3.5: Naming Monoatomic Ions

- Page ID

- 86601

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Name monoatomic ions using the defined nomenclature rules.

After learning a few more details about the names of individual ions, you will be a step away from knowing how to name ionic compounds. This section begins the formal study of nomenclature, the systematic naming of chemical compounds.

Naming Cations

The name of a monatomic cation is simply the name of the element followed by the word ion. Thus, Na+ is the sodium ion, Al3+ is the aluminum ion, Ca2+ is the calcium ion, and so forth.

We have seen that some elements lose different numbers of electrons, producing ions of different charges. Iron, for example, can form two cations, each of which, when combined with the same anion, makes a different ionic compound with unique physical and chemical properties. Thus, we need a different name for each iron ion to distinguish Fe2+ from Fe3+. The same issue arises for other ions with more than one possible charge.

There are two ways to make this distinction. In the simpler, more modern approach, called the stock system, an ion’s positive charge is indicated by a roman numeral in parentheses after the element name, followed by the word ion. Thus, Fe2+ is called the iron(II) ion, while Fe3+ is called the iron(III) ion. This system is used only for elements that form more than one common positive ion. We do not call the Na+ ion the sodium(I) ion because (I) is unnecessary. Sodium forms only a 1+ ion, so there is no ambiguity about the name sodium ion.

The second system, called the common system, is not conventional but is still prevalent and used in the health sciences. This system recognizes that many metals have two common cations. The common system uses two suffixes (-ic and -ous) that are appended to the stem of the element name. The -ic suffix represents the greater of the two cation charges, and the -ous suffix represents the lower one. In many cases, the stem of the element name comes from the Latin name of the element. Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) lists the elements that use the common system, along with their respective cation names.

| Element | Charge | Symbol | Common System Name | Stock System Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| chromium | 2+ | Cr2+ | chromous ion | chromium(II) ion |

| 3+ | Cr3+ | chromic ion | chromium(III) ion | |

| copper | 1+ | Cu+ | cuprous ion | copper(I) ion |

| 2+ | Cu2+ | cupric ion | copper(II) ion | |

| iron | 2+ | Fe2+ | ferrous ion | iron(II) ion |

| 3+ | Fe3+ | ferric ion | iron(III) ion | |

| lead | 2+ | Pb2+ | plumbous ion | lead(II) ion |

| 4+ | Pb3+ | plumbic ion | lead(IV) ion | |

| tin | 2+ | Sn2+ | stannous ion | tin(II) ion |

| 4+ | Sn4+ | stannic ion | tin(IV) ion |

Naming Anions

The name of a monatomic anion consists of the stem of the element name, the suffix -ide, and then the word ion. Thus, as we have already seen, Cl− is “chlor-” + “-ide ion,” or the chloride ion. Similarly, O2− is the oxide ion, Se2− is the selenide ion, and so forth. Table \(\PageIndex{2}\) lists the names of some common monatomic ions.

| Element | Charge | Symbol | Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| fluorine | 1– | F− | fluoride ion |

| chlorine | 1– | Cl− | chloride ion |

| bromine | 1– | Br− | bromide ion |

| iodine | 1– | I− | iodide ion |

| oxygen | 2– | O2− | oxide ion |

| sulfur | 2– | S2− | sulfide ion |

| phosphorous | 3– | P3− | phosphide ion |

| nitrogen | 3– | N3− | nitride ion |

Name each ion.

- Ca2+

- S2−

- SO32−

- NH4+

- Cu+

- Answer a

-

the calcium ion

- Answer b

-

the sulfide ion (from Table \(\PageIndex{2}\) )

- Answer c

-

the sulfite ion

- Answer d

-

the ammonium ion

- Answer e

-

the copper(I) ion or the cuprous ion (copper can form cations with either a 1+ or 2+ charge, so we have to specify which charge this ion has

Name each ion.

- Fe2+

- Fe3+

- SO42−

- Ba2+

- HCO3−

- Answer a

-

the iron (II) or ferrous ion

- Answer b

-

the iron (III) or ferric ion

- Answer c

-

the sulfate ion

- Answer d

-

the barium ion

- Answer e

-

the bicarbonate ion or hydrogen carbonate ion

Write the formula for each ion.

- the bromide ion

- the phosphate ion

- the cupric ion

- the magnesium ion

- Answer a

-

Br−

- Answer b

-

PO43−

- Answer c

-

Cu2+

- Answer d

-

Mg2+

Write the formula for each ion.

- the fluoride ion

- the carbonate ion

- the ferrous ion

- the potassium ion

- Answer a

-

F−

- Answer b

-

CO32-

- Answer c

-

Fe2+

- Answer d

-

K+

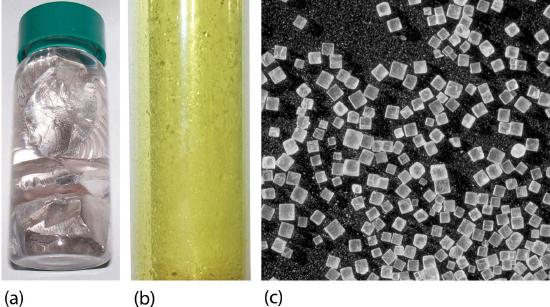

The element sodium (part [a] in the accompanying figure) is a very reactive metal; given the opportunity, it will react with the sweat on your hands and form sodium hydroxide, which is a very corrosive substance. The element chlorine (part [b] in the accompanying figure) is a pale yellow, corrosive gas that should not be inhaled due to its poisonous nature. Bring these two hazardous substances together, however, and they react to make the ionic compound sodium chloride (part [c] in the accompanying figure), known simply as salt.

Salt is necessary for life. Na+ ions are one of the main ions in the human body and are necessary to regulate the fluid balance in the body. Cl− ions are necessary for proper nerve function and respiration. Both of these ions are supplied by salt. The taste of salt is one of the fundamental tastes; salt is probably the most ancient flavoring known, and one of the few rocks we eat.

The health effects of too much salt are still under debate, although a 2010 report by the US Department of Agriculture concluded that "excessive sodium intake…raises blood pressure, a well-accepted and extraordinarily common risk factor for stroke, coronary heart disease, and kidney disease."US Department of Agriculture Committee for Nutrition Policy and Promotion, Report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, accessed January 5, 2010. It is clear that most people ingest more salt than their bodies need, and most nutritionists recommend curbing salt intake. Curiously, people who suffer from low salt (called hyponatria) do so not because they ingest too little salt but because they drink too much water. Endurance athletes and others involved in extended strenuous exercise need to watch their water intake so their body's salt content is not diluted to dangerous levels.