5.3: Cyclic structures of monosaccharides

- Page ID

- 423679

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Draw and inter-convert open-chain and cyclic hemiacetal forms of compounds containing carbonyl and alcohol groups in the same molecule.

- Convert Fisher projections to Howarth projections and to chair conformation in the cases of pyranose forms of monosaccharides.

- Define Howarth projection, anomeric carbon, \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) configuration of the anomeric carbon, furanose, and pyranose forms, and mutarotation of monosaccharides.

Cyclic hemiacetal

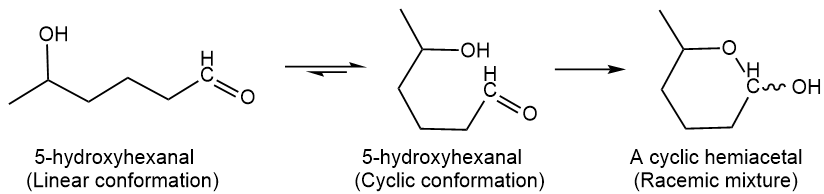

Alcohol (\(\ce{R-OH}\)) and a carbonyl (\(\ce{C=O}\)) groups react with each other and form a hemiacetal group. The hemiacetals are usually unstable and revert to the reactants. However, suppose the alcohol and the carbonyl groups are on the same molecule and can react to form a five- or six-member cyclic hemiacetal. The product is more stable than the reactants, as shown in the following example reaction.

Note that the hemiacetal \(\ce{C}\) is a new chiral center that is produced as a racemic mixture, which is represented by a wavy line in the \(\ce{-OH}\) group. Monosaccharides are polyhydroxy aldehydes or polyhydroxy ketones that often exist as hemiacetal as the dominant form in equilibrium with the open-chain form, as described in the next section.

Fisher projections to Haworth projections

Fisher projections represent the open-chain forms of monosaccharides where the \(\ce{C}\)-chain is a vertical line. Hemiacetals are five or six-member ring structures represented by pentagon or hexagon shapes.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) explains the steps to re-draw Fisher projection in cyclic conformation.

- Rotate the Fisher projection by 90o clockwise from vertical to horizontal orientation. The groups on the right of Fisher's projection end up above, and those to the left end below in the horizontal orientation.

- Move \(\ce{C's}\)#1, 4, 5, and 6 up by 60o each to arrive at the cyclic open-chain conformation#1.

- Rotate the \(\ce{C}\)4-\(\ce{C}\)5 bond by 60o counterclock wise to bring the \(\ce{C}\)#5\(\ce{-OH}\) group in the cycle of \(\ce{C's}\) and \(\ce{C}\)#6 pointing above, i.e., cyclic conformation#1 in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\).

- \(\ce{C}\)#5\(\ce{-OH}\) and a carbonyl (\(\ce{C=O}\)) of \(\ce{C}\)#1 react to produce the hemiacetal group with the new \(\ce{-OH}\) group on \(\ce{C}\)#1 either pointing away from the hemiacetal \(\ce{O}\), i.e., \(\alpha\)- or point towards the hemiacetal \(\ce{O}\), i.e., \(\beta\)-orientation in the cyclic hemiacetal.

\(\ce{C}\)he \(\ce{C}\)\(\ce{C=O}\)\(\ce{C}\)\(\ce{C}\)#1is the anomeric \(\ce{C}\)

five or six-membered cyclic hemiacetals of monosaccharides, presented as pentagon or hexagon shape. It is viewed through its edge perpendicular to the plane of the page, such that the anomeric \(\ce{C}\)

Conversion of monosaccharides from open chain to cyclic hemiacetal produced a new chiral center at the anomeric \(\ce{C}\). It is a mixture of two conformations: the \(\ce{-OH}\) group on anomeric \(\ce{C}\) going away from the is \(\alpha\)- and towards it is \(\beta\)-configuration, as illustrated in the figure on the right with the help of D-glucose example.

Conversion of monosaccharides from open chain to cyclic hemiacetal produced a new chiral center at the anomeric \(\ce{C}\). It is a mixture of two conformations: the \(\ce{-OH}\) group on anomeric \(\ce{C}\) going away from the is \(\alpha\)- and towards it is \(\beta\)-configuration, as illustrated in the figure on the right with the help of D-glucose example.

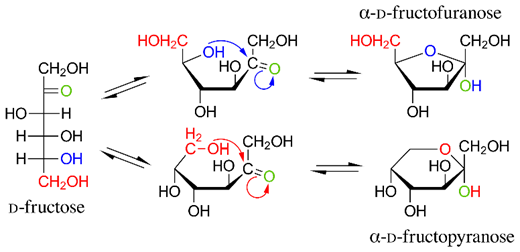

D-Fructose exists in five-membered and six-membered hemiacetal forms, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\).

Furanose is a five-membered, and pyranose is a six-membered cyclic hemiacetal of monosaccharide. These names originate from the names of cyclic ethers, furan, and pyran, shown in the figure on the right. Based on this nomenclature, the class name of \(\alpha\)-D-Glucose is \(\alpha\)-D-glucopyranose and of \(\beta\)-D-glucose is \(\beta\)-D-glucopyranose. D-Fructose exists in pyranose and furanose forms, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\).

Furanose is a five-membered, and pyranose is a six-membered cyclic hemiacetal of monosaccharide. These names originate from the names of cyclic ethers, furan, and pyran, shown in the figure on the right. Based on this nomenclature, the class name of \(\alpha\)-D-Glucose is \(\alpha\)-D-glucopyranose and of \(\beta\)-D-glucose is \(\beta\)-D-glucopyranose. D-Fructose exists in pyranose and furanose forms, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\).

Chair conformations of pyranose forms

Haworth projections assume a flat ring structure. It is close to the structure of furanose forms (five-membered rings), but pyranose forms (six-membered rings) exist in chair conformations. The figure on the right shows a chair conformation of a six-membered cyclic structure. The points to note are the following.

Haworth projections assume a flat ring structure. It is close to the structure of furanose forms (five-membered rings), but pyranose forms (six-membered rings) exist in chair conformations. The figure on the right shows a chair conformation of a six-membered cyclic structure. The points to note are the following.

- Each \(\ce{C}\) has two bonds (shown in black) in the cycle, one axial bond (shown in red) pointing along the axis of the cycle and one equatorial bond (shown in blue) pointing approximately along the equator of the cycle.

- The axial bonds point in opposite directions, up and down, on neighboring \(\ce{C'}\). The same applies to equatorial bonds.

- Bulky group, i.e., any group other than \(\ce{-H}\), is more stable at the equatorial than axial position because of steric strain (push away) from the other two axial positions on the same face of the ring., as illustrated in the figure on the left.

How to draw chair conformations of monosaccharides

Alpha (\(\alpha\)) and axial start with the letter a. Remember \(\ce{C}\)

Since \(\alpha\)\(\ce{-OH}\) is axial, \(\beta\)\(\ce{-OH}\) is equatorial at anomeric \(\ce{C}\). The Howarth projection of \(\beta\)-D-glucose in the figure on the right shows that the bulky groups alternate between up and down positions on \(\ce{C}\)#1 to \(\ce{C}\)#5. It means all of them are either axial or equatorial. Since \(\beta\)\(\ce{-OH}\) is equatorial, all bulky groups in \(\beta\)-D-glucose are equatorial, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\).

After learning how to draw \(\beta\)-D-glucopyranose, the other monosaccharides can be drawn easily based on the knowledge of the difference from \(\beta\)-D-glucopyranose. For example, \(\beta\)-D-manopyranose is \(\ce{C}\)#2 epimer, \(\beta\)-D-galactopyranose is \(\ce{C}\)#4 epimer, and their \(\alpha\) forms have an axial \(\ce{-OH}\) at anomeric \(\ce{C}\), as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\).

Mutarotation

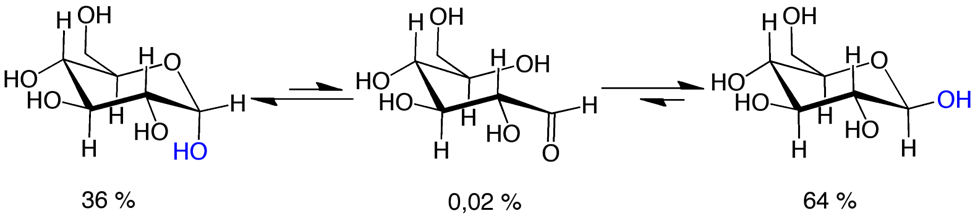

D-Glucose is a chiral compound. A freshly prepared aqueous solution of \(\beta\)-D-glucopyranose has a specific rotation of +112.2. A freshly prepared solution of \(\alpha\)-D-glucopyranose has a specific rotation of +18.7. However, the specific rotation of \(\beta\)-D-glucopyranose and \(\alpha\)-D-glucopyranose gradually changes to +52.5. This is because the open chain and the two cyclic forms establish equilibrium in the solution, as illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\).

Open chain and the two cyclic forms of D-glucose exist in equilibrium in solution where \(\beta\)-D-glucose has all bulky group in equatorial position is the most stable, \(\alpha\)-D-glucose with one bulky group in axial position is the second most stable and, and open chain for is the least stable, as reflected by their proportions at equilibrium shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\).

Mutarotation is the change in the optical rotation of carbohydrate solution over time due to the change in the composition of different compound forms to achieve equilibrium composition.

Anomeric

Anomeric