanation.

| If the specific rotation of a (+)-enantiomer is +100°, then the observed rotation of the following samples are (assume the sample tube has the length of 1 dm, and the concentration for each sample is 1.0 g/mL): | ||

| Sample Number |

Sample |

Observed rotation (º) |

| 1 | pure (+) enantiomer | +100 |

| 2 | Pure (-)-enantiomer | -100 |

| 3 | Racemic mixture of 50% (+)-enantiomer

and 50% (-)-enantiomer |

0 |

| 4 | Mixture of 75% (+)-enantiomer and 25% (-)-enantiomer |

+50 |

| 4 |

Mixture of 20% (+)-enantiomer and 80% (-)-enantiomer

|

-60 |

Sample #1 and #2 are straightforward.

Sample #3 is for a mixture with equal amount of two enantiomers, and such mixture is called racemic mixture or racemate. Racemic mixtures do not rotate the plane of polarization of plane-polarized light, that means racemic mixtures are optical inactive and have the observed rotation of zero! This is because that for every molecule in the mixture that rotate the plane of polarization in one direction, there is an enantiomer molecule that rotate the plan of polarization in the opposite direction with the same angle, and the rotation get cancelled out. As a net result, no rotation is observed for the overall racemic mixture. The symbol (±) sometimes is used to indicate a mixture is racemic mixture.

Sample #4, the (+)-enantiomer is in excess. Since there are 75% (+)-enantiomer and 25%(-)-enantiomer, the enantiomeric excess (ee) value of (+)-enantiomer is 75% – 25% = 50%, this can also be calculated by the formula: ee =

In this sample of mixture, the rotation of the (-)-enantiomer is cancelled by the rotation caused by part of the (+)-enantiomer, so the overall net observed rotation depends on how much “net amount” of (+)-enantiomer present. This can be shown by the diagram below that helps to understand.

Sample #5, the (-)-enantiomer is in excess, and because there is 80% (-)-enantiomer and 20% (+)-enantiomer, the enantiomeric excess (ee) value of (-)-enantiomer is 80% – 20% = 60%, this can also be calculated by the formula: ee =

Please note: to calculate the e.e value, it is not necessary to include the sign of the rotation angle, as long as keep in mind that the sign (+ or –) of the observed rotation indicates that which enantiomer is in excess.

Exercises 5.6

Answers to Practice Questions Chapter 5

Examples: An advanced level of calculation

The (+)-enantiomer of a compound has specific rotation ([α]20D) of +100°. For a sample (1 g/ml in 1dm cell) that is a mixture of (+) and (-) enantiomers, the observed rotation α is -45°, what is the percentage of (+) enantiomer present in this sample?

Solution

The observed rotation is in “-”, so (-)-enantiomer is in excess.

ee of (-)-enantiomer is:

From here, we will see two ways of solving such type of question:

Method I: solving algebra

% of (-)-enantiomer is set as “x”; % of (+)-enantiomer is set as “y”

x + y = 100%

x – y = 45%

Solve x = 72.5%; y = 27.5%;

So there is 72.5% (-)-enantiomer and 27.5% of (+)-enantiomer in the sample.

Method II: using diagram, the answer is in blue color, there is 27.5% of (+)-enantiomer.

Chirality and Biological Properties

Other than optical activity difference, the different enantiomers of a chiral molecule usually show different properties when interacting with other chiral substances. This can be understood by using the analogue example of fitting a hand into the respective glove: right hand only fits into right glove, and it feels weird and uncomfortable if you wear left glove on the right hand. This is because both right hand and right glove are chiral. A chiral object only fit into a specific chiral environment.

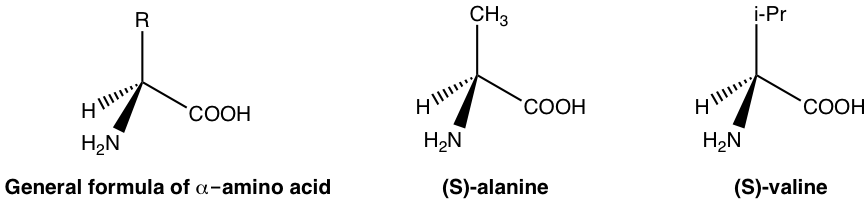

In human body, the biological functions are modulated by a lot of enzymes and receptors. Enzymes and receptors are essentially proteins, and proteins are made up of amino acids. Amino acids are examples of naturally exist chiral substances. With the general formula given below, the carbon with amino (NH2) group is the chirality (asymmetric) center for most amino acids, and only one enantiomer (usually S-enantiomer) exist in nature. A few examples of amino acids are given below with the general formula.

Because amino acids are chiral, proteins are chiral so enzymes and receptors are chiral as well. The enzyme or receptor therefore form the chiral environment in human body that distinguish between R or S enantiomer. Such selectivity can be illustrated by the simple diagram below.

The binding site of enzyme or receptor is chiral, so it only binds with the enantiomer whose groups are in the proper positions to fit into the binding site. As shown in the diagram, only one enantiomer binds with the site, but not the other enantiomer.

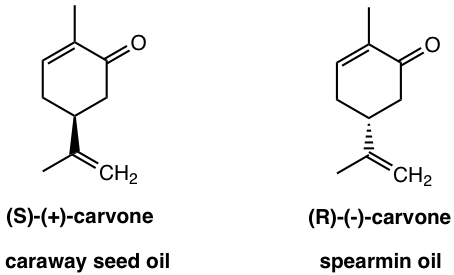

A couple of common examples to showcase such binding selectivity of different enantiomer may include limonene and carvone.

Limonene has two enantiomers, and they smell totally different to human being because they interact with different receptors that located on the nerve cells in nose. The (R)-(+)-limonene is responsible for the smell of orange, and the (S)-(-)-limonene gives the bit smell of lemon.

If you like caraway bread, that is due to the (S)-(+)-carvone; and the (R)-(-)-carvone that is found in spearmint oil gives much different odor.

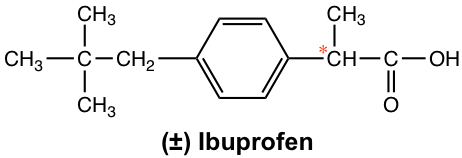

More dramatic examples of how chirality plays important role in biological properties are found in many medicines. For the common over-counter anti-inflammatory drug ibuprofen (Advil), for example, only (S)-enantiomer is the active agent, while the (R)-enantiomer has no any anti-inflammatory action. Fortunately, the (R)-enantiomer does not have any harmful side effect and slowly converts to the (S)-enantiomer in the body. The ibuprofen is marketed usually as a racemate form.

The issue of chiral drugs (the drug contain a single enantiomer, not as a racemate) was not in the attention of drug discovery industry until 1960. Back then, drugs were approved in racemate form if a chirality center involved, and there was no further study about biological difference on different enantiomers. These were all changed by the tragic incident of thalidomide. Thalidomide was a drug that was sold in more than 40 countries, mainly in Europe, in early 1960s as a sleeping aid and to pregnant women as antiemetic (drug that preventing vomiting) to combat morning sickness. It was not recognized at that time that only the R-enantiomer has the property, while the S-enantiomer was a teratogen that causes congenital deformations. The drug was marketed as a racemic mixture and caused about 10,000 children had been damaged until it was withdrawn from the market in Nov. 1961. This drug was not approved in US however, attributed to Dr. Frances O. Kelsey, who was a physician for the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) at that time and had insisted on addition tests on some side effects. Thousands of life were saved by Dr. Kelsey, and she was awarded the President’s medal in 1962 for preventing the sale of thalidomide.