9.5: Hydrogen Peroxide Providing a Lift for 007

- Page ID

- 212669

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)In the pre-credit sequence of the 1965 film Thunderball, James Bond 007 (played by Sean Connery) uses a Jetpack to escape from two gunmen after killing Jacques Bouvar, SPECTRE Agent No. 6 (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). The Jetpack was also used in the Thunderball posters, being the "Look Up" part of the "Look Up! Look Down! Look Out!" tagline (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). The Jetpack returned in 2002 in Die Another Day (in which Pierce Brosnan played Bond) in the Q scene that showcased many other classic gadgets from previous Bond films.

The Jetpack was actually a real fully functional device: the Bell Rocket Belt. It was designed for use in the US Army, but was rejected because of its short flying time of 21-22 seconds. Powered by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), it could fly about 250 m and reach a maximum altitude of 18 m, going 55 km/h. Despite its impracticality in the real world, the Jetpack made a spectacular debut in Thunderball. Although Sean Connery is seen in close-up during the takeoff and landings (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)), the main flight was actually piloted by Gordon Yeager (Fugre 4) and Bill Suitor (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)).

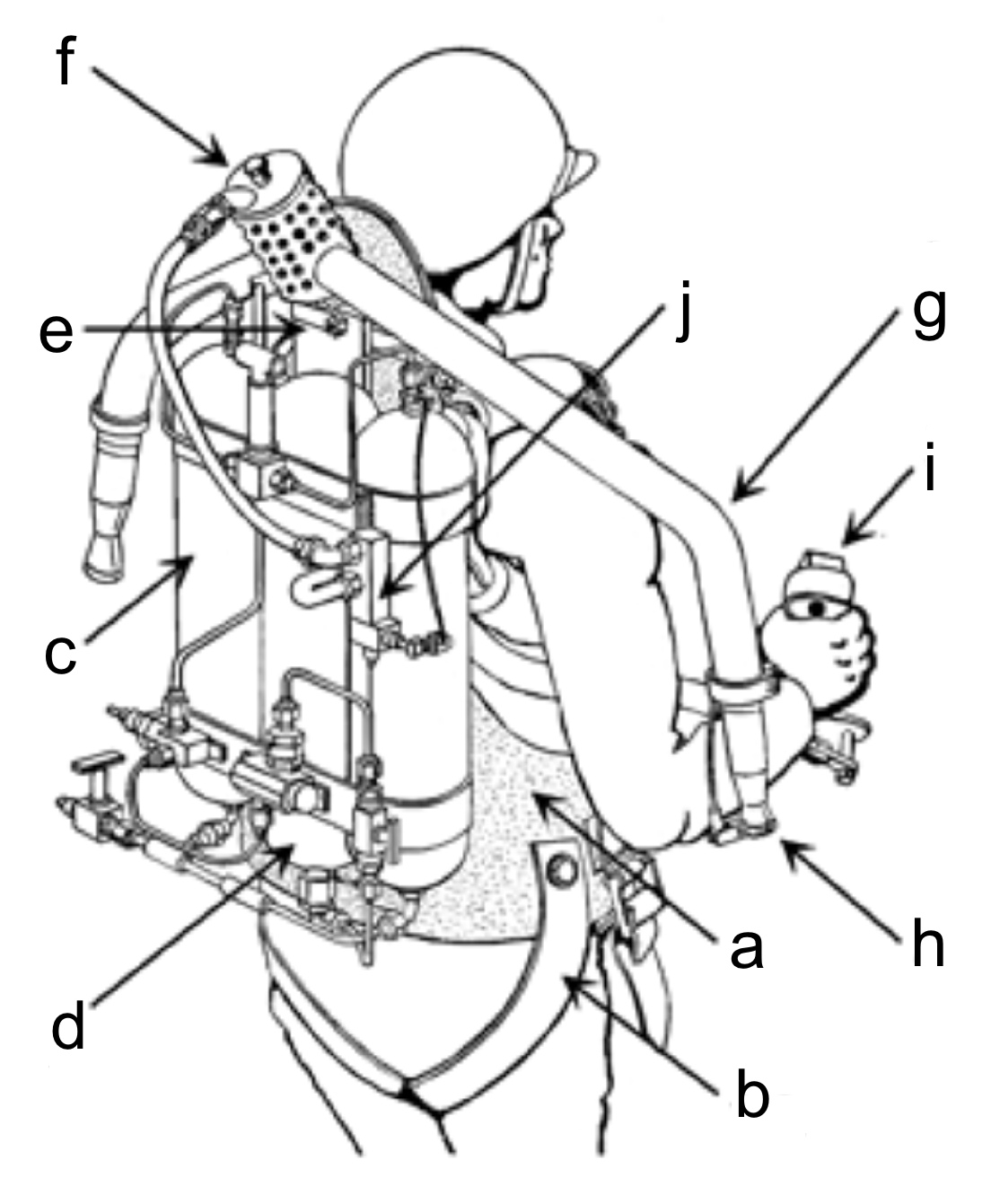

The Bell Rocket Belt is a low-power rocket propulsion device that allows an individual to safely travel or leap over small distances. All subsequent rocket packs were based on the construction design, developed in 1960-1969 by Wendell Moore. Moore's pack has two major parts:

- Rigid glass-plastic corset (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)a), strapped to the pilot (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)b). The corset has a tubular metallic frame on the back, on which are fixed three gas cylinders: two with liquid hydrogen peroxide (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)c), and one with compressed nitrogen (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)d). When the pilot is on the ground, the corset distributes the weight of the pack to the pilot's back.

- The rocket engine, able to move on a ball and socket joint (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)e) in the upper part of the corset. The rocket engine consists of a gas generator (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)f) and two pipes (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)g) rigidly connected with it, which end with jet nozzles with controlled tips (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)h). The engine is rigidly connected to two levers, which are passed under the pilot's hands. Using these levers the pilot inclines the engine forward or back and to the sides. On the right lever is the thrust control turning handle (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)i), connected with a cable to the regulator valve (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)j) to supply fuel to the engine. On the left lever is the steering handle, which controlled the tips of jet nozzles.

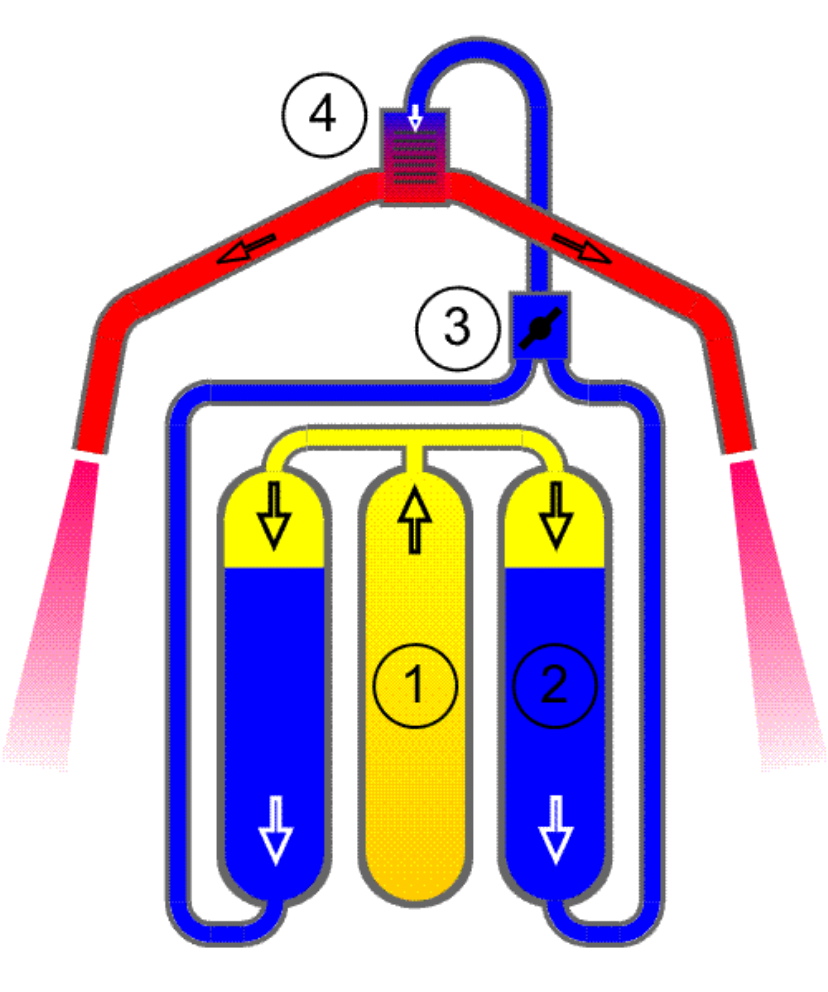

The operating principle of the Jetpack is shown in Figure. The hydrogen peroxide cylinders and compressed nitrogen cylinder are each at a pressure of ca. 40 atm or 4 MPa). To operate the pilot turns the engine thrust control handle, and opens the regulator valve (3 in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)). Compressed nitrogen (1 in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)) displaces liquid hydrogen peroxide (2 in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)), which enters the gas generator (4 in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)). In the gas generator, the hydrogen peroxide contacts the catalyst and is decomposed. The catalyst consists of thin silver plates, covered with a layer of samarium nitrate. The resulting hot high-pressure mixture of steam and gas enters two pipes, which emerge from the gas generator. These pipes are covered with a layer of heat insulator to reduce loss of heat. The hot gas enters the jet nozzles, where first they are accelerated, and then expand, acquiring supersonic speed and creating reactive thrust. The whole construction is simple and reliable; the rocket engine has no moving parts. The pack has two levers, rigidly connected to the engine installation. Pressing on these levers, the pilot deflects the nozzles back, and the pack flies forward. Accordingly, raising this lever makes the pack move back. It is possible to lean the engine installation to the sides (because of the ball and socket joint) to fly sideways.