1.9: Band Theory in Solids

- Page ID

- 221677

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The LCAO method for cyclic systems provides a convenient starting point for the development of the electronic structure of solids.

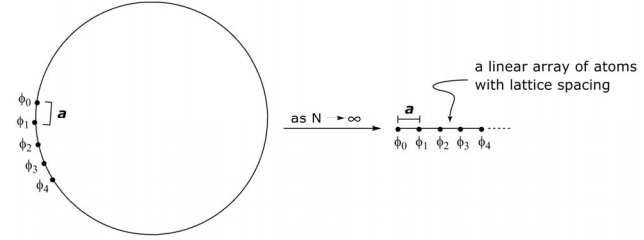

At very large N, as the circumference of the circle approaches ∞, the cyclic problem converges to a linear one,

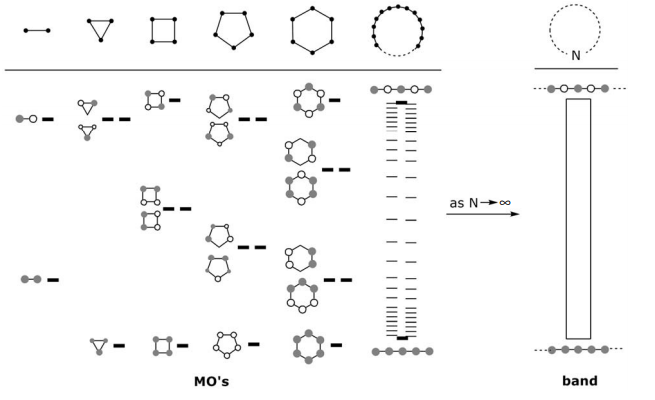

Qualitatively, from a MO energy level perspective,

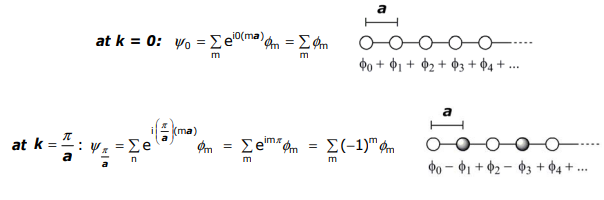

More quantitatively, in moving from cyclic to linear systems, instead of describing orbital (atom) positions angularly, the position of an atom is described by ma, where m is the number of the atom in the array and a is the distance between atoms. Thus, the θ of the N-cyclic derivation becomes ma,

A few words about \(k\). It is:

- a measure of the number of nodes

- an index of wavefunction and accordingly symmetry of wavefunction

- a “quantum number” for a given ψk

- a measure of length, related to wavelength λ–1

- from DeBroglie’s relation, λ = (h/p) , therefore k is also a wave vector that measures momentum

Returning to the foregoing discussion, note that k parametrically depends on a. Since a is a lattice parameter of the unit cell, there are as many k’s as there are unit cells in the crystal. In the linear case, the unit cell is the distance between adjacent atoms: there are n atoms ∴ n unit cells or in other terms – there are as many k’s as atoms in the 1-D chain.

Let’s determine the energy values of limits, k = 0 and k = (π/a) :

The energies for these band structures at the limits of k are:

\[ E_{0} = \alpha + 2\beta \cos(0)a = \alpha + 2\beta \]

\[ E_{ \dfrac{ \pi }{a}} = \alpha + 2\beta \cos( \dfrac{ \pi }{a} )a = \alpha - 2\beta \]

Note that k is quantized; so there are a finite number of values between α+2β and α–2β but for a very large number (~1023 atoms) between the limits of k. Thus, the energy is a continuous and smoothly varying function between these limits.

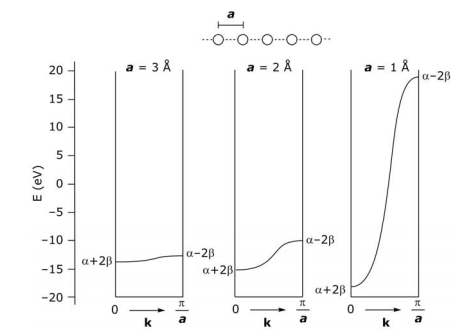

The range - π/a ≤ k ≤ π/a or |k| ≤ π/a is unique because the function repeats itself a a a outside these limits. This unique range of k values is called the Brillouin zone. The first Brillouin zone is plotted above from 0 to π/a (symmetric reflection from − π/a to 0).

With a given number of e– s in the solid, the levels will be filled to a certain energy called the Fermi level, which corresponds to a certain value of k (= kF). In the k above example, there are more electrons than there are orbitals, so kF > k/2a. If each atomic orbital contributed 1e– to the system, then EF would occur for kF = π/2a.

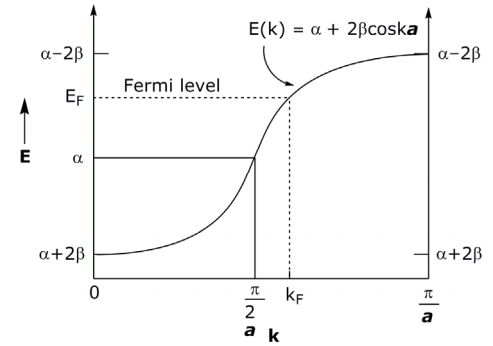

The symmetry of the individual atomic orbitals determines much about band structure. Consider p-orbitals overlapping in a linear array (vs the 1s orbitals of the above treatment). Analyzing limiting forms:

The energy band is opposite of that for the sσ orbital LCAO because the (+) LCAO for a pσ orbital is antibonding.

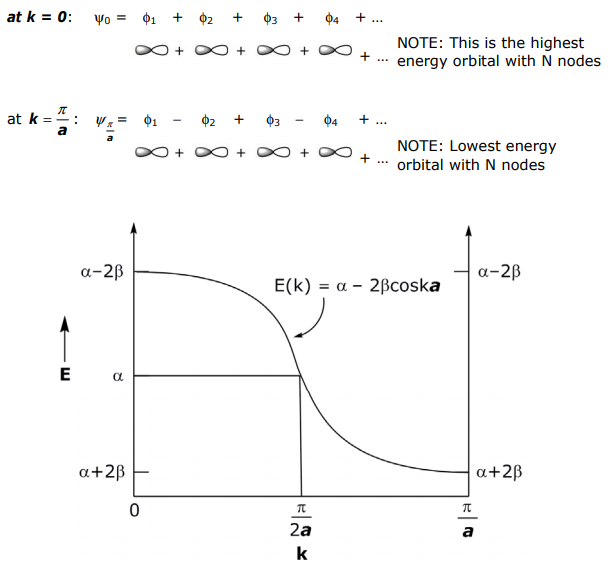

Thus, molecules are easily related to solids via Hückel theory. Not surprisingly, there is a language of chemistry describing the electronic structure of molecules that is related to the language of physics describing the electronic structure of solids. Below are some of the terms that chemists and physicists use to describe similar phenomena in molecules and solids:

Band Width or Dispersion

What determines the width or dispersion of a band? As for the HOMO-LUMO gap in a molecule, the overlap of neighboring orbitals determines the energy dispersion of a band – the greater the overlap, the greater the dispersion. Note how the band dispersion of a linear chain of H atoms varies as the 1s orbitals of the H atoms are spaced 1, 2, 3 Å apart (E of an isolated H atom is –13.6 eV):

Density of States

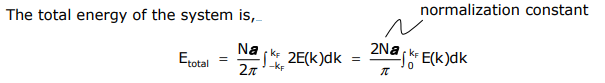

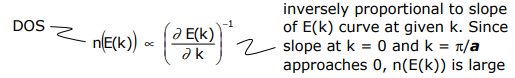

or in other words, it is the area under the curve to kF. Another useful quantity is the number of orbitals between E(k) + dE(k), called the density of states (DOS). For a 1-D system,

A plot of the above equations is,

In the above DOS diagram, no energy gap separates the filled and empty bands, i.e. there is a continuous density of states – this property is characteristic of a metal. If an energy gap between filled and empty orbitals is present and it can be thermally surmounted, then it is semiconductor; an energy gap that cannot be surmounted is an insulator.

A 1-D Example

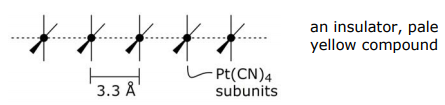

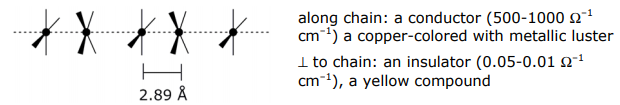

Arguably the best known 1-D system in inorganic chemistry is K2Pt(CN)4 and its partially oxidized compound (e.g. K2Pt(CN)4Br0.3).

Normal platinocyanide, K2Pt(CN)4:

Partially oxidized platinocyanide, K2Pt(CN)4Br0.3•3H2O:

Note: d(Pt-Pt) = 2.78 Å in Pt metal

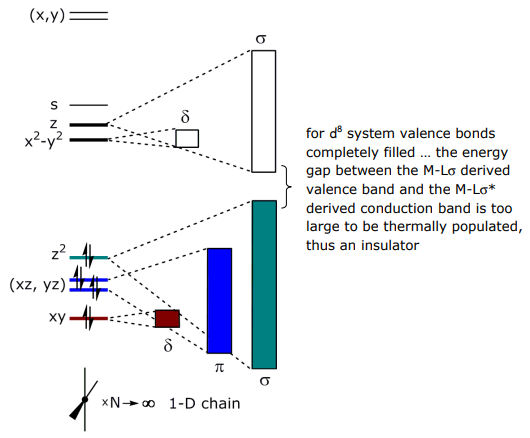

To explain these disparate properties of the 1-D compounds, consider the molecular subunit Pt(CN)42-:

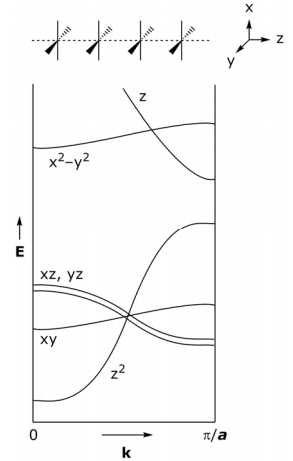

The dispersion of the bands is due to the different overlaps of the dσ, dπ and dδ orbitals.

Band structure (or first Brillouin zones) derived from the frontier MO’s is:

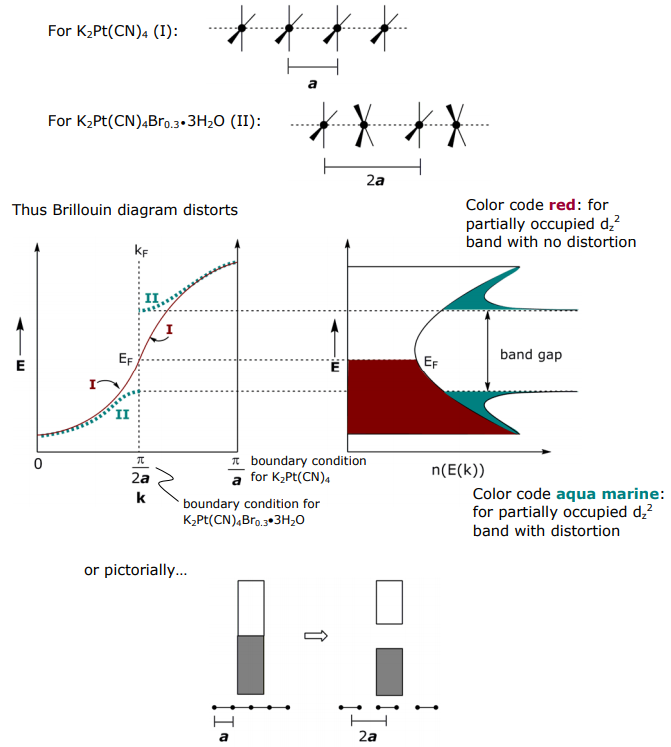

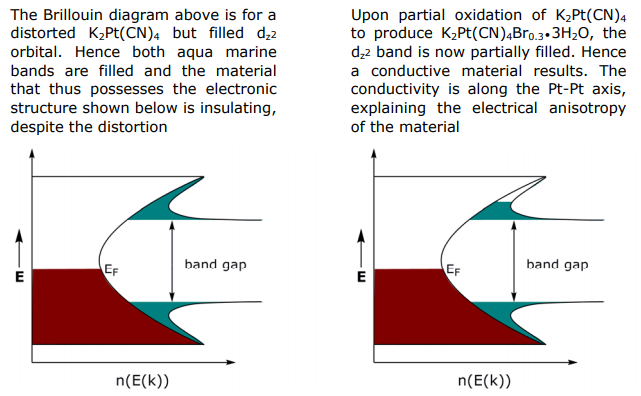

For partially oxidized system, the σ bond derived from dz2 should be partially filled and thus metallic, but it is not, partially oxidized K2Pt(CN)4Brx is a semiconductor. To explain this anomaly, consider how the band structure is perturbed upon partial oxidation:

Isolating on the dz2 band in K2Pt(CN)4, the Pt atoms are evenly spaced with lattice dimension a (I). Upon oxidation, the Pt chain can distort to give a lattice dimension 2a (II). In the case of the K2Pt(CN)4Br0.3•3H2O the distortion is a rotation of Pt subunits and formation of dimers within chain, thus the unit cell dimension is pinned to every other Pt atom.