6.2: Avogadro and Moles, Periodic Table, Isotopes, and Combustion

- Page ID

- 408808

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Avogadro and moles

When balancing a reaction or determining its yield, it was really important to keep track of the number of each kind of atom before and after the reaction. Atoms can be difficult to account for in real life due to their minuscule size. Instead, we usually keep track in moles : a mole consists of Avogadro's number of atoms (or molecules), or \(6.022 \times 10^{23}\) atoms or molecules per mole.

Critically, we can convert from moles to a value that is easy to measure in a lab: mass. The molar mass of a a substance is defined to be the number of grams in one mole of that substance. The molar mass of a single element is also called the atomic mass; the molar mass of a compound can be obtained by summing the molar mass of the constituent elements.

Example: How many moles of nickel are in \(102 \mathrm{~g}\) of nickel? How many moles of \(\mathrm{H}_2 \mathrm{O}\) are in \(50 \mathrm{~g}\) of water?

\begin{gathered}

102 \mathrm{~g} \mathrm{Ni} \times \dfrac{1 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{Ni}}{58.69 \mathrm{~g} \mathrm{Ni}}=1.74 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{Ni} \\

50 \mathrm{~g} \mathrm{H}_2 \mathrm{O} \times \dfrac{1 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{H}_2 \mathrm{O}}{(15.999+2 \times 1.0107) \mathrm{g} \mathrm{H}_2 \mathrm{O}}=2.77 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{H}_2 \mathrm{O}

\end{gathered}

Periodic table

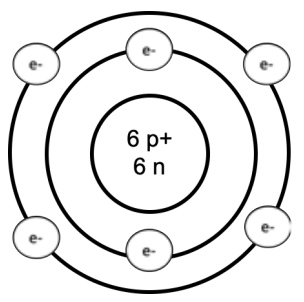

The periodic table is our key to solving problems! It contains a wealth of information that we can use to understand and calculate the properties of materials. The elements are organized by the number of protons: the rows are called periods, and the columns are called groups. Atoms are made up of positively charged protons, neutral neutrons, and negatively charged electrons. Protons and neutrons live at the center of the atom: together, these are the main source of mass. Electrons orbit around the protons and neutrons (more on this later). An example Bohr model of carbon is shown here:

We can read off many properties of atoms from the periodic table: An atom has the same number of protons

and electrons. The atomic mass is the sum of the number of protons and neutrons: it is the average mass of one atom of each element. The units of atomic mass are AMU (atomic mass units, \(=1 / 12\) the mass of a carbon-12 isotope), or equivalently (due to a convenient convention), the number of grams in a mole of a substance.

Isotopes

You may have noticed that the atomic masses on the periodic table aren't integers, even though the number of protons \(+\) neutrons must be an integer. The number represented as atomic mass is really the average atomic mass, where a weighted average is taken over the possible isotopes of an atom. An isotope is an atom that has a few extra (or missing) neutrons, and therefore a different atomic mass. Isotopes are usually written like this:

\({ }_Z^A X\)

Here, \(\mathrm{X}\) is the element symbol, \(\mathrm{Z}\) is the atomic number, and \(\mathrm{A}\) is the atomic mass. The number of neutrons in the isotope is just

\(\# \text { neutrons }=A-Z\)

Example: Complete the following table:

| Isotope | Abundance | Atomic mass (amu) |

|---|---|---|

| \({ }^{28} \mathrm{Si}\) | \(92.18\%\) | \(28\) |

| \({ }^{29} \mathrm{Si}\) | ? | \(29\) |

| \({ }^x \mathrm{Si}\) | \(3.12\%\) | ? |

From the periodic table, the average atomic mass of silicon is \(28.0855\) amu. First, we can solve for the percentage of \({ }^{29} \mathrm{Si}\) by using the fact that the total abundance must sum to \(100 \%\):

\begin{gathered}

100 \%=92.18 \%+3.12 \%+y \\

y=4.71 \%

\end{gathered}

Then, we can use a weighted average to calculate the atomic mass and determine what the third isotope is:

\begin{gathered}

28.0855=0.9218 \times(28 a m u)+0.0471 \times(29 a m u)+0.0312 x \\

x=30

\end{gathered}

Combustion

A combustion reaction occurs when a substance reacts with oxygen gas, producing light and heat.

Example: If you put \(400 \mathrm{~g}\) of sugar (glucose) into a \(1 \mathrm{~m}^3\) box, light it on fire, and quickly seal the box, would there be enough oxygen to completely combust the sugar? Write a balanced reaction; determine the limiting reagent and yield.

Density of air: \(1.225 \mathrm{~g} / \mathrm{L}=1.225 \mathrm{~kg} / \mathrm{m}^3\)

Oxygen weight percentage in air: \(23.2 \%\)

Chemical formula of glucose: \(\mathrm{C}_6 \mathrm{H}_{12} \mathrm{O}_6\)

We can try to match the number of moles in the glucose by adjusting the coefficients on the right side. This gives the right number of \(\mathrm{C}\) and \(\mathrm{H}\). Finally, we can adjust the coefficient on the oxygen to get a balanced reaction:

\(\mathrm{C}_6\mathrm{H}_{12}\mathrm{O}_6 + 6\mathrm{O}_2 \rightarrow 6\mathrm{CO}_2 + 6\mathrm{H}_2\mathrm{O}\)

To determine the limiting reagent, we need to figure out how many moles of each reactant we have:

400 g glucose \(\times \dfrac{1 \mathrm{~mol} \text { glucose }}{(6 \times 12.0107+12 \times 1.01+6 \times 15.999) \text { g glucose }}=2.22 \mathrm{~mol}\) glucose

Next, we need to determine how much oxygen is in the box:

\(1 m^3 \text { air } \times \dfrac{1.225 \mathrm{~kg} \text { air }}{1 m^3 \text { air }} \times \dfrac{1000 g}{k g} \times 0.232 \times \dfrac{1 \text { mol oxygen }}{2 \times 15.999 \text { g oxygen }}=8.88 \text { mol oxygen }\)

where the multiplication by \(0.232\) to account for the fact that air is \(23.2 \%\) oxygen.

We need 6 times as much oxygen as glucose to fully react, and \(6.66 / 2.22 \leq 6\), so oxygen is the limiting reagent. We can use the limiting reagent to calculate the yield:

\(8.88 \mathrm{~g} \mathrm{O}_2 \times \dfrac{1 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{H}_2 \mathrm{O}}{1 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{O}_2} \times \dfrac{(2 \times 1.01+15.999) \mathrm{g} \mathrm{H}_2 \mathrm{O}}{1 \mathrm{~mol} \mathrm{H}_2 \mathrm{O}}=158.8 \mathrm{~g} \mathrm{H}_2 \mathrm{O}\)