2.5: Functional groups containing mix of sp3- and sp2-, or sp-hybridized heteroatom

- Page ID

- 407588

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Identify, assign IUPAC name, and draw structure from the IUPAC name of carboxylic acids and their derivatives, including acid halides, acid anhydrides, esters, amides, and nitriles.

- Predict the changes in the polarity and its effect on the reactivity of carboxylic acids and their derivatives, including acid halides, acid anhydrides, esters, amides, and nitriles.

- Identify phosphoric acid, anhydrides of phosphoric acids, phosphate anions, and esters of phosphoric acids.

What are carboxylic acids and carboxylic acid derivatives?

Carboxylic acids have a carbonyl group (\(\ce{C=O}\)) and a hydroxyl group (\(\ce{-OH}\)) on the same carbon, i.e., \(\ce{-\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace\!{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{C}}\!\!-OH}\) group. The carboxylic acid group is represented as \(\ce{-\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace\!{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{C}}\!\!-OH}\), or as \(\ce{-COOH}\). Carboxyl acids have some characteristics of the \(\ce{C=O}\) group, some characteristics of the \(\ce{-OH}\) group, and some additional characteristics due to the interaction of the two groups. In carboxylic acid derivates, the \(\ce{-OH}\) group is replaced with another group, that includes acid halides (\(\ce{R-\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace\!{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{C}}\!\!-X}\)), acid anhydrides (\(\ce{R-\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace\!{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{C}}\!\!-O-\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace\!{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{C}-R'}}\)), easters (\(\ce{R-\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace\!{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{C}}\!\!-OR'}\)), and amides (\(\ce{R-\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace\!{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{C}}\!\!-NH2}\)). Nitrile group that has the carbonyl \(\ce{O}\) replaced with a \(\ce{N}\) and the \(\ce{-OH}\) group also replaced with the same \(\ce{N}\), i.e., \(\ce{R-C≡N}\) group is also classified as a carboxylic acid derivative. The nomenclature and physical characteristics of carboxylic acids and their derivatives are described in the following sections.

Carboxylic acids (\(\ce{R-\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace\!{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{C}}\!\!-OH}\))

Nomenclature of carboxylic acids

The IUPAC nomenclature of the carboxylic acids follows the following rules.

- The longest hydrocarbon chain containing the carboxylic acid group is chosen as the parent name, with the last letter 'e' of its suffix replaced with -oic acid. For example, \(\ce{HCOOH}\) is methanoic acid, \(\ce{CH3COOH}\) is ethanoic acid, and \(\ce{CH3CH2COOH}\) is propanoic acid.

- If there are two carboxylic acid groups, the suffix changes to -dioic acid, e.g., \(\ce{HOOC-COOH}\) is ethanedioc acid, and \(\ce{HOOC-CH2-COOH}\) is propanedioic acid. (note that when the suffix begins with a consonant (the letter 'd' in this case), the last letter 'e' of the parent hydrocarbon name is not dropped)

- Start numbering from the \(\ce{C}\) of the \(\ce{-COOH}\) group. The \(\ce{-COOH}\) group itself does not need a location number, as it is always at the end of the chain.

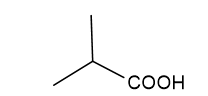

2-methylpropanoic acid

2-methylpropanoic acid prop-2-enoic acid

prop-2-enoic acid- If the \(\ce{-COOH}\) group is bonded to a cyclic chain, the suffix -carboxylic acid is added to the name of the cyclic hydrocarbon. Numbering starts from the point of attachment of \(\ce{-COOH}\) to the ring.

cyclohexanecarboxylic acid

cyclohexanecarboxylic acid cyclohex-2-ene-1-carboxylic acid

cyclohex-2-ene-1-carboxylic acid- If the \(\ce{-COOH}\) group is bonded to a benzene ring, the parent name "benzoic acid is used.

- Numbering starts from the point of attachment of the \(\ce{-COOH}\) group to the ring.

benzoic acid

benzoic acid 2-hydroxybenzoic acid

2-hydroxybenzoic acid What is the IUPAC name of the compound shown on the right?

What is the IUPAC name of the compound shown on the right?

Solution

- The longest chain counting the \(\ce{-COOH}\) group is three \(\ce{C's}\) and a double bond, so the parent name is propene and replace the last letter 'e' with -oic acid, i.e., propenoic acid.

- There is a methyl group attached that becomes a prefix, i.e., methylpropenoic acid.

- A location number is needed for the methyl group and the double bond. Start numbering from the \(\ce{C}\) of the \(\ce{-COOH}\) group, double bond receives#2 and the methyl group receives #2.

Answer: 2-methylprop-2-enoic acid

The common name of 2-methylprop-2-enoic acid is methacrylic acid, and prop-2-enoic acid is acrylic acid, the monomers (the repeating units) in some polymers.

What is the IUPAC name of the compound shown on the right?

What is the IUPAC name of the compound shown on the right?

Solution

The \(\ce{-COOH}\) group is attached to a five \(\ce{C}\) cyclic chain, so the name of the cyclic chain becomes the parent name: cyclopentane.

Add the suffix -carboxylic acid to the parent name to indicate the carboxylic acid group attached to a cyclic chain.

Answer: cyclopentanecarboxylic acid

What is the IUPAC name of the compound shown on the right?

What is the IUPAC name of the compound shown on the right?

Solution

- A carboxylic acid bonded to a benzene ring takes "benzoic acid" as the parent name.

- A \(\ce{-OH}\) group takes the prefix "hydroxy" in the presence of a \(\ce{-COOH}\) group, i.e., hydroxybenzoic acid.

- Start numbering from the point of attachment of the \(\ce{-COOH}\) group: the \(\ce{-OH}\) group receives #4.

Answer: 4-hydroxybenzoic acid.

Common names of carboxylic acids

Common names of carboxylic acids are derived from the names of natural sources of these acids. Table 1 lists some of the common names of carboxylic acids.

| Condensed formula | IUPACE name | Common name | Source of the common name |

|---|---|---|---|

| \(\ce{HCOOH}\) | methanoic acid | formic acid | Latin: formica, ant |

| \(\ce{CH3COOH}\) | ethanoic acid | acetic acid | Latin: acetum, vinegar |

| \(\ce{CH3CH2COOH}\) | propanoic acid | propionic acid | Greek: propion, first fat |

| (\ce{CH3(CH2)2COOH}\) | butanoic acid | butyric acid | Latin: butyrum, butter |

| (\ce{CH3(CH2)4COOH}\) | hexanoic acid | caproic acid | Latin: caper, goat |

| (\ce{CH3(CH2)14COOH}\) | hexadecanoic acid | palmitic acid | Latin: palma, palm tree |

| (\ce{CH3(CH2)16COOH}\) | octadecanoic acid | stearic acid | Greek: stear, solid fat |

| (\ce{CH3(CH2)18COOH}\) | eicosanoic acid | arachidic acid | Greek: arachis, peanut |

The first syllable of the common names, e.g., form-, acet-, prop-, etc., are also used as the first syllable of the common names of related compounds. For example, \(\ce{HCOH}\) is formaldehyde, \(\ce{CH3COH}\) is acetaldehyde, etc.

Physical properties of carboxylic acids

The carboxylic acid group has a \(\ce{C=O}\) and a \(\ce{-OH}\) groups, i.e., an sp2- and an sp3 hybridized \(\ce{O}\) bonded to the same \(\ce{C}\). Both \(\ce{O's}\) have two lone pairs of electrons on them, i.e., \(\ce{-\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace\!{:O:}}|\!\!\!\!|\enspace}{C}}\!\!-\overset{\Large{\cdot\cdot}}{\underset{\Large{\cdot\cdot}}{O}}-H}\). Lone pair of electrons are usually not shown except when needed, i.e., the carboxylic acid group is represented as \(\ce{-\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace\!{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{C}}\!\!-OH}\) or as \(\ce{-COOH}\).

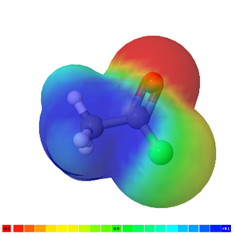

The carboxylic acid group has three polar bonds, i.e., \(\ce{\overset{\delta{+}}{C}{=}\overset{\delta{-}}{O}}\), \(\ce{\overset{\delta{+}}{C}{-}\overset{\delta{-}}{O}}\) and \(\ce{\overset{\delta{-}}{O}{-}\overset{\delta{+}}{H}}\), resulting in a polar group: \(\ce{-\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace\!{\overset{\Large{\delta{-}}}{O}}}|\!\!|\enspace}{\overset{\delta{+}}{C}}}\!\!-\overset{\delta{-}}{O}-\overset{\delta{+}}{H}}\). This is because \(\ce{O}\) are more electronegative than \(\ce{C}\) (3.3-2.6 = 0.7) and \(\ce{H}\) (3.3-2.2 = 1.17), as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\). It makes \(\ce\overset{\delta{+}}{C}\) an electrophile, \(\ce\overset{\delta{-}}{O}\) a nucleophile or a base, and \(\ce\overset{\delta{+}}{H}\) an acid in reactivity. Due to the acid protons, carboxylic acids are also classified as organic acids.

The polar \(\ce{\overset{\delta{+}}{C}{=}\overset{\delta{-}}{O}}\) and \(\ce{\overset{\delta{-}}{O}{-}\overset{\delta{+}}{H}}\) bonds allow dipole-dipole interactions and hydrogen bonding in addition to the London dispersion forces. Carboxylic acids have stronger intermolecular forces, higher melting points, higher boiling points, and higher solubilities in water compared to alcohols and aldehydes of comparable molar mass due to more intermolecular forces, as compared in Table 2.

| Condensed formula | IUPAC name | Molar mass (g/mol) | Boiling point (oC) | Solubility in water |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| \(\ce{CH3(CH2)2COOH}\) | Butanoic acid | 88.1 | 163 | Miscible |

| \(\ce{CH3(CH2)3CH2OH}\) | Pentan-1-ol | 88.1 | 137 | 2.3 g/100 mL |

| \(\ce{CH3(CH2)3CHO}\) | Pentanal | 86.1 | 103 | Slightly soluble |

Two carboxylic acids can make two hydrogen bonds with each other, as illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\), behaving as a dimer with two times higher molecular mass. It explains their higher boiling points than alcohols of the same molar mass. Carboxylic acids of up to five \(\ce{C's}\), i.e., methanoic acid, ethanoic acid, propanoic acid, butanoic acid, and pentanoic acid, are soluble in water. Hexanoic acid is slightly soluble, and higher acids are insoluble.

Carboxylic acids have a sour taste because they are acids due to ionizable proton in their \(\ce{-O-H}\) groups. For example, the sour taste of citrus fruits is due to citric acid, and the sour taste of vinegar is due to ethanoic acid.

Oxidation is i) loss of electrons, ii) gain of \(\ce{O}\), or loss of \(\ce{H}\); and the reduction is the opposite of these. Oxidation and reduction happen together and are collectively called Redox reactions. Most chemical reactions in biological systems are redox reactions, e.g., photosynthesis is a reduction of \(\ce{CO2}\) to convert solar energy into potential chemical energy, and digestion of food is the opposite, i.e., oxidation to release the energy for the activities of life.

A major portion of organic compounds is hydrocarbon groups, gradually oxidized to alcohols, aldehydes or ketones, carboxylic acids, and finally, carbon dioxide and water, releasing energy. For example, methane (\(\ce{CH4}\)) oxidizes to methanol (\(\ce{CH3OH}\)), methanal (\(\ce{CH2O}\)), methanoic acid (\(\ce{HCOOH}\)), and finally to carbon dioxide (\(\ce{CO2}\)) that is exhaled, as shown below.

The alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, and carboxylic acids also serve as intermediates for synthesizing compounds the body needs. Carboxylic acids commonly appear in the metabolic process. For example, glucose, a six \(\ce{C}\) compound, is first converted to two pyruvic acid molecules. Under low oxygen conditions (anaerobic), pyruvic acid is reduced to lactic acid.

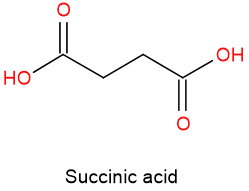

In the presence of oxygen (aerobic), pyruvic acid releases a \(\ce{CO2}\) and becomes a two \(\ce{C}\) group that joins a four \(\ce{C}\) compound oxalic acid to make a six \(\ce{C}\) compound citric acid. Citric acid releases a \(\ce{CO2}\) and becomes a five \(\ce{C}\) compound \(\alpha\)-ketoglutaric acid, which releases another \(\ce{CO2}\) and becomes four \(\ce{C}\) compound succinic acid, as shown below. This process goes on through several intermediate carboxylic acids, and either all the \(\ce{C's}\) of the starting compound convert to \(\ce{CO2}\), or the intermediate is utilized to synthesize compounds needed by the body.

,

,  , and

, and

Note: The carboxylic acids are shown as neutral acids in the above example, but in the physiological conditions, they exist as anions, i.e., as a carboxylate group (\(\ce{-\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace\!{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{C}}\!\!-O^{-}}\)). These points will be discussed in a later chapter.

Acid halides and acid anhydrides -the most reactive acid derivatives

Nomenclature of acid halides

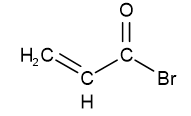

Acid halides contain the (\(\ce{-\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace\!{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{C}}\!\!-X}\)) group, where \(\ce{X}\) can be \(\ce{F}\), \(\ce{Cl}\), \(\ce{Br}\), or \(\ce{I}\).

- IUPAC name of the acid halide takes the name of the corresponding carboxylic acid with the suffix -oic acid replaced with -oil halide, as shown in the following examples.

ethanoyl chloride or acetyl chloride

ethanoyl chloride or acetyl chloride propanoyl bromide

propanoyl bromide prop-2-enoyl bromide

prop-2-enoyl bromideAcid chlorides and acid bromides are the most common.

Nomenclature of acid anhydrides

Acid anhydride contains two acyl \(\ce{R-\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace\!{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{C}}\!\!-}\) groups bonded to a common \(\ce{O}\) atom, i.e., (\(\ce{-\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace\!{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{C}}\!\!-O-\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace\!{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{C}-}}\)) group. A carboxylic acid anhydride is derived by condensing two carboxylic acids by losing a \(\ce{H2O}\) molecule. The acid anhydride is symmetric anhydride if both the acids are the same and mixed or asymmetric anhydride if two different acids are condensed to form the anhydride,

- Symmetric acid anhydrides are named using the name of the corresponding acid with the last word 'acid' replaced with 'anhydride', as shown in the following examples.

ethanoic anhydride or acetic anhydride

ethanoic anhydride or acetic anhydride benzoic anhydride

benzoic anhydride- Mixed or asymmetric anhydrides are named by listing the names of the two acids in alphabetic order without the last word 'acid', followed by the word 'anhydride', as shown in the following examples.

ethanoic propanoic anhydride

ethanoic propanoic anhydride accetic benzoic anhydride

accetic benzoic anhydridePhysical properties of acid halides and acid anhydrides

The acid halides group has two polar bonds, i.e., \(\ce{\overset{\delta{+}}{C}{=}\overset{\delta{-}}{O}}\), and \(\ce{\overset{\delta{+}}{C}{-}\overset{\delta{-}}{X}}\) resulting in a polar group: \(\ce{-\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace\!{\overset{\Large{\delta{-}}}{O}}}|\!\!|\enspace}{\overset{\delta{+}}{C}}}\!\!-\overset{\delta{-}}{X}}\). The acid anhydrides have four polar bonds i.e., two \(\ce{\overset{\delta{+}}{C}{=}\overset{\delta{-}}{O}}\), and two \(\ce{\overset{\delta{+}}{C}{-}\overset{\delta{-}}{O}}\) resulting in a polar group: \(\ce{-\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace\!{\overset{\Large{\delta{-}}}{O}}}|\!\!|\enspace}{\overset{\delta{+}}{C}}}\!\!-\overset{\delta{-}}{O}-\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace\!{\overset{\Large{\delta{-}}}{O}}}|\!\!|\enspace}{\overset{\delta{+}}{C}}}-}\). This polarity of the group can be observed in the electrostatic potential maps of acid halide, acid anhydride, and an acid shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)

It is apparent from the comparison of the electrostatic potential maps shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) that the carbonyl \(\ce{C}\) is more bluish, i.e., higher \(\delta{+}\) and stronger nucleophile, in the case of acid halide and acid anhydride than in carboxylic acid. The question is \(\ce{Cl}\) in the acid halide is less electronegative than \(\ce{O}\) in carboxylic acid, then why is the carbonyl \(\ce{C}\) more \(\delta{+}\) in the acid halide than in the acid? The answer is in the fact that the heteroatom not only draws the bonding electron away from the carbonyl \(\ce{C}\), it also donates its lone pair through resonance that diminishes the \(\delta{+}\) character on the carbonyl \(\ce{C}\):

- The 2p-orbital of \(\ce{O}\) and 2p-orbital of \(\ce{C}\) of carboxylic acid are of similar size and overlap well for the reasonce to happen and diminish its \(\delta{+}\) character.

- The 3p-orbital of \(\ce{Cl}\) or 4p orbital of \(\ce{Br}\) overlaps poorly with 2p-orbital of carbonyl \(\ce{C}\) due to the size difference and does not diminish its \(\delta{+}\) character.

- The (\ce{O}\) is shared between to \(\ce{C=O}\) groups in the case of acid anhydride. So it diminish \(\delta{+}\) character of \(\ce{C=O}\) less than in carboxylic acids.

Due to the highly nucleophilic carbonyl \(\ce{C}\), the acid halides and acid anhydrides are very reactive and primarily used as reactive intermediates in chemical synthesis. Again due to their high reactivity, they can not survive in biological systems. Biochemical systems use carboxylic acid derivatives containing \(\ce{S}\) or phosphate groups as reactive intermediates, which will be described later.

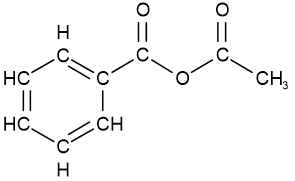

Easters

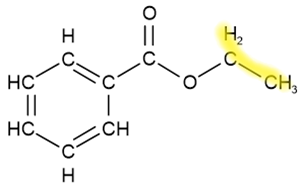

Esters have an acyl group ((\(\ce{R-\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace\!{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{C}}\!\!-}\)) bonded with an alkoxy group (easters (\(\ce{-OR'}\)), i.e., an easter (\(\ce{R-\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace\!{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{C}}\!\!-OR'}\)) group.

Nomenclature of esters

- IUPAC name of an ester starts with the name of the alkyl group that is part of the alkoxy (\(\ce{-OR'}\)) group, followed by the name of the acid corresponding to the acyl ((\(\ce{R-\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace\!{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{C}}\!\!-}\)) group with the suffix -oic acid replaced with the suffix -oate, as shown in the following examples.

methyl propanoate

methyl propanoate ethyl benzoate

ethyl benzoate propyl acetate

propyl acetate What is the IUPAC name of the compound shown on the right?

What is the IUPAC name of the compound shown on the right?

Solution

- Alkyl group in the alkoxy (\(\ce{-OR'}\)) group is four (\(\ce{C's}\)) i.e., butyl.

- The acyl group is three (\(\ce{C's}\)), i.e., propanoic acid; replace acid with -oate, i.e., propanoate.

Answer: butyl propanoate

What is the IUPAC of the compound shown on the right?

What is the IUPAC of the compound shown on the right?

Solution

- It is an easter where the alkyl group in the alkoxy (\(\ce{-OR'}\)) group is one (\(\ce{C's}\)), i.e., methyl.

- The acyl group contains benzene, i.e., benzoic acid, and replace the -ic acid with -oate, i.e., benzoate.

Answer: methyl benzoate

Physical properties of esters

Esters group has a polar bonds, i.e., \(\ce{\overset{\delta{+}}{C}{=}\overset{\delta{-}}{O}}\), and two polar \(\ce{\overset{\delta{+}}{C}{-}\overset{\delta{-}}{O}}\) groups, resulting in a polar group: \(\ce{-\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace\!{\overset{\Large{\delta{-}}}{O}}}|\!\!|\enspace}{\overset{\delta{+}}{C}}}\!\!-\overset{\delta{-}}{O-R'}}\), as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\). The reactivity of an ester's carbonyl \(\ce{C}\) is almost the same as that of a carboxylic acid.

Easters are pretty common in nature. Small esters are volatile and soluble in water, making them easier to smell and taste. The fragrances of many perfumes and flavors of several fruits are due to esters, as shown in Table 3.

pentyl acetate pentyl acetate |

pentyl methanoate pentyl methanoate |

ethyl heptanoate ethyl heptanoate |

propyl acetate propyl acetate |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Banana |

Plum |

Grape |

Pear |

octyl acetate octyl acetate |

ethyl butanoate ethyl butanoate |

pentyl butanoate pentyl butanoate |

propyl pentanoate propyl pentanoate |

|

Orange |

Pineapple |

Apricot |

Apple |

Fats are esters of carboxylic acids that contain a long chain hydrocarbon, an alkane or alkene with cis double bonds, called fatty acids, and propane-1,2,3-triol also called glycerol, as shown in one example in Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\).

Aspirin is an ester of salicylic acid found in a willow tree's bark. Salicylic acid reduces pain and fever, but it irritates the stomach lining. Aspirin, an ester of salicylic acid, overcomes this problem and is commonly used to reduce pain and fever and as an anti-inflammatory agent. Methyl salicylate is another ester of salicylic acid found in wintergreen oil and used as skin ointments to soothe sore muscles.

|

|

|

| Salicylic acid | Aspirin | Methyl salicylate |

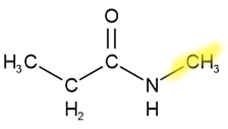

Amides

Amidess have an acyl group ((\(\ce{R-\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace\!{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{C}}\!\!-}\)) bonded with a nitrogen group (\(\ce{-NRR'}\)), i.e., an amide (\(\ce{-\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace\!{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{C}}\!\!-NRR'}\)) group, where \(\ce{R}\) and \(\ce{R'}\) may be \(\ce{H}\) or a hydrocarbon group.

Nomenclature of amides

- IUPAC name of an amide is the name of the acid corresponding to the acyl ((\(\ce{R-\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace\!{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{C}}\!\!-}\)) group with the suffix -oic acid replaced with the word amide.

- If a hydrocarbon group is bonded to nitrogen, its name appears as a prefix preceded by N-.

- If two identical hydrocarbon groups are bonded to nitrogen, the group name is preceded by N, N-di.

- If two different hydrocarbon groups are bonded to nitrogen, the group names, each preceded by N-, are listed alphabetically as prefixes. Some examples are shown below.

ethanamide or acetamide

ethanamide or acetamide N-methylpropanamide

N-methylpropanamide N,N-dimethylmethanamide or N,N-dimethylformaide

N,N-dimethylmethanamide or N,N-dimethylformaide N-ethyl-N-methylpropanamide

N-ethyl-N-methylpropanamide- An amide group attached to a benzene ring takes the base name 'benzamide,' as shown in the following examples.

benzamide

benzamide 3-methylbenzamide

3-methylbenzamide What is the IUPAC name of the compound shown on the right?

What is the IUPAC name of the compound shown on the right?

Solution

- There is an amide group on a four \(\ce{C}\) chain, i.e., butanoic acid, which changes to butanamide.

- There is a methyl group on nitrogen that becomes the prefix N-methyl.

Answer: N-methylbutanamide

What is the IUPAC name of the compound shown on the right?

What is the IUPAC name of the compound shown on the right?

Solution

- There are two amide groups, so it takes the suffix -diamide.

- The corresponding acid is a six \(\ce{C}\) diacid named hexanedioic acid. Replace -oic acid with amide.

Answer: hexanediamid

Physical properties of amides

Amide group has a polar bonds, i.e., \(\ce{\overset{\delta{+}}{C}{=}\overset{\delta{-}}{O}}\), \(\ce{\overset{\delta{+}}{C}{-}\overset{\delta{-}}{N}}\), and \(\ce{\overset{\delta{-}}{N}{-}\overset{\delta{+}}{H}}\) groups, resulting in a polar group: \(\ce{-\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace\!{\overset{\Large{\delta{-}}}{O}}}|\!\!|\enspace}{\overset{\delta{+}}{C}}}\!\!-\overset{\delta{-}}{N}-R'R"}\), as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\).

Comparison of electrostatic potential maps in Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\) shows that the carbonyl \(\ce{C}\) of amide is less \(\delta{+}\), i.e., less electrophilic than that of the corresponding carboxylic acid. This is because of two reasons i) \(\ce{N}\) is less electronegative and draws electrons away less than \(\ce{O}\) and ii) being less electronegative, \(\ce{N}\) sends its lone pair of electrons more to the carbonyl \(\ce{C}\) neutralizing its \(\delta{+}\) by resonance than \(\ce{O}\). Both of these factors make the carbonyl \(\ce{C}\) less \(\delta{+}\) and less electrophilic, which makes amides one of the lest reactive and the most stable carboxylic acid derivatives that are found commonly in nature. The resonance effect is illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\) below. Due to the resonance, the \(\ce{C-N}\) bond has a significant double bond character.

Since the lone pair of electrons of amide are occupied in the resonance, they are less available to protons of acids. Therefore, amides are much less basic than amines. Amides have \(\ce{\overset{\delta{-}}{N}{-}\overset{\delta{+}}{H}}\) bonds that allow them to make hydrogen bonds with water molecules. Therefore, amides containing up to five \(\ce{C's}\) are soluble in water due the hydrogen bonding. Those with larger alkyl groups, i.e., with more than five \(\ce{C's}\) are slightly soluble or insoluble due to the hydrophobic character of the alkyl groups dominating over the hydrophilic nature of the amide group.

Amides in nature and medicines

Proteins are made of small repeat units, called amino acids, joined through amide groups, as illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\), which makes amide one of the most common groups present in nature.

During the digestion of proteins, \(\ce{N's}\) end up in urea excreted by kidneys. If kidneys malfunction, urea may build to a toxic level, resulting in uremia. Urea is also used as a fertilizer.

Barbiturates derived from barbituric acid have sedative and hypnotic effects and are used in medicines for these effects. Barbiturate drugs include phenobarbital and pentobarbital. Phenacetin and acetaminophen are amides used in Tylenol as alternatives to reduce fever and pain but with little anti-inflammatory effect. The structures of these amides are shown below.

|

urea |

barbituric acid |

phenobarbital phenobarbital |

pentobarbital pentobarbital |

phenacetin phenacetin |

acetaminophen acetaminophen |

cyclic amides are called lactams. A four-member lactam is a common feature in the structure of Penicillin and related synthetic antibiotics, as shown below.

|

|

|

|

| A four-membered lactam |

Penicillin G | Amoxicillin | Cephalexin |

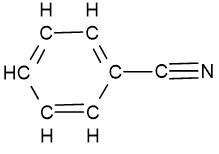

Nitriles

Nitriles have cyano group that is a polar bond \(\ce{-\overset{\delta{+}}{C}{≡}\overset{\delta{-}}{N}\!:}\) with a lone pair in one of the sp orbital of \(\ce{N}\), as illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\).

IUPAC name of nitriles is composed of the name of the hydrocarbon skeleton, including the \(\ce{C}\) in the nitrile group with the suffix -nitrile.

Another way of naming them is to take the name of the corresponding carboxylic acid but replace the suffix -oic acid with -onitrile, as shown in the following example.

acetonitrile or ethannitrile

acetonitrile or ethannitrile propanenitrile

propanenitrile benzonitrile

benzonitrileNitriles are not very common in nature but are important as intermediates in synthesizing organic compounds.

Phosphorous groups

Phosphorous (\(\ce{P}\)) is in the same group with \(\ce{N}\) in periodic table. Like \(\ce{N}\) in ammonia (\(\ce{{H}-\overset{\bullet\bullet}{\underset{\underset{\huge{H}} |}{N}}\!-H}\)), the \(\ce{P}\) can have three bonds and a lone pair, as in phosphine (\(\ce{{H}-\overset{\bullet\bullet}{\underset{\underset{\huge{H}} |}{P}}\!-H}\)) with eight valence electrons, i.e., octet complete. Unlike \(\ce{N}\), the \(\ce{P}\) is in fourth row in the periodic table and, like other elements of the fourth and higher row, can have more than eight valence electrons in its compounds, e.g., ten valence electrons in phosphoric acid (\(\ce{HO-\!\!\!\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{\underset{\underset{\huge\enspace\,{OH}} |}{P}}}\!\!\!\!-OH}\)). Phosphorous groups are important in biological systems, e.g., they are part of DNA molecules, phospholipids in cell membranes, and energetic molecules like adenosine triphosphate that are used as energy currency in biochemical reactions.

Phosphoric acid and phosphoric anhydrides

Phosphoric acid or orthphosphosporic acid has three \(\ce{-OH}\) groups and one \(\ce{=O}\) bonded to a \(\ce{P}\) atom, i.e., \(\ce{HO-\!\!\!\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{\underset{\underset{\huge\enspace\,{OH}} |}{P}}}\!\!\!\!-OH}\). Like carboxylic acid anhydride, which is two carboxylic acids joined through a common \(\ce{O}\), two phosphoric acids joined through a common \(\ce{O}\) is a diphosphoric acid or a pyrophosphoric acid, and three phosphoric acids condensed in this way is a triphosphoric acid. Their corresponding anions formed after ionizing the acidic protons from the \(\ce{-OH}\) groups are called phosphates, and alkoxy (\(\ce{-OR}\) replacing one or more \(\ce{-OH}\) groups are phosphate esters, as shown below.

|

\(\ce{HO-\!\!\!\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{\underset{\underset{\huge\enspace\,{OH}} |}{P}}}\!\!\!\!-OH}\) Phosphoric acid or orthphosphosporic acid |

\(\ce{HO-\!\!\!\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{\underset{\underset{\huge\enspace\,{OH}} |}{P}}}\!\!\!\!-O-\!\!\!\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{\underset{\underset{\huge\enspace\,{OH}} |}{P}}}\!\!\!\!-OH}\) diphosphoric acid or a pyrophosphoric acid |

\(\ce{HO-\!\!\!\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{\underset{\underset{\huge\enspace\,{OH}} |}{P}}}\!\!\!\!-O-\!\!\!\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{\underset{\underset{\huge\enspace\,{OH}} |}{P}}}\!\!\!\!-O-\!\!\!\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{\underset{\underset{\huge\enspace\,{OH}} |}{P}}}\!\!\!\!-OH}\) triphosphoric acid |

|

\(\ce{^{-}O-\!\!\!\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{\underset{\underset{\huge\enspace\,{O^{-}}} |}{P}}}\!\!\!\!-O^{-}}\) Phosphate ion or orthphosphate ion |

\(\ce{^{-}O-\!\!\!\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{\underset{\underset{\huge\enspace\,{O^{-}}} |}{P}}}\!\!\!\!-O-\!\!\!\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{\underset{\underset{\huge\enspace\,{O^{-}}} |}{P}}}\!\!\!\!-O^{-}}\) diphosphate ion or a pyrophosphate ion |

\(\ce{^{-}O-\!\!\!\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{\underset{\underset{\huge\enspace\,{O^{-}}} |}{P}}}\!\!\!\!-O-\!\!\!\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{\underset{\underset{\huge\enspace\,{O^{-}}} |}{P}}}\!\!\!\!-O-\!\!\!\!\!{\overset{\overset{\huge\enspace{O}}|\!\!|\enspace}{\underset{\underset{\huge\enspace\,{O^{-}}} |}{P}}}\!\!\!\!-O^{-}}\) triphosphate ion |

Phosphoric esters

Like carboxylic acid changes to an ester when its \(\ce{-OH}\) group is replaced with an alkoxy (\(\ce{-OR}\)) group, phosphoric acid changes to mono phosphoric ester when one of its \(\ce{-OH}\) groups are replaced with alkoxy (\(\ce{-OR}\)), to diester when two \(\ce{-OH}\) groups are replaced with alkoxy (\(\ce{-OR}\)), and to triester when three \(\ce{-OH}\) groups are replaced with alkoxy (\(\ce{-OR}\)).

- The phosphoric esters are named by listing the names of the alkyl parts of the alkoxy groups in alphabetic order, followed by the world phosphate.

- In more complex phosphodiesters, it is common practice to name the organic compound followed by the word 'phosphate' or prefixed phospho-, as shown in the following examples.

|

dimethyl phosphate |

ethyl methyl phosphate |

dihydroxyacetone phosphate |

adenosine triphosphate adenosine triphosphate |