7.3: Overview of Functional Groups Based on Atom Hybridization

- Page ID

- 215704

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)I. HYDROCARBONS

- Substances containing only carbon and hydrogen.

| Alkanes | C-C | Only sp3 carbon present (technically not a functional group) |

| Alkenes | C=C | At least one \(\pi\) -bond between two sp2 carbons present |

| Alkynes | C \(\equiv\) C | At least one triple bond between two sp carbons present |

II. ALKYL HALIDES, OR HALOALKANES

- Substances containing at least one C-X bond, where X=F, Cl, Br, or I.

ALKYL FLUORIDES C-F

ALKYL BROMIDES C-Br

ALKYL CHLORIDES C-Cl

ALKYL IODIDES C-I

III. GROUPS CONTAINING OXYGEN

- Both carbon and oxygen can be sp3 or sp2 hybridized, or a combination of both.

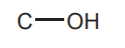

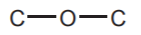

ALCOHOLS  and ETHERS

and ETHERS  sp3 Oxygen

sp3 Oxygen

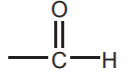

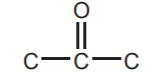

ALDEHYDES  and KETONES

and KETONES  sp2 Oxygen

sp2 Oxygen

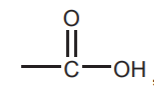

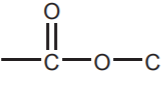

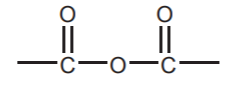

CARBOXYLIC ACIDS  , ESTERS

, ESTERS  , and ANHYDRIDES

, and ANHYDRIDES

These functional groups contain both sp3 and sp2 oxygen.

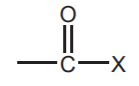

ACID, OR ACYL HALIDES  The most common halogens used are chlorine and bromine

The most common halogens used are chlorine and bromine

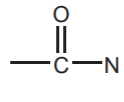

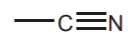

IV. GROUPS CONTAINING NITROGEN

- They may also contain other elements. For example amides also contain oxygen

AMINES  (sp3 Nitrogen), AMIDES

(sp3 Nitrogen), AMIDES  and NITRILES

and NITRILES  (sp Nitrogen)

(sp Nitrogen)

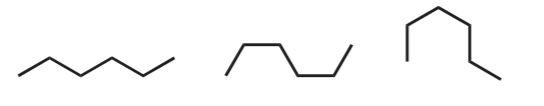

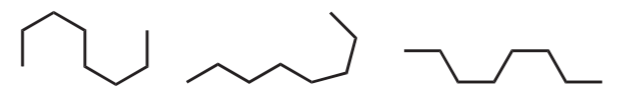

Before proceeding, it is important to emphasize that beginning organic chemistry students must get used to seeing alkane chains from different angles, perspectives, and positions, as shown below using line-angle formulas for linear alkanes.

Hexane

Octane

BRANCHED ALKANES and ALKYL GROUPS.

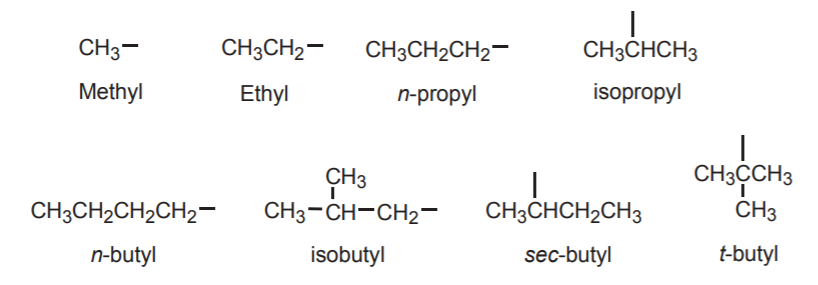

When naming branched alkanes by IUPAC rules, identify and name the longest continuous carbon chain first. Then identify the branch, or branches. The branches are called alkyl groups. For example, a one carbon branch is called a methyl group. The names of alkyl groups are the same as those of analogous alkanes, except that their names end in -yl, instead of -ane. The following are examples of the most common alkyl groups encountered in introductory organic chemistry courses. Alky groups never exist by themselves. In alkanes they are always attached to a higher priority chain and are therefore sometime called substituents. The point of attachement is indicated by a dash.

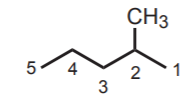

In the following example, the longest continuous carbon chain has five carbons. Therefore the parent alkane is pentane. There is a methyl group attached to this chain. The molecule is then named methylpentane. Finally, the exact position of the methyl group is specified by numbering the main chain from the end closest to the methyl group. The complete IUPAC name for this alkane is 2-methylpentane.

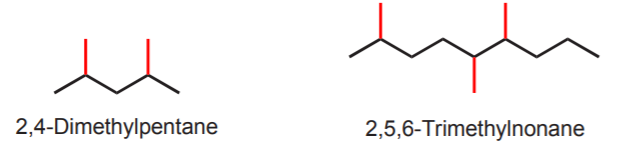

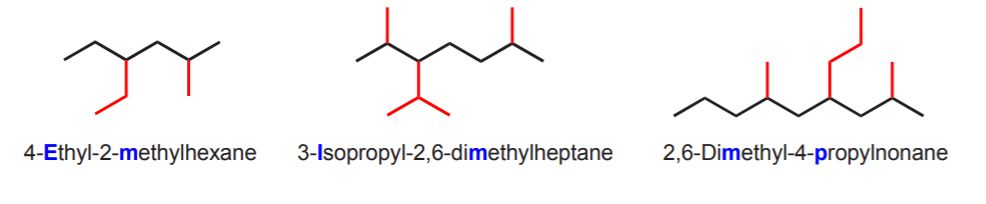

In the following examples the alkyl groups are shown in red. Students must get used to line-angle formulas as early as possible.

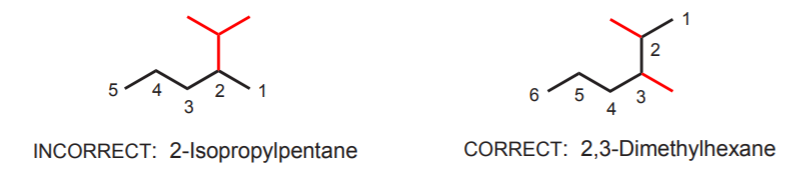

Make sure you’ve identified the longest continuous carbon chain correctly. Otherwise you might end up with the wrong name. The longest continuous carbon chain doesn’t always have to be a horizontal row of carbons. It can take twists and turns. That’s why one must get used to visualize molecules from different angles and perspectives. The following example illustrates the correct name and an incorrect name based on a horizontal row of carbons.

The correct name above illustrates what’s done when there are several substituents of the same kind. First identify their positions, then use the prefixes di-, tri-, tetra-, etc. to indicate how many are present.

If there are substituents of different kinds present, name them in alphabetical order (e.g. ethyl before methyl). Prefixes such as di-, tri-, tetra-, etc. are ignored when alphabetizing.

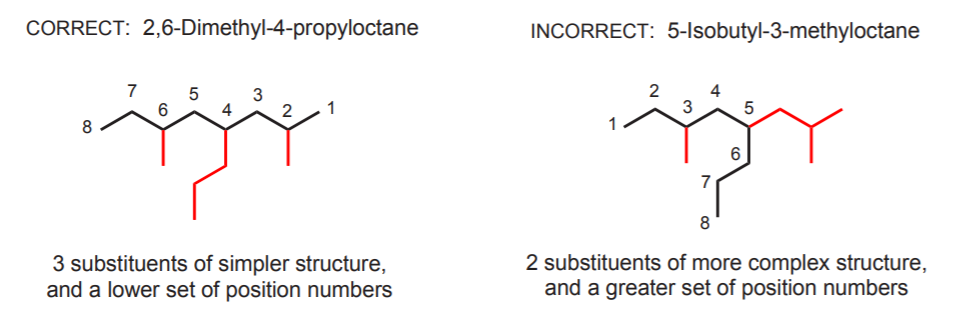

If there are several options for choosing the longest continuous carbon chain, choose the one that yields the simplest name. That means:

(a) The longest continuous carbon chain has the greatest number of substituents, and

(b) The name has the lowest set of numbers indicating the substituent positions.

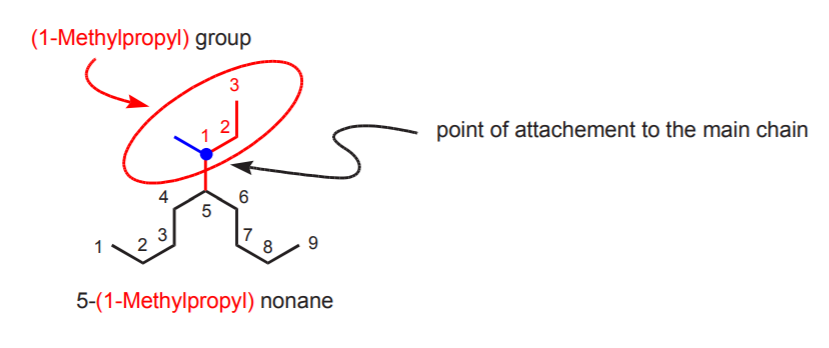

Complex alky groups (those which are branched themselves) are named as if they were alkanes, but the name ends in -yl and is enclosed in parenthesis. The carbon from which the substituent atttaches to the main chain is automatically number 1.

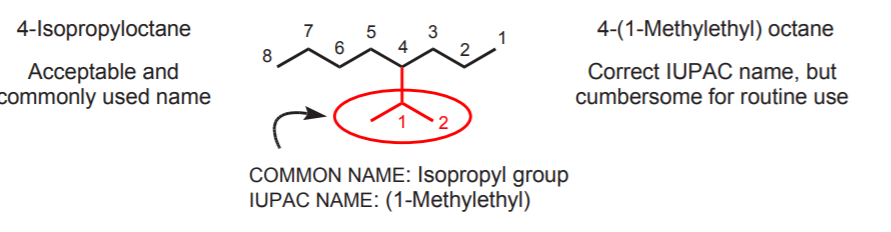

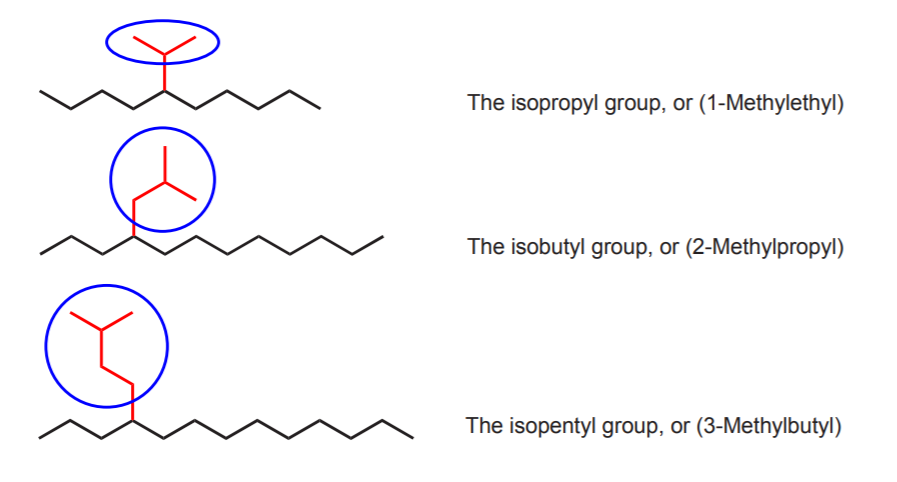

Although common alkyl group names such as isopropyl and t-butyl are commonly used as part of IUPAC names, strict IUPAC rules call for naming them as complex substituents. Common names are used because they are easier to say, shorter, and save paper and ink in scientific publications when they have to be used repeatedly in manuscripts.

ALKANES: COMMON NAMES

Like alkyl groups, alkanes can also have common names. Common, or “trivial” names are rarely used for straight chain alkanes, but are frequently used for branched alkanes. The following pages contain some terminology that organic chemistry students must memorize or become familiar with, due to the fact that it is widely used in textbooks and in the chemical literature.

ISOALKANES and ISOALKYL GROUPS

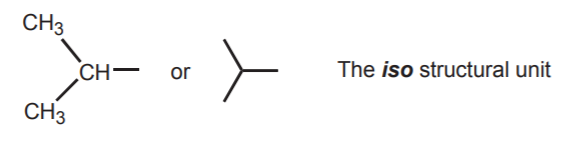

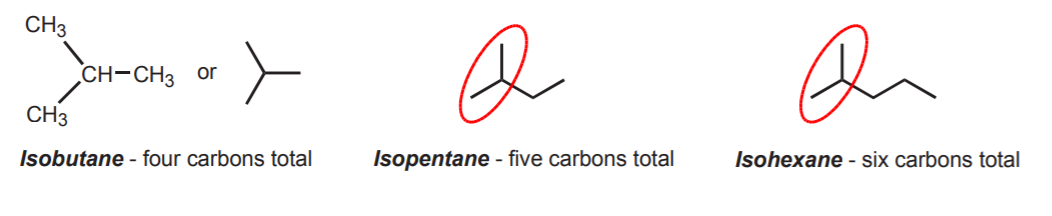

The iso structural unit consists of two methyl groups attached to a common carbon. When this unit is present in an alkane or alky group, the common name starts with the prefix iso.

When this unit is present in alkanes, the molecule is named according to the total number of carbon atoms present, but the name starts with the prefix iso. The smallest possible isoalkane is then isobutane.

The same rules apply to isoalkyl groups, but their names end in -yl. The smallest possible isoalky group is the isopropyl group, because alkyl groups are always attached to another carbon chain.

PRIMARY, SECONDARY, AND TERTIARY CARBONS.

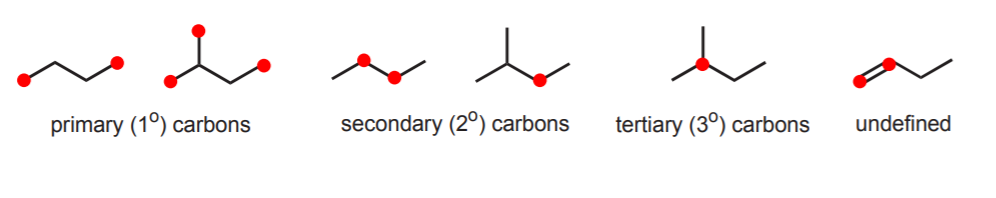

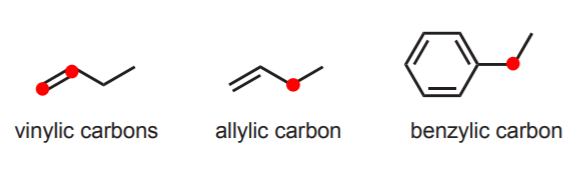

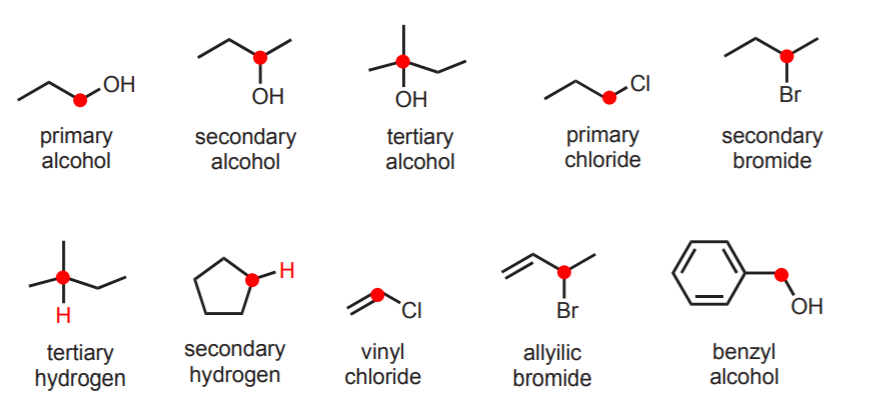

Another bit of terminology associated with common names refers to the connectivity of sp3 carbons in alkanes and alkyl groups. A primary carbon is one that is covalently attached to only one other carbon. A secondary carbon is one attached to two other carbons. A tertiary carbon is attached to three other carbons. This definition implies that methane cannot have any such carbons, since it consists of only one carbon atom. Likewise, this terminology applies only to sp3 carbons. Other types are not defined in this way. In the following examples the carbons in question are indicated as dots.

The carbon atoms directly engaged π-bonding in alkenes are referred to as vinylic. An sp3 carbon directly attached to a vinylic carbon is referred to as allylic. Finally, an sp3 carbon directly attached to a benzene ring is referred to as benzylic.

Although it is emphasized that this is terminology used in common names, it is widely used and therefore important. It constitutes the basis for characterizing not only alkanes, but also other types of compounds where the main functionality is attached to a carbon that belongs to one of the types described. Thus we can have primary alcohols, secondary chlorides, allylic hydrogens, etc. based on the type of carbon to which they are attached.

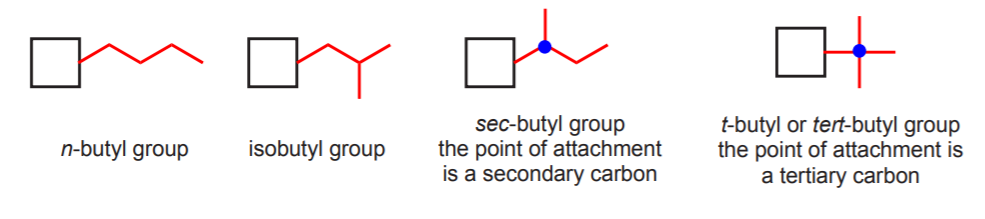

This terminology is also used to identify the point of attachment of certain alkyl groups to the main chain of a molecule, based on the type of carbon from which the alkyl group connects to the main chain. For example four different butyl groups are possible, depending on their structure and their point of attachemnt to the main carbon chain. Two of them are named sec-butyl and tert-butyl (or t-butyl) because they connect to the main chain from a secondary and a tertiary carbon respectively.

The square represents the main carbon chain of a molecule

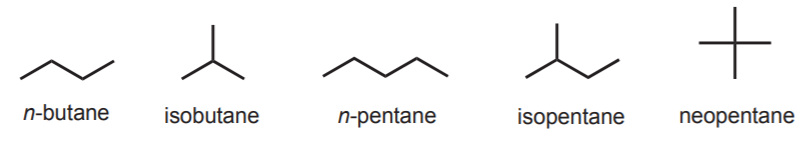

While there are four possible butyl groups, only two possible butanes exist. They are n-butane and isobutane (once again, these are common names). Likewise, there are three possible pentanes called n-pentane, isopentane, and neopentane.

The nomenclature concepts presented in the previous sections also apply to cycloalkanes. Please consult your organic chemistry textbook for examples and additional practice exercises.