4.8: Electrophilic aromatic substitution reactions

- Page ID

- 416450

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Understand the difference in the electrophilicity of \(\pi\)-bond of benzene and alkenes.

- Draw the electrophilic aromatic substitution mechanism with curly arrows showing the flow of electrons.

- Apply the electrophilic aromatic substitution to some reactions of benzene, including halogenation, nitration, sulfonation, alkylation, and acylation reactions.

Which electrophiles can react with an aromatic substrate?

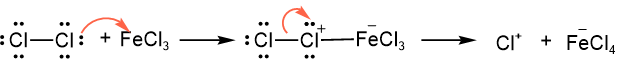

The \(\pi\)-bonds in a benzene ring of aromatic compounds are weaker nucleophiles than the \(\pi\)-bonds in alkenes. This is because breaking a \(\pi\)-bond of alkene costs about 260 kJ/mole energy, but breaking a \(\pi\)-bond in an aromatic substrate costs an additional 208 kJ/mol because the aromatic stabilization is lost. Unlike alkenes, the aromatic substrates do not react with partial positive (\(\ce{\overset{\delta{+}}{A}{-}\overset{\delta{-}}{B}}\)) electrophiles. The aromatic substrates react with electrophiles in their most reactive cation \(\ce{E^{+}}\) form. The cation electrophiles are generated in situ by acid-base or Lewis acid-Lewis base reactions. For example, halogens (\(\ce{X-X}\) react as Lewis bases with Lewis acids like \(\ce{AlX3}\) or \(\ce{FeX3}\), where \(\ce{X}\) is a halogen atom (\(\ce{Cl}\) or \(\ce{Br}\)). The Lewis acid receives a lone pair from one halogen atom causing a heterolytic breaking of \(\ce{X-X}\). The other halogen leaves as \(\ce{X^{+}}\), as shown below.

Similar reaction happens when an alkylhalide (\(\ce{R-X}\) or an acyl halide ( \(\ce{R-\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace\!{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{C}}\!\!-X}\)) reacts with Lewis acid, as shown below.

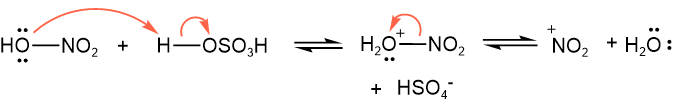

An \(\ce{-OH}\) bonded with a potential electrophile \(\ce{E^{+}}\) can be converted into a better leaving \(\ce{-\overset{+}{O}H2}\) group by adding a stronger acid to the substrate. The \(\ce{-{\overset{+}{O}}H2}\) leaves as neutral neucleophile \(\ce{H2O}\), leaving behind the \(\ce{E^{+}}\). For example, protonation of nitric acid with sulfuric acid generated nitronium ion (\(\ce{\overset{+}{N}O2}\)), as shown below.

Like the auto-ionization of water, the autoionization of sulfuric acid followed by elimination of \(\ce{H2O}\) generates protonated sulfur trioide (\(\ce{\overset{+}{S}O3H}\)), as shown below.

Electrophilic aromatic substitution mechanism

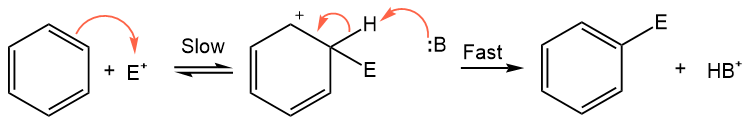

The nucleophilic \(\pi\)-bond of an aromatic compound attacks the cation electrophile (\(\ce{E^{+}}\)), as shown in step#1 in the mechanism illustrated below. Any base group in the medium removes the acidic proton that re-establishes the \(\pi\)-bond in Step#2.

Removal of the proton by a base is preferred over electrophile attacking the carbonation intermediate in step#2, because aromatic stabilization decreases the energy barrier for the former. It is called electrophilic aromatic substitution reaction because an electrophile \(\ce{E^{+}}\) substitutes another electrophile \(\ce{H^{+}}\) from an aromatic substrate.

Examples of electrophilic aromatic substitution reactions

Some fo the important electrophilic aromatic substitution reactions of benzene are listed below.

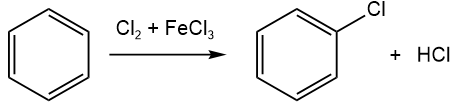

- Halogenation of benzene substitutes a \(\ce{-H}\) with a halogen (\(\ce{-Cl}\) or \(\ce{-Br}\)), as shown below.

- Nitration of benzene substitutes a \(\ce{-H}\) with nitro group (\(\ce{-NO2}\)) by the following reaction.

- Sulfonation of benzene substitutes a \(\ce{-H}\) with sulfonic acid group (\(\ce{-SO3H}\)) by the following reaction.

- Alkylation of benzene substitutes a \(\ce{-H}\) with alkyl acid group (\(\ce{-R}\)), e.g.,:

- Acylation of benzene substitutes a \(\ce{-H}\) with acyl group (\(\ce{-\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace\!{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{C}}\!\!-R}\)), e.g.,: